Ajaccio

| Ajaccio | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefecture and commune | |||

|

The center of Ajaccio | |||

| |||

Ajaccio | |||

|

Location within Corsica region  Ajaccio | |||

| Coordinates: 41°55′36″N 8°44′13″E / 41.9267°N 8.7369°ECoordinates: 41°55′36″N 8°44′13″E / 41.9267°N 8.7369°E | |||

| Country | France | ||

| Region | Corsica | ||

| Department | Corse-du-Sud | ||

| Arrondissement | Ajaccio | ||

| Canton | Ajaccio-1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 | ||

| Intercommunality | Pays Ajaccien | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor (2015–2020) | Laurent Marcangeli | ||

| Area1 | 82.03 km2 (31.67 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2014)2 | 68,587 | ||

| • Density | 840/km2 (2,200/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| INSEE/Postal code | 2A004 /20000 | ||

| Elevation |

0–787 m (0–2,582 ft) (avg. 38 m or 125 ft) | ||

| Website | http://www.ajaccio.fr/ | ||

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | |||

Ajaccio (Latin: Adiacium; French: Ajaccio French pronunciation: [aʒaksjo]; Corsican: Aiacciu [aˈjattʃu]; Italian: Ajaccio, [aˈjattʃo]) is a French commune, prefecture of the department of Corse-du-Sud, and head office of the Collectivité territoriale de Corse (capital city of Corsica). It is also the largest settlement on the island. Ajaccio is located on the west coast of the island of Corsica, 210 nautical miles (390 km) southeast of Marseille.

The original city went into decline in the Middle Ages, but began to prosper again after the Genoese built a citadel in 1492 to the south of the earlier settlement. After the Corsican Republic was declared in 1755 the Genoese continued to hold several citadels, including Ajaccio, until the French took control of the island.

The inhabitants of the commune are known as Ajacciens or Ajacciennes.[1] The most famous of these is Napoleon Bonaparte who was born in Ajaccio in 1769, and whose ancestral home, the Maison Bonaparte, is now a museum. Other dedications to him in the city include Ajaccio Napoleon Bonaparte Airport.[2]

Geography

Location

Ajaccio is located on the west coast of the island of Corsica, 210 nautical miles (390 km) southeast of Marseille. The commune occupies a sheltered position at the foot of wooded hills on the northern shore of the Gulf of Ajaccio between Gravona and the pointe de la Parata and includes the îles Sanguinaires (Bloody Islands). The harbour lies to the east of the original citadel below a hill overlooking a peninsula which protects the harbour in the south where the Quai de la Citadelle and the Jettée de la Citadelle are. The modern city not only encloses the entire harbour but takes up the better part of the Gulf of Ajaccio and in suburban form extends for some miles up the valley of the Gravona River. The flow from that river is nearly entirely consumed as the city's water supply. Many beaches and coves border its territory and the terrain is particularly rugged in the west where the highest point is 790 m (2,592 ft).

- Ajaccio Marina

The Bay

The Bay The lighthouse of the citadel of Ajaccio overlooking the bay

The lighthouse of the citadel of Ajaccio overlooking the bay Îles Sanguinaires

Îles Sanguinaires- The market

| Neighbouring communes and towns[3] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Villanova | Alata | Afa |  |

| Mediterranean Sea | |

Bastelicaccia | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Mediterranean Sea | Mediterranean Sea | |||

Urbanism

.jpg)

Although the commune of Ajaccio has a large area (82.03 km2), only a small portion of this is urbanized. Therefore, the urban area of Ajaccio is located in the east of the commune on a narrow coastal strip forming a densely populated arc. The rest of the territory is natural with habitation of little importance and spread thinly. Suburbanization occurs north and east of the main urban area.

The original urban core, close to the old marshy plain of Cannes was abandoned in favour of the current city which was built near the Punta della Lechia. It has undergone various improvements, particularly under Napoleon, who originated the two current major structural arteries (the Cours Napoleon oriented north-south and the Cours Grandval oriented east-west).

Ajaccio experienced a demographic boom in the 1960s, which explains why 85% of dwellings are post-1949.[4] This is reflected in the layout of the city which is marked by very large areas of low-rise buildings and concrete towers, especially on the heights (Jardins de l'Empereur) and in the north of the city - e.g. the waterfront, Les Cannes, and Les Salines. A dichotomy appears in the landscape between the old city and the imposing modern buildings. Ajaccio gives the image of a city built on two different levels.

Climate

The city has a Mediterranean climate which is Csa in the Köppen climate classification. The average annual sunshine is 2726 hours.

There are important local climatic variations, especially with wind exposure and total precipitation, between the city centre, the airport, and the îles Sanguinaires. The annual average rainfall is 645.6 mm (25.4 in) at the Campo dell'Oro weather station (as per the chart) and 523.9 mm (20.6 in) at the Parata: the third-driest place in metropolitan France.[5] The heat and dryness of summer are somewhat tempered by the proximity of the Mediterranean Sea except when the sirocco is blowing. In autumn and spring, heavy rain-storm episodes may occur. Winters are mild and snow is rare. Ajaccio is the French city which holds the record for the number of thunderstorms in the reference period 1971-2000 with an average of 39 thunderstorm days per year.[6]

On 14 September 2009, the city was hit by a tornado with an intensity of F1 on the Fujita scale. There was little damage except torn billboards, flying tiles, overturned cars, and broken windows but no casualties.

| Town | Sunshine (hours/yr) |

Rain (mm/yr) | Snow (days/yr) | Storm (days/yr) | Fog (days/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Average | 1,973 | 770 | 14 | 22 | 40 |

| Ajaccio | 2,735 | 616 | 2 | 39 | 3[8] |

| Paris | 1,661 | 637 | 12 | 18 | 10 |

| Nice | 2,724 | 767 | 1 | 29 | 1 |

| Strasbourg | 1,693 | 665 | 29 | 29 | 56 |

| Brest | 1,605 | 1,211 | 7 | 12 | 75 |

Weather Data for Ajaccio

| Climate data for Ajaccio, Altitude 4m, from 1981 to 2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.4 (72.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

