Shanghai International Settlement

| Shanghai International Settlement 上海公共租界 | ||||||

| International Settlement | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Motto Omnia Juncta in Uno (Latin) "All Joined into One" | ||||||

| ||||||

| History | ||||||

| • | Established | 1863 | ||||

| • | Disestablished | 1941 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | 1925 | 22.59 km2 (9 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 1910 | 501,561 | ||||

| • | 1925 | 1,137,298 | ||||

| Density | 50,345.2 /km2 (130,393.5 /sq mi) | |||||

| Today part of | Huangpu District, Jing'an District, Hongkou District and Yangpu District, Shanghai Municipality | |||||

The Shanghai International Settlement (Chinese: 上海公共租界; pinyin: Shànghǎi Gōnggòng Zūjiè; Shanghainese: Zånhae Konkun Tsyga) originated from the 1863 merger of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, parts of the Qing Empire held extraterritorially under the terms of a series of Unequal Treaties.

The settlements were established following the defeat of the Qing army by the British in the First Opium War (1839–1842). Under the terms of the Treaty of Nanking, the five treaty ports including Shanghai were opened to foreign merchants, overturning the monopoly then held by the southern port of Canton (Guangzhou) under the Canton System. The British also established a base on Hong Kong under an extensive lease. American and French involvement followed closely on the heels of the British and their enclaves were established north and south, respectively, of the British area.

Unlike the colonies of Hong Kong and Weihaiwei, which were sovereign British territories, the foreign concessions in Shanghai originally remained Chinese sovereign territory. However, during the Small Sword Society uprising of 1853–55, the Qing government gave up sovereignty in the concessions to the foreign powers in exchange of their support to suppress the rebellion.[1] In 1854, the three countries created the Shanghai Municipal Council to serve all their interests, but, in 1862, the French concession dropped out of the arrangement. The following year the British and American settlements formally united to create the Shanghai International Settlement. As more foreign powers entered into treaty relations with China, their nationals also became part of the administration of the settlement, but it always remained a predominantly British affair until the growth of Japan's involvement in the late 1930s.

The international settlement came to an abrupt end in December 1941 when Japanese troops stormed in immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor. In early 1943, new treaties signed by Chiang Kai-shek's Republican government formally ended the extraterritorial privileges of Americans and Britons, although its terms were moot until the recovery of Shanghai following Japan's 1945 surrender. The French later surrendered their privileges in a separate 1946 agreement.

History

Arrival of the Americans, British, and other Europeans

While Europeans had already shown interest in Shanghai's strategic position as a port, the first settlement in Shanghai for foreigners was the British settlement, which was opened in 1843 under the terms of the Treaty of Nanking following the first Anglo-Chinese Opium War. On the orders of Sir Henry Pottinger, first Governor-general of Hong Kong, Captain George Balfour of the East India Company's Madras Artillery arrived as Britain's first consul in Shanghai on 8 November 1843 aboard the steamer Medusa.[2] The next morning Balfour sent word to the circuit intendant of Shanghai, Gong Mujiu (then romanized Kung Moo-yun), requesting a meeting, at which he indicated his desire to find a house to live in. Initially Balfour was told no such properties were available, but on leaving the meeting, he received an offer from a pro-British Cantonese named Yao to rent a large house within the city walls for four hundred dollars per annum. Balfour, his interpreter Walter Henry Medhurst, surgeon Dr. Hale and clerk A. F. Strachan moved into the luxuriously furnished 52-room house immediately.[3]

It served as the consulate during construction of a Western-style building within the official Settlement boundaries just to the south of Suzhou Creek. This was completed within a year. This soon became the epicenter of the British settlement. Afterward both the French and the Americans signed treaties with China that gave their citizens extraterritorial rights similar to those granted to the British, but initially their respective nationals accepted that the foreign settlement came under British consular jurisdiction.

