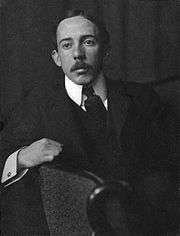

Alberto Santos-Dumont

| Alberto Santos-Dumont | |

|---|---|

|

c. 1902 | |

| Born |

20 July 1873 Palmira, Minas Gerais, Empire of Brazil |

| Died |

23 July 1932 (aged 59) Guarujá, São Paulo, Brazil |

| Resting place | São João Batista Cemetery, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Nationality | Brazilian |

| Occupation | Aviator, inventor |

| Honours | Grand Officier de la Légion d'honneur |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Alberto Santos-Dumont (Portuguese pronunciation: [awˈbɛʁtu ˈsɐ̃tuz duˈmõ]; 20 July 1873 – 23 July 1932, usually referred to as simply Santos-Dumont) was a Brazilian aviation pioneer, one of the very few people to have contributed significantly to the development of both lighter-than-air and heavier-than-air aircraft.

The heir of a wealthy family of coffee producers, Santos-Dumont dedicated himself to aeronautical study and experimentation in Paris, where he spent most of his adult life. In his early career he designed, built, and flew hot air balloons and early dirigibles, culminating in his winning the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize on 19 October 1901 for a flight that rounded the Eiffel Tower. He then turned to heavier-than-air machines, and on 23 October 1906 his 14-bis made the first powered heavier-than-air flight in Europe to be certified by the Aéro Club de France and the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. His conviction that aviation would usher in an era of worldwide peace and prosperity led him to freely publish his designs and forego patenting his various innovations.

Santos-Dumont is a national hero in Brazil, where it is popularly held that he preceded the Wright brothers in demonstrating a practical airplane. Countless roads, plazas, schools, monuments, and airports in Brazil are dedicated to him, and his name is inscribed on the Tancredo Neves Pantheon of the Fatherland and Freedom. He was a member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters from 1931 until his suicide in 1932.

Early life

Childhood

Santos-Dumont was born on 20 July 1873 in Cabangu in the Brazilian town of Palmira (today named Santos Dumont) in the state of Minas Gerais in southeast Brazil. He was youngest of the seven children born to Henrique Dumont, an engineer of French descent, and Francisca de Paula Santos. Santos-Dumont's father managed a coffee plantation on land owned by his wife's family, and later bought land in Ribeirão Preto on which he established a plantation of his own.[1] His extensive use of labor-saving inventions earned him a fortune, and he was known for a time as the "Coffee King of Brazil."

Santos-Dumont was fascinated by machinery, and while still a child he learned to drive the plantation's steam tractors and locomotives. He also read a great deal of the works of Jules Verne. He wrote in his autobiography that the dream of flying came to him while contemplating the magnificent skies of Brazil from the plantation.[2]

After basic instruction with private tutors, Santos-Dumont studied for a time at the Colégio Culto à Ciência in Campinas, after which he was sent to the Colégio Morton in São Paulo and the Escola de Minas in Minas Gerais.[3]

Move to France

In 1891 Santos-Dumont's father was partially paralyzed by a fall from a horse. He sold the plantation and went to Europe with his wife and Santos-Dumont in search of treatment.[4] In Paris, Santos-Dumont contacted a balloonist with the intention of making an ascent. The price quoted was 1,200 francs for a two-hour flight, plus payment for any damage caused and for returning the balloon to Paris. This was a considerable sum of money, and Santos-Dumont decided not to make the flight, reasoning that "If I risk 1,200 francs for an afternoon's pleasure I shall find it either good or bad. If it is bad the money will be lost. If it is good I shall want to repeat it and I shall not have the means."[5] After this he bought a Peugeot automobile, which he took with him when he returned to Brazil with his parents at the end of the year.

