Alexandra Kollontai

| Alexandra Kollontai | |

|---|---|

Alexandra Kollontai, circa 1900. | |

| Born |

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai 31 March 1872 Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died |

9 March 1952 (aged 79) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation | writer, ambassador |

| Spouse(s) | Vladimir Ludvigovich Kollontai; Pavel Dybenko |

| Children | Mikhail Alekseevich Domontovich |

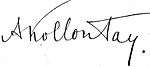

| Signature | |

| |

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai (Russian: Алекса́ндра Миха́йловна Коллонта́й — née Domontovich, Домонто́вич; 31 March [O.S. 19 March] 1872 – 9 March 1952) was a Russian Communist revolutionary, first as a member of the Mensheviks, then from 1915 on as a Bolshevik. In 1923, Kollontai was appointed Soviet Ambassador to Norway, one of the first women to hold such a post.

Biography

Early life

Alexandra Mikhailovna Domontovich was born on 31 March [O.S. 19 March] 1872 in St. Petersburg. Her father, General Mikhail Alekseevich Domontovich, descended from a Ukrainian Cossack family that traced its ancestry back to the 13th century.[1] He served as a cavalry officer in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 and as an advisor to the Russian administration in Bulgaria after the war until 1879. He entertained liberal political views, favoring a constitutional monarchy like that of Great Britain, and in the 1880s had written a study of the Bulgarian war of independence which was confiscated by the Tsarist censors, presumably for showing insufficient Russian nationalist zeal.[2] Alexandra's mother, Alexandra Androvna Masalina-Mravinskaya,[lower-alpha 1] the daughter of a Finnish peasant who had made a fortune selling wood, obtained a divorce from an unhappy arranged first marriage so that she could marry Domontovich, with whom she had fallen in love.[2] Russian opera singer Yevgeniya Mravina (née Mravinskaya) was Kollontai's half-sister via her mother.

The saga of her parents' long and difficult struggle to be together in spite of the norms of society would color and inform Alexandra Kollontai's own views of relationships, sex, and marriage.

Alexandra Mikhailovna – or "Shura" as she was called growing up – was close to her father, with whom she shared an analytical bent and an interest in history and politics.[3] Her relationship with her mother, for whom she was named, was more complex. She later recalled:

My mother and the English nanny who reared me were demanding. There was order in everything: to tidy up toys myself, to lay my underwear on a little chair at night, to wash neatly, to study my lessons on time, to treat the servants with respect. Mama demanded this.[4]

Alexandra was a good student growing up, sharing her father's interest in history, and mastering a range of languages. She spoke French with her mother and sisters, English with her nanny, Finnish with the peasants at a family estate inherited from her maternal grandfather in Kuusa (in Muolaa, Grand Duchy of Finland), and was a student of German.[5] Alexandra sought to continue her schooling at a university, but her mother refused her permission, arguing that women had no real need for higher education, and that impressionable youngsters encountered too many dangerous radical ideas at universities in any event.[6] Instead, Alexandra was to be allowed to take an exam to gain certification as a school teacher before making her way into society to find a husband, as was the custom.[6]

In 1890 or 1891, Alexandra, aged around 19, met her future husband, Vladimir Ludvigovich Kollontai, an engineering student of modest means enrolled at a military institute.[7] Alexandra's mother objected bitterly to the potential union since the young man was so poor, to which her daughter replied that she would work as a teacher to help make ends meet. Her mother bitterly scoffed at the notion:

You work! You, who can't even make up your own bed to look neat and tidy! You, who never picked up a needle! You, who go marching through the house like a princess and never help the servants with their work! You, who are just like your father, going around dreaming and leaving your books on every chair and table in the house![8]

Her parents forbade the relationship and sent Alexandra on a tour of Western Europe in the hope that she would forget Vladimir, but the pair remained committed to one another despite it all and married in 1893.[9] Alexandra became pregnant soon after her marriage and bore a son, Mikhail, in 1894. She devoted her time to reading radical populist and Marxist political literature and writing fiction.[10]

Revolutionary activities

While Kollontai was initially drawn to the populist ideas of a restructuring of society based upon the Mir (peasant commune), effective advocates of such theories in the last decade of the 19th century were few.[11] Marxism, with its emphasis on the enlightenment of factory workers, the revolutionary seizure of power, and the construction of modern industrial society, held sway with Kollontai as with so many of her peers of Russia's radical intelligentsia. Kollontai's first activities were timid and modest, helping out a few hours a week with her sister Zhenia at a library that supported Sunday classes in basic literacy for urban workers, sneaking a few socialist ideas into the lessons.[lower-alpha 2] Through this library Kollontai met Elena Stasova, an activist in the budding Marxist movement in St. Petersburg. Stasova began to use Kollontai as a courier, transporting parcels of illegal writings to unknown individuals, which were delivered upon utterance of a password.[12]

Years later, she wrote about her marriage, "We separated although we were in love because I felt trapped. I was detached, [from Vladimir], because of the revolutionary upsettings rooted in Russia". In 1898 she left little Mikhail with her parents to study economics in Zürich, Switzerland, with Professor Heinrich Herkner. She then paid a visit to England, where she met members of the British Labour Party. She returned to Russia in 1899, at which time she met Vladimir Ilych Ulyanov, a.k.a. Vladimir Lenin.

Kollontai became interested in Marxist ideas while studying the history of working movements in Zürich, under Herkner, later described by her as a Marxist Revisionist.

She became a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, aged 27, in 1899. She was a witness of the popular rising in 1905 known as Bloody Sunday, at Saint Petersburg in front of the Winter Palace.

She went into exile, to Germany, in 1908[13] after publishing "Finland and Socialism", which called on the Finnish people to rise up against oppression within the Russian Empire. She visited England, France, and Germany, and became acquainted with Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

With the onset of World War I in 1914 Kollontai left Germany due to the German social democrats' support of the war. Kollontai was strongly opposed to the war and very outspoken against it. After leaving Germany Kollontai traveled to Denmark, only to discover that the Danish social democrats also supported the war. The next place Kollontai tried to speak and write against the war was Sweden. In Sweden the government imprisoned her for her activities. After her release Kollontai traveled to Norway, where she at last found a socialist community that was receptive to her ideas. Kollontai stayed primarily in Norway until 1917, only traveling internationally to speak about war and politics.[14] In 1917 Kollontai left Norway to return to Russia upon receiving news of Tsar's abdication and the onset of the Russian Revolution.[15]

Political career

At the time of the split in the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party into the Mensheviks under Julius Martov and the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin in 1903, Kollontai did not side with either faction at first, but by 1905 she had sided with the Mensheviks. In 1915, Kollontai officially left the Mensheviks and joined the Bolshevik Party.[16]

After the Bolshevik revolution in October 1917, Kollontai's political career began. She became People's Commissar for Social Welfare. She was the most prominent woman in the Soviet administration and was best known for founding the Zhenotdel or "Women's Department" in 1919 . This organization worked to improve the conditions of women's lives in the Soviet Union, fighting illiteracy and educating women about the new marriage, education, and working laws put in place by the Revolution. As a foremost champion of women's equality like the other Marxists of her time, she opposed the ideology of liberal feminism, which she saw as bourgeois,[17][18] though later feminists have claimed her legacy. The Zhenotdel was eventually closed in 1930. Kollontai also married Pavel Dybenko in 1917.[19]

In the government, Kollontai increasingly became an internal critic of the Communist Party and joined with her friend, Alexander Shlyapnikov, to form a left-wing faction of the party that became known as the Workers' Opposition.[20] However, Lenin managed to dissolve the Workers' Opposition, after which Kollontai was more or less politically sidelined.

Kollontai lacked political influence and was appointed by the Party to various diplomatic positions from the early 1920s, keeping her from playing a leading role in the politics of women's policy in the USSR. In 1923, she was appointed Soviet Ambassador to Norway, becoming the world's second female ambassador in modern times, after Armenia Ambassador to Japan Diana Abgar. She later served as Ambassador to Mexico (1926–27) and Sweden (1930–1945). When she was in Stockholm, the Winter War between Russia and Finland broke out; it has been said that it was largely due to her influence that Sweden remained neutral.[21] After the war, she received Vyacheslav Molotov's praises. During late April 1943, she may have been involved in abortive peace negotiations with Hans Thomsen, her German counterpart in Stockholm.[22] She was also a member of the Soviet delegation to the League of Nations.

Social ideas

Kollontai is known for her advocacy of free love. However, this does not mean that she advocated casual sexual encounters; indeed, she believed that due to the inequality between men and women that persisted under socialism, such encounters would lead to women being exploited, and being left to raise children alone. Instead she believed that true socialism could not be achieved without a radical change in attitudes to sexuality, so that it might be freed from the oppressive norms that she saw as a continuation of bourgeois ideas about property. A common myth describes her as a proponent of the "glass of water" theory of sexuality.[23] The quote "...the satisfaction of one's sexual desires should be as simple as getting a glass of water"[24] is often mistakenly attributed to her.[25] This is likely a distortion of the moment in her short story "Three Generations" when a young female Komsomol member argues that sex "is as meaningless as drinking a glass of vodka [or water, depending on the translation] to quench one's thirst."[26] In number 18 of her Theses on Communist Morality in the Sphere of Marital Relations, Kollontai argued that "...sexuality is a human instinct as natural as hunger or thirst."

Kollontai's views on the role of marriage and the family under Communism were arguably more influential on today's society than her advocacy of "free love." [23] Kollontai believed that, like the state, the family unit would wither away once the second stage of communism became a reality. She viewed marriage and traditional families as legacies of the oppressive, property-rights-based, egoist past. Under Communism, both men and women would work for, and be supported by, society, not their families. Similarly, their children would be wards of, and reared basically by society.

Kollontai admonished men and women to discard their nostalgia for traditional family life. "The worker-mother must learn not to differentiate between yours and mine; she must remember that there are only our children, the children of Russia's communist workers." However, she also praised maternal attachment: "Communist society will take upon itself all the duties involved in the education of the child, but the joys of parenthood will not be taken away from those who are capable of appreciating them."[27]

Death and legacy

Alexandra Kollontai died in Moscow on 9 March 1952, less than a month away from her 80th birthday.

Kollontai was the subject of the 1994 TV film, A Wave of Passion: The Life of Alexandra Kollontai, with Glenda Jackson as the voice of Kollontai. A female Soviet diplomat in the 1930s with unconventional views on sexuality, probably inspired by Kollontai, was played by Greta Garbo in the movie Ninotchka (1939).

The resurgence of radicalism in the 1960s and the growth of the feminist movement in the 1970s spurred a new interest in the life and writings of Alexandra Kollontai in Britain and America. A spate of books and pamphlets were subsequently published by and about Kollontai, including full-length biographies by historians Cathy Porter [28] and Barbara Evans Clements.

Anecdotes

While she was ambassador to Sweden, a stroke made it impossible for her to write; thus, she dictated her memories to the attaché Vladimir Yerofeev, who recorded her anecdotes.[29] One of them is the following: soon after the revolution, she was ambassador in Norway, who had recognized the Soviet Union, but de facto, not de jure; now, the formal recognition was what interested the Soviet authorities. In this delicate situation, came a delegation from Russia to sell a large quantity of timber. The Norwegians offered a very low price; when she noted that the negotiation was at a standstill, she said: "These gentlemen don't have the mandate to accept such a low price; neither have I; but the friendship of Norway is so important for us, that I will pay the difference." The Norwegian delegation retired to consult, after which they said: "We are not so impolite to accept your offer; we accept the Russian price."

Soon after the revolution, while she was a minister in the new revolutionary government, she disappeared for ten days to reunite with Pavel Dybenko. Everybody thought she had been kidnapped by the counterrevolutionaries. When she reappeared, her comrades urged Lenin to gather a soviet to condemn her behavior. Lenin did so, and many people, whom she thought friends, said horrible things about her. At last, Lenin spoke — Lenin always spoke very quickly, but in this case he spoke slowly, giving weight to every word: "I agree with all you said, comrades; I think that Alexandra Michailovna must be punished severely; I propose that she marry Dybenko." Everybody laughed, and the matter was closed. For her, being married with someone with whom she had a briefly passionate encounter was really a punishment;[30] however, soon after the meeting, when she was still in tears, Lenin said to her: "I was speaking in earnest." Thus they married, but the marriage did not last long: their duties as people's commissars tore them apart.

Awards

- Order of Lenin (1933)[31]

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1945)[31]

- Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav (Norwegian highest award at the time)[32]

- Order of the Aztec Eagle (1944)[31][33][lower-alpha 4]

Works

- "The Attitude of the Russian Socialists," The New Review, March 1916, pp. 60–61.

- Red Love. [novel] New York: Seven Arts, 1927.

- Free Love. London: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1932.

- Communism and the Family. Sydney: D. B. Young, n.d. [1970].

- The Autobiography of a Sexually Emancipated Communist Woman. n.c. [New York]: Herder and Herder, n.d. [1971].

- Sexual Relations and the Class Struggle: Love and the New Morality. Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1972.

- Women Workers Struggle for their Rights. Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1973.

- The Workers' Opposition. San Pedro, CA: League for Economic Democracy, 1973.

- International Women's Day. Highland Park, MI: International Socialist Publishing Co., 1974.

- Selected Writings of Alexandra Kollontai. Alix Holt, trans. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1977.

- Love of Worker Bees. [novel] Cathy Porter, trans. London: Virago, 1977 [new translation of Red Love plus 2 short stories]

- A Great Love. [novel] Cathy Porter, trans. London: Virago, 1981. Also: New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1982.

- Selected Articles and Speeches. New York: International Publishers, 1984.

- The Essential Alexandra Kollontai. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008.

- The Workers Opposition in the Russian Communist Party: The Fight for Workers Democracy in the Soviet Union. St. Petersburg, FL: Red and Black Publishers, 2009.

- A comprehensive bibliography of Russian-language material by Kollontai appears in Clements, pp. 317–331.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Adding to the Dostoevskian melodrama, the first husband of Alexandra Kollontai's mother, an engineer named Mravinskii, was enlisted by the Tsar's secret police in 1881 to help ferret out a plot to kill the Tsar with dynamite placed under the street in a tunnel. Mravinskii helped police agents check for secret tunnels made by Narodnaia Volia terrorists – who managed to plant dynamite in this manner anyway. Tsar Alexander II was assassinated two weeks later by less sophisticated means when he changed his ordinary route through the streets, but Mravinskii was arrested when the dynamite tunnel was discovered, charged with misleading the police. Alexandra's mother persuaded her second husband to use his influence to aid her first, and as a result Mravinskii was saved from harsh Siberian exile, stripped of his rights and exiled to European Russia instead. Clements, p. 9.

- ↑ "The library loaned maps, globes, textbooks, and other materials to groups meeting in various parts of the city and sent out illegal populist and Marxist tracts under the cover of the legal activity." Clements, pp. 18.

- ↑ Louise Bryant (1885–1936) was a radical journalist and the wife of American journalist and Communist Party founder John Reed (1887–1920).

- ↑ Kollontai was awarded the Order of the Aztec Eagle on the basis of her friendship with Mexican Presidents Lázaro Cárdenas del Río (21 May 1895 – 19 October 1970), who served between 1934 and 1940, and Manuel Ávila Camacho (24 April 1897 – 13 October 1955), who served between 1940 and 1946.

Footnotes

- ↑ Clements, p. 3.

- 1 2 Clements, p. 4.

- ↑ Clements, p. 5.

- ↑ Kollontai, Aleksandra (1945). "Iz vozpominanii". Oktyabr (9): 61. Cited in Clements, p. 6.

- ↑ Clements, p. 11.

- 1 2 Clements, p. 12.

- ↑ Clements, p. 14.

- ↑ Kollontai, Aleksandra (1945). Den första etappen. Stockholm: Bonniers. pp. 218–219. Cited in Clements, p. 15.

- ↑ Clements, p. 15.

- ↑ Clements, p. 16.

- ↑ Clements, p. 18.

- ↑ Clements, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Clive James, Cultural Amnesia, p. 359.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Holt, p. 105.

- ↑ Holt, p. 80.

- ↑ Kollontai, Alexandra The Social Basis of the Woman Question 1909.

- ↑ Kollontai, Alexandra Women Workers Struggle For Their Rights 1919.

- ↑ de Haan et al., p. 255

- ↑ Hoskisson, Mark THE RED JACOBINS: Thermidor and the Russian Revolution in 1921. permanentrevolution.net

- ↑ Erofeev, V. (2011) Diplomat, Moskva.

- ↑ Mastny, Vojtech (1972). "Stalin and the Prospects of a Separate Peace in World War II". The American Historical Review. American Historical Association. 77: 1365–1388. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- 1 2 Ebert, 1999

- ↑ Lunacharsky, "О БЫТЕ:МОЛОДЕЖЬ И ТЕОРИЯ „СТАКАНА ВОДЫ"" ("On Everyday Life: Young People and the "Glass of Water" Theory)

- ↑ Bernstein, Frances Lee (2007). The Dictatorship of Sex: Lifestyle Advice for the Soviet Masses. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Kollontai, Alexandra (1999). Love of Worker Bees and A Great Love. Translated by Cathy Porter. Virago.

- ↑ Kollontai, A. (1920) "Communism and the Family," text Kommunistka.

- ↑ http://www.merlinpress.co.uk/acatalog/ALEXANDRA-KOLLONTAI.html

- ↑ Yerofeev, V. (2004) Diplomat, Moskow.

- ↑ http://spartacus-educational.com/RUSkollontai.htm

- 1 2 3 (in Russian) Alexandra Kollontai – the Soviet Ambassador.

- ↑ The Nobel Peace Prize: Revelations from the Soviet Past. Nobelprize.org. Retrieved on 16 June 2011.

- ↑ The Voice Of Russia. vor.ru (Spanish)

Bibliography

- Clements, Barbara Evans (1979). Bolshevik Feminist: The Life of Aleksandra Kollontai. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-31209-9.

- de Haan, Francisca; Daskalova, Krasimira; Loutfi, Anna (2006). A Biographical Dictionary of Women's Movements and Feminisms: Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe, 19th and 20th Centuries. ISBN 978-963-7326-39-4.

- Holt, Alix (trans.), ed. (1980) [1977]. Alexandra Kollontai Selected Writings. USA: Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-00974-3.

- Teresa Ebert, "Alexandra Kollontai and Red Love", 1999 (retrieved 2-24-2016)

Further reading

- Bobroff, Anne. "Alexandra Kollontai: Feminism, Workers' Democracy, and Internationalism," Radical America, vol. 13, no. 6 (Nov.-Dec. 1979), pp. 50–75.

- Farnsworth, Beatrice. Aleksandra Kollontai: Socialism, Feminism and the Bolshevik Revolution. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1980.

- Lilie, Stuart A. and John Riser. Four Socialist Reformers of Socialism: Alexandra Kollontai, Andrei Platonov, Robert Havemenn, and Stefan Heym. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2009.

- Porter, Cathy. Alexandra Kollontai: A Biography. New York: Doubleday, 1980.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexandra Kollontai. |

- Alexandra Kollontai Internet Archive at Marxists Internet Archive.

- Christine Thomas, "For socialism and women's liberation," (Archived 2009-10-25) Socialism Today, March 2003.

- Helen Ward, "Alexandra Kollontai," PermanentRevolution.net

- Gabrille Tousignant, "St-Petersbourg workers of the textile industry," Kollontai.net