29.6 (85.3) |

32.2 (90) |

34.6 (94.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

40.3 (104.5) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.0 (104) |

35.0 (95) |

29.4 (84.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

40.3 (104.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

13.9 (57) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.6 (63.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

3.0 (37.4) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.7 (2.232) |

45.1 (1.776) |

49.1 (1.933) |

54.8 (2.157) |

44.0 (1.732) |

22.1 (0.87) |

6.7 (0.264) |

19.7 (0.776) |

51.5 (2.028) |

85.6 (3.37) |

103.9 (4.091) |

76.4 (3.008) |

615.6 (24.236) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 68.4 |

| Average snowy days | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 78 | 76 | 76 | 78 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 79.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 137.2 | 154.9 | 211.7 | 224.9 | 286.8 | 324.7 | 369.8 | 335.1 | 257.6 | 200.6 | 136.5 | 116.2 | 2,755.8 |

| Source #1: Meteo France[9][10] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity and snowy days, 1961–1990)[11] | |||||||||||||

Heraldry

|

In 1575, the Senate of Genoa granted to the city of Ajaccio Arms of blue with a silver column sumounted by the Arms of Genoa between two white greyhounds. This is not the current Arms.

Blazon: |

Toponymy

Several hypotheses have been advanced as to the etymology of the name Ajaccio (Aiacciu in Corsican, Addiazzo on old documents). Among these, the most prestigious suggests that the city was founded by the Greek legendary hero Ajax and named after him. Other more realistic explanations are, for example, that the name could be related to the Tuscan agghiacciu meaning "sheep pens". Another explanation, supported by Byzantine sources from around the year 600AD called the city Agiation which suggests a possible Greek origin for the word,[12] agathè could mean "good luck" or "good mooring" (this was also the root of the name of the city of Agde).

History

Antiquity

The city was not mentioned by the Greek geographer Ptolemy of Alexandria in the 2nd century AD despite the presence of a place called Ourkinion in the Cinarca area. It is likely that the city of Ajaccio had its first development at this time. The 2nd century was a period of prosperity in the Mediterranean basin (the Pax Romana) and there was a need for a proper port at the head of the several valleys that lead to the Gulf able to accommodate large ships. Some important underwater archaeological discoveries recently made of Roman ships tend to confirm this.

Further excavations conducted recently led to the discovery of important early Christian remains likely to significantly a reevaluation upwards of the size of Ajaccio city in Late Antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages. The city was in any case already significant enough to be the seat of a diocese, mentioned by Pope Gregory the Great in 591. The city was then further north than the location chosen later by the Genoese - in the location of the existing quarters of Castel Vecchio and Sainte-Lucie.

The earliest certain written record of a settlement at Ajaccio with a name ancestral to its name was the exhortation in Epistle 77 written in 601AD by Gregory the great to the Defensor Boniface, one of two known rectors of the early Corsican church,[13] to tell him not to leave Aléria and Adjacium without bishops.[14] There is no earlier use of the term and Adjacium is not an attested Latin word, which probably means that it is a Latinization of a word in some other language. The Ravenna Cosmography of about 700 AD cites Agiation,[15] which sometimes is taken as evidence of a prior Greek city, as -ion appears to be a Greek ending. There is, however, no evidence at all of a Greek presence on the west coast and the Ionians at Aléria on the east coast had been expelled by the Etruscans long before Roman domination.

Ptolemy, who must come the closest to representing indigenous names, lists the Lochra River just south of a feature he calls the "sandy shore" on the southwest coast. If the shore is the Campo dell'Oro (Place of Gold) the Lochra would seem to be the combined mouth of the Gravona and Prunelli Rivers, neither one of which sounds like Lochra.

North of there was a Roman city, Ourchinion. The western coastline was so distorted, however, that it is impossible to say where Adjacium was; certainly, he would have known its name and location if he had had any first-hand knowledge of the island and if in fact it was there. Ptolemy's Ourchinion is further north than Ajaccio and does not have the same name. It could be Sagone.[16] The lack of correspondence between Ptolemaic and historical names known to be ancient has no defense except in the case of the two Roman colonies, Aleria and Mariana. In any case the population of the region must belong to Ptolemy's Tarabeni or Titiani people, neither of which are ever heard about again.

Archaeological evidence

The population of the city throughout the centuries maintained an oral tradition that it had originally been Roman. Travellers of the 19th century could point to the Hill of San Giovanni on the northwest shore of the Gulf of Ajaccio, which still had a cathedral said to have been the 6th-century seat of the Bishop of Ajaccio. The Castello Vecchio ("old castle"), a ruined citadel, was believed to be Roman but turned out to have Gothic features. The hill was planted with vines. The farmers kept turning up artifacts and terracotta funerary urns that seemed to be Roman.

In the 20th century the hill was covered over with buildings and became a part of downtown Ajaccio. In 2005 construction plans for a lot on the hill offered the opportunity to the Institut national de recherches archéologiques preventatives (Inrap) to excavate. They found the baptistry of a 6th-century cathedral and large amounts of pottery dated to the 6th and 7th centuries AD; in other words, an early Christian town. A cemetery had been placed over the old church. In it was a single Roman grave covered over with roof tiles bearing short indecipherable inscriptions. The finds of the previous century had included Roman coins. This is the only evidence so far of a Roman city continuous with the early Christian one.[17]

The medieval Genoese period

It has been established that after the 8th century the city, like most other Corsican coastal communities, strongly declined and disappeared almost completely. Nevertheless, a castle and a cathedral were still in place in 1492 which last was not demolished until 1748.

Towards the end of the 15th century, the Genoese were eager to assert their dominance in the south of the island and decided to rebuild the city of Ajaccio. Several sites were considered: the Pointe de la Parata (not chosen because it was too exposed to the wind), the ancient city (finally considered unsafe because of the proximity of the salt ponds), and finally the Punta della Lechia which was finally selected.

Work began on the town on 21 April 1492 south of the Christian village by the Bank of Saint George at Genoa, who sent Cristoforo of Gandini, an architect, to build it. He began with a castle on Capo di Bolo, around which he constructed residences for several hundred people.[18]

The new city was essentially a colony of Genoa. The Corsicans were restricted from the city for some years.

Nevertheless, the town grew rapidly and became the administrative capital of the province of Au Delà Des Monts (more or less the current Corse-du-Sud). Bastia remained the capital of the entire island.

Although at first populated exclusively by the Genoese, the city slowly opened to the Corsicans while the Ajaccians, almost to the French conquest, were legally citizens of the Republic of Genoa and were happy to distinguish themselves from the insular paesani who lived mainly in Borgu, a suburb outside the city walls (the current rue Fesch was the main street).

The attachment to France

Ajaccio was occupied from 1553 to 1559 by the French but it again fell to the Genoese after the Treaty of Cateau Cambresis in the latter year.[19]

Subsequently, the Republic of Genoa was strong enough to keep Corsica until 1755, the year Pasquale Paoli proclaimed the Corsican Republic. Paoli took most of the island for the republic but he was unable to force Genoese troops out of the citadels of Saint-Florent, Calvi, Ajaccio, Bastia and Algajola. Leaving them there, he went on to build the nation, while the Republic of Genoa was left to ponder prospects and solutions. Their ultimate solution was to sell Corsica to France in 1768 and French troops of the Ancien Régime replaced Genoese ones in the citadels, including Ajaccio's.

Corsica was formally annexed to France in 1780.

Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte (born as Nabulione Buonaparte) was born at Ajaccio in the same year as the Battle of Ponte Novu, 1769. The Bonapartes at the time had a modest four-story home in town (now a museum known as Maison Bonaparte) and a rarely used country home in the hills north of the city (now site of the Arboretum des Milelli). The father of the family, attorney Charles-Marie Buonaparte, was secretary to Pasquale Paoli during the Corsican Republic.

After the defeat of Paoli, the Comte de Marbeuf began to meet with some leading Corsicans to outline the shape of the future and enlist their assistance. The Comte was among a delegation from Ajaccio in 1769, offered his loyalty and was appointed assessor.

Marbeuf also offered Charles-Marie Buonaparte an appointment for one of his sons to the Military College of Brienne, but the child had to be under 10. There is a dispute concerning Napoleon's age because of this requirement; the emperor is known to have altered the civic records at Ajaccio concerning himself and it is possible that he was born in Corte in 1768 when his father was there on business. In any case Napoleon went to Brienne from 1779–1784.[20]

At Brienne Napoleon concentrated on studies. He wrote a boyish history of Corsica. He did not share his father's views but held Pasquale Paoli in high esteem and was at heart a Corsican nationalist. The top students were encouraged to go into the artillery. After graduation and a brief sojourn at the Military School of Paris Napoleon applied for a second-lieutenancy in the artillery regiment of La Fère at Valence and after a time was given the position. Meanwhile, his father died and his mother was cast into poverty in Corsica, still having four children to support. Her only income was Napoleon's meagre salary.

The regiment was in Auxonne when the revolution broke out in the summer of 1789. Napoleon returned on leave to Ajaccio in October, became a Jacobin and began to work for the revolution. The National Assembly in Paris united Corsica to France and pardoned its exiles. Paoli returned in 1790 after 21 years and kissed the soil on which he stood. He and Napoleon met and toured the battlefield of Paoli's defeat. A national assembly at Orezza created the department of Corsica and Paoli was subsequently elected president. He commanded the national guard raised by Napoleon. After a brief return to his regiment Napoleon was promoted to First Lieutenant and came home again on leave in 1791. The death of a rich uncle relieved the family's poverty.

All officers were recalled from leave in 1792, intervention threatened and war with Austria (Marie-Antoinette's homeland) began. Napoleon returned to Paris for review, was exonerated, then promoted to Captain and given leave to escort his sister, a schoolgirl, back to Corsica at state expense. His family was prospering; his estate increased.

Napoleon became a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Corsican National Guard. Paoli sent him off on an expedition to Sardinia, ordered by France, under Paolis's nephew but the nephew had secret orders from Paoli to make sure the expedition failed.[21] Paoli was now a conservative, opposing the execution of the king and supporting an alliance with Great Britain. Returning from Sardinia Napoleon with his family and all his supporters were instrumental in getting Paoli denounced at the National Convention in Paris in 1793. Napoleon earned the hatred of the Paolists by pretending to support Paoli and then turning against him (payment, one supposes, for Sardinia).

Paoli was convicted in absentia, a warrant was issued for his arrest (which could not be served) and Napoleon was dispatched to Corsica as Inspector General of Artillery to take the citadel of Ajaccio from the royalists who had held it since 1789. The Paolists combining with the royalists defeated the French in two pitched battles and Napoleon and his family went on the run, hiding by day, while the Paolists burned their estate. Napoleon and his mother, Laetitia, were taken out by ship in June 1793, by friends while two of the girls found refuge with other friends. They landed in Toulon with only Napoleon's pay for their support.

The Bonapartes moved to Marseille but in August Toulon offered itself to the British and received the protection of a fleet under Admiral Hood. The Siege of Toulon began in September under revolutionary officers mainly untrained in the art of war. Napoleon happened to present socially one evening and during a casual conversation over a misplaced 24-pounder explained the value of artillery. Taken seriously he was allowed to bring up over 100 guns from coastal emplacements but his plan for the taking of Toulon was set aside as one incompetent officer superseded another. By December they decided to try his plan and made him a Colonel. Placing the guns at close range he used them to keep the British fleet away while he battered down the walls of Toulon. As soon as the Committee of Public Safety heard of the victory Napoleon became a Brigadier General, the start of his meteoric rise to power.