In 1892 the family returned to Europe, but Henriques felt too ill to continue on to Paris from Lisbon, and Alberto made the journey on his own. His father's health deteriorated and he decided to return to Brazil, where he died on 30 August 1892.[6]

For the next four years Alberto lived in Paris, studying physics, chemistry, mechanics, and electricity with the help of a private tutor, and returning to Brazil for short holidays. During this period he sold his Peugeot, replacing it with a more powerful and faster De Dion motor-tricycle.[7] In 1896 he returned to Brazil for a longer period, but began to miss Paris and so returned to Europe in 1897. Before embarking he had bought a copy of an account of Salomon Andrée's attempt to fly to the North Pole by balloon, written by the constructors of the balloon, MM. Lachambre and Machuron. In his biography Santos-Dumont describes the book as "a revelation", and resolved to make contact with the balloon constructors when he reached Paris.[8]

Aircraft

Balloons and dirigibles

On arrival in Paris Santos-Dumont contacted Lachambre and Machuron and arranged to make a flight, piloted by Alexis Machuron.[9] Taking off from Vaugirard, the flight lasted nearly two hours during which the balloon travelled 100 km (62 mi), coming down in the grounds of the Château de Ferrières. Enchanted by the experience, during the train journey back to Paris Santos-Dumont told Machuron that he wanted to have a balloon constructed for himself.[10] Before this was completed he gained experience by making a number of demonstration flights for Lachambre.[11]

Santos-Dumont's first balloon design, the Brésil, was remarkable for its small size and light weight, with a capacity of only 113 m3 (4,000 cu ft). In comparison, the balloon in which he had made his first flight had a capacity of 750 m3 (26,000 cu ft).

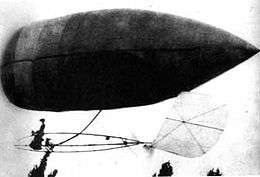

After numerous balloon flights, Santos-Dumont turned to the design of steerable balloons, or what became known as non-rigid airships, which could be propelled through the air rather than drifting along with the wind. A dirigible powered by an electric motor, La France, capable of flying at around 24 km/h (15 mph) had been successfully flown in 1884 by Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs, but their experiments had not progressed due to a lack of funding.[12] His first design was wrecked during its second flight on 29 September 1898, and he had even less luck with his second, which was abandoned after his first attempt to fly it on 11 May 1899.

A major cause of the accidents to his first two airships had been loss of pressure causing the elongated envelope to lose shape, and for his third design he adopted a much shorter and fatter envelope shape, and towards the end of 1899 made a number of successful flights in it. Meanwhile, he had an airship shed complete with its own hydrogen generating plant constructed at the Aéro-Club de France's flying grounds in the Parc Saint Cloud.[13]

The zenith of his lighter-than-air career came when Santos-Dumont won the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize for the first flight from the Parc Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back in less than 30 minutes, necessitating an average ground speed of at least 22 km/h (14 mph) to cover the 11 km (6.8 mi) in the allotted time.

To win the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize Santos-Dumont decided to build a bigger craft, the No. 5. On 8 August 1901, during one of his attempts, his dirigible began to lose hydrogen, and started to descend and was unable to clear the roof of the Trocadero Hotel. Santos-Dumont was left hanging in the basket from the side of the hotel. With the help of the Paris fire brigade, he climbed to the roof without injury, but the dirigible was a write-off. He immediately ordered a replacement to be constructed, the No.6[14]

On 19 October 1901, after several more attempts, Santos-Dumont succeeded in making the return flight. Immediately after he reached Saint-Cloud, a controversy broke out regarding the precise timing of the flight: although he had reached his destination in under 30 minutes there had been a delay of over a minute before his mooring line was picked up. However a satisfactory compromise was reached, and Santos-Dumont was eventually given the prize, which he announced would be given to the poor of Paris.[15] An additional 125,000 francs along with a gold medal was voted to him by the government of his native Brazil.

Winning the de la Meurthe prize made Santos-Dumont an international celebrity. He would float his No. 9 Baladeuse along Paris boulevards at rooftop level, sometimes landing at a cafe for lunch.[16] Parisians affectionately dubbed Santos-Dumont le petit Santos. The fashionable people of the day copied various aspects of his style of dress, from his high collared shirts to his signature Panama hat.

In 1904 Santos-Dumont shipped his new airship No. 7 from Paris to St. Louis to fly at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, to compete for the Grand Prize of $100,000 which was to be given to a flying machine (of any sort) that could make three round-trip flights over a 24 km (15 mile) L-shaped course at an average speed of 20 mph (32 km/h), later reduced to 15 mph (24 km/h). It was also necessary for the machine to land undamaged not more than 46 m (150 ft) from the starting point. Because he was the best-known aviator at the time, the Fair committee went to great lengths to ensure his participation, including modifying the rules. In conjunction with this trip he was invited to the White House to meet U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.[17]

However, upon arrival in St. Louis, Santos-Dumont found his airship’s envelope to be irreparably damaged. Sabotage, although suspected, was never proven. Santos-Dumont did not participate in the contest after suspicion of the deed, a repeat of a similar incident in London, began to focus on Santos-Dumont himself. He left the Fair and returned immediately to France.

In 1904, after Santos-Dumont complained to his friend Louis Cartier about the difficulty of checking his pocket watch during flight, Cartier created his first men's wristwatch, thus allowing Santos-Dumont to check his flight performance while keeping both hands on the controls.[18][19][20] Cartier still markets a line of Santos-Dumont watches and sunglasses.[21]

Heavier-than-air craft

Although Santos-Dumont continued to work on non-rigid airships, his primary interest soon turned to heavier-than-air aircraft. By 1905, he had finished his first fixed-wing aircraft design, and also a helicopter. Santos-Dumont finally succeeded in flying a heavier-than-air aircraft on 23 October 1906, piloting the 14-bis before a large crowd of witnesses at the grounds of Paris' Château de Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne for a distance of 60 metres (197 ft) at a height of about five meters (16 ft).[22] This was the first flight of a powered heavier-than-air machine in Europe to be certified by the Aéro-Club de France, and won the Deutsch-Archdeacon Prize for the first officially observed flight of more than 25 meters. (Although, by this time the Wright Brothers had already flown their Wright Flyer III for over half an hour[23][24] though not in a flight recognized by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale.) On 12 November 1906 Santos-Dumont set the first world record recognized by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale, by flying 220 metres (722 ft) in 21.5 seconds.[25][26]

.jpg)

Santos-Dumont's final design were the Demoiselle monoplanes (Nos. 19 to 22). These aircraft were used by Dumont for personal transport. The fuselage consisted of three specially reinforced bamboo booms, and the pilot sat a seat between the main wheels of a tricycle landing gear. The Demoiselle was controlled in flight by a tail unit that functioned both as elevator and rudder, and by wing warping (No. 20).

In 1908 Santos-Dumont started working with Adolphe Clément's Clement-Bayard company to mass-produce the Demoiselle No 19. They planned a production run of 100 units, built 50 but sold only 15, for 7,500 francs for each airframe. It was the world's first series production aircraft. By 1909 it was offered with a choice of three engines: Clement 20 hp; Wright 4-cyl 30 hp (Clement-Bayard had the license to manufacture Wright engines) and Clement-Bayard 40 hp designed by Pierre Clerget. The Demoiselle could achieve a speed of 120 km/h.[27]

The Demoiselle could be constructed in only 15 days. Possessing a good performance, flying at a speed of more than 100 km/h, the Demoiselle was the last aircraft designed by Santos-Dumont. The June 1910 edition of the Popular Mechanics magazine published drawings of the Demoiselle and stated, "This machine is better than any other which has ever been built, for those who wish to reach results with the least possible expense and with a minimum of experimenting." American companies sold drawings and parts for Demoiselles for several years afterward.

Later years

And in a meek tone exclaimed

congratulations

In the skies a new star shone

There appeared Santos Dumont.

Hail this star of South America

The land of the brave Indian warrior!

The greatest glory of the twentieth

century

–Eduardo das Neves

"The Conquest of Air" (1902)

Santos-Dumont's final flight as a pilot was made in a Demoiselle on 4 January 1910. The flight ended when a bracing wire snapped at an altitude of about 25 m (80 ft), causing a wing to collapse. Santo-Dumont suffered only bruises.[28][29]

In March 1910 Santos-Dumont announced that he was retiring from aviation. He secluded himself in his house and it was rumoured that he was suffering from a nervous breakdown caused by overwork, but it is probable that he was depressed about the multiple sclerosis from which he was later known to suffer.[30]

In 1911 he moved to the French seaside village of Bénerville (now Benerville-sur-Mer), where he took up astronomy as a hobby.[31] After the outbreak of war in 1914 his German-made telescope and unusual accent led to accusations he was a German spy tracking French naval activity, and his rooms searched by French police. Upset by the allegation and depressed about his illness Santos-Dumont burned all his papers and plans.[32] For this reason there is little direct information available about his designs today. He spent much of the 1920s in Swiss and French sanatoria, though returning to Brazil at times.

For his arrival in Brazil in 1928, a dozen members of the Brazilian scientific community boarded a seaplane with the intention of paying a flying welcome to the returning aviator on the luxury liner Cap Arcona. The seaplane, however, crashed with the loss of all on board.[33] The loss deepened Santos-Dumont's growing despondency, and he returned to Switzerland.

Death

In 1931 Santos-Dumont's nephew went to Switzerland and brought him to Brazil. Seriously ill and said to be depressed over his multiple sclerosis and the use of aircraft in warfare during São Paulo's Constitutionalist Revolution, he hanged himself on 23 July 1932 in the city of Guarujá[33] (although his death certificate gives the cause of death as "cardiac collapse").[34]

After lying in state for two days in the crypt of São Paulo Cathedral, his body was taken to Rio de Janeiro, where after a state funeral he was buried in the São João Batista Cemetery.[35][36] His heart is preserved in a golden globe at Brazil's National Air and Space Museum.

Private life

Santos-Dumont, a lifelong bachelor, did seem to have a particular affection for a married Cuban-American woman named Aida de Acosta, who in 1903 became the only other person that he ever permitted to fly one of his airships – his No. 9 (and thereby most likely becoming the first woman to pilot a powered aircraft). Until the end of his life, he kept a picture of her on his desk alongside a vase of fresh flowers. Nonetheless, there is no indication that Santos-Dumont and Acosta stayed in touch after her flight; upon his death she was reported as saying that she hardly knew him.

Santos-Dumont is also known to not only have often used an equal sign (=) between his two surnames in place of a hyphen, but also seems to have preferred that practice, to display equal respect for his French and Brazilian-Portuguese ethnicities.[37]

A Encantada

In Brazil, Santos-Dumont bought a small lot on the side of a hill in the city of Petrópolis, in the mountains near Rio de Janeiro, and in 1918 built a small house there filled with imaginative mechanical gadgetry including an alcohol-fueled heated shower of his own design. The hill was purposefully chosen because of its great steepness as a proof that ingenuity could make it possible to build a comfortable house in that unlikely site. After building it, he used to spend his summers there to escape the heat in Rio, calling it A Encantada ("The Enchanted") after its street, Rua do Encanto. The treads of the exterior stairs are hollowed alternately on the right and left, to enable people to climb them comfortably. The house is now a museum.

Honors and legacy

- 1905 – Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur

- 1909 – Officier de la Légion d'Honneur[38]

- 1913 – Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur

- 1929 – Grand Officier de la Légion d'Honneur[39]

- Santos-Dumont is a small lunar impact crater that lies in the northern end of the Montes Apenninus range at the eastern edge of the Mare Imbrium

- The aviator gives his name to the city of Santos Dumont, in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The Cabangu farm, where he was born is in this municipality . The Faculdades Santos Dumont is a group of private higher learning colleges in the city.[40]

- The city of Dumont, in the state of São Paulo, near Ribeirão Preto is so named because it is located where what used to be one of the largest coffee farms in the world, owned by Alberto Santos-Dumont's father. It was sold in 1896 to a British company, the Dumont Coffee Company.

- Airports in Rio de Janeiro (see Santos Dumont Airport) and Paranaguá (see Paranaguá Airport) are named after him.

- The Rodovia Santos Dumont is a highway in the state of São Paulo.

- The Brazilian Air Force (Command of Aeronautics) awards the Santos Dumont Medal of Merit to important personalities in the world of aviation. The state government of Minas Gerais has a similar medal.

- The Réseau Santos Dumont is a cooperative university network between France and Brazil, instituted by the French and Brazilian Ministries of Education in 1994, with 26 universities in each country.

- The single Blériot 5190 flying boat, intended to carry out a transatlantic mail service to Brazil, was named Santos-Dumont

- The American Office of Naval Research in San Diego, California named one of its research airships the 600B Santos Dumont.[41]

- The Historic and Cultural Institute of Aeronautics of Brazil has instituted the Santos Dumont Annual Prize of Journalism for the best reports in the media about aeronautics.

- The Lycée Polyvalent Santos Dumont is a lyceum in Saint-Cloud, France[42]

- Santos-Dumont is mentioned as a pioneer of aviation, specifically in the area of dirigibles, in Robert A. Heinlein's Job: A Comedy of Justice (1984).

- The official Brazilian presidential aircraft, an Airbus Corporate Jet tail number FAB2101, was named Alberto Santos Dumont.

- H.G. Wells' "The Truth About Pyecraft" (1903) refers to Santos-Dumont's skill as an aviator.

- The American aviation magazine Flying ranked Santos-Dumont eighth on its list of the "51 Heroes of Aviation" in 2013.[43]

- The opening ceremony of the 2016 Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro included a recreation of Santos-Dumont's 1906 flight.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, pp.17–18

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, p.21

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, p.23

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, p.24

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, pp.27–28

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, p.33

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, p.39

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, p.31

- ↑ "M. Santos Dumont". l'Aérophile (in French): 72. April 1901.

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904,pp. 33-42

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904,p. 48

- ↑ Hallion 2003 pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, p. 129

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, p. 174

- ↑ "M. Santos Dumont's Balloon". The Times (36591). London. 21 October 1901. col A, p. 4.

- ↑ Hamre, Bonnie. "Alberto Santos Dumont." About.com. Retrieved: 20 August 2012.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=80YaAAAAIAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=santos+dumont

- ↑ "The History of Cartier". InterWatches. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ "Aviation Pioneer Scored A First in Watch-Wearing." The New York Times, 25 October 1975. Retrieved: 21 July 2009.

- ↑ 100 Designs/100 Years: A Celebration of the 20th Century (aka 100 Designs/100 Years: Innovative Designs of the 20th Century) (with Arlette Barré-Despond), Hove, UK: RotoVision, 1999 | ISBN 2-88046-442-0

- ↑ Cartier sunglasses. "Cartier rimmed sunglasses" (English). cartier.com. Retrieved: 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Gibbs-Smith, Charles H. "Hops and Flights: A roll call of early powered take-offs." Flight, Volume 75, Issue 2619, 3 April 1959, p. 469. Retrieved: 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Sharpe, Michael (2000). Biplanes, Triplanes and Seaplanes. Friedman/Fairfax. p. 311. ISBN 1-58663-300-7.

- ↑ "Were the Wright brothers really first? Not in Brazil". cnet.com.

- ↑ Jines, Ernest. "Santos Dumont in France 1906–1916: The Very Earliest Early Birds." earlyaviators.com, 25 December 2006. Retrieved: 17 August 2009.

- ↑ "Cronologia de Santos Dumont" (in Portuguese). santos-dumont.net.Retrieved: 12 October 2010.

- ↑ Hartmann, Gérard. "Clément-Bayard, sans peur et sans reproche" (French). hydroretro.net. Retrieved: 14 November 2010.

- ↑ Santos-Dumont's Accident Flight, 8 January 1910, p.28.

- ↑ "NOVA 124: Wings of Madness." PBS. Retrieved: 14 November 2010.

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, pp236-8

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, p.242

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, pp245-6

- 1 2 Hallion 2003, p. 93.

- ↑ Wykeham 1962, p.260 (fn)

- ↑ "The Late M. Santos Dumont". News. The Times (46320). London. 19 December 1932. col F, p. 11.

- ↑ "Alberto Santos Dumont Lies In State in Brazil's Capital." The New York Times, 19 December 1932.

- ↑ Gray 2006, p.4.

- ↑ "Les Croix de Aéro-Locomotion". l'Aérophile: 356. 1 August 1909.

- ↑ "Convocations". L'Aérophile (in French). 1–15 December 1929.

- ↑ "FESJ – Fundação Educacional São José." www.fsd.edu.br. Retrieved: 9 August 2010.

- ↑ "Airship Santos Dumont to Conduct Test Phase." Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. www.news.navy.mil. Retrieved: 9 August 2010.

- ↑ "Saint-Cloud." ac-versailles.fr.

- ↑ "51 Heroes of Aviation". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

Bibliography

- Byars, Mel. 100 Designs/100 Years: A Celebration of the 20th Century (aka 100 Designs/100 Years: Innovative Designs of the 20th Century) (with Arlette Barré-Despond), Hove, UK: RotoVision, 1999 | ISBN 2-88046-442-0

- de Barros, Henrique Lins. Santos Dumont and the Invention of the Airplane (PDF). Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Ministry of Science & Technology and the Brazilian Centre for Research in Physics, 2006. ISBN 978-85-85752-17-0.

- de Mattos, Bento S. "Santos Dumont and the Dawn of Aviation," AIAA paper # 2004-106, 42nd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, Nevada, January 2004.

- de Mattos, Bento S. "Short History of Brazilian Aeronautics," AIAA paper # 2006-328, 44th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, Nevada, January 2006.

- de Mattos, Bento S. "Open Source Philosophy and the Dawn of Aviation," J. Aerospace Technology Management, São José dos Campos, Vol. 4, No. 3, July–September 2012, pp. 355–379.

- Garrett, Charles Hall. "A Builder of Successful Air-Ships". The World's Work: A History of Our Time, VIII, May 1904: pp. 4737–4739.

- Gray, Carroll F. "The 1906 Santos-Dumont No. 14bis". World War I Aeroplanes, Issue #194, November 2006, pp. 4–21.

- Hallion, Richard P. Taking Flight. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-516035-5.

- Hansen, James R. First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 978-0-7432-5631-5.

- Hoffman, Paul. Wings of Madness: Alberto Santos Dumont and the Invention of Flight. New York: Hyperion Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7868-6659-5.

- Santos Dumont, Alberto. My Airships. London, G. Richards, 1904 hos / Follow Your Dreams: The Story of Alberto Santos Dumont, (bilingual, Portuguese/English). Rio de Janeiro: Prometheus Press, 2005. ISBN 978-85-99240-02-1.

- Winters, Nancy. Man Flies: The Story of Alberto Santos-Dumont, Master of the Balloon. New York: Ecco Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-88001-636-0.

- Wykeham, Peter. Santos Dumont: A Study in Obsession. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962. ISBN 978-0-405-12210-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alberto Santos-Dumont. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Alberto Santos-Dumont. |

- Santos-Dumont, My Airships (tr. of Dans l'air)

- Works by or about Alberto Santos-Dumont at Internet Archive

- PBS Nova: Wings of Madness

- U. S. Centennial of Flight Commission Dumont

- Alberto Santos Dumont Article by writer Patricia Nell Warren.

- History of Aviation: Brazil, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

- Aviation Pioneer Santos-Dumont, Technological Institute of Aeronautics (ITA).

- Open Source Philosophy and the Dawn of Aviation Article published by Bento S. de Mattos.

- Alberto Santos-Dumont at Find a Grave

| Preceded by Graça Aranha (founder) |

Brazilian Academy of Letters – Occupant of the 38th chair 1931 — 1932 |

Succeeded by Celso Vieira |