Alice de Janzé

| Alice de Janzé | |

|---|---|

|

Alice in Chicago, 1919 | |

| Born |

28 September 1899 Buffalo, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

30 September 1941 (aged 42) Gilgil, Kenya |

| Occupation | Heiress |

| Spouse(s) |

Frédéric de Janzé (m. 1921–27) Raymond de Trafford (m. 1932–37) |

| Children |

Nolwén Louise Alice de Janzé Paola Marie Jeanne de Janzé |

| Parent(s) |

William Edward Silverthorne Julia Belle Chapin |

Alice de Janzé, née Silverthorne (28 September 1899 – 30 September 1941),[1] also known as Alice de Trafford and holder of the noble title Comtesse (Countess) de Janzé for a few years, was an American heiress who spent years in Kenya as a member of the Happy Valley set of colonials. She was connected with numerous scandals, including the attempted murder of her lover in 1927, and the 1941 murder of The 22nd Earl of Erroll in Kenya. Her tempestuous life was marked by promiscuity, drug abuse and several suicide attempts.

Growing up in Chicago and New York, Silverthorne was one of the most prominent American socialites of her time; a relative of the powerful Armour family, she was a multi-millionaire heiress. She entered French aristocracy in the early 1920s, when she married Count de Janzé. In the mid-1920s, she was introduced to the infamous Happy Valley set, a community of white expatriates in East Africa, notorious for their hedonistic lifestyle. In 1927, she made international news when she shot her lover in a Paris railway station and then turned the gun on herself; they both survived. De Janze stood trial but was only fined a small amount, and was later pardoned by the French state. She further scandalized the public by marrying, and then later divorcing, the man she shot.

In 1941, she was one of several major suspects in the well-publicized murder of her former lover and friend, Lord Erroll, in Kenya. After a long history of numerous failed suicide attempts, she died of a self-inflicted gunshot in September 1941. Her personality has been referenced both in fiction and non-fiction, most notably in the book White Mischief and its film adaptation, where she was portrayed by Sarah Miles.

Early life

Alice was born in Buffalo, Erie County, New York,[1] the only child of textile industrialist William Edward Silverthorne and wife, Julia Belle Chapin (14 August 1871[2] – 2 June 1907)[3] a relative to the Armour family, of meatpacking success through the Armour & Company brand, at the time the largest food products company in the world.[4] Silverthorne was a first cousin, once removed, to J. Ogden Armour and great-niece to Philip Danforth Armour and Herman Ossian Armour, the granddaughter of their sister Marietta, who left much of her estate to her mother, Julia, in 1897.[5] William and Julia were married in Chicago on 8 June 1892,[6][7] the city where Alice spent most of her childhood and adolescence, living with her parents in the affluent Gold Coast district.[8] Alice herself became a favorite of her cousin, J. Ogden Armour. Her family's great wealth prompted her childhood friends to take a cue from her surname and give her the nickname "Silver Spoon".[9]

Julia Silverthorne died of complications from tuberculosis when Alice was only eight,[4] although biographer Paul Spicer argues that her death was a result from being locked out of the house by her husband during a freezing night six months earlier.[10] Alice, who inherited a large estate from her mother, was herself an asymptomatic consumptive from birth.[4] Following her mother's death, Alice was raised by a German governess in large houses in New York; her alcoholic father[11] was frequently absent due to his professional obligations. Contrary to her wishes, William Silverthorne quickly remarried in 1908,[9] and had five children with his second wife, Louise Mattocks. Many of them did not survive; Alice's half-siblings included William Jr. (1912–1976), Victoria Louise (died in infant|infancy in 1914), Patricia (1915–?), Lawrence (1918–1923) and an unnamed girl who died in infancy in 1910.[12] William later divorced Mattocks and married twice more.[3]

With her father's encouragement, the precocious Alice was introduced to wild social life in her early adolescence. She was one of the more prominent socialites of Chicago, frequenting the fashionable nightclubs of the time. Her father also took her on several European tours and encouraged her image as a prominent debutante. These years of wild youth left Alice with a chronic melancholia;[4] it is possible that she suffered from cyclothymia, a strain of bipolar disorder.[13]

Her father soon lost custody of her; an uncle from her mother's side assumed the role of her legal guardian and then proceeded to place her at a boarding school in Washington D.C.[9][11] Journalist Michael Kilian believes this was because William Silverthorne had an incestuous relationship with his adolescent daughter, in which she lost her virginity to her father,[14][15] until one of her uncles intervened and took the case to the court.[8][16] Spicer disagrees that her relationship with her father was improper.[10] Regardless of the court decision, after fourteen-year-old Alice came to live with the Armours in New York she then openly travelled with her father to the French Riviera, where Kilian claims Silverthorne openly sported her as his mistress and allowed her to keep a black panther as a pet.[8] In later years, she was famous for parading the animal up and down the Promenade des Anglais in Nice.[11]

1919–1927: Marriage and the Happy Valley set

In 1919, Alice moved back to Chicago to live with her aunts, Mrs. Francis E. May (née Alice Chapin) and Mrs. Josephine Chapin.[17] Two years later, Alice moved to Paris,where she briefly worked as director of the model department in Jean Patou's atelier,[18] until she met Frédéric Jacques, Comte de Janzé (ca 1896 – 24 December 1933), a well-known French racing driver and heir to an old aristocratic family in Brittany. A participant in the 24 Hours of Le Mans and other races, Frédéric also frequented literary circles and was close friends with Marcel Proust, Maurice Barrès and Anna de Noailles.[19]

Unlike many other American heiresses of the period, Alice had not allowed her family to arrange an advantageous match for her, choosing to take the initiative and pursue a romance with Comte de Janzé on her own.[9] After a romance of only three weeks,[20] the couple married on 21 September 1921 in Chicago,[21] with her new husband reportedly finding her "Silverthorne" surname so charming that he regretted their marriage would take it away from her.[22] Following the ceremony, Alice's aunt, Mrs. J. Ogden Armour, turned over the Armour estate on Long Island to the couple, where they spent two weeks before deciding to permanently settle in Paris, in the Champs-Élysées quarter.[20][23] Their marriage produced two daughters, Nolwén Louise Alice de Janzé (20 June 1922 – 7 March 1989) and Paola Marie Jeanne de Janzé (1 June 1924 – 24 December 2006). Alice was a neglectful mother as Frederic was a neglectful father; the children were primarily brought up in their family chateau in Normandy[11] by governesses and Frédéric's sister.

In 1925, de Janzé and Alice first met and became good friends with Josslyn, 22nd Earl of Erroll, and his wife, Idina, Countess of Erroll, in Montparnasse.[24] Some time later, the young Lord and Lady Erroll decided to invite the de Janzés to spend some time in their home in the so-called 'Happy Valley' in the British Colony of Kenya, a community of British colonials living in the Wanjohi Valley, near the Aberdare Mountains. This enclave had become notorious among socialites in Great Britain for being a paradise for all those seeking a hedonistic lifestyle, including drugs, alcohol and sexual promiscuity. Noticing that Alice had become restless, Frédéric decided to distract her and agreed to the trip.[25][26]

In the Happy Valley, the de Janzés were neighbours to the Errolls. Frédéric Comte de Janzé documented his time in Happy Valley and all the eccentric personalities he met there in his book, Vertical Land, which was published in 1928. The Comte provided several non-eponymous references to members of the Happy Valley set, including a psychological portrait of his wife that alludes to her suicidal tendencies:

| “ | Wide eyes so calm, short slick hair, full red lips, a body to desire. The powerful hands clutch and wave along the mandolin and the crooning somnolent melody breaks; her throat trembles and her gleaming shoulders droop. That weird soul of mixtures is at the door! her cruelty and lascivious thoughts clutch the thick lips on close white teeth. She holds us with her song, and her body sways towards ours. No man will touch her exclusive soul, shadowy with memories, unstable, suicidal.[27] | ” |

Even among the scandalous residents of Happy Valley, Alice, who was soon known as "the wicked Madonna",[28] caused a sensation with her beauty, sarcastic sense of humour, and wild and unpredictable mood swings. She was known for speaking passionately about animal rights as well as playing the ukulele,[29] and soon she began an affair with Lord Erroll, openly sharing him with Idina.[30][31]

Alice and Frédéric later returned to Happy Valley in 1926. While Frédéric distracted himself with lion hunting, Alice began another love affair, this time with British nobleman Raymond Vincent de Trafford (28 January 1900 – 14 May 1971), son of Sir Humphrey de Trafford, 3rd Baronet. Alice's infatuation with de Trafford was so great that at some point the couple attempted to elope, although they promptly returned.[32] Frédéric was aware of his wife's open infidelity, but did not become preoccupied by it,[29] although years later he would refer to the love triangle with de Trafford as "the infernal triangle".[33]

That autumn, in an attempt to save his marriage, Frédéric returned to Paris with Alice; he was unsuccessful. Alice visited Frédéric's mother: revealing that she was in love with de Trafford, she asked her help in obtaining a divorce. Her mother-in-law advised her to think of her two daughters and do nothing she might later regret. Alice soon returned to Kenya and her lover.[22] Hoping to keep Alice's extramarital affair from becoming a scandal, her mother-in-law loaned Alice a furnished flat in a quiet street in Paris to use as a "love nest" with de Trafford.[34] Under pressure by his family, Frédéric quickly sued for divorce.[35]

1927: The Gare du Nord shooting incident

On the morning of 25 March 1927, Alice awoke in her Paris home feeling extremely agitated, according to the later testimony of her maid.[36] That afternoon, when Alice and Raymond de Trafford met, he informed Alice that he would not be able to marry her as his strict Catholic family had threatened to disinherit him if he followed through with the plan.[37][38] The couple later visited a sporting equipment shop together, where Alice bought a gold-mounted, pearl-handled revolver.[22][32]

At the Gare du Nord a few hours later, as de Trafford was bidding farewell to her in his train compartment before he left for London by an express boat train, she pulled the revolver from her purse and shot him in the stomach, puncturing his lung.[32][39] She then shot herself in the stomach. The train conductor reported that when he opened the compartment door, Alice gasped "I did it" and then collapsed.[22]

De Trafford spent several days in a hospital in critical condition. Alice is reported to have screamed "But he must live! I want him to live!"[9] when she heard the news that de Trafford was too seriously wounded to survive. Her own wound was initially overlooked by doctors during the confusion. Despite initial reports that spoke of her also being gravely injured,[40][41] her wounds were quite superficial. One journalist reported that "she had shot herself very gently".[9] Both Alice and de Trafford were transferred to the Laboisiere hospital. Relatives of Alice rushed to the hospital and attempted to have her transferred to a private clinic, but were stopped by the gendarmes because the countess was technically under arrest.[42]

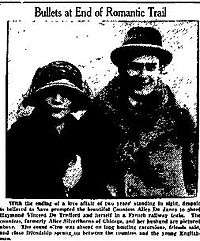

The incident made headlines all over the world.[38][43][44][45] Some confusion was caused when five British newspapers, Western Mail, The Manchester Guardian, The Liverpool Daily Courier, The Liverpool Evening Express and Sheffield Daily Telegraph, illustrated their reports of the shooting incident with pictures not of Alice, but of her sister-in-law Vicomtesse Phillis Meeta de Janzé. The vicountess promptly sued them for libel and received a settlement.[46]

In an attempt to minimize the situation, a statement was released to the press by Alice's family, assuring the public that there was nothing in the double shooting that "casts discredit upon the names of Armour and Silverthorne, which have been honored in America many generations, nor anything which could induce a French jury to render a verdict of conviction".[47] Her aunt Mrs. George Silverthorne told a reporter: "It cannot be Alice. She and her husband were so happy together, and such a thing would be impossible. There must be some mistake".[20]

Alice claimed to feel regret about shooting de Trafford, who was said to be on the brink of death,[40] but did not offer an explanation, telling a police official who was permitted to see her: "I decided to shoot him just as the train was leaving. Why is my own secret. Don't ask me."[48] De Trafford finally regained consciousness and made a brief statement. In an effort to protect Alice, he explained: "Why, Madame attempted suicide. I tried to stop her and the weapon was accidentally discharged. A deplorable accident, surely... but yet, an accident!" before lapsing into unconsciousness again.[39] De Janzé's condition quickly improved and she was first able to talk with relatives on 30 March.[49][50] She officially confessed to the shootings in a signed statement on 2 April, in which she admitted to having attempted suicide numerous times in her life, declaring: "I wanted to kill myself, for I have always had ideas of suicide. From time to time, and without reason, I have wanted to die".[51]

Trial and penalty

On 5 April, Alice de Janzé was officially charged with attempted murder with premeditation.[52][53] On 8 April, she made an official declaration in which she stated she originally only planned suicide when she bought the revolver, but eventually also fired at de Trafford because of anguish at parting from him.[54] In her official declaration to Judge Banquart, who was charged with investigating the case, she stated:

| “ | I met Raymond in Kenya colony, East Africa and became his mistress. It was agreed that I would obtain a divorce to marry him. But gradually he withdrew from the bargain and came to see me in Paris on March 25 to announce that his family was opposed to the match. I already had suffered from the great deception, but when he refused my imploring that he remain with me longer I immediately determined on suicide. Then we took a last luncheon together and for the moment forgot the mental anguish. Afterward he said he would accompany me to shopping and I took him to an armorer's stone, where I bought a revolver and cartridges wrapped separately. Raymond's phlegmatic English type suspected nothing in this incident, evidently thinking that I was doing an errand for my husband. [...] In the station washroom, I had an opportunity to load the weapon, which I still intended only to use on myself, then rejoined him on a compartment of the London express. It was during the anguish of the last moment's separation as we embraced that I suddenly acted on impulse. Slipping the revolver between us, I fired upon him, then upon myself.[55] | ” |

On 9 April, de Trafford returned to London by a special aeroplane, declaring to French authorities that he did not wish to take any action against Alice, although he would return to Paris if his testimony was needed.[56] Meanwhile, de Janzé was held in Saint Lazare, a prison for women.[57][58][59] Her cell, No. 12, had hosted several notorious female criminals in the past, including Mata Hari, Marguerite Steinheil and Henriette Caillaux.[60][61][62] After she made a formal demand for release on bail, she was temporarily freed by the police pending her recovery on 20 May.[63][64] She eventually described what happened in the train station:

| “ | ... The whistle of London Express blew, and I realized that he was going away from Paris – and from me forever – I suddenly changed my mind and resolved to take him away with me into the Great Beyond. Slowly – very slowly – I loosened my grip around his neck, placed the revolver between our two bodies, and, as the train started, fired twice – into his chest and my own body.[61] | ” |

Thanks to the intervention of her aunt, Mrs. Francis May, Alice then vanished from the public eye, hidden in a nursing home close to Paris in preparation for the impending trial. Her lawyers attempted, without success, to have the charges against her dismissed.[65] She was tried by the Paris Tribunal on 23 December 1927,[66] but only on the charge of assault, after her celebrated advocate, René Mettetal,[37] convinced the examining magistrate that she was mentally irresponsible at the time she shot de Trafford.[67][68] When de Trafford was asked if he wanted to press charges against the countess, he expressed surprise and annoyance at the idea, claiming that his wounding was an accident that he himself caused:[69]

| “ | As we were about to part – she was kissing me – I told her that I loved her, and again whispered to her not to take my decision as irrevocable. I even told her that we would meet again. As she was leaving me she attempted suicide. But a movement on my part caused the weapon to be deflected. I am sure that she did not intentionally fire at me. The accident was due to my imprudence.[61] | ” |

Alice's defense lawyer pleaded that the countess' chronic melancholy and tuberculosis had "deadened her intelligence".[69] He also read a letter from her childhood friend, American heiress Mary Landon Baker, in which Baker claimed that Alice suffered from extreme melancholia and that she had attempted suicide a total of four times throughout her life.[69] When asked why she took the gun with her to the railway station, Alice replied: "To kill myself. And I nearly succeeded. Didn't I shoot myself in the stomach, like poor Raymond?"[9] She also made her plea that she be acquitted so as to not disgrace the family name of the de Janzé.[9]

Eventually, Alice received a suspended sentence of six months in prison and a fine of 100 francs (approximately 4 U.S. dollars) by the Paris Correctional Court,[70] who rebuked de Trafford for his failure to deliver his promise to marry her, out of fear of losing the family allowance.[39][71] Although it was criticized by some newspapers,[39] this lenient decision may have been influenced by the revelation concerning Alice's frequent suicide attempts, de Trafford's taking responsibility for her state of mind,[72] and the public's sympathetic view of her as the tragic victim of a true crime of passion. Even the prosecuting attorney insisted upon leniency and declared that "I should not like to bear de Trafford's responsibility for a broken heart and a disrupted home".[72]

Under the First Offenders Act, Alice was immediately released,[73] and on 13 April 1929 she received a full presidential pardon from Gaston Doumergue, the president of the French Republic,[74][75] so that even the fine she had been forced to pay was returned to her by the court.[22] The request for the pardon was partially made to avoid any commercial repercussions the conviction might cause.[76]

In the wake of the shooting scandal, a divorce was granted to Frédéric de Janzé, on the grounds of desertion, by the Paris Tribunal on 15 June 1927.[65][77] While no mention was made of the Gare du Nord episode, Alice was to receive no alimony and Frédéric was granted custody of their two children.[22][78]

That December, Alice shocked both the count and the newspapers when she declared that she would remarry her husband for "the sake of the children";[79] she later retracted her statement.[9] The civil divorce was followed by an annulment of the marriage by the Vatican on 26 July 1928;[80][81] Frédéric's attorneys then warned every newspaper in England never to refer to Alice as Countess de Janzé again.[22] Frédéric died on 24 December 1933, in Baltimore of septicaemia.[82]

1928–1941: Second marriage, divorce and return to Kenya

Following the public ordeal, de Trafford advised Alice against returning to London for a while.[9] In early 1928, she returned to Kenya, but, in light of her public scandal, was soon ordered by the Government House to leave the country as an "undesirable alien".[83] In the following weeks, until she could properly organize her departure and wanting a relatively peaceful place where she could rest after the ordeal, she stayed for a while at the house of writer Karen Blixen, a good friend of Lord Erroll.[84] She also resumed her affair with the Earl.[9][83] Months later, living in Paris and growing indignant about the rumours, she publicly refuted that she had been asked to leave Kenya.[85] It was not until years later that Alice was able to return, thanks to the intervention of both de Janzé and de Trafford, who convinced the Kenyan Government to re-admit her.[9]

Around this time, Alice caused a new sensation when it was revealed she had resumed her love affair with de Trafford, the man she had almost killed. A rumor that the couple would soon have a quiet wedding in Paris was first circulated in May 1927,[57] then in September of that same year[86] and later in January 1928.[87] Alice's lawyer denied any such plans, and no wedding took place.[88] The rumor surfaced again in April 1930.[89] Ultimately, the couple married on 22 February 1932 in Neuilly-sur-Seine[90] and spoke of buying a house in London.[61] Alice commented on her affair with de Trafford: "We were deeply in love. It was arranged that we should marry".,[91] although it has been suggested that Alice literally pursued de Trafford for three years before she finally got him to marry her.[39]

During this time Alice, who now had severe financial reversals, took over the management of a gown shop in Paris under the firm name of "Gloria Bocher", but soon lost both interest and money in the venture.[9][39] Her marriage also rapidly collapsed, ending only three months after the wedding[92] when the couple got into a heated argument in the compartment of an English railroad train over their honeymoon destination. Alice confided to de Trafford that she had purchased the cottage in Happy Valley where they used to rendezvous at the start of their affair,[22] deciding that it would be perfect for their honeymoon. The idea that did not appeal to her new husband; during the course of the argument, Alice absent-mindedly reached into her purse, prompting a terrified de Trafford to flee, fearing a new murder attempt. Alice later claimed she had no pistol in her purse, nor had she the intention of shooting him, but instead wanted to powder her nose.[39]

Alice officially sought a divorce in November 1932, charging Raymond, who had fled to Australia, with cruelty and desertion.[79][93] It took her two years to obtain his signature, and the divorce procedure was reported to begin on September 1934, but did not go forward.[79] Alice may have changed her mind, but she again officially filed for divorce on May 1937,[94] winning an uncontested suit and a grant of decree nisi on the grounds of adultery with an unnamed correspondent at a London hotel.[39][79][95]

Following the divorce, Alice considered permanently returning to Chicago, but friends advised her against it, pointing out how the shooting scandal had made her a "marked woman" in her native land.[9] Accepting her notoriety, Alice returned to the world of 'Happy Valley', where she permanently settled in the large farmhouse she had previously bought in Gilgil, located on the banks of River Wanjohi.[39] She spent the following years reading and taking care of her animals, which included lions, panthers and antelopes. She also became heavily addicted to drugs, particularly morphine.[96] She was avoided by certain members of the community due to her rapid mood swings and the shooting incident; her friend, aviator Beryl Markham, later disclosed: "Loneliness fixed Alice. Everyone was frightened of her".[97]

Alice now only rarely visited her children in France. Years later, Nolwén would state that she did not feel bitterness or hostility for her mother during their brief meetings, but would actually be fascinated by this virtually unknown woman who brought with her an air of mystique, owing to her permanent stay in Africa.[98]

1941: The Lord Erroll murder

On 24 January 1941, Lord Erroll was found shot to death in his car, at an intersection outside Nairobi. Errol's serial philandering contributed to the persistent rumor that the perpetrator was a woman.[99] Police duly interrogated all of Erroll's closest acquaintances, including Alice. Although she had an alibi because she had spent an intimate night with Dickie Pembroke, another Happy Valley resident, due to her drug habits, her romantic attachment to Errol, and her previous attempt to kill a paramour,[100] she was immediately regarded as the prime suspect among the white community of Happy Valley. It was also rumoured that Alice had attempted suicide on hearing the news of Erroll's death.[31]

On the morning after Erroll's body was discovered, de Janzé went to the morgue with a friend to see his body. According to eyewitnesses, Alice stunned those in attendance by leaving a tree branch on Erroll's corpse, and whispering the words: "Now you are mine forever". Eyewitness and close friend Julian Lezzard suspected that Alice was the murderer, since it fitted with her morbid preoccupations;[97] it was even rumoured that Alice herself had admitted to the killing.[101] In his investigative book, White Mischief, journalist James Fox mentions a suspicious incident regarding Alice and her possible connection to the crime. A few months after the murder, Alice went away for a few days and asked a neighbour to look after her house. In her absence, one of Alice's houseboys came to the neighbour, and produced a revolver, which he claimed he had found by a bridge, under a pile of stones on Alice's land.[102]

In March 1941, British aristocrat Sir Henry John "Jock" Delves Broughton was officially charged with Lord Erroll's murder.[103] Delves Broughton had been aware of a passionate love affair between his young wife, Diana, and Erroll, in the months before his murder.[104][105] De Janzé paid regular visits to Delves Broughton in prison, and, with her friend Idina, the late Errol's first wife, attended every day of the trial.[31] In July 1941, Delves Broughton was acquitted due to lack of evidence.[106]

Paul Spicer theorizes that Alice was the real murderer of Lord Erroll, based on several letters that Alice's personal doctor and former lover, William Boyle, discovered in her house on the day of her death, and later handed over to the police. Decades later, Boyle's daughter revealed that one letter contained her full confession to the murder of Lord Erroll, a fact that Boyle revealed to his family.[107]

Death

In August 1941, after being diagnosed with uterine cancer, Alice underwent a hysterectomy.[108] On 23 September, she attempted suicide by taking an overdose of pentobarbital. When her friend, Patricia Bowles, discovered her, she had already marked every piece of furniture with the name of the friend who would inherit it. Bowles rescued Alice by calling a doctor to pump her stomach.[108]

A week later, on 30 September, two days after turning 42, she finally succeeded in ending her life. A servant found her dead on her bed from a self-inflicted gunshot wound, from the same weapon she had once used on Raymond and herself.[22][109] Michael Kilian, who has written extensively about Alice's life, believes that she chose suicide because she became depressed about her aging appearance and loss of looks.[110] It was not the first suicide in her family: her cousin, John Hellyer Silverthorne had also committed suicide by gunshot in his home in Chicago in 1933, at the age of 26.[111]

Alice left three suicide notes, one addressed to the police, one to her daughters and one to Dickie Pembroke. The content of the letters was never publicly disclosed, fueling rumours that they containing revelations into the Errol murder. A government official, summoned to examine her possessions, was reportedly dumbfounded when he came across the letters. After a long, secret meeting among officials, it was decided that the content of her papers and letters would not be made public.[9] What did become known is that she had requested that her friends hold a cocktail party on her grave.[108]

On 21 January 1942, following an inquest in Nairobi, her death was officially ruled a suicide; the finding was delayed due to the difficulty in obtaining evidence. The coroner also concluded there was no sign of insanity,[112] but he further fuelled the conspiracy theories by stating that the content of Alice's letters were such as to merit their being destroyed, because they constituted damaging revelations of a social and political nature.[9]

Legacy

Writer Joseph Broccoli conjectures that Alice de Janzé and the 1927 shooting served as a source of inspiration for Maria Wallis and the shooting incident in F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel Tender Is the Night (1934),[113][114]

In 1982, Alice de Janzé's life was prominently featured in the investigative non-fiction book White Mischief by journalist James Fox, which examined the events surrounding the murder of Lord Erroll, the Happy Valley set, and their notorious life before and after the event. In 1988, the book was made into an eponymous film, directed by Michael Radford, in which Alice de Janzé was portrayed by British actress Sarah Miles.[115] Radford was reportedly drawn to the story primarily due to an incident attributed to Alice, in which she had once flung open the shutters of her window in her house in Kenya and remarked: "Oh, God. Not another fucking beautiful day." Radford incorporated this scene into the film.[116]

The film adaptation makes much of de Janzé's eccentricities, including scenes in which she watches a polo match with a snake twined around her shoulders, or doses herself with a syringe of morphine in the ladies' toilet.[117] In 1988, Miles stated at the Cannes Film Festival that as an actress de Janzé was a difficult character for her to portray. When she first arrived in Kenya, Miles sought people who knew Alice but was unable to learn anything substantial due to those acquaintances' confused perceptions of de Janzé; some were even uncertain as to her true nationality.[118]

Michael Kilian makes reference to Alice in his novel of historical fiction Dance on a Sinking Ship (1988), in which a character boasts of having taken her virginity,[119] and included her as a character in another novel of historical fiction Sinful Safari (2003) in which various members of the Happy Valley set, including Alice, are suspects in a fictional murder case in 1920s Kenya.[120] Similarly, Paul Di Filippo based Alice and several other members of the Happy Valley set as the protagonists in his fictional story "The Happy Valley at the End of the World", part of his collection, Lost Pages (1998).[121] Her character also briefly appears in another novel of historical fiction, Stephen Maitland-Lewis' Hero on Three Continents (2004), in which she is comically depicted recounting how she once shot one of her former husbands but "sadly botched it up".[122]

The music band Building released a song in their album Second Building that is titled Alice de Janze and is inspired by the story of Alice, making reference to her suicide with the lyric "you died too young".[123]

Fashion designer Edward Finney's Spring/Summer Collection 2012 was inspired by the life of Alice de Janze.[124]

Descendants and relatives

- Alice's oldest daughter, Nolwén, became a fashion designer and was president of the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers in the 1950s.[125] She had two children, a daughter Angelique and a son Frederic Armand-Delille. In 1981, Angelique worked as picture assistant for the film Quartet. In 1977, Nolwén married the well known art historian Kenneth Clark. He died in 1983. Nolwén died on 7 March 1989 in France at the age of 67 after undergoing heart surgery.

- Her second daughter, Paola, died in Normandy, close to the family property, in Dieppe on 24 December 2006 at the age of 82. She married three times and had four children: Guillaume de Rougemont (1945) Arthur Hayden (1947) and Moya Hayden(1950). In 1955 she married amateur rider John Ciechanowski and had a son (Alexander Ciechanowski 1956) with him.[126]

References

- 1 2 Reed, Frank Fremont (1982). History of the Silverthorn Family, Vol. 4,p. 550. Chicago: DuBane's Print Shop. Her birth and death date can also be found at http://www.ancestry.com/trees/awt/main.aspx. (free registration required)

- ↑ Chapin, Gilbert Warren (1924). The Chapin Book of Genealogical Data: With Brief Biographical Sketches, of the Descendants of Deacon Samuel Chapin, Vol. 2. Chapin Family Association, p. 1795

- 1 2 Reed, Frank Fremont (1982). The History of the Silverthorn Family, Vol. 4. Chicago: DuBane's Print Shop, p. 434

- 1 2 3 4 Fox James (1983). White Mischief. Random House, p. 39

- ↑ The New York Times, November 18, 1897. "Mrs. Chapin Leaves $500,000", p. 1

- ↑ Illinois Statewide Marriage Index, 1763–1900 Archived 18 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, 29 May 1892. "Month of Weddings", p. 10

- 1 2 3 Chicago Tribune, Sunday Magazine, 26 May 1996. "Hey Lady! Britain's Beleaguered Princess Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet – Chicago's Rendition", p. 14

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The Milwaukee Sentinel, June 27, 1948. Coughlin, Gene. "Battered Brides: Unhappy Hunt of the Golden Girl", p. 32

- 1 2 The Times Online, The Sunday Times, May 2, 2010. Wilson, Frances. "The Tempress: The Scandalous Life of Alice, Countess de Janze Review".

- 1 2 3 4 Fox, James (1982). White Mischief. Random House, p. 40

- ↑ Reed, Frank Fremont (1982). History of the Silverthorn Family, Vol. 4. Chicago: DuBane's Print Shop, p. 562

- ↑ Telegraph. April 27, 2010. Grice, Elizabeth. "Is This the Happy Valley Murderer?"

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, 1 June 1988. Kilian, Michael. "Making Mischief Take It from the Brits: After Decades of Civility, America is Due for Some Decadence", p. 10

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, 16 September 1987. Kilian, Michael. "Shrink to Fit? What Ever Happened to Good, Old-Fashioned Lunacy? Now, Even New Yorkers are Buying into the Therapy Fad", p. 6

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, Sunday Magazine, 20 August 1986. Kilian, Michael. "Unhappy Endings When Chicago and Europe Play at Love, the Consequences Can be Disastrous", p. 14

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, 1 October 1941. "Chicago Tragic Countess Slain in East Africa", p. 1

- ↑ The New York Times, 16 June 1927. "De Janzés Divorced by Paris Tribunal", p. 56

- ↑ Fox, James (1983). White Mischief. Random House, p. 35

- 1 2 3 The New York Times, 27 March 1927. "Chicago Relatives Amazed", p. 9

- ↑ "Alice Silverthorne is Vicomte's Bride", The New York Times, 21 September 1921

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 The Milwaukee Sentinel, October 26, 1941. "Killed Herself Where She Lost Her Honor 15 Years Before", P. 30

- ↑ Los Angeles Times, 20 April 1922. "Wedding of Mary Baker is Delayed"

- ↑ Marnham, Patrick. "Dirty Work at the Crossroads", The Spectator, March 18, 2000

- ↑ Trzebinski, Erroll (2000). The Life and Death of Lord Erroll, p. 76. Fourth Estate

- ↑ "She Loved Him, Shot Him, Married Him, Divorced Him", The Oakland Tribune, 12 December 1937

- ↑ De Janzé, Frédéric.Vertical Land. London: Duckworth Press, 1928, Chapter VIII

- ↑ Morrow, Anne. Picnic in a Foreign Land: The Eccentric Lives of the Anglo-Irish. Grafton: 2003, p. 54 ISBN 978-0-246-13204-8

- 1 2 White Mischief, p. 41

- ↑ Osborne, Frances (2009). The Bolter, p. 132. Knopf

- 1 2 3 Osborne, Frances. "Sex Games and Murder in Idina's Happy Valley", Times Online, May 4, 2008

- 1 2 3 White Mischief, p. 42

- ↑ The Life and Death of Lord Erroll: The Truth Behind the Happy Valley Murder, p. 86

- ↑ "Chicago Countess and Dashing Briton She Shot Are Near Death in Paris", Chicago Tribune, 28 March 1927

- ↑ "Paris Shocked Over Countess Love Tragedy", The Miami News, May 28, 1927

- ↑ The Montreal Gazette, March 28, 1927. "Countess Shot Englishman and Self in Paris", p. 13

- 1 2 "Used Pistol Bullets Instead of Cupid Darts", The Milwaukee Sentinel, 18 February 1933

- 1 2 "First Shot Lover and then Herself", Ottawa Citizen, March 28, 1927

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Fined the Countess 4$ For Shooting Her Boy-Friend", The Delmarvia Star, January 28, 1928

- 1 2 "Countess Reticent With Victim Dying", The New York Times, 28 March 1927

- ↑ "Countess de Janzé Weaker", Hartford Courant, 29 May 1927

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, 7 April 1927

- ↑ "American Countess Shoots Self After Woonding Admirer", Washington Post, 27 March 1927.

- ↑ "Society Girl Shoots Lover and Herself", The Hartford Courant, 27 March 1927

- ↑ "Paris Shooting Led to Despair", Los Angeles Times, 28 May 1927

- ↑ The Times, 1 June 1927

- ↑ The Montreal Gazette, March 28, 1927. "Countess Shoots Englishman and Self in Paris", p. 1

- ↑ "Countess Near Death of Wound", The Pittsburgh Press, March 28, 1927

- ↑ "Countess Improves, Victim Near Death", The Washington Post, 31 March 1927

- ↑ "Countess Janzé Better", The New York Times, 31 March 1927

- ↑ "Countess Gives First Story of Shooting Lover", Chicago Daily Tribune, 3 April 1927

- ↑ "Countess Is Accused of Attempted Murder", New York Times, 5 April 1927

- ↑ "Serve Countess with Homicide Attempt Papers", Chicago Tribune, 5 April 1927

- ↑ "Countess Explains Double Shooting", The New York Times, 9 April 1927

- ↑ The Montreal Gazette, April 9, 1927. "Countess de Janzé Makes Declaration", p. 11

- ↑ "Plane Trip Made by de Trafford", The Miami News, April 18, 1927

- 1 2 Chicago Tribune, 8 May 1927

- ↑ "Lazare Day", Time, August 22, 1932 Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Barrow, Andrew (1979). Gossip: A History of High Society from 1920 to 1970, p. 33. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan.

- ↑ Secrest, Meryle (1985). Kenneth Clark: A Biography, p. 143. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- 1 2 3 4 The Best Jail Cell in Paris

- ↑ "As the Fabulous French Women's Prison Falls After 14 Years, Comes the First Look-in on its Million Secrets", The Miami News, June 19, 1932

- ↑ "De Janzé Asks Bail", Herald-Journal, May 22, 1927

- ↑ "Countess de Janzé is Temporarily Freed", The New York Times, 20 May 1927

- 1 2 "Count de Janzé Divorces Wife, Who Shot Man", Chicago Tribune, 16 June 1927

- ↑ "Will Try Countess Today", The New York Times, 23 December 1927

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, 17 December 1927

- ↑ "Alice de Janzé to Go on Trial in Paris Tomorrow", Chicago Tribune, 22 December 1927

- 1 2 3 "Alice de Janzé Kept from Cell by Man She Shot", Chicago Daily Tribune, 24 December 1927

- ↑ "Chicago Countess Who Shot Lover and Herself Gets Off With a 4$ in French Court", The New York Times, 24 December 1927

- ↑ Gossip: A History of High Society from 1920 to 1970, p. 33

- 1 2 "Countess de Luxe", Palm Beach Daily News, December 27, 1927

- ↑ Gossip: A History of High Society from 1920 to 1970, p. 36

- ↑ "Frees Countess de Janzé", The New York Times, 14 April 1929

- ↑ The Evening Independent, April 13, 1929

- ↑ "American Countess is Pardoned in Shooting", The Lima News, 13 April 1929

- ↑ "De Janzes Divorced by Paris Tribunal", New York Times, 16 June 1927

- ↑ "Americans Win Paris Divorces", Los Angeles Times, 16 June 1927

- 1 2 3 4 "Chased Him 3 Years to Marry – Chased Him 3 Years to Divorce", The Milwaukee Sentinel, September 16, 1934

- ↑ "Milestone" Time, August 6, 1928

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, 26 July 1928

- ↑ "Com. F. Janzé, Sportsman, Dead", The New York Times, 25 December 1933

- 1 2 White Mischief, p. 47

- ↑ L'Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, issue 643, June 2006.

- ↑ "Countess de Janzé Says She Was Not Ousted From Africa", Chicago Tribune, 8 May 1928

- ↑ "Shot Wins Hubby", The Charleston Gazette, 15 September 1927

- ↑ "American May Marry Britisher She Shot", The Pittsburgh Press, January 30, 1928

- ↑ "Lawyer Denies Alice de Janzé Plans to Marry", Chicago Daily Tribune, 30 January 1928

- ↑ Syracuse Herald, 7 April 1930

- ↑ "Weds Man She Shot", The Evening Independent, February 20, 1932

- ↑ "News and Views of Recent Events in the British Isles", The Ottawa Citizen, p. 21, June 23, 1939

- ↑ Osborne, Frances (2009). The Bolter, p. 189. Knopf

- ↑ "Asks Paris Divorce from de Trafford", The New York Times, 19 November 1932

- ↑ "Divorce Suit Filed in London", Chicago Daily Tribune, 22 May 1937

- ↑ "Decree Nisi Granted", The Montreal Gazette, October 26, 1937

- ↑ Osborne, Frances (2009). The Bolter, p. 213. Knopf

- 1 2 White Mischief, p. 193

- ↑ White Mischief, p. 44

- ↑ The Life and Death of Lord Erroll, p. 237

- ↑ White Mischief, p. 144, 159–160

- ↑ Evans, Collins (2003). A Question of Evidence: The Casebook of Great Forensic Controversies, from Napoleon to O.J., p. 88. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-46268-2

- ↑ White Mischief, p. 144

- ↑ "Leader of British Society Named on Murder Charge", The Pittsburgh Press, p. 18, March 11, 1941

- ↑ "Sir D. Broughton's Trial is Adjourned to April 7", Ottawa Citizen, p. 9, March 25, 1941

- ↑ "Nairobi Murder Trial", The Glasgow Herald, p. 5, June 10, 1941

- ↑ "Broughton Acquitted of Murder Charge", The Daily Times, Beaver and Rochester, July 2, 1941

- ↑ Daily Mail. April 23, 2010. Colin, Tasha. "The White Mischief Murderess: 70-Year Long Mystery Over Murder in Debauched Happy Valley Set Finally Solved

- 1 2 3 White Mischief, p. 216

- ↑ "An Ex-Countess Shot Found Dead", The New York Times, 1 October 1941

- ↑ Kilian, Michael. "Vainest Woman Met Museum of Art Exhibit Shows 'La Divine Comtesse' in her Glory", Chicago Tribune, 2 November 2000

- ↑ "Young Society Husband Kills Himself in Home", Chicago Tribune, 24 January 1933

- ↑ "Verdict of Suicide Returned in Death of Armour Niece", The Milwaukee Journal, January 21, 1942

- ↑ Bruccoli, Joseph Matthew & Baughman, Judith S. (1996). Reader's Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald's Tender Is the Night. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, p. 91. ISBN 1-57003-078-2

- ↑ Tate, Jo Mary (2007). F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Lirerary Reference to his Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, Inc, p. 224

- ↑ Internet Movie Database entry for White Mischief

- ↑ The Washington Post, 23 May 1988. Battiata, Mary. "John Hurt into Africa; After Making Mischief in Kenya, The Actor Enjoys His New Domicile"

- ↑ The New York Times, May 22, 1988. Gross, John. "Two New Movies Suggest that Shock Tactics are Best Muted In a Work of Art"

- ↑ The New York Times, April 29, 1988. van Gelder, Lawrence. "At the Movies"

- ↑ Kilian, Michael (1989). Dance on a Sinking Ship. Bantam, p. 158.

- ↑ Kilian, Michael (2003). Sinful Safari. Berkley, p. 190

- ↑ Di Filippo, Paul (1998). Lost Pages. Four Walls Eight Windows, p. 56

- ↑ Maitland-Lewis, Stephen (2004). Hero on Three Continents. Xlibris Corporation, p. 210

- ↑ Alice de Janze. From album Second Story by Building.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-22. Interview with Edward Finney at beatreview.com

- ↑ "Nolwen de Janze Clark, Fashion Designer, 65". New York Times. 9 March 1989. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ Obituary of John Ciechanowski