Alcázar of Seville

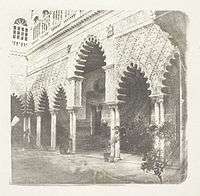

The Courtyard of the Maidens | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| Location |

Seville Province, Spain |

| Coordinates | 37°23′02″N 5°59′29″W / 37.3839°N 5.9914°W |

| Criteria |

Cultural: (i), (ii), (iii), (vi) |

| Reference | 383-002 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Website |

www |

Location of Alcázar of Seville | |

The Alcázar of Seville (Spanish "Reales Alcázares de Sevilla" or "Royal Alcazars of Seville", (Spanish pronunciation: [alˈkaθar])) is a royal palace in Seville, Andalusia, Spain, originally developed by Moorish Muslim kings.

The palace is renowned as one of the most beautiful in Spain, being regarded as one of the most outstanding examples of mudéjar architecture found on the Iberian Peninsula.[1] The upper levels of the Alcázar are still used by the royal family as the official Seville residence and are administered by the Patrimonio Nacional. It is the oldest royal palace still in use in Europe, and was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along with the Seville Cathedral and the General Archive of the Indies.[2]

The Reales Alcázares de Sevilla, a monumental complex that retains seven hectares of gardens and seventeen thousand square meters of buildings, was an authentic military and palatine acropolis that brought together several palaces and urban defenses still preserved that cover a wide chronological area between the 11th and 16th centuries with later modifications, having been the main palace of the Abbadí taifa kingdom, seat of one of the three capitals of the Almohad empire, palace of the Castilian monarchy during the Late Middle Ages and Royal House during the Early Modern Age.

Etymology

The term ‘Alcázar’ comes from the Hispano-Arabic word ‘Alqáşr’ meaning ‘Royal House’ or ‘Room of the Prince’ (whether fortified or not).[3]

History

- 1-Puerta del León

- 2-Sala de la Justicia y patio del Yeso (cyan)

- 3-Patio de la Montería (pink)

- 4-Cuarto del Almirante y Casa de Contratación (cream)

- 5-Palacio mudéjar o de Pedro I (red)

- 6-Palacio gótico (blue)

- 7-Estanque de Mercurio

- 8-Jardines (green)

- 9-Apeadero

- 10-Patio de Banderas

The Real Alcázar is situated near the Cathedral and the General Archive of the Indies in one of Spain's most emblematic areas.<ref name="Seville 2014, p.5"/

This plot was occupied from the 8th century BC[4] The remains of a building dating from the 1st century have been found, of which the function is not known with certainty.[4] This 1st-century building stretched from the Patio de Banderas to the interior of the current Alcázar. A Paleochristian church, identified by some as the Basilica of San Vicente, that was one of the three main temples of the city during the Visigothic time on its ruins was built. From this primitive temple some remains have been found in the Patio de Banderas.[4] Some capitals and stems of this temple were used for the Palace of Peter of Castile (Mudéjar Palace). The tomb of the Bishop Honorato, that probably was in this church, is currently in the cathedral.[4]

In 914 the Umayyads built an alcazaba with a quadrangular wall attached to the old Roman wall of the city. The only known access to this alcazaba was through a door that was located where currently the house number 16 of the Patio de Banderas.[4] This entrance consisted of an arch that preserves the north jamb.[4] Inside there were some simple outbuildings attached to the walls, such as warehouses, stables and barracks.[4]

After the loss of Cordobese control on Isbilya, an Abbadí aristocracy was created in the city. It completed a very constructive activity. In the middle of the 11th century, the alcazaba expanded to the south, doubling its surface. A new entrance was created with a control castle, of which a double horseshoe door is conserved in the street Joaquín Romero Murube.[4] In the interior a series of small buildings were placed and probably there was a main building, palatial, where is currently the Gothic Palace. In the second half of the 11th century, king Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad extended the fortress towards the west and some palace buildings were constructed. This was the original Alcázar of the Blessing (Al-Mubarak). Of the two alcazabas and the Alcázar of Al-Mutamid there are only a few vestiges in the walls.[4]

In the 12th century, the Almohades completely reformed all this space. They created a system of walls that united the Alcázar with other fortifications until the bed of the Guadalquivir. The Alcázar arrived until the tower of Abd el Aziz, located in the present avenue of the Constitution. In the interior, a dozen new and larger buildings were built.[4] The walls of the Alcázar were also part of a new and reformed fortifications for the defense of the city. These defensive works culminated at the beginning of 13th century with the construction of the Torre del Oro.[4]

The Almohades were the first to build a palace, that was called Al-Muwarak, on the site of the modern day Alcázar. It is one of the most representative monumental compounds in the city, the country and the Mediterranean culture. Its influences held within its walls and gardens began in the Arabic period and continued into the late Middle Ages Mudéjar period right through to the Renaissance, the Baroque era, and the 19th century.[5] Subsequent monarchs have made their own additions to the Alcázar.