The Sino-American Treaty of Wanghia was signed in July 1844 by Chinese Qing government official Qiying, the Viceroy of Liangguang, who held responsibility for the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi, and Massachusetts politician Caleb Cushing (1800–1879), who was dispatched with orders to "save the Chinese from the condition of being an exclusive monopoly in the hands of England" as a consequence of the 1842 Nanking treaty. Under the Treaty of Wanghia, Americans gained the same rights as those enjoyed by the British in China's treaty ports. It also contained a clause that effectively carved out Shanghai as an extraterritorial zone within Imperial China, though it did not actually give the American government a true legal concession.[4]

It was only in 1845 that Britain followed in America's footsteps and signed a land-deal to allow Britons to rent land in Shanghai in perpetuity. The American consular presence did not create a problem for the British because it was never intended to have a post in person. Since American traders in China were prohibited from engaging in the opium trade (though almost all were active in this trade), their business transactions were conducted under the auspices of British firms. The only serious incident of political complaint against the Americans was in 1845, when the Stars and Stripes was raised by the acting US Consul, Henry G. Wolcott, who had just arrived in the city. Neither the British nor the Chinese governor approved of the display. In 1848, France established its own French concession under French consular jurisdiction, squeezed between the British settlement to the north and the Chinese walled city to the south.

During the Taiping Rebellion, with the Concessions effectively landlocked by both the Manchu government and Small Swords Society rebels, the Western residents of the Shanghai International Settlement, known as "Shanghailanders", refused to pay taxes to the Chinese government except for land and maritime rates (nominally because Shanghai's customs house had been burnt down). They also claimed the right to exclude Chinese troops from the concession areas. While the Settlement had at first disallowed non-foreigners from living inside its boundaries, a large number of Chinese were allowed to move into the International Settlement to escape the Taipings or seek better economic opportunities. Chinese entry was subsequently legalised and continued to grow.

Municipal Council

On 11 July 1854 a committee of Western businessmen met and held the first annual meeting of the Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC, formally the Council for the Foreign Settlement North of the Yang-king-pang), ignoring protests of consular officials, and laid down the Land Regulations which established the principles of self-government. The aims of this first Council were simply to assist in the formation of roads, refuse collection, and taxation across the disparate Concessions.

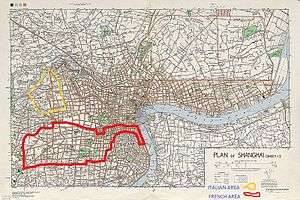

In 1863 the American concession—land fronting the Huangpu River to the north-east of Soochow Creek (Suzhou Creek)—officially joined the British Settlement (stretching from Yang-ching-pang Creek to Suzhou Creek) to become the Shanghai International Settlement. The French concession remained independent and the Chinese retained control over the original walled city and the area surrounding the foreign enclaves. This would later result in sometimes absurd administrative outcomes, such as needing three drivers' licenses to travel through the complete city.

By the late-1860s Shanghai's official governing body had been practically transferred from the individual concessions to the Shanghai Municipal Council (工部局, literally "Works Department", from the standard English local government title of 'Board of works'). The British Consul was the de jure authority in the Settlement, but he had no actual power unless the ratepayers (who voted for the Council) agreed. Instead, he and the other consulates deferred to the Council.

The Council had become a practical monopoly over the city's businesses by the mid-1880s. It bought up all the local gas-suppliers, electricity producers and water-companies, then — during the 20th-century — took control over all non-private rickshaws and the Settlement tramways. It also regulated opium sales and prostitution until their banning in 1918 and 1920 respectively.

Until the late-1920s, therefore, the SMC and its subsidiaries, including the police, power station, and public works, were British dominated (though not controlled, since Britain itself had no authority over the Council). Some of the Settlement's actions during this period, such as the May 30th Movement, in which Chinese demonstrators were shot by members of the Shanghai Municipal Police, did embarrass and threaten the British Empire's position in China even though they were not carried out by "Britain" itself.

No Chinese residing in the International Settlement were permitted to join the council until 1928. Amongst the many members who served on the council, its chairman during the 1920s, Stirling Fessenden, is possibly the most notable. An American, he served as the settlement's main administrator during Shanghai's most turbulent era, and was considered more "British" than the council's British members. He oversaw many of the major incidents of the decade, including the May 30th Movement and the White Terror that came with the Shanghai massacre of 1927.

Through an informal agreement, by the 1930s the British had five seats on the Council, the Japanese two and the Americans and others two.[5] At the 1936 Council election, because of their increasing interests in the Settlement, the Japanese nominated three candidates. Only two were elected, which led to a Japanese protest after 323 uncounted votes were discovered. As a result, the election was declared invalid and a new poll held on April 20-21 1936, at which the Japanese nominated only two candidates, leaving the structure of the Council unchanged.[6]

The International Settlement was wholly foreign-controlled, with staff of all nationalities, including British, Americans, Danes, Italians and Germans. In reality, the British held the largest number of seats on the Council and headed all the Municipal departments (British included Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, Newfoundlanders, and South Africans whose extraterritorial rights were established by the United Kingdom treaty).

The only department not chaired by a Briton was the Municipal Orchestra, which was controlled by an Italian.

The Settlement maintained its own fire-service, police force (the Shanghai Municipal Police), and even possessed its own military reserve in the Shanghai Volunteer Corps (萬國商團). Following some disturbances at the British concession in Hankow in 1927, the defences at Shanghai were augmented by a permanent battalion of the British Army, which was referred to as the Shanghai Defence Force (SDF or SHAF),[7] and a contingent of US Marines. Other armed forces would arrive in Shanghai; the French Concession had a defensive force of Annamite troops, the Italians also introduced their own marines, as did the Japanese (whose troops eventually outnumbered the other countries' many times over).

Overall, the International Settlement was not a British possession in the sense that Hong Kong or Weihaiwei were, and was instead ruled as a self-governing treaty port under the terms of the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, supplemented by those of the Treaty of the Bogue signed a year later. Chinese sovereignty still prevailed on the territory, but individuals who were not Chinese and were members of the Fourteen Favoured Nations (Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States) enjoyed extraterritoriality. The SMC did however exercise a considerable degree of political autonomy over both foreign and Chinese within its borders.

Rise of Imperial Japan (20th century)

In the 19th century, Europeans possessed treaty ports in Japan in the same way they held those in China. However, Japan rapidly developed into a modern nation, and by the turn of the 20th century the Japanese had successfully negotiated with all powers to abrogate all unequal treaties with it. Japan stood alongside the other European powers as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance during the famous fifty five-day siege of the foreign embassy compound in Peking. Japan entered the 20th century as a rising world power, and with its unequal treaties with the European powers now abrogated, it actually joined in, obtaining an unequal treaty with China granting extraterritorial rights under the Treaty of Shimonoseki signed in 1895.

In 1915, during the First World War, Japan overtook Britain as the country with the largest number of foreign residents in Shanghai. In 1914 they sided with Britain and France in the war and conquered all German possessions in China. By the beginning of the 1930s, Japan was swiftly becoming the most powerful national group in Shanghai and accounted for some 80% of all extraterritorial foreigners in China. Much of Hongkew, which had become an unofficial Japanese settlement, was known as Little Tokyo.

In 1931, supposed "protection of Japanese colonists from Chinese aggression" in Hongkew was used as a pretext for the Shanghai Incident, when Japanese troops invaded Shanghai. From then until the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) Hongkew was almost entirely outside of the SMC's hands, with law and protection enforced to varying degrees by the Japanese Consular Police and Japanese members of the Shanghai Municipal Police.

Japanese take over rest of Shanghai (1937)

In 1932 there were 1,040,780 Chinese living within the International Settlement, with another 400,000 fleeing into the area after the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937. For the next five years, the International Settlement and the French Concession were surrounded by Japanese occupiers and Chinese revolutionaries, with conflict often spilling into the Settlement's borders. In 1941, the Japanese launched an abortive political bid to take over the SMC: during a mass meeting of ratepayers at the Settlement Race Grounds, a Japanese official leaped up and shot William Keswick, then Chairman of the Council. While Keswick was only wounded, a near riot broke out.[8]

Evacuation of British garrison

Britain evacuated its garrisons from mainland Chinese cities, particularly Shanghai, in August 1940.[9]:299

Japanese occupy the International Settlement (1941)

Anglo-American influence effectively ended after 8 December 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Army entered and occupied the British and American controlled parts of the city in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. The French and Americans surrendered without a shot, while the only British riverboat in Shanghai, HMS Peterel, refused to surrender and was sunk although nobody was killed.

European Shanghai residents were forced to wear armbands to differentiate them, were evicted from their homes, and — just like Chinese citizens — were liable to maltreatment. All were liable for punitive punishments, torture and even death during the period of Japanese occupation. The Japanese sent European and American citizens to be interned at the Lunghua Civilian Assembly Center, a work camp on what was then the outskirts of Shanghai. Survivors of Lunghua were released in August 1945.[10]

Amongst all this, Shanghai was notable for a long period as the only place in the world that unconditionally offered refuge for Jews escaping from the Nazis.[11] These refugees often lived in squalid conditions in an area known as the Shanghai Ghetto in Hongkew. On 21 August 1941 the Japanese government closed Hongkew to Jewish immigration.

Return to Chinese rule

In February 1943, the International Settlement was de jure returned to the Chinese as part of the British–Chinese Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extra-Territorial Rights in China and American–Chinese Treaty for Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China with the Nationalist Government of the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-shek. However, because Shanghai was under Japanese control, this was unenforceable. In reply, in July 1943, the Japanese retroceded the SMC to the City Government of Shanghai, which was then in the hands of the pro-Japanese Wang Jingwei Government.

Although the original treaty between Britain and China (the Treaty of Nanking) was signed in 1842 on behalf of the entire British Empire, the new treaty of 1943 was only signed on behalf of the United Kingdom, colonies and British India. It was not signed on behalf of the dominions. Canada signed its own treaty with China the following year.

After the war and the liberation of the city from the Japanese, a Liquidation Commission fitfully met to discuss the remaining details of the handover. By the end of 1945, most westerners not actively involved in the Chinese Civil War (such as intelligence agents, soldiers, journalists etc.) or in Shanghai's remaining foreign businesses, had left the city. With the defeat of the Kuomintang in 1949, the city was occupied by Communist troops and came under the control of Mayor of Shanghai.

The foreign architecture of the International Settlement era can still be seen today along the Bund and in many locations around the city.

Legal system

The International Settlement did not have a unified legal system. The Municipal Council issued Land Regulations and regulations under this, that were binding on all people in the settlement. Other than this, citizens and subjects of powers that had treaties with China that provided for extraterritorial rights were subject to the laws of their own countries and civil and criminal complaints against them were required to be brought against them to their consular courts (courts overseen by consular officials) under the laws of their own countries.

The number of treaty powers had climbed to a maximum of 19 by 1918 but was down to 15 by the 1930s: Great Britain, the United States, Japan, France, Italy, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, Peru, Mexico, and Switzerland. Germany and Austria-Hungary lost their treaty rights after WWI, and Russia gave up her rights as a matter of political expediency. Belgium was declared by China to have lost her rights in 1927.[12] Furthermore, the Chinese government adamantly refused to grant treaty power status to any of the new nations born in the wake of WWI, such as Austria and Hungary (formerly Austria-Hungary), Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, the Baltic States and Finland.

Chinese citizens and citizens of non-treaty powers were subject to Chinese law. Inside the Settlement, cases against them would be brought to the Mixed Court, a court established in the Settlement in the 1870s which existed until 1926. In cases involving foreigners, a foreign assessor, usually a consular officer, would sit with the Chinese magistrate and in many cases acted like a judge. In 1927, a Provisional Court was established with a sole Chinese judge presiding. In 1930, Chinese Special Courts were established which had jurisdiction over all non treaty power individuals and companies in the Settlement.

Two countries, Britain and the United States established formal court systems in China to try cases. The British Supreme Court for China and Japan was established in 1865 and located in its own building in the British Consulate compound and the United States Court for China was established in the US Consulate in 1906. Both courts were occupied by the Japanese on 8 December 1941 and effectively ceased to function from that date.

Currency

The currency situation in China generally was very complicated in the 19th century. There was no unified system. Different parts of China operated different systems, and the Spanish pieces of eight that had been coming from Mexico for a few hundred years on Manila Galleons were current along the China coast. Until the 1840s these silver dollar coins were Spanish coins minted mainly in Mexico City, but from the 1840s these gave way to Mexican republican dollars.

In Shanghai, this complexity represented a microcosm of the complicated economy existing elsewhere along the China coast. The Chinese reckoned in weights of silver, which did not necessarily correspond to circulating coins. One important unit was a tael, a measurement of weight with several different definitions. These included: Customs Taels (for foreign trade), Cotton Taels (for cotton trade), etc. Shanghai had its own tael, which was very similar in weight to the Customs Tael and therefore popular for international business. China also had a mixture of coins, including Chinese Copper Cash coins and Mexican dollars. Paper money was first issued by European and North American colonial banks (one British colonial bank known as the Chartered Bank of India, Australia, and China at one time issued banknotes in Shanghai that were denominated in Mexican dollars).

European and North American currencies did not officially circulate in the International Settlement, except Yen in the Japanese district of "Little Tokyo". Until the year 1873, however, US dollar coins would have reasonably corresponded in size, shape and value to Mexican dollars. Between 1873 and 1900, all silver standard dollars had depreciated to about 50% of the value of the gold standard dollars of the United States and Canada leading to a rising economic depression.

The Chinese themselves officially adopted the dollar unit as their national currency in 1889, and the first Chinese dollar coins, known as yuan, contained an inscription which related their value to an already existing Chinese system of accounts. On the earliest Chinese dollar (yuan) coins it states the words 7 mace and 2 candareens. The mace and candareen were sub-divisions of the tael unit of weight.[13] Banknotes tended to be issued in dollars, either worded as such or as yuan.

Despite the complications arising from a mixture of Chinese and Spanish coinages, there was one overwhelming unifying factor binding all the systems in use: silver. The Chinese reckoned purely in terms of silver, and value was always compared against a weight of silver (hence, the reason large prices were given in tael). It was the strict adherence of the Chinese to silver that caused China and even the British colonies of Hong Kong and Weihaiwei to remain on the silver standard after the rest of the world had changed over to the gold standard. When China began producing official Republican yuan coins in 1934, they were minted in Shanghai and shipped to Nanking for distribution.

Postal services

Shanghai had developed a postal service as early as the Ming Dynasty, but during the treaty port era foreign postal services were organised through their respective consulates. For example, the United States Post Office Department maintained a United States Postal Agency at the Shanghai consulate through which Americans could use the US Post Office to send mail to and from the US mainland and US territories. Starting in 1919 the 16 current regular US stamps were overprinted for use in Shanghai with the city's name, "China", and amounts double their printed face values.[14] In 1922 texts for two of the overprints were changed, thereby completing the Scott catalogue set of K1-18, "Offices in China".

The British originally used British postage stamps overprinted with the local currency amount, but from 1868, the British changed to Hong Kong postage stamps already denominated in dollars. However, in the special case of Shanghai, in the year 1865 the International settlement began to issue its own postage stamps, denominated in the local Shanghai tael unit.

The Shanghai Post Office controlled all post within the Settlement, but post coming in or going out of the treaty port was required to go through the Chinese Imperial Post Office. In 1922 the various foreign postal services, the Shanghai Post Office and the Chinese Post Office were all brought together into a single Chinese Post Office, thus extending the 1914 membership of the Chinese Post Office to the Universal Postal Union to Shanghai Post Office. Some other foreign countries refused to fall under this new postal service's remit, however: for many years, Japan was notable as sending almost all its mail to Shanghai in diplomatic bags, which could not be opened by postal staff.

The General Shanghai Post Office was first located on Beijing Road and moved to the location on Sichuan North Road of the General Post Office Building, Shanghai that is today the Shanghai Post Museum.

Music

International merchants brought with them amateur musical talent that manifested in the creation of the Shanghai Philharmonic Society in 1868 under the baton of French conductor Remusat. In order to remain under the instruction of Remusat, the society offered him the profits of two concerts a year, which was a reasonable deal considering the popularity of their concerts throughout the year.[15] From here, the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra was officially formed in 1879, also under Remusat.[16]

In 1919, the orchestra came under Italian pianist Marco Paci, and it flourished as a main cultural attraction for the public. In an interview regarding the orchestra in 1933, Paci noted that the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra was "now one of the finest symphonic orchestras in the world, comparable, if not superior to any in Europe or America."[17] He also discussed the wide audience to which the symphony performed, including the fact that the Shanghai concert audience included people of various nationalities who had a wide spectrum of pieces and composers that they enjoyed. As a result, the orchestra performed a great selection of pieces, from Beethoven to lesser-known composers such as Bargiel.[18] Internationally noted musicians such as Polish pianist Ignez Friedman visited Shanghai to give guest performances.[19]

In 1938, the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra faced disbandment as the ratepayers in the annual Municipal Council meeting considered reallocating budgets away from the orchestra, since it was "western and unnecessary." However, after much discussion, they decided to keep the orchestra, acknowledging that its educational value was much greater than the cost of keeping it up.[20] The Shanghai Municipal Orchestra had the financial and verbal backing of many other larger countries, including Italy, who donated 50,000 lire to the orchestra,[21] the France Council, who acted as a defending argument for the maintenance of the orchestra,[20] and Japan, whose viscount, Konoye, encouraged the Japanese people to support the orchestra and the culture that it brought to the East.[22]

After 1938, there were several other times during which the Municipal wanted to kill off the orchestra; however, every time, the orchestra had "pheonix-like risen from the ashes."[23] Further on in the article, the editor notes the great educational values of music in bring culture to the East, which was a characteristic of music unique to Shanghai. Additionally, unlike other places in the world, Shanghailanders had a consistently great genuine appreciation for music, which was a common language that brought people of all nations together in celebration. [23]

The people in the International Settlement prided themselves in the high culture that they had even while separated ten thousand miles from home, physically manifested in the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra. After every performance, an article was released in the "Amusements" section of the newspaper, outlining the concert program, praising the success of each concert, and critiquing the musicians and the orchestra as a whole.[24]

In addition to the string orchestra, opera and choral music were favored forms of entertainment. Often, the orchestra would accompany singers as a part of orchestra concerts, in addition to the symphonies and other pieces that they played, or just in choral or opera concerts.[25]

List of Chairmen of the Shanghai Municipal Council

-

Edward Cunningham (25.5.1852 - 21.7.1853)[lower-alpha 1]

Edward Cunningham (25.5.1852 - 21.7.1853)[lower-alpha 1] -

William Shepard Wetmore (21.7.1853 - 11.7.1854)[lower-alpha 1]

William Shepard Wetmore (21.7.1853 - 11.7.1854)[lower-alpha 1] -

James Lawrence Man (11.7.1854 - 1855)

James Lawrence Man (11.7.1854 - 1855) -

Christopher Augustus Fearon (1855)

Christopher Augustus Fearon (1855) -

William Shepard Wetmore (3.1855 - 1855)

William Shepard Wetmore (3.1855 - 1855) -

William Thorbun (1855 - 1856)

William Thorbun (1855 - 1856) -

James Lawrence Man (1.1856 - 31.1.1857)

James Lawrence Man (1.1856 - 31.1.1857) -

George Watson Coutts (31.1.1857 - 1.1858)

George Watson Coutts (31.1.1857 - 1.1858) -

John Thorne (1.1858 - 1.1859)

John Thorne (1.1858 - 1.1859) -

Robert Reid (31.1.1859 - 15.2.1860)

Robert Reid (31.1.1859 - 15.2.1860) -

Rowland Hamilton (15.2.1860 - 2.2.1861)

Rowland Hamilton (15.2.1860 - 2.2.1861) -

William Howard (2.2.1861 - 31.3.1862)

William Howard (2.2.1861 - 31.3.1862) -

Henry Turner (31.3.1862 - 4.4.1863)

Henry Turner (31.3.1862 - 4.4.1863) -

Henry William Dent (4.4.1863 - 25.4.1865)

Henry William Dent (4.4.1863 - 25.4.1865) -

William Keswick (25.4.1865 - 18.4.1866)

William Keswick (25.4.1865 - 18.4.1866) -

F.B. Johnson (18.4.1866 - 3.1868)

F.B. Johnson (18.4.1866 - 3.1868) -

Edward Cunningham (3.1868 - 2.4.1870)

Edward Cunningham (3.1868 - 2.4.1870) -

George Basil Dixwell (2.4.1870 - 4.4.1871)

George Basil Dixwell (2.4.1870 - 4.4.1871) -

John Dent (4.4.1871 - 1.1873)

John Dent (4.4.1871 - 1.1873) -

Robert Inglis Fearon (1.1873 - 16.4.1874)

Robert Inglis Fearon (1.1873 - 16.4.1874) -

John Graeme Purdon (16.4.1874 - 1876)

John Graeme Purdon (16.4.1874 - 1876) -

Alfred Adolphus Krauss (1876 - 1.1877)

Alfred Adolphus Krauss (1876 - 1.1877) -

J. Hart (1.1877 - 16.1.1879)

J. Hart (1.1877 - 16.1.1879) -

Robert "Bob" W. Little (16.1.1879 - 30.1.1882)

Robert "Bob" W. Little (16.1.1879 - 30.1.1882) -

H.R. Hearn (30.1.1882 - 1882)

H.R. Hearn (30.1.1882 - 1882) -

Walter Cyril Ward (1882 - 1883)

Walter Cyril Ward (1882 - 1883) -

Alexander Myburgh (1883 - 22.1.1884)

Alexander Myburgh (1883 - 22.1.1884) -

James Johnstone Keswick (22.1.1884 - 22.1.1886)

James Johnstone Keswick (22.1.1884 - 22.1.1886) -

A.G. Wood (22.1.1886 - 1889)

A.G. Wood (22.1.1886 - 1889) -

John Macgregor (1889 - 5.1891)

John Macgregor (1889 - 5.1891) -

John Graeme Purdon (5.1891 - 1.1893)

John Graeme Purdon (5.1891 - 1.1893) -

John Macgregor (1.1893 - 7.11.1893)

John Macgregor (1.1893 - 7.11.1893) -

James Lidderdale Scott (11.1893 - 26.1.1897)

James Lidderdale Scott (11.1893 - 26.1.1897) -

Edward Albert Probst (26.1.1897 - 21.4.1897)

Edward Albert Probst (26.1.1897 - 21.4.1897) -

Albert Robson Burkill (12.5.1897 - 1.1898)

Albert Robson Burkill (12.5.1897 - 1.1898) -

James S. Fearon (1.1898 - 8.1899)

James S. Fearon (1.1898 - 8.1899)

-

Frederick Anderson (8.1899 – 1.1900)

Frederick Anderson (8.1899 – 1.1900) -

Edbert Ansgar Hewett (8.1900 - 25.1.1901)

Edbert Ansgar Hewett (8.1900 - 25.1.1901) -

John Prentice (26.1.1901 - 25.1.1902)

John Prentice (26.1.1901 - 25.1.1902) -

William George Bayne (25.1.1902 - 1904)

William George Bayne (25.1.1902 - 1904) -

Frederick Anderson (1904 - 25.1.1906)

Frederick Anderson (1904 - 25.1.1906) -

Cecil Holliday (25.1.1906 - 24.8.1906)

Cecil Holliday (25.1.1906 - 24.8.1906) -

Henry Keswick (24.8.1906 - 5.1907)

Henry Keswick (24.8.1906 - 5.1907) -

David Landale (5.1907 – 17.1.1911)

David Landale (5.1907 – 17.1.1911) -

Harry De Gray (17.1.1911 - 24.1.1913)

Harry De Gray (17.1.1911 - 24.1.1913) -

Edward Charles Pearce (24.1.1913 - 17.2.1920)

Edward Charles Pearce (24.1.1913 - 17.2.1920) -

Alfred Brooke-Smith (17.2.1920 - 17.3.1922)

Alfred Brooke-Smith (17.2.1920 - 17.3.1922) -

H.G. Simms (17.3.1922 - 12.10.1923)

H.G. Simms (17.3.1922 - 12.10.1923) -

Stirling Fessenden (12.10.1923 - 5.3.1929)

Stirling Fessenden (12.10.1923 - 5.3.1929) -

Harry Edward Arnhold (5.3.1929 - 1930)

Harry Edward Arnhold (5.3.1929 - 1930) -

Ernest Brander Macnaghten (1930 - 22.3.1932)

Ernest Brander Macnaghten (1930 - 22.3.1932) -

A.D. Bell (22.3.1932 - 27.3.1934)

A.D. Bell (22.3.1932 - 27.3.1934) -

Harry Edward Arnhold (27.3.1934 - 4.1937)

Harry Edward Arnhold (27.3.1934 - 4.1937) -

Cornell Franklin (4.1937 - 4.1940)

Cornell Franklin (4.1937 - 4.1940) -

William Johnstone "Tony" Keswick (4.1940 - 1.5.1941)

William Johnstone "Tony" Keswick (4.1940 - 1.5.1941) -

John Hellyer Liddell (1.5.1941 - 5.1.1942)

John Hellyer Liddell (1.5.1941 - 5.1.1942) -

Katsuo Okazaki (5.1.1942 - 1.8.1943)

Katsuo Okazaki (5.1.1942 - 1.8.1943)

Notable people born in the International Settlement

- J. G. Ballard, writer. His acclaimed novel Empire of the Sun is set in the International Settlement and other parts of Shanghai.

- Mary Hayley Bell, actress

- Eileen Chang, Chinese writer

- Edmond H. Fischer, Nobel Prize winner

- Thierry Jordan, Archbishop of Reims

- Jane Scott, Duchess of Buccleuch

- China Machado model, Harpers Bazaar Editor, TV Producer, Designer

Relation with the French Concession

The French Concession was governed by a separate municipal council, under the direction of the Consul General. The French Concession was not part of the International Settlement.

Notes

References

Citations

- ↑ Li, Xiaobing (2012). China at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 415. ISBN 9781598844153.

- ↑ Hawkes, Francis Lister (4 March 2007), A Short History of Shanghai, Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, retrieved 10 March 2014

- ↑ Hauser 1940, p. 10.

- ↑ Sergeant, H. Shanghai (1998) at pp 16–17.

- ↑ "Shanghai International Settlement Elections: Japan Demand New Ballot". Dundee Evening Telegraph. 26 March 1936. Retrieved 18 November 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Johnstone, William Crane (1937). The Shanghai Problem. Stanford University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-8047-1066-4.

- ↑ The Queen's join the China Station 1927

- ↑ The Lewiston Daily, Sunday 12 April 1940

- ↑ Lorraine Glennon. Our Times: An Illustrated History of the 20th Century. October 1995. ISBN 9781878685582

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/lunghua-civilian-assembly-centre-teacher-to-reveal-grim-history-of-site-of-j-g-ballards-internment-camp-9180216.html

- ↑ Wasserstein, B. Secret War in Shanghai (1999) at pp 140–150.

- ↑ William C. Johnstone, "International Relations: The Status of Foreign Concessions and Settlements in the Treaty Ports of China", The American Political Science Review, no 5, Oct. 1937, p. 942.

- ↑ Standard Catalogue of World Coins. Bruce&Michael

- ↑ The Shanghai Overprints of 1919

- ↑ "Shanghai". The North-China Herald and Market Report. 6 February 1968. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "The Philharmonic Concert at Masonic Hall". The North - China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette. 24 December 1879. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "Musical Quiz Elicits Some Unusual Comments From Paci About Municipal Orchestra". The China Press. 20 June 1933. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "Amusements: Mr. Iburg's Final Concert". The North - China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette. 29 June 1880. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "To Appear With Orchestra: Ignaz Friedman Booked To Play With Orchestra Noted Polish Pianist To Be Featured On Next Symphony Program". The China Press. 1 November 1933. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- 1 2 "S.M.C. Ratepayers' Meeting". The North - China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette. 14 April 1938. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "Italy's Gift to Shanghai: Italian Government's Donation of 50,000 Lire to Shanghai Municipal Orchestra". The North - China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette. 5 October 1938. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "Viscount Konoye Urges That Japanese Support Orchestra". The China Press. 20 February 1936. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- 1 2 "THE NEW ORCHESTRA". The China Press. 18 April 1936. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "Shanghai Philharmonic Society's Concert". The North - China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette. 9 January 1891. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "Professor Sternberg's Symphony Concert". The North - China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette. 23 May 1900. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

Sources

- Bergere, Marie-Claire: Shanghai: China's Gateway to Modernity. Transl. from French by Janet Lloyd. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8047-4905-3.

- Bickers, Robert, "Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai", Allen Lane History.

- Hauser, Ernest O. (1940). Shanghai: City for Sale. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co.

- Earnshaw, Graham (2012). Tales of Old Shanghai. Earnshaw Books. ISBN 9789881762115.

- Haan, J.H. "Origin and Development of the Political System in the Shanghai International Settlement", Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 22 (1982):31–64.

- Haan, J.H. "The Shanghai Municipal Council, 1850–1865: Some Biographical Notes", Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 24 (1984):207–229.

See also

- Astor House Hotel (Shanghai)

- British Supreme Court for China and Japan

- The Bund

- China Marines

- Former Consulate-General of the United Kingdom, Shanghai

- Klaus Mehnert

- List of historic buildings in Shanghai

- Richard Sorge

- Shanghai Club

- Shanghai French Concession

- Shanghai Municipal Police

- Tilanqiao Prison (formerly Ward Road Gaol)

- United States Court for China

- When We Were Orphans

- The Blue Lotus

- Empire of the Sun

External links

Media related to Shanghai International Settlement at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shanghai International Settlement at Wikimedia Commons