Zorba the Greek

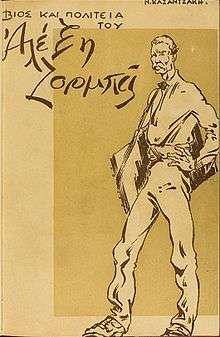

First edition | |

| Author | Nikos Kazantzakis |

|---|---|

| Original title | Βίος και Πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά (Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas) |

| Country | Greece |

| Language | Greek |

| Published | 1946 (Greek) |

| OCLC | 35223018 |

| 889/.332 20 | |

| LC Class | PA5610.K39 V5613 1996 |

Zorba the Greek (Βίος και Πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά Víos ke Politía tou Aléxi Zorbá, Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas) is a novel written by the Cretan author Nikos Kazantzakis, first published in 1946. It is the tale of a young Greek intellectual who ventures to escape his bookish life with the aid of the boisterous and mysterious Alexis Zorba. The novel was adapted into a successful 1964 film of the same name by Michael Cacoyannis as well as a 1968 musical, Zorba.

Plot

The book opens in a café in Piraeus, just before dawn on a gusty autumn morning. The year is most likely 1916. The narrator, a young Greek intellectual, resolves to set aside his books for a few months after being stung by the parting words of a friend, Stavridakis, who has left for the Russian Caucasus to help some Pontic Greeks (in that region often referred to as Caucasus Greeks) who are being persecuted. He sets off for Crete to re-open a disused lignite mine and immerse himself in the world of peasants and working-class people.

He is about to begin reading his copy of Dante's Divine Comedy when he feels he is being watched; he turns around and sees a man of around sixty peering at him through the glass door. The man enters and immediately approaches him to ask for work. He claims expertise as a chef, a miner, and player of the santuri, or cimbalom, and introduces himself as Alexis Zorba, a Greek born in Romania. The narrator is fascinated by Zorba's lascivious opinions and expressive manner and decides to employ him as a foreman. On their way to Crete, they talk on a great number of subjects, and Zorba's soliloquies set the tone for a large part of the book.

On arrival, they reject the hospitality of Anagnostis and Kondomanolious the café-owner, and on Zorba's suggestion make their way to Madame Hortense's hotel, which is nothing more than a row of old bathing-huts. They are forced by circumstances to share a bathing-hut. The narrator spends Sunday roaming the island, the landscape of which reminds him of "good prose, carefully ordered, sober… powerful and restrained" and reads Dante. On returning to the hotel for dinner, the pair invite Madame Hortense to their table and get her to talk about her past as a courtesan. Zorba gives her the pet-name "Bouboulina" (likely inspired by the Greek heroine).

The next day, the mine opens and work begins. The narrator, who has socialist ideals, attempts to get to know the workers, but Zorba warns him to keep his distance: "Man is a brute.... If you're cruel to him, he respects and fears you. If you're kind to him, he plucks your eyes out." Zorba himself plunges into the work, which is characteristic of his overall attitude, which is one of being absorbed in whatever one is doing or whomever one is with at that moment. Quite frequently Zorba works long hours and requests not to be interrupted while working. The narrator and Zorba have a great many lengthy conversations, about a variety of things, from life to religion, each other's past and how they came to be where they are now, and the narrator learns a great deal about humanity from Zorba that he otherwise had not gleaned from his life of books and paper.

The narrator absorbs a new zest for life from his experiences with Zorba and the other people around him, but reversal and tragedy mark his stay on Crete. His one-night stand with a beautiful passionate widow is followed by her public decapitation. Alienated by the villagers' harshness and amorality, he eventually returns to the mainland once his and Zorba's ventures are completely financially spent. Having overcome one of his own demons (such as his internal "no," which the narrator equates with the Buddha, whose teachings he has been studying and about whom he has been writing for much of the narrative, and who he also equates with "the void") and having a sense that he is needed elsewhere (near the end of the novel, the narrator has a premonition of the death of his old friend Stavridakis, which plays a role in the timing of his departure to the mainland), the narrator takes his leave of Zorba for the mainland, which, despite the lack of any major outward burst of emotionality, is significantly emotionally wrenching for both Zorba and the narrator. It almost goes without saying that the two (the narrator and Zorba) will remember each other for the duration of their natural lives.

The narrator and Zorba never see each other again, although Zorba sends the narrator letters over the years, informing him of his travels and work, and his marriage to a 25-year-old woman. The narrator does not accept Zorba's invitation to visit. Eventually the narrator receives a letter from Zorba's wife, informing him of Zorba's death (which the narrator had a premonition of). Zorba's widow tells the narrator that Zorba's last words were of him, and in accordance with her dead husband's wishes, she wants the narrator to visit her home and take Zorba's santuri.

Characters

- Alexis Zorba (Αλέξης Ζορμπάς), a fictionalized version of the mine worker, George Zorbas (Γιώργης Ζορμπάς, 1867–1941).[1]

References

- ↑ Thomas R. Lindlof, Hollywood under siege

Further reading

- Hnaraki, Maria (2009). "Speaking without words: Zorba's dance" (PDF). Glasnik Etnografskog instituta SANU. 57 (2). doi:10.2298/GEI0902025H.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Zorba the Greek |

- The Nikos Kazantzakis Files (Greek)

- Book review, Time Magazine, April 20, 1953