The Bonapartes were back in Ajaccio in 1797 under the protection of General Napoleon. Soon after Napoleon became First Consul and then emperor, using his office to spread revolution throughout Europe. In 1811 he made Ajaccio the capital of the new Department of Corsica. Despite his subsequent defeat by the Prussians, Russians, and British, his exile and his death, no victorious power reversed that decision or tried to remove Corsica from France. Among the natives, though Corsican nationalism is strong, and feeling often runs high in favour of a union with Italy; loyalty to France, however, as evidenced by elections, remains stronger.

19th and 20th centuries

In the 19th century Ajaccio became a popular winter resort of the high society of the time, especially for the English, in the same way as Monaco, Cannes, and Nice. An Anglican Church was even built.

The first prison in France for children was built in Ajaccio in 1855: the Horticultural colony of Saint Anthony. It was a correctional colony for juvenile delinquents (from 8 to 20 years old), established under Article 10 of the Act of 5 August 1850. Nearly 1,200 children from all over France stayed there until 1866, when it was closed. Sixty percent of them perished, the victims of poor sanitation and malaria which infested the unhealthy areas that they were responsible to clean.[22]

Contemporary history

On 9 September 1943, the people of Ajaccio rose up against the Nazi occupiers[23] and became the first French town to be liberated from the domination of the Germans. General Charles de Gaulle went to Ajaccio on 8 October 1943 and said: "We owe it to the field of battle the lesson of the page of history that was written in French Corsica. Corsica to her fortune and honour is the first morsel of France to be liberated; which was done intentionally and willingly, in the light of its liberation, this demonstrates that these are the intentions and the will of the whole nation."

Throughout this period, no Jew was executed or deported from Corsica through the protection afforded by its people and its government. This event now allows Corsica to aspire to the title "righteous among the nations", as no region except for the commune Le Chambon-sur-Lignon in Haute-Loire carries this title. Their case is being investigated as of 2010.[24]

Since the middle of the 20th century, Ajaccio has seen significant development. The city has seen population growth and considerable urban sprawl. Today Ajaccio is the capital of Corsica and the main town of the island and seeks to establish itself as a true regional centre.[25]

Economy

The city is, with Bastia, the economic, commercial and administrative centre of Corsica. Its urban area of nearly 90,000 inhabitants is spread over a large part of the Corse-du-Sud, on either side of the Gulf of Ajaccio and up the valley of the Gravona. Its business is primarily oriented towards the services sector.

The services sector is by far the main source of employment in the city. Ajaccio is an administrative centre comprising communal, intercommunal, departmental, regional, and prefectural services.

It is also a shopping centre with the commercial streets of the city centre and the areas of peripheral activities such as that of Mezzavia (hypermarket Géant Casino) and along the ring road (hypermarket Carrefour and E. Leclerc).

Tourism is one of the most vital aspects of the economy, split between the seaside tourism of summer, cultural tourism, and fishing. A number of hotels, varying from one star to five star, are present across the commune.

Ajaccio is the seat of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Ajaccio and Corsica South. It manages the ports of Ajaccio, Bonifacio, Porto-Vecchio, Propriano and the Tino Rossi marina. It also manages Ajaccio airport[26] and Figari airport as well as the convention centre and the Centre of Ricanto.

Secondary industry is underdeveloped, apart from the aeronautical company Corsica Aerospace Composites CCA, the largest company on the island with 135 employees at two sites.[27] The storage sites of GDF Suez (formerly Gaz de France) and Antargaz in the district of Vazzio are classified as high risk.

Energy

The Centrale EDF du Vazzio, a heavy oil power station, provides the south of the island with electricity. The Gravona Canal delivers water for consumption by the city.

Transport

Road access

By road, the city is accessible from National Route NR194 from Bastia and NR193 via NR196 from Bonifacio.

These two main axes, as well as the roads leading to suburban villages, connect Ajaccio from the north - the site of Ajaccio forming a dead end blocked by the sea to the south. Only the Cours Napoleon and the Boulevard du Roi Jerome cross the city.

Along with the high urban density, this explains the major traffic and parking problems especially during peak hours and during the summer tourist season. A bypass through several neighbourhoods is nearing completion.

Communal bus services

The Transports en commun d'Ajaccio (TCA) provide services on 21 urban routes, one "city" route for local links and 20 suburban lines. The frequency varies according to demand with intervals of 30 minutes for the most important routes:[28]

A park and ride with 300 spaces was built at Mezzana in the neighbouring commune of Sarrola-Carcopino in order to promote intermodality between cars and public transport.[29] It was inaugurated on 12 July 2010.[30]

In addition, the municipality has introduced a Tramway between Mezzana station in the suburbs and Ajaccio station located in the centre.

Airport

The city is served by an Ajaccio Napoleon Bonaparte Airport which is the headquarters of Air Corsica, a Corsican airline. It connects Ajaccio to a number of cities in mainland France (including Paris, Marseille, Nice, and Brive) and to places in Europe to serve the tourist industry.

The airline CCM Airlines also has its head office on the grounds of the Airport.[31]

Port

The port of Ajaccio is connected to the French mainland on an almost daily basis (Marseille, Toulon, Nice). There are also occasional links to the Italian mainland (Livorno) and to Sardinia, as well as a seasonal service serving Calvi and Propriano.[32] The two major shipping companies providing these links are SNCM and Corsica Ferries.

Ajaccio has also become a stopover for cruises with a total of 418,086 passengers in 2007—by far the largest in Corsica and the second-largest in France (after Marseille, but ahead of Nice/Villefranche-sur-Mer and Cannes). The goal is for Ajaccio to eventually become the premier French port for cruises as well as being a main departure point.[32]

The Port function of the city is also served by the commercial, pleasure craft, and artisanal fisheries (3 ports).[32]

Railways

The railway station in Ajaccio belongs to Chemins de Fer de la Corse and is located near the port at the Square Pierre Griffi. It connects Ajaccio to Corte, Bastia (3h 25min) and Calvi.

There are two optional stops:

- Salines Halt north of the city in the district of the same name

- Campo dell'Oro Halt near the airport

Administration

Ajaccio was successively:

- Capital of the district of the department of Corsica in 1790 to 1793

- Capital of the department of Liamone from 1793 to 1811

- Capital of the department of Corsica from 1811 to 1975

- Capital of the region and the collectivité territoriale de Corse since 1970 and the department of Corse-du-Sud since 1976

Policy

Ajaccio remained (with some interruptions) an electoral stronghold of the Bonapartist (CCB) party until the municipal elections of 2001. The outgoing municipality was then beaten by a left-wing coalition led by Simon Renucci which gathered Social Democrats, Communists, and Charles Napoleon - the pretender to the imperial throne.

List of Successive Mayors of Ajaccio[33]

| Mayors from the French Revolution to 1935 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

| 1790 | 1790 | Jean Jèrome Levie | ||

| 1791 | 1796 | Vincenté Guitera | ||

| 1796 | 1796 | Lodovico Ornano | ||

| 1798 | 1798 | François Marie Levie | ||

| 1798 | 1798 | Thomas Tavera | ||

| 1798 | 1798 | Antoine Tagliafico | ||

| 1799 | 1800 | J. B. Pozzo di Borgo | ||

| 1800 | 1801 | Jean Jèrome Levie | ||

| 1801 | 1805 | Pierre Stephanopoli | ||

| 1805 | 1815 | François Levie | ||

| 1815 | 1815 | Jean Noël Martinenghi | ||

| 1815 | 1816 | François Levie | ||

| 1816 | 1817 | Georges Stephanopoli | ||

| 1817 | 1819 | Adorno de Baciocchi | ||

| 1819 | 1822 | J. B. Colonna de Bozzi | ||

| 1822 | 1826 | J. B. Spotorno | ||

| 1826 | 1832 | Constantin Stephanopoli | ||

| 1832 | 1837 | Cunéo d'Ornano | ||

| 1837 | 1848 | Paul François Peraldi | ||

| 1848 | 1848 | Bernardin Poli | ||

| 1848 | 1855 | Laurent Zevaco | ||

| 1855 | 1860 | Antoine Decosmi | ||

| 1860 | 1867 | François Xavier Braccini | ||

| 1867 | 1870 | Louis Nyer | ||

| 1870 | 1870 | Joseph Fil | ||

| 1870 | 1871 | Nicolas Peraldi | ||

| 1871 | 1871 | Joseph Fil | ||

| 1871 | 1873 | Nicolas Peraldi | ||

| 1873 | 1876 | F. X. Forcioli Conti | ||

| 1876 | 1877 | Nicolas Peraldi | ||

| 1877 | 1877 | Joseph Fil | ||

| 1877 | 1884 | Nicolas Peraldi | Republicain | |

| 1884 | 1893 | Joseph Pugliesi | CCB[34] | |

| 1893 | 1896 | Pierre Petreto | CCB | |

| 1896 | 1900 | Joseph Pugliesi | CCB | |

| 1900 | 1904 | Pierre Bodoy | CCB | |

| 1904 | 1919 | Dominique Pugliesi Conti | CCB | |

| 1919 | 1925 | Jérôme Peri | Radical | |

| 1925 | 1931 | Dominique Paoli | CCB | |

| 1931 | 1931 | Joseph Marie François Spoturno | ||

| 1931 | 1934 | François Coty | CCB | |

| 1934 | 1935 | Hyacinthe Campiglia | CCB | |

| Mayors from 1935 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

| 1935 | 1943 | Dominique Paoli | CCB | |

| 1943 | 1945 | Eugène Macchini | CCB | |

| 1945 | 1947 | Arthur Giovoni | PCF | |

| 1947 | 1949 | Nicéphore Stephanopoli de Commene | CCB | |

| 1949 | 1953 | Antoine Serafini | CCB | |

| 1953 | 1959 | François Maglioli | CCB | |

| 1959 | 1964 | Antoine Serafini | CCB | |

| 1964 | 1975 | Pascal Rossini | CCB | |

| 1975 | 1994 | Charles Napoléon Ornano | CCB | |

| 1994 | 2001 | Marc Marcangeli | CCB | Doctor |

| 2001 | 2014 | Simon Renucci | CSD[35] | Doctor |

| 2014 | 2014 | Laurent Marcangeli | ||

| 2014 | 2015 | vacant | ||

| 2015 | Laurent Marcangeli | |||

(Not all data is known)

Quarters

10 Quarters are recognized by the municipality.[36]

- Cannes-Binda: a popular area north of the city, consisting of Housing estates, classed as a Sensitive urban zone (ZUS) with Les Salines, subject to a policy of urban renewal

- Centre Ville: The tourist heart of the city consisting of shopping streets and major thoroughfares

- Casone: a bourgeois neighbourhood with an affluent population located in the former winter resort on the heights of the southern city.

- Jardins del'Empereur: a city classified as a Sensitive urban zone (ZUS) on the heights of the city, consisting of Housing estates overlooking the city

- Mezzavia: northern quarter of the town with several subdivisions and areas of business and economic activities

- Octroi-Sainte Lucie: constitutes the northern part of the city centre near the port and the railway station

- Pietralba: popular quarter northeast of the city, classified ZUS

- Résidence des Îles: quarter to the south of the city near the tourist route of Sanguinaires in a quality environment

- Saint-Jean: collection of buildings for a population with low incomes, close to the historic urban core of the city, classified as a Sensitive urban zone (ZUS)

- Saline: popular quarter north of the city, consisting of large apartment blocks, classed as a Sensitive urban zone (ZUS) with Les Cannes, subject to a policy of urban renewal

- Vazzio: quarter northeast of the city, near the airport, the EDF Central, and the Francois Coty stadium.

Intercommunality

Since December 2001, Ajaccio has been part of the Communauté d'agglomération du Pays Ajaccien with nine other communes: Afa, Alata, Appietto, Cuttoli-Corticchiato, Peri, Sarrola-Carcopino, Tavaco, Valle-di-Mezzana, and Villanova.

Origins

The geopolitical arrangements of the commune are slightly different from those typical of Corsica and France. Usually an arrondissement includes cantons and a canton includes one to several communes including the chef-lieu, "chief place", from which the canton takes its name. The city of Ajaccio is one commune, but it contains four cantons, Cantons 1–4, and a fraction of Canton 5. The latter contains three other communes: Bastelicaccia, Alata and Villanova, making a total of four communes for the five cantons of Ajaccio.[37]

Each canton contains a certain number of quartiers, "quarters". Cantons 1, 2, 3, 4 are located along the Gulf of Ajaccio from west to east, while 5 is a little further up the valleys of the Gravona and the Prunelli Rivers. These political divisions subdivide the population of Ajaccio into units that can be more democratically served but they do not give a true picture of the size of Ajaccio. In general language, "greater Ajaccio" includes about 100,000 people with all the medical, educational, utility and transportational facilities of a big city. Up until World War II it was still possible to regard the city as being a settlement of narrow streets localized to a part of the harbour or the Gulf of Ajaccio: such bucolic descriptions do not fit the city of today, and travellogues intended for mountain or coastal recreational areas do not generally apply to Corsica's few big cities.

The arrondissement contains other cantons that extend generally up the two rivers into central Corsica.

Twinning

Ajaccio has twinning associations with:[38]

Jena, Germany, since 2003

Jena, Germany, since 2003  Larnaca, Cyprus, since 1989

Larnaca, Cyprus, since 1989  Palma de Mallorca, Spain, since 1980

Palma de Mallorca, Spain, since 1980 Dana Point, California, United States, since 1990

Dana Point, California, United States, since 1990 La Maddalena, Italy, since 1991

La Maddalena, Italy, since 1991  Marrakech, Morocco, since 2005

Marrakech, Morocco, since 2005

Demography

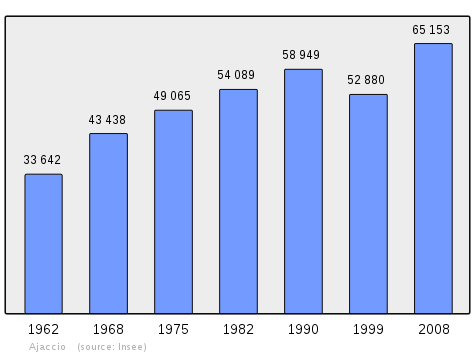

The demographic development of Ajaccio occurred mainly between 1945 and 1975 with a doubling of the population of the city in that period. This is explicable in the 1950s by the rural exodus. From the 1960s, the city saw the coming of "Pied-Noirs" (French Algerians) including immigrants from the Maghreb and French from mainland France.

In 2010, the commune had 65,542 inhabitants. The evolution of the number of inhabitants is known through the population censuses conducted in the town since 1793. From the 21st century, a census of municipalities with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants is held every five years, unlike larger towns that have a sample survey every year.[Note 1]

| 1793 | 1800 | 1806 | 1821 | 1831 | 1836 | 1841 | 1846 | 1851 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 6,570 | 7,203 | 7,401 | 8,920 | 9,003 | 9,834 | 11,541 | 11,944 |

| 1856 | 1861 | 1866 | 1872 | 1876 | 1881 | 1886 | 1891 | 1896 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11,049 | 14,089 | 14,558 | 16,545 | 17,050 | 18,005 | 17,576 | 20,197 | 20,561 |

| 1901 | 1906 | 1911 | 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | 1946 | 1954 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21,779 | 22,264 | 19,227 | 22,614 | 23,392 | 23,917 | 37,146 | 31,434 | 32,997 |

| 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33,642 | 43,438 | 49,065 | 54,089 | 58,315 | 52,880 | 63,723 | 64,432 | 65,153 |

| 2009 | 2010 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64,306 | 65,542 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Sources : Ldh/EHESS/Cassini until 1962, INSEE database from 1968 (population without double counting and municipal population from 2006)

Health

Ajaccio has three hospital sites:

- the Misericordia Hospital, built in 1950, is located on the heights of the city centre. This is the main medical facility in the region.

- The Annex Eugenie.

- the Psychiatric Hospital of Castelluccio is 5 kilometres (3 miles) west of the city centre and is also home of cancer services and long-stay patients.[39]

Education

Ajaccio is the headquarters of the Academy of Corsica.

The city of Ajaccio has:[40]

- 18 nursery schools (16 public and 2 private)

- 17 primary schools (15 public and 2 private)

- 6 colleges

- 5 Public Schools:

- Collège Arthur-Giovoni

- Collège des Padule

- Collège Laetitia Bonaparte

- Collège Fesch

- EREA

- 1 Private School: Institution Saint Paul

- 5 Public Schools:

- 3 sixth-form colleges/senior high schools

- 2 public schools:

- Lycée Laetitia Bonaparte

- Lycée Fesch

- 1 private: Institution Saint Paul

- 2 public schools:

- 2 LEP (vocational high schools)

- Lycée Finosello

- Lycée Jules Antonini

Higher education is undeveloped except for a few BTS and IFSI, the University of Corsica Pascal Paoli is located in Corte. A research facility of INRA is also located on Ajaccio.[41]

Culture and heritage

Ajaccio has a varied tourism potential, with both a cultural framework in the centre of the city and a natural heritage around the coves and beaches of the Mediterranean Sea, as well as the Natura 2000 reserve of the îles Sanguinaires.

Civil heritage

The commune has many buildings and structures that are registered as historical monuments:

- The Monument to General Abbatucci in the Place Abbatucci (1854)

[42]

[42] - The Monument to Napoleon I in the Place d'Austerlitz (20th century)

[43]

[43] - The Baciocchi Family Mansion at 9 Rue Bonaparte (18th century)

[44]

[44] - The Fesch Palace at 48 bis Rue Cardinal-Fesch (1827)

[45]

[45] - The Monument to the First Consul in the Place Foch (1850)

[46]

[46] - The Peraldi House at 18 Rue Forcioli-Conti (1820)

[47]

[47] - The Grand Hotel at Cours Grandval (1869)

[48]

[48] - The old Château Conti at Cours Grandval (19th century)

[49]

[49] - The Monument to Napoleon and his brothers in the Place du General de Gaulle (1864)

[50]

[50] - The Monument to Cardinal Fesch at the Cour du Musée Fesch (1856)

[51]

[51] - The old Alban Factory at 89 Cours Napoleon (1913)

[52]

[52] - The Milelli House in the Saint-Antoine Quarter (17th century)

[53]

[53] - The Hotel Palace-Cyrnos (1880),

[54] an old Luxury Hotel from the 19th century and a famous palace of the old days in the quarter "for foreigners" now converted into housing.

[54] an old Luxury Hotel from the 19th century and a famous palace of the old days in the quarter "for foreigners" now converted into housing. - The Lantivy Palace (1837),

[55] an Italian palace now headquarters of the prefecture of Corsica.

[55] an Italian palace now headquarters of the prefecture of Corsica. - The Hotel de Ville (1836)

[56]

[56] - Napoleon Bonaparte's House (17th century)

[57] now a national museum: the Maison Bonaparte

[57] now a national museum: the Maison Bonaparte - The old Lazaretto of Aspretto (1843)

[58]

[58] - The Citadel (1554)

[59]

[59] - The Sawmill at Les Salines (1944)

[60]

[60] - The Lighthouse on the Sanguinaires Islands (1844)

[61]

[61]

- Other sites of interest

- The Monument in the Place du Casone

- The old town and the Borgu are typically Mediterranean with their narrow streets and picturesque buildings

- The Place Bonaparte, a quarter frequented chiefly by winter visitors attracted by the mild climate of the town.[19]

- The Musée Fesch houses a large collection of Italian Renaissance paintings

- The Bandera Museum, a History Museum of Mediterranean Corsica

- The Municipal library has many early printed books of the 15th and 16th centuries

- The area known as "for foreigners" has a number of old palaces, villas, and buildings once built for the wintering British in the Belle Époque such as the Anglican Church and the Grand Hotel Continental. Some of the buildings are unfortunately in bad condition and very degraded, others were destroyed for the construction of modern buildings. The area still retains a beautiful architecture and is very pleasant to visit.

- The Genoese towers: Torra di Capu di Fenu, Torra di a Parata, and Torra di Castelluchju in the Îles Sanguinaires archipelago

- The Square Pierre Griffi (in front of the railway station), hero of the Corsican Resistance, one of the members of the Pearl Harbour secret mission,[62] the first operation launched in occupied Corsica to coordinate resistance.

- The Statue of Commandant Jean L'Herminier (in front of the ferry terminal), commander of the French submarine Casabianca (Q183) which actively participated in the struggle for the liberation of Corsica in September 1943.

Religious heritage

The town is the seat of a bishopric dating at least from the 7th century. It has tribunals of first instance and of commerce, training colleges, a communal college, a museum and a library; the three latter are established in the Palais Fesch, founded by Cardinal Fesch, who was born at Ajaccio in 1763.[19]

The commune has several religious buildings and structures that are registered as historical monuments:

- The former Episcopal Palace at 24 Rue Bonaparte (1622)

[63]

[63] - The Oratory of Saint Roch at Rue Cardinal-Fesch (1599)

[64]

[64] - The Chapel of Saint Erasme or Sant'Erasmu at 22 Rue Forcioli-Conti (17th century)

[65]

[65] - The Oratory of Saint John the Baptist at Rue du Roi-de-Dome (1565)

[66]

[66] - The Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta at Rue Saint-Charles (1582)

[67] from the Renaissance which depended on the diocese of Ajaccio and where Napoleon was baptized with its organ from Cavaillé-Coll.[68]

[67] from the Renaissance which depended on the diocese of Ajaccio and where Napoleon was baptized with its organ from Cavaillé-Coll.[68] - The Chapel of the Greeks on the Route des Sanguiunaires (1619)

[69]

[69] - The Early Christian Baptistery of Saint John (6th century)

[70]

[70] - The Imperial Chapel (1857)

[71] houses the graves of Napoleon's parents and his brothers and sisters.

[71] houses the graves of Napoleon's parents and his brothers and sisters.

- Other religious sites of interest

- The Church of Saint Roch, Neoclassical architecture by Ajaccien project architect Barthélémy Maglioli (1885)

Environmental heritage

- Sanguinaires Archipelago:

- The Route des Sanguinaires runs along the southern coast of the city after the Saint François Beach. It is lined with villas and coves and beaches. Along the road is the Ajaccio cemetery with the grave of Corsican singer Tino Rossi.

- At the mouth of the Route des Sanguinaires is the Pointe de la Parata near the archipelago and the lighthouse.

The Saint François Beach

The Saint François Beach Gulf of Ajaccio

Gulf of Ajaccio The iles sanguinaires and views of la Parata from the sentier des crêtes

The iles sanguinaires and views of la Parata from the sentier des crêtes Along the sentier des crêtes: Skull Rock

Along the sentier des crêtes: Skull Rock

- The Sentier des Crêtes (Crest Trail) starts from the city centre and is an easy hike offering splendid views of the Gulf of Ajaccio. The shores of the Gulf are dotted with a multitude of small coves and beaches ideal for swimming and scuba diving.

- Many small paths traversing the maquis (high ground covered in thick vegetation) in the commune from which the Maquis resistance network was named.

Interests

- The city has two marinas and a casino.

- The main activities are concentrated in the city centre on the Route des Sanguinaires (cinemas, bars, clubs etc.).

Films made in Ajaccio

- Napoléon, one of the last successful French silent films by Abel Gance in 1927.

- Les Radonneurs, a French film directed by Philippe Harel in 1997.

- Les Sanguinaires, a film by Laurent Cantet in 1998.

- The Amazing Race, an American TV series by Elise Doganieri and Bert Van Munster in 2001 (season 6 episode 9).

- L'Enquête Corse, directed by Alain Berberian in 2004.

- Trois petites filles, a French film directed by Jean-Loup Hubert in 2004.

- Joueuse (Queen To Play), a French film directed by Caroline Bottaro in 2009.

Sports

There are various sports facilities developed throughout the city.

- AC Ajaccio is a French Ligue 2 football club who play at the Stade François Coty (13,500 seats) in the north-east of the city

- Gazélec Football Club Ajaccio, in Ligue 1, are an amateur club who play at the Stade Ange Casanova located at Mezzavia, 2,900 seats.

- GFCO Ajaccio handball

- GFCO Ajaccio Volleyball

- GFCO Ajaccio Basketball

- Vignetta Racecourse

Notable people linked to the commune

- Carlo Buonaparte (1746–1785), politician, father of Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Joseph Fesch (1763–1839), cardinal.

- Felix Baciocchi (1762–1841), general of the armies of the Revolution and the Empire, brother in law of the Emperor Napoleon 1st, Grand Duke of Tuscany.

- Napoleon Bonaparte was born on 15 August 1769 and died on 5 May 1821 on the island of Saint Helena United Kingdom, Emperor of France.

- Lucien Bonaparte (1775–1840), Prince of Canino and Musignano, Interior Minister of France.

- Elisa Bonaparte (1777–1820), Grand Duchess of Tuscany.

- Louis Bonaparte (1778–1846), King of Holland.

- Caroline Bonaparte (1782–1839), Queen Consort of Naples and Sicily.

- Jérôme Bonaparte (1784–1860), King of Westphalia.

- Irène Bordoni (1895–1953), singer, Broadway theatre & film actress.

- Michel Giacometti (1929–1990), Ethnomusicologist who worked primarily in Portugal.

- François Duprat (1941–1978), French writer.

- Michel Ferracci-Porri (born 1949), French writer.

- Jean-Michel Cavalli (born 1959), coach of the Algeria national football team

- François Coty (1874-1934, industrialist and politician, he revolutionized the perfume business

- Tino Rossi (1907–1983), French singer and actor

- Alizée (1984-), French singer

Military

Units that were stationed in Ajaccio:

- 163rd Infantry Regiment, 1906

- 173rd Infantry Regiment

- The Aspretto naval airbase for seaplanes 1938-1993

Gallery

Early city map

Early city map Statue of Napoleon in Roman garb

Statue of Napoleon in Roman garb Napoleon's birth house

Napoleon's birth house

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ At the beginning of the 21st century, the methods of identification have been modified by law No. 2002-276 of 27 February 2002 Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., the so-called "law of local democracy" and in particular Title V "census operations" which allow, after a transitional period running from 2004 to 2008, the annual publication of the legal population of the different French administrative districts. For municipalities with a population greater than 10,000 inhabitants, a sample survey is conducted annually, the entire territory of these municipalities is taken into account at the end of the period of five years. The first "legal population" after 1999 under this new law came into force on 1 January 2009 and was based on the census of 2006.

References

- ↑ Inhabitants of Corse-du-Sud (in French)

- ↑ "What’s in an eponym? Celebrity airports - could there be a commercial benefit in naming?". Centre for Aviation.

- ↑ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ The Cities of France, by Fabriès-Verfaillie et Stragiotti, 2000 (in French)

- ↑ France, Meteo. "PREVISIONS METEO FRANCE - Site Officiel de Météo-France - Prévisions gratuites à 15 jours sur la France et à 10 jours sur le monde". www.meteofrance.com. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ MétéoFrance.

- ↑ Paris, Nice, Strasbourg, Brest

- ↑ "Normales climatiques 1981-2010 : Ajaccio". www.lameteo.org. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ "Données climatiques de la station de Ajaccio" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Climat Corse". Meteo France. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Normes et records 1961-1990: Ajaccio - Campo dell'Oro (2A) – altitude 4m" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ↑ Manuscript variants are Agration and Agiagium but the use of a Greek ending does not necessarily indicate anything at all about ethnicity. At this late date geographers used either Greek or Latin forms at will. The word is no more decipherable in Greek than it is in Latin; attempts to connect two or three letters with Indo-European roots amount to speculation.

- ↑ Richards, Jeffrey (1979). The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages, 476–752. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 318. ISBN 0-7100-0098-7.

- ↑ See below under Bibliography.

- ↑ Anonymous of Ravenna; Guido; Gustav Parthey; Moritz Pinder (1860). Ravennatis Anonymi Cosmographia et Guidonis Geographica. Berolini: in aedibvs Friderici Nicolai. p. 413. (in Latin). Downloadable Google Books.

- ↑ Massimi, Pierre; Jose Tomazi (2002). "A corsica in la carta geografica di Ptolomey" (PDF). InterRomania. Centru Culturale, Universita di Corsica. Archived from the original (pdf) on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2008. (in Corsican).

- ↑ "Discovery of an Early Christian Baptistery in Ajaccio". Inrap. 9 June 