The Castilian Court lived for decades in the old Almohad spaces.[4] Between 1252 and 1260 Alfonso X of Castile used the space of the main building to build the Gothic Palace.[6] In the 14th century king Peter of Castile overthrew three Almohad Palatine buildings to build the Mudéjar Palace, which was attached to the Gothic Alfonsí Palace.[4] Construction began in 1356 [7] and, according to the inscriptions of the own Alcázar, finalized in 1364.

Throughout history, the Alcázar has been the scene of various events related to the Spanish Crown. Between 1363 and 1365, it was visited by diplomats of the Court of Granada Ibn Khaldun, philosopher, and Ibn al-Khatib, chronicler and poet, to sign a peace treaty with King Peter of Castile.[8] In 1367 the Prince of Wales sent the English diplomats Neil Loring, Richard Punchardoun and Thomas Balastre to this Alcázar to meet Peter of Castile and collect some payments. In 1477 the Catholic Monarchs arrived at Seville, using the enclosure as a room, and a year later, on June 14, 1478, the second son, the prince John. It is known that this royal childbirth was attended by a Sevillian midwife known as "La Herradera" and had the presence, as witnesses designated by King Ferdinand, Garci Téllez, Alonso Melgarejo, Fernando de Abrejo and Juan de Pineda, as marked the Castilian norms, to dissipate the slightest doubt that the son was of the queen.[9] In 1526 the wedding of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor with his cousin Isabella of Portugal was celebrated in the Alcázar.[10]

The palace was the birthplace of Infanta Maria Antonietta of Spain (1729–1785), daughter of Philip V of Spain and Elisabeth Farnese. The king was in the city to oversee the signing of the Treaty of Seville (1729) which ended the Anglo-Spanish War (1727).

The Palace

The whole of the outer primitive enclosure, much of it outside the complex visited, preserves the almost intact perimeter walls.

The current tourist visit presents a route that does not take into account the historical perspective, being much more logical to understand the origin and evolution of the alcázar if it begins where it ends, from the north walls and the Patio de Banderas, first occupied zone, and go progressing from there to the interior.

Detail Gallery

The Gardens

All the palaces of Al Andalus had garden orchards with fruit trees, horticultural produce and a wide variety of fragrant flowers. The garden-orchards not only supplied food for the palace residents but had the aesthetic function of bringing pleasure. Water was ever present in the form of irrigation channels, runnels, jets, ponds and pools.

The gardens adjoining the Alcázar of Seville have undergone many changes. In the 16th century during the reign of Philip III the Italian designer Vermondo Resta introduced the Italian Mannerist style. Resta was responsible for the Galería de Grutesco (Grotto Gallery) transforming the old Muslim wall into a loggia from which to admire the view of the palace gardens.[11]

Mercury Pond

Taking the form of a large pond, located at the highpoint of the palace and thus higher than the rest of the gardens, the reservoir is presided over by the figure of the god Mercury, designed by Diego de Pesquera and cast by Bartolomé Morel in 1576. These men also contributed railings with shields with lions at their corners and 18 balls with pyramidal finials surrounding the pond. All these elements were originally gilded, but only traces remain of the coating. The backdrop is the "Gallery of the Grotesque," which was constructed on an old Almohad wall. Further contributions and a change decoration were made by Vermondo Resta around 1612, making this the most Mannerist section of the Alcázar. It consists of rustically worked stones of different types that simulate marine rocks. These stone elements form quadrangular spaces, and at the halfway point the walls are painted red to mimic red marble. The walls also show mythological figures and exotic birds, painted by Diego de Esquivel in the seventeenth century. The top of gallery is decorated with spires in the form of castle crenelation. In the front of the pond, there is a fountain with a recently restored water organ from the seventeenth century.[12]

In popular culture

- In 1962 the Alcázar was used as a set for Lawrence of Arabia.[13]

- The Patio de las Doncellas was used as the set for the court of the King of Jerusalem in the 2005 movie Kingdom of Heaven.

- Part of the fifth season of Game of Thrones was shot in several locations in the province of Seville, including the Alcázar.

- Part of the palace was used for filming for The White Princess and was used as the palace for Ferdinand II and Isabella I of Castile.

See also

References

- ↑ The Real Alcázar of Seville, Editorial Palacios y Museos, José Barea, 2014, p.47, ISBN 978-84-8003-637-5

- ↑ "Cathedral, Alcázar and Archivo de Indias in Seville". UNESCO. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ The Real Alcázar of Seville, Editorial Palacios y Museos, José Barea, 2014, p.5, ISBN 978-84-8003-637-5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Miguel Ángel Tabales Rodríguez (2001). "The Palatine transformation of the Alcázar of Seville, 914-1366" (PDF). Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa (12). pp. 195–213. ISSN 1130-9741

- ↑ "Royal Alcázar of Seville".

- ↑ Sebastián Fernández Aguilera (October–December 2015). The origin of the Palace of Peter of Castile in the Alcázar of Seville: the viewpoint now called of the Catholic Monarchs (PDF). Archivo Español de Arte. pp. 331–348. ISSN 0004-0428

- ↑ Olimpia López Cruz, Ana García Bueno and Víctor J. Medina Flórez (2011). The evolution of color in the eaves of the facade of the king D. Peter of Castile, Real Alcázar of Seville. Contributions of the study of materials to the identification of restoration interventions throughout its history. Arqueología de la Arquitectura. ISSN 1695-2731

- ↑ Ana Marín Fidalgo (2008). "Ibn Khaldun. Ambassador in the Sevillian court of King Peter of Castile". Ibn Khaldun. The Mediterranean in the fourteenth century. Rise and decline of empires. Fundación El Legado Andalusí. pp. 71–81. ISBN 978-849639521-3.

- ↑ Maria Dolores Robador (May 2003). Restoration of Prince's patio and garden. Notes of the Alcázar of Seville.

- ↑ Alfonso Pozo Rúiz. "How the King-Emperor came to marry in Seville". University of Seville.

- ↑ The Real Alcázar of Seville, Editorial Palacios y Museos, José Barea, 2014, p.121, ISBN 978-84-8003-637-5

- ↑ "Apuntes del Alcázar".

- ↑ Internet, Unidad Editorial. "El día que Lawrence de Arabia cambió el desierto por Sevilla". www.elmundo.es.

Bibliography

- ALMAGRO, A., “The Patio of the Croisser of the Reales Alcázares de Sevilla”, Al-Qantara, XX, 2, 1999, pp. 331-376.

- ALMAGRO, A., Planimetry of the Alcázar de Sevilla, CSIC, Granada, 2000.

- ALMAGRO, A., “The recovery of the medieval garden of the Courtyard of the Maidens”, Apuntes del Alcázar de Sevilla, 6, 2005, pp. 44-67.

- ALMAGRO, A., “The Alcázar of Seville. A Muslim palace for a Christian king”. XI Congress of Medieval Studies "Christians and Muslims in the Iberian peninsula: war, the border and coexistence, León, 23-26 de octubre de 2007, Fundación Sánchez-Albornoz, pp. 333-365.

- ALMAGRO, A., “The Reales Alcázares de Sevilla”, Artigrama, 22, 2007, pp. 155-185.

- ALMAGRO, A., “A new interpretation of the Patio of the Casa de Contratación of the Alcázar of Seville ", Al-Qanṭara, Vol. XXVIII, nº 1, 2007, pp. 181-228.

- ALMAGRO, A., “The palaces of Peter of Castile: architecture at the service of power”, Anales de Historia del Arte, vol. 23, II, 2013, p. 25-49.

- CÓMEZ, R., “The late medieval Alcázar ", Notes of the Real Alcázar de Sevilla, 14, 2013, pp. 94-137.

- LLEÓ, V., “El Alcázar”, Notes of the Real Alcázar de Sevilla, 14, 2013, pp. 20-29.

- MANZANO, R., “The patios and gardens of the Alcázar of Seville”, Notes of the Real Alcázar de Sevilla, 14, 2013, pp. 176-195.

- MARÍN FIDALGO, A. Mª, “The architecture of the Alcázar in the Age of Charles V”, Notes of the Real Alcázar de Sevilla, 14, 2013, pp. 138-153.

- ROBADOR, Mª D., “Restoration of the patios and gardens La Galera, Troya and Danza of the Real Alcazár of Seville”, Notes of the Alcázar de Sevilla, nº 8, 2007, pp. 54-93

- TABALES RODRÍGUEZ, M. Á., The Alcázar of Seville. Reflections on its origin and evolution in the Middle Ages. Archaeological memory 2000–2005, Sevilla, Consejería de Cultura Junta de Andalucía y Patronato del Real Alcázar de Sevilla, 2008.

- TABALES, M. Á., “Origin and Islamic Alcázar”, Notes of the Real Alcázar de Sevilla, 14, 2013, pp. 118-117.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alcázar of Seville. |

- InFocus: Alcázar of Seville (Sevilla, Spain) at HitchHikers Handbook

- Images of the Alcázar in Seville – 105 images with good descriptions of the Alcázar and its history.

- Casa de la Contratación – in depth historical article.

- El Real Alcázar de Sevilla (In Spanish, English and French)

- UNESCO World Heritage

- interiors and details pictures of Seville Alcazar

.jpg)