Amethyst

| Amethyst | |

|---|---|

|

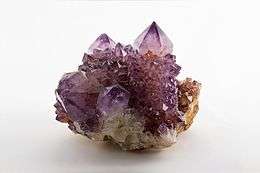

Amethyst cluster from Magaliesburg, South Africa. | |

| General | |

| Category | oxide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2) |

| Crystal system | Trigonal |

| Crystal class | Trapezohedral (32) |

| Identification | |

| Color | Purple, violet |

| Crystal habit | 6-sided prism ending in 6-sided pyramid (typical) |

| Twinning | Dauphine law, Brazil law, and Japan law |

| Cleavage | None |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7–lower in impure varieties |

| Luster | Vitreous/glassy |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent |

| Specific gravity | 2.65 constant; variable in impure varieties |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+) |

| Refractive index |

nω = 1.543–1.553 nε = 1.552–1.554 |

| Birefringence | +0.009 (B-G interval) |

| Pleochroism | None |

| Melting point | 1650±75 °C |

| Solubility | insoluble in common solvents |

| Other characteristics | Piezoelectric |

Amethyst is a violet variety of quartz often used in jewelry.

The name comes from the Koine Greek ἀμέθυστος amethystos from ἀ- a-, "not" and μεθύσκω methysko / μεθύω methyo, "intoxicate", a reference to the belief that the stone protected its owner from drunkenness.[1] The ancient Greeks wore amethyst and made drinking vessels decorated with it in the belief that it would prevent intoxication.

It is one of several forms of quartz. Amethyst is a semiprecious stone and is the traditional birthstone for February.

Structure

Amethyst is a purple variety of quartz (SiO2) and owes its violet color to irradiation, iron impurities (in some cases in conjunction with transition element impurities), and the presence of trace elements, which result in complex crystal lattice substitutions.[2][3][4] The hardness of the mineral is the same as quartz, thus it is suitable for use in jewelry.

Hue and tone

Amethyst occurs in primary hues from a light pinkish violet to a deep purple. Amethyst may exhibit one or both secondary hues, red and blue. The best varieties of amethyst can be found in Siberia, Sri Lanka, Brazil and the far East. The ideal grade is called "Deep Siberian" and has a primary purple hue of around 75–80%, with 15–20% blue and (depending on the light source) red secondary hues.[5] Green quartz is sometimes incorrectly called green amethyst, which is a misnomer and not an appropriate name for the material, the proper terminology being prasiolite. Other names for green quartz are vermarine or lime citrine.

Of very variable intensity, the color of amethyst is often laid out in stripes parallel to the final faces of the crystal. One aspect in the art of lapidary involves correctly cutting the stone to place the color in a way that makes the tone of the finished gem homogeneous. Often, the fact that sometimes only a thin surface layer of violet color is present in the stone or that the color is not homogeneous makes for a difficult cutting.

The color of amethyst has been demonstrated to result from substitution by irradiation of trivalent iron (Fe3+) for silicon in the structure,[4][6] in the presence of trace elements of large ionic radius,[3] and, to a certain extent, the amethyst color can naturally result from displacement of transition elements even if the iron concentration is low. Natural amethyst is dichroic in reddish violet and bluish violet,[4] but when heated, turns yellow-orange, yellow-brown, or dark brownish and may resemble citrine,[7] but loses its dichroism, unlike genuine citrine. When partially heated, amethyst can result in ametrine.

Amethyst can fade in tone if overexposed to light sources and can be artificially darkened with adequate irradiation.[4]

History

Amethyst was used as a gemstone by the ancient Egyptians and was largely employed in antiquity for intaglio engraved gems.[8]

The Greeks believed amethyst gems could prevent intoxication,[9] while medieval European soldiers wore amethyst amulets as protection in battle in the belief that amethysts heal people and keep them cool-headed.[10] Beads of amethyst were found in Anglo-Saxon graves in England.[11] Anglican bishops wear an episcopal ring often set with an amethyst, an allusion to the description of the Apostles as "not drunk" at Pentecost in Acts 2:15.[12]

A large geode, or "amethyst-grotto", from near Santa Cruz in southern Brazil was presented at a 1902 exhibition in Düsseldorf, Germany.[1]

In the 19th century, the color of amethyst was attributed to the presence of manganese. However, since it can be greatly altered and even discharged by heat, the color was believed by some authorities to be from an organic source. Ferric thiocyanate has been suggested, and sulfur was said to have been detected in the mineral.[1]

Synthetic amethyst

Synthetic (laboratory-grown) amethyst is produced by a synthesis method called hydrothermal growth, which grows the crystals inside a high-pressure autoclave.

Synthetic amethyst is made to imitate the best quality amethyst. Its chemical and physical properties are the same to that of natural amethyst and it can not be differentiated with absolute certainty without advanced gemmological testing (which is often cost-prohibitive). There is one test based on "Brazil law twinning" (a form of quartz twinning where right and left hand quartz structures are combined in a single crystal[13]) which can be used to identify synthetic amethyst rather easily. It is possible to synthesize twinned amethyst, but this type is not available in large quantities in the market.[5]

Single-crystal quartz is very desirable in the industry, particularly for keeping the regular vibrations necessary for quartz movements in watches and clocks, which is where a lot of synthetic quartz is used.

Treated amethyst is produced by gamma ray, X-ray or electron beam irradiation of clear quartz (rock crystal) which has been first doped with ferric impurities. On exposure to heat, the irradiation effects can be partially cancelled and amethyst generally becomes yellow or even green, and much of the citrine, cairngorm, or yellow quartz of jewelry is said to be merely "burnt amethyst".[1][14]

Cultural history

Ancient Greece

The Greek word "amethystos" may be translated as "not drunken", from Greek a-, "not" + methustos, "intoxicated".[15] Amethyst was considered to be a strong antidote against drunkenness,[16] which is why wine goblets were often carved from it.[17] In his poem "L'Amethyste, ou les Amours de Bacchus et d'Amethyste" (Amethyst or the loves of Bacchus and Amethyste), the French poet Remy Belleau (1528–1577) invented a myth in which Bacchus, the god of intoxication, of wine, and grapes was pursuing a maiden named Amethyste, who refused his affections. Amethyste prayed to the gods to remain chaste, a prayer which the chaste goddess Diana answered, transforming her into a white stone. Humbled by Amethyste's desire to remain chaste, Bacchus poured wine over the stone as an offering, dyeing the crystals purple.[18][19]

Variations of the story include that Dionysus had been insulted by a mortal and swore to slay the next mortal who crossed his path, creating fierce tigers to carry out his wrath. The mortal turned out to be a beautiful young woman, Amethystos, who was on her way to pay tribute to Artemis. Her life was spared by Artemis, who transformed the maiden into a statue of pure crystalline quartz to protect her from the brutal claws. Dionysus wept tears of wine in remorse for his action at the sight of the beautiful statue. The god's tears then stained the quartz purple.[20]

This myth and its variations are not found in classical sources. However, the titan Rhea does present Dionysus with an amethyst stone to preserve the wine-drinker's sanity in historical text.[21]

Other cultural associations

Tibetans consider amethyst sacred to the Buddha and make prayer beads from it.[22] Amethyst is considered the birthstone of February.[23] In the Middle Ages, it was considered a symbol of royalty and used to decorate English regalia.[23] In the Old World, amethyst was considered one of the Cardinal gems, in that it was one of the five gemstones considered precious above all others, until large deposits were found in Brazil.

Geographic distribution

Amethyst is produced in abundance from the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil where it occurs in large geodes within volcanic rocks. Many of the hollow agates of southwestern Brazil and Uruguay contain a crop of amethyst crystals in the interior. Artigas, Uruguay and neighboring Brazilian state Rio Grande do Sul are large world producers exceeding in quantity Minas Gerais, as well as Mato Grosso, Espirito Santo, Bahia, and Ceará states, all amethyst producers of importance in Brazil.

It is also found and mined in South Korea. The largest opencast amethyst vein in the world is in Maissau, Lower Austria. Much fine amethyst comes from Russia, especially from near Mursinka in the Ekaterinburg district, where it occurs in drusy cavities in granitic rocks. Many localities in south India yield amethyst.[1] One of the largest global amethyst producers is Zambia in southern Africa with an annual production of about 1000 tons.

Amethyst occurs at many localities in the United States. Among these may be mentioned: the Mazatzal Mountain region in Gila and Maricopa Counties, Arizona; Red Feather Lakes, near Ft Collins, Colorado; Amethyst Mountain, Texas; Yellowstone National Park; Delaware County, Pennsylvania; Haywood County, North Carolina; Deer Hill and Stow, Maine and in the Lake Superior region of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan.[1] Amethyst is relatively common in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Nova Scotia. The largest amethyst mine in North America is located in Thunder Bay, Ontario.

Amethyst is the official state gemstone of South Carolina. Several South Carolina amethysts are on display at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.[24]

Value

Up until the 18th century, amethyst was included in the cardinal, or most valuable, gemstones (along with diamond, sapphire, ruby, and emerald). However, since the discovery of extensive deposits in locations such as Brazil, it has lost most of its value.

Collectors look for depth of color, possibly with red flashes if cut conventionally.[25] As amethyst is readily available in large structures the value of the gem is not primarily defined by carat weight; this is different to most gemstones where the carat weight exponentially increases the value of the stone. The biggest factor in the value of amethyst is the color displayed.[26]

The highest grade amethyst (called "Deep Russian") is exceptionally rare and therefore, when one is found, its value is dependent on the demand of collectors. It is, however, still orders of magnitude lower than the highest grade sapphires or rubies (padparadscha sapphire or "pigeon's blood" ruby).[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rudler, Frederick William (1911). "Amethyst". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 852.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rudler, Frederick William (1911). "Amethyst". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 852. - ↑ Norman N. Greenwood and Alan Earnshaw (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth–Heinemann. ISBN 0080379419.

- 1 2 Fernando S. Lameiras; Eduardo H. M. Nunes; Wander L. Vasconcelos (2009). "Infrared and Chemical Characterization of Natural Amethysts and Prasiolites Colored by Irradiation". Materials Research. 12 (3): 315–320. doi:10.1590/S1516-14392009000300011.

- 1 2 3 4 Michael O'Donoghue (2006), Gems, Butterworth-Heinemann, 6th ed. ISBN 978-0-7506-5856-0

- 1 2 3 Richard W. Wise (2005), Secrets of the Gem Trade; The Connoisseur's Guide to Precious Gemstones, Brunswick House Press, Lenox, Mass., ISBN 0-9728223-8-0

- ↑ George R. Rossman (1994). "Ch.13. Colored Varieties of the Silica Minerals". In Peter J. Heaney; Charles T. Prewitt; Gerald V. Gibbs. Silica: physical behavior, geochemistry, and materials applications. Reviews in Mineralogy. 29. Mineralogical Society of America. pp. 433–468. ISBN 0-939950-35-9.

- ↑ Amethyst. Mindat.org

- ↑ Augosto Castellani (famous Italian 19th century jeweler) (1871), Gems, Notes and Extracts, p. 34, London, Bell and Daldy, ISBN 1-141-06174-0.

- ↑ Marcell N. Smith (1913), Diamonds, Pearls and Precious Stones Griffith Stillings Press, Boston, Mass., p. 74

- ↑ George Frederick Kunz (1913), Curious Lore of Precious Stones, Lippincott Company, Philadelphia & London, p. 77

- ↑ Michael Lapidge (ed.) (2000), The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 261, ISBN 0631224920.

- ↑ Bays, P. (2012). This Anglican Church of Ours. Woodlake Book. p. 136. ISBN 9781770644397.

- ↑ "Quartz Page Twinning Crystals". quartzpage.de.

- ↑ Michael O'Donoghue (1997). Synthetic, Imitation, and Treated Gemstones. Taylor & Francis. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-7506-3173-0.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "amethyst". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ See, for example:

- The earliest reference to amethyst as a symbol of sobriety is in a poem by Asclepiades of Samos (born ~320 BCE). See: "XXX. Kleopatra's Ring" in: Edward Storer, trans., The Windflowers of Asklepiades and the Poems of Poseidippos (London, England: Egoist Press, 1920), page 14.

- An epigram by "Plato the Younger" also mentions amethyst in connection with drinking: "The stone is an amethyst; but I, the tipler Dionysus, say, "Let it either persuade me to be sober, or let it learn to get drunk." See: George Burges et al., The Greek Anthology, … (London, England: George Bell and Sons, 1881), p. 369.

- Pliny says about amethysts: "The falsehoods of the magicians would persuade us that these stones are preventive of inebriety, and that it is from this that they have derived their name." See: Chapter 40 of Book 37 of Pliny the Elder's The Natural History.

- ↑ Federman, David (2012). Modern Jeweler’s Consumer Guide to Colored Gemstones. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-1-4684-6488-7.

- ↑ The "myth" of Amethyste and Bacchus was invented by the French poet Remy Belleau (1528–1577). See: "L'Amethyste, ou les Amours de Bacchus et d'Amethyste" from Belleau's collection of poems "Les Amours et Nouveaux Eschanges des Pierres Precieuses: Vertus & Proprietez d'icelles" (The loves and new transformations of the precious stones: their virtues and properties), which was published in: Remy Belleau, Les Amours et Nouveaux Eschanges des Pierres Precieuses … (Paris, France: Mamert Patisson, 1576), pp. 4–6.

- ↑ George Frederick Kunz (1913). Curious Lore of Precious Stones. pp. 58–59.

- ↑ The amethyst, Gemstone.org

- ↑ Nonnus, Dionysiaca, 12. 380

- ↑ Tropical Gemstones, by Carol Clark p.52

- 1 2 February Birthstone | Amethyst. Americangemsociety.org (2016-01-12). Retrieved on 2016-02-04.

- ↑ South Carolina State Gemstone - Amethyst. Sciway.net (1969-06-24). Retrieved on 2016-02-04.

- ↑ THE GEMSTONE BOOK Gemstones, Organic Substances & Artificial Products — Terminology & Classification (PDF). The World Jewellery Confideration (CIBJO). 2012.

- ↑ "Amethyst Jewelry and Gemstones Information - International Gem Society IGS". gemsociety.org. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |