Amboyna massacre

The Amboyna massacre[1] was the 1623 torture and execution on Ambon Island (present-day Maluku, Indonesia) of twenty men, including ten of whom were in the service of the English East India Company, and Japanese and Portuguese traders, by agents of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), on accusations of treason.[2] It was the result of the intense rivalry between the East India companies of England and the United Provinces in the spice trade and remained a source of tension between the two nations until late in the 17th century.

Background

From its inception, the Dutch Republic was at war with the Spanish crown (who was in a dynastic union with the Portuguese crown from 1580 to 1640). In 1598 the king of Spain embargoed Dutch trade with Portugal, and so the Dutch went looking for spices themselves in the areas that had been apportioned to Portugal under the Treaty of Tordesillas. In February, 1605 Steven van der Hagen, admiral of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), conquered the Portuguese fortress of Victoria at Amboyna,[3] thereby taking over the Portuguese trading interests at Victoria. Like other European traders[4] they tried to obtain a local monopsony in the spice trade by keeping out the factors of other European countries by force of arms. This especially caused strife with the English East India Company[5] while the actions of the interloper Sir Edward Michelborne incensed the Dutch.[6] Unavoidably, the national governments got involved, and this threatened the congenial relations between James I of England and the Dutch States General.

King James I and the Netherlands States General caused the two warring companies to conclude a Treaty of Defence in London in 1619 creating cooperation in the East Indies. The market in spices was divided between them in a fixed proportion of two to one (both companies having legal monopolies in their home markets); a Council of Defense was instituted in Batavia that was to govern the merchants of both companies; most important, those merchants were now to share trading posts peacefully, though each company was to retain and police the posts it had occupied. The Dutch interpreted this latter provision to mean that each company had legal jurisdiction over the employees of both companies in the places it administered. Contrarily, the English maintained, on the basis of the arbitration-article 30 of the treaty, that only the Council of Defence would have jurisdiction over employees of the "other" company. This proved to be an important difference of opinion in the ensuing events.

The incident

Despite the treaty, relations between the two companies remained tense. Both parties developed numerous grievances against each other including bad faith, non-performance of treaty-obligations, and "underhand" attempts to undercut each other in the relations with the indigenous rulers with whom they dealt. In the Amboyna region, local VOC-governor Herman van Speult had trouble, in late 1622, with the Sultan of Ternate, who showed signs of intending to switch allegiance to the Spanish. Van Speult suspected the English of secretly stirring up these troubles.[7]

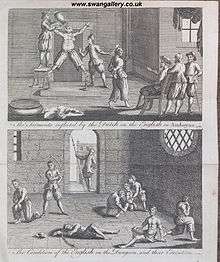

As a result, the Dutch at Amboyna became suspicious of the English traders that shared the trading post with them. These vague suspicions became concrete when in February 1623 one of the Japanese mercenary soldiers (ronin, or masterless samurai in the employ of the VOC[8]) was caught in the act of spying on the defenses of the fortress Victoria. When questioned under torture the soldier confessed to a conspiracy with other Japanese mercenaries to seize the fortress and assassinate the governor. He also implicated the head of the English factors, Gabriel Towerson, as a member of the conspiracy. Subsequently, Towerson and the other English personnel in Amboina and adjacent islands were arrested and questioned.[9] In most, but not all,[10] cases torture was used during the questioning.[11] Torture consisted of having water poured over the head, around which a cloth was draped, bringing the interrogated repeatedly close to suffocation (this is today called waterboarding). This was the usual investigative torture in the Dutch East Indies at the time.[12] According to Dutch trial records, most suspects confirmed that they were guilty as charged, with or without being tortured. Since the accusation was treason, those that had confessed (confession being necessary for conviction under Roman Dutch law) were sentenced to death by a court consisting of the Governor and Council of the VOC at Amboina. However, four of the English and two of the Japanese condemned were subsequently pardoned.[13] Consequently, ten Englishmen,[14] nine Japanese[15][16][17][18][19] and one Portuguese[20] (the latter being employees of the VOC), were executed. On 9 March 1623 they were beheaded, and the head of the English captain, Gabriel Towerson, was impaled on a pole for all to see.

Aftermath

In the summer of 1623, the Englishmen who had been pardoned and acquitted sailed to Batavia and complained to the Dutch governor-general Pieter de Carpentier and the Council of Defence about the Amboyna affair, which they said was a false accusation based upon a fantasy and that the confessions had been obtained only by severe torture. When the English could not get redress in Batavia, they traveled to England, accompanied by the English factor at Batavia. Their story caused an uproar in England. The directors of the EIC asked that the English government demand reparations from the VOC and exemplary punishment of the Amboina judges from the Dutch government.

According to the English ambassador Sir Dudley Carleton, the version of events as he presented it also caused much anger at the VOC in Dutch government circles. However, the VOC soon presented its version of events which contradicted the English version in essential respects. The Dutch States General proposed a joint Anglo-Dutch commission of inquiry to establish the facts, but the suggestion was rejected by the English as too time-consuming. The Dutch did not want to execute the culprits summarily as the English wished, so the States General commissioned an inquiry by delegated judges from the highest courts in the Dutch republic to investigate the matter. The Amboyna judges were recalled from the East-Indies and put under house arrest.[21]

The trial progressed slowly because the court of inquiry wished to cross-examine the English witnesses. The English government balked at this demand because it felt it could not compel the witnesses to travel to the Republic. Besides, as the English based their case on the incompetence of the court to try employees of the EIC (according to the English interpretation of the Treaty of Defence), the executions were ipso facto illegal in the English view and, therefore, constituted a judicial murder. This contention could be decided without an examination of the witnesses. The Dutch, however, maintained that the court at Amboyna had been competent and therefore concentrated their inquiry on possible misconduct of the judges.[22]

The English witnesses traveled to the Dutch republic in 1630 with Sir Henry Vane the Elder. They were made available to the court under restrictive conditions.[23] The draft-verdict of the court (an acquittal of the accused) was presented to the new English king Charles I in 1632 for approval (as agreed beforehand by the two governments). It was rejected, but the accused judges were released.[24]

In 1654, Towerson's heirs and others received £3,615 and the EIC £85,000 from the VOC in compensation for the events at Amboyna.[25]

War of pamphlets

The East India Company was unhappy with the outcome, and in 1632 its directors published an exhaustive brochure, comprising all the relevant papers, with extensive comments and rebuttals of the Dutch position.[26] The Dutch had already sought to influence public opinion with an anonymous pamphlet, probably authored by its Secretary, Willem Boreel in 1624. At the time, ambassador Carleton had procured its suppression as a "libel" by the States General. However, an English minister in Flushing, John Winge, inadvertently translated it and sent it to England, where it displeased the East India Company.[27]

The East India Company brochure contained the gruesome details of the tortures, as related in its original "Relation".[9] These details may not all have been true, but they were calculated to excite much anger at the Dutch. For this reason they were useful for propaganda purposes whenever the exigencies of the diplomatic situation demanded a rekindling of resentment of English public opinion against the Dutch.

So when Oliver Cromwell needed a pretext for the First Anglo-Dutch war, the brochure was reprinted as "A Memento for Holland." (1652).[28] The Dutch lost the war and were forced to accept a condition in the 1654 Treaty of Westminster, calling for the exemplary punishment of the culprits "then still alive."[29] However, no culprits appear to have been still alive at the time. Moreover, after arbitration on the basis of the treaty, the heirs of the English victims were awarded a total of £3615 in compensation.[30]

The brochure and its allegations also played a role at the start of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The annexation of the Dutch colony New Netherland was justified with a rather farfetched reference to the Amboyna Massacre.[31] The Treaty of Breda (1667) ending this war appeared to have finally settled the matter.

However, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the matter was again raised in a propagandistic context. John Dryden wrote a play, entitled "Amboyna or the Cruelties of the Dutch to the English Merchants," apparently at the behest of his patron who had been one of the chief negotiators of the Secret treaty of Dover that caused England's entry into that war. The play embellishes the affair by attributing the animus of Governor Van Speult against Gabriel Towerson to an amorous rivalry between the (fictitious) son of the governor and Towerson over an indigenous princess. After the son rapes the beauty, Towerson kills the son in a duel. The governor then takes his revenge in the form of the "massacre."[32]

Jonathan Swift refers to the massacre in Book 3, Chapter 11 of Gulliver's Travels (1726). Gulliver pretends to be a "Hollander" and boards a Dutch ship named the Amboyna when he leaves Japan. He conceals from the crew the fact that he has not performed the ceremony demanded by the Japanese of "trampling upon the Crucifix" because, "if the secret should be discovered by my countrymen, the Dutch, they would cut my throat in the voyage."

See also

References

- ↑ The old spelling for the name Amboina/Ambon is used, because "Amboyna massacre" is a common expression in the English language. For that reason the word "massacre" is retained, though the incident was not a massacre in the usual sense of the word.

- ↑ Shorto, p. 72.; State Papers, No. 499I

- ↑ Old spelling of the English name for Ambon Island

- ↑ The English, for instance, tried to do the same at Run.

- ↑ Best known is the expedition of Sir Thomas Dale in 1619, which resulted in a naval engagement between the English and the Dutch, and caused the Dutch to temporarily evacuate Java;Jourdain, pp. lxix–lxxi

- ↑ "The “Separate Voyages” of the Company". Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ State Papers, No. 537I

- ↑ Japanese mercenaries were also in the service of the Portuguese and the Siamese kings; see Yamada Nagamasa

- 1 2 State Papers, No. 499I

- ↑ A number of the factors from the adjacent islands(Powle, Ladbrooke, Ramsey, and Sadler) had unshakeable "alibis" and were therefore left in peace; State Papers, No. 499I

- ↑ Under Roman Dutch Law, as under other continental European systems of law, based on the ius civile, torture was allowed in specific circumstances; Evans pp. 4–6. Though the English common law did not need torture for investigative purposes (as a confession was not required for conviction), the English did torture in cases of treason. For this purpose, a royal or Privy Council warrant was required, based on the Royal Prerogative.For a contemporary instance see the entry about the torture in February 1620/21 of one "Peacock of Cambridge" in the diary of William Camden in connection with the trial of Thomas Lake. A warrant for the torture of John Felton was quashed in 1628.

- ↑ According to governor Frederick de Houtman, a predecessor of Van Speult at Amboina; State Papers, Nos. 661II, 684. According to the English version of events, even more sadistic forms of torture were used. This was later disputed by the Dutch; State Papers, No. 499I

- ↑ Collins, Beaumont, Webber and Sherrocke; Soysimo en Sacoute; State Papers, No. 499I

- ↑ Gabriel Towerson, agent of the EIC at Amboina; Samuel Colson, factor at Hitto; Emanuel Thompson, assistant at Amboina; Tymothy Johnson, assistant at Amboina; John Wetherall, factor at Cambello; John Clarke, assistant at Hitto; William Griggs, factor at Larica; John Fardo, steward of the English house at Amboina; Abel Price, surgeon; and Robert Browne, tailor; State Papers, No. 499I

- ↑ Hiheso, Tsiosa, Suisa, all from Firando; Stanley Migiel, Pedro Congie, Thome Corea, all from Nangasacque; Quiondayo of Coraets; Isabinda of Tsoucketgo; Zanchoe of Fisien; all spellings as rendered in State Papers, No. 499I

- ↑ http://www.eablanchette.com/_supportdocs/session2.html

- ↑ Great Britain. Public Record Office (1878). Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series ...: Preserved in the Public Record Office ... pp. xxv–.

- ↑ Great Britain. Public Record Office (1878). Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series ...: East Indies, China and Japan, 1513. Longman. pp. 25–.

- ↑ https://muse.jhu.edu/article/426730

- ↑ Augustine Perez; State Papers, No. 499I

- ↑ State Papers, Nos. 535, 567II, 661I, 695

- ↑ State Papers, Nos. 537I, 567II, 591, 661I

- ↑ Resolutiën, 30 April 1630, 19

- ↑ After the Amboyna Massacre, the English reduced their interest in the East Indies and focused their attention on the Indian Subcontinent. The Amboyna Massacre was cited as one of the causes for the move, but, in fact, the decision was made before the massacre occurred.

- ↑ Bruce, John (1810). Annals of the Honorable East-India Company. Black, Parry, and Kingsbury. p. 72.

- ↑ Reply

- ↑ State Papers, Nos. 537I, 548, 551, 555

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 297

- ↑ Art. 27 of the Treaty.

- ↑ Hunter and Roberts, p. 427

- ↑ Second Part of the Tragedy of Amboyna; Schmidt, p.297

- ↑ Zwicker, p. 141; Schmidt, p. 296

Further reading

- Coolhaas, W. Ph., "Aanteekeningen en opmerkingen over den zoogenaamden Ambonschen moord", in: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, Vol. 101 (1942), p. 49–93

- Evans, M.D. (1998): Preventing Torture: A Study of the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Oxford U.P.; 512 pages, ISBN 0-19-826257-4

- Hunter, W.W., Roberts, P.E. (1899): A History of British India, Longman, Green & Co.

- Jourdain, J. e.a. (1905): The Journal of John Jourdain, 1608–1617, Describing His Experiences in Arabia, India, and the Malay Archipelago, Hakluyt Society

- Markley, R. (2006): The Far East and the English Imagination, 1600–1730, Cambridge U.P.; 324 pages ISBN 0-521-81944-X

- Milton, G., Nathaniel’s Nutmeg: How one man's courage changed the course of history, 2000 Sceptre; 400 pages, ISBN 0-340-69676-1

- Records of the special committee of judges on the Amboyna Massacre (Ambonse moorden), at the Nationaal Archief of the Netherlands in The Hague (part of the records of the Staten Generaal, records number 1.01.07, inventory number 12551.62)

- A Reply to the Remonstrance of the Bewinthebbers or Directors of the Dutch East-India Company, East-India Company (1632)

- Shorto, R., The Island at the Center of the World. Doubleday 2004

- Schmidt, B. (2001): Innocence abroad: The Dutch imagination and the New World, 1570–1670, Cambridge University Press; 480 pages, ISBN 0-521-80408-6

- Zwicker, S.N. (2004): The Cambridge Companion to John Dryden, Cambridge U.P., 318 pages ISBN 0-521-53144-6

External links

- Sainsbury, W. Noel (ed.), Calendar of State Papers Colonial, East Indies, China and Japan – 1622–1624, Volume 4 (1878)

- (in Dutch) Resolutiën Staten-Generaal 1626–1630, Bewerkt door I.J.A. Nijenhuis, P.L.R. De Cauwer, W.M. Gijsbers, M. Hell, C.O. van der Meij en J.E. Schooneveld-Oosterling