Anachronism

_-_The_Last_Supper_(1495-1498).jpg)

An anachronism (from the Greek ἀνά ana, "against" and χρόνος khronos, "time") is a chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of persons, events, objects, or customs from different periods of time. The most common type of anachronism is an object misplaced in time, but it may be a verbal expression, a technology, a philosophical idea, a musical style, a material, a plant or animal, a custom or anything else associated with a particular period in time so that it is incorrect to place it outside its proper temporal domain.

An anachronism may be either intentional or unintentional. Intentional anachronisms may be introduced into a literary or artistic work to help a contemporary audience engage more readily with a historical period. Anachronism can also be used for purposes of rhetoric, comedy, or shock. Unintentional anachronisms may occur when a writer, artist, or performer is unaware of differences in technology, language, customs, attitudes, or fashions between different historical eras.

Types

Parachronism

A parachronism (from the Greek παρά, "on the side", and χρόνος, "time") is anything that appears in a time period in which it is not normally found (though not sufficiently out of place as to be impossible).

This may be an object, an idiomatic expression, a technology, a philosophical idea, a musical style, a material, a custom, or anything else sufficiently closely bound to a particular time period as to seem strange when encountered in a later era. They may be objects or ideas which were once common, but are now considered rare or inappropriate. They can take the form of obsolete technology or outdated fashion.

Examples of parachronisms could include a suburban housewife in the United States around 1960 using a washboard for laundry (well after washing machines had become the norm); or a teenager from that time period being an avid fan of ragtime music. Often, a parachronism is identified when a work based on a particular era's state of knowledge is read within the context of a later era—with a different state of knowledge. Many scientific works that rely on theories that have later been discredited have become anachronistic with the removal of those underpinnings, and works of speculative fiction often find their speculations outstripped by real-world technological developments or scientific discoveries.

Prochronism

A prochronism (from the Greek πρό, "before", and χρόνος, "time") is an impossible anachronism which occurs when an object or idea has not yet been invented when the situation takes place, and therefore could not have possibly existed at the time (e.g. The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci at the top of this page). A prochronism may be an object not yet developed, a verbal expression that had not yet been coined, a philosophy not yet formulated, a breed of animal not yet evolved (or perhaps engineered), or use of a technology that had not yet been created.

Behavioral and cultural anachronism

The intentional use of older, often obsolete cultural artifacts may be regarded as anachronistic. For example, it could be considered anachronistic for a modern-day person to wear a top hat, write with a quill, or carry on a conversation in Latin. Such choices may reflect an eccentricity or an aesthetic preference.

Politically motivated anachronism

Some writings and works of art promoting a political, nationalist or revolutionary cause use anachronism to depict an institution or custom as being more ancient than it actually is. For example, the 19th-century Romanian painter Constantin Lecca depicts the peace agreement between Ioan Bogdan Voievod and Radu Voievod—two leaders in Romania's 16th-century history—with the flags of Moldavia (blue-red) and of Wallachia (yellow-blue) seen in the background. These flags date only from the 1830s. Here anachronism promotes legitimacy for the unification of Moldavia and Wallachia into the Kingdom of Romania at the time the painting was made.

Art and literature

Anachronism is used especially in works of imagination that rest on a historical basis. Anachronisms may be introduced in many ways: for example, in the disregard of the different modes of life and thought that characterize different periods, or in ignorance of the progress of the arts and sciences and other facts of history. They vary from glaring inconsistencies to scarcely perceptible misrepresentation. It is only since the close of the 18th century that this kind of deviation from historical reality has jarred on a general audience. Sir Walter Scott justified the use of anachronism in historical literature: "It is necessary, for exciting interest of any kind, that the subject assumed should be, as it were, translated into the manners as well as the language of the age we live in."[2] However, as fashions move on, such attempts to use anachronisms to engage an audience may have quite the reverse effect, as the details in question are increasingly recognized as belonging neither to the historical era being represented, nor to the present, but to the intervening period in which the artwork was created. "Nothing becomes obsolete like a period vision of an older period", writes Anthony Grafton; "Hearing a mother in a historical movie of the 1940s call out 'Ludwig! Ludwig van Beethoven! Come in and practice your piano now!' we are jerked from our suspension of disbelief by what was intended as a means of reinforcing it, and plunged directly into the American bourgeois world of the filmmaker."[3]

Anachronism can also be an aesthetic choice.[4] Anachronisms abound in the works of Raphael[5] and Shakespeare,[6] as well as in those of less celebrated painters and playwrights of earlier times. Anachronisms can exist in ancient texts. Carol Meyers says that these anachronisms can be used to better understand the stories by asking what the anachronism represents.[7] Repeated anachronisms and historical errors can become an accepted part of popular culture, such as Roman legionaries that wear leather armor.[8]

Comical anachronism

Comedy fiction set in the past may use anachronism for humorous effect. Comedic anachronism can be used to make serious points about both historical and modern society, such as drawing parallels to political or social conventions.[9]

Future anachronism

Even with careful research, science fiction writers risk anachronism as their works age because they cannot predict all political and technological change.[10]

For example, many books and films nominally set in the mid-21st century or later refer to the Soviet Union, which ceased to exist in 1991, or to Saint Petersburg in Russia as Leningrad, and many works set in time periods long after 1990 refer to divided Germany and divided Berlin. Star Trek, which has a history of predicting technology, has suffered from future anachronisms; instead of "retconning" these errors, the 2009 film retained them for consistency with older franchises.[11] Buildings or natural features, such as the World Trade Center in New York City, can become out of place once they disappear.[12]

Language anachronism

Language anachronisms in novels and films are quite common, both intentional and unintentional.[13] Intentional anachronisms inform the audience more readily about a film set in the past. In this regard, language and pronunciation change so fast that most modern people (even many scholars) would find it difficult, or even impossible, to understand a film with dialogue in 17th-century English; thus, we willingly accept characters speaking an updated language, and modern slang and figures of speech are often used in these films.[14]

Subconscious anachronism

Unintentional anachronisms may occur even in what are intended as wholly objective and accurate records of historic artifacts, because the recorder's perspective is conditioned by the assumptions and practices of his or her own times (a form of cultural bias). One example is the attribution of historically inaccurate beards to various medieval tomb effigies and figures in stained glass in records made by English antiquaries of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Working in an age in which beards were in fashion and widespread, the antiquaries seem to have subconsciously projected the fashion back into an era in which it was rare.[15]

Time travel

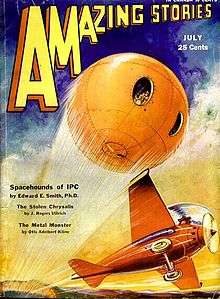

The extensive science fiction subgenre depicting time travel in effect consists of deliberate, consciously created anachronisms, letting people of one time meet and interact with those of another time. Covers of time-travel books often depict deliberate anachronisms of this kind.

In academia

In historical writing, the most common type of anachronism is the adoption of the political, social or cultural concerns and assumptions of one era to interpret or evaluate the events and actions of another. The anachronistic application of present-day perspectives to comment on the historical past is sometimes described as presentism. Empiricist historians, working in the traditions established by Leopold von Ranke in the 19th century, regard this as a great error, and a trap to be avoided.[16] Arthur Marwick has argued that "a grasp of the fact that past societies are very different from our own, and ... very difficult to get to know" is an essential and fundamental skill of the professional historian; and that "anachronism is still one of the most obvious faults when the unqualified (those expert in other disciplines, perhaps) attempt to do history".[17] Anachronism in academic writing is considered at best embarrassing, as in early-20th-century scholarship's use of Translatio imperii, first formulated in the 12th century, to interpret 10th-century literature. Genuine errors will usually be acknowledged in a subsequent erratum.

The use of anachronism in a rhetorical or hyperbolic sense is more complex. To refer to the Holy Roman Empire as the First Reich, for example, is technically inaccurate but may be a useful comparative exercise; the application of theory to works which predate Marxist, Feminist or Freudian subjectivities is considered an essential part of theoretical practice. In most cases, however, the practitioner will acknowledge or justify the use or context.

Detection of anachronism

The ability to identify anachronisms may be employed as a critical and forensic tool to demonstrate the fraudulence of a document or artifact purporting to be from an earlier time. Anthony Grafton discusses, for example, the work of the 3rd-century philosopher Porphyry, of Isaac Casaubon (1559–1614), and of Richard Reitzenstein (1861–1931), all of whom succeeded in exposing literary forgeries and plagiarisms, such as those included in the "Hermetic Corpus", through – among other techniques – the recognition of anachronisms.[18] The detection of anachronisms is an important element within the scholarly discipline of diplomatics, the critical analysis of the forms of documents, developed by the Maurist scholar Jean Mabillon (1632–1707) and his successors René-Prosper Tassin (1697–1777) and Charles-François Toustain (1700–1754). The philosopher and reformer Jeremy Bentham wrote at the beginning of the 19th century:

The falsehood of a writing will often be detected, by its making direct mention of, or allusions more or less indirect to, some fact posterior to the date which it bears. ... The mention of posterior facts; – first indication of forgery.

In a living language there are always variations in words, in the meaning of words, in the construction of phrases, in the manner of spelling, which may detect the age of a writing, and lead to legitimate suspicions of forgery. ... The use of words not used till after the date of the writing; – second indication of forgery.[19]

The exposure by Lorenzo Valla in 1440 of the so-called Donation of Constantine, a decree purportedly issued by the Emperor Constantine the Great in either 315 or 317 AD, as a later forgery, depended to a considerable degree on the identification of anachronisms, such as references to the city of Constantinople (a name not in fact bestowed until 330 AD). A large number of apparent anachronisms in the Book of Mormon have served to convince critics that the book was written in the 19th century, and not, as its adherents claim, in pre-Columbian America. The use of 19th- and 20th-century anti-semitic terminology demonstrates that the purported "Franklin Prophecy" (attributed to Benjamin Franklin, who died in 1790) is a forgery.[20] The ""William Lynch speech", an address, supposedly delivered in 1712, on the control of slaves in Virginia, is now considered to be a 20th-century forgery, partly on account of its use of anachronistic terms such as "program" and "refueling".[21]

See also

- Anatopism

- Invented traditions

- Presentism

- Retrofuturism

- Society for Creative Anachronism

- Steampunk

- Whig history

- 1812 Overture#Anachronism of nationalist motifs

References

- ↑ McCouat, Philip (2014). "On the trail of the last supper". Journal of Art in Society. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ↑ Scott, Walter (1820). Ivanhoe; a Romance. 1. Edinburgh. p. xvii.

- ↑ Grafton 1990, p. 67.

- ↑ Potthast, Jane (2013-09-18). "For Infidelity: Reconsidering Aesthetic Anachronism". PopMatters. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ von Wolzogen, Alfred Freiherr (1866). Raphael Santi: His Life and His Works. Smith, Elder & Co. p. 232.

- ↑ Martindale, Michelle (2005). Shakespeare and the Uses of Antiquity: An Introductory Essay. Routledge. pp. 121–125. ISBN 9781134848508.

- ↑ Montagne, Renee (2014-02-14). "Archaeology Find: Camels In 'Bible' Are Literary Anachronisms". NPR. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- ↑ Cole, Tom (2011-03-31). "Time meddlers: anachronisms in print and on film". Radio Times. Retrieved 2014-07-31.

- ↑ van Riper, A. Bowdoin (2013-09-26). "Hollywood, History, and the Art of the Big Anachronism". PopMatters. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Athans, Philip; Salvatore, R. A. (2010). The Guide to Writing Fantasy and Science Fiction. Adams Media. pp. 167–170. ISBN 9781440507298.

- ↑ Glaskowsky, Peter (2009-05-08). "Living the Star Trek life". CNET. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Hornaday, Ann (2002-12-06). "'Empire': Gangster Tale Sleeps With the Fishes". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Nunberg, Geoff (2013-02-26). "Historical Vocab: When We Get It Wrong, Does It Matter?". NPR. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Safire, William (2000-03-26). "The Way We Live Now: 3-26-00: On Language; Anachronism". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-07-31.

- ↑ Harris, Oliver D. (2013). "Beards: true and false". Church Monuments. 28: 124–32.

- ↑ Davies, Stephen (2003). Empiricism and History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 29.

- ↑ Marwick, Arthur (2001). The New Nature of History: knowledge, evidence, language. Basingstoke: Palgrave. p. 63. ISBN 0-333-96447-0.

- ↑ Grafton 1990, pp. 75–98.

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy (1825). Dumont, Étienne, ed. A Treatise on Judicial Evidence. London: Baldwin, Cradock and Joy. p. 140.

- ↑ "Anti-Semitic Myth: The Franklin "Prophecy"". Adl.org. Retrieved 2013-02-01.

- ↑ Cobb, W. Jelani (2004). "Is Willie Lynch's Letter Real?". Retrieved 27 July 2016.

Bibliography

- Grafton, Anthony (1990). Forgers and Critics: creativity and duplicity in Western scholarship. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691055440.

External links

-

The dictionary definition of anachronism at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of anachronism at Wiktionary -

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Anachronism". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Anachronism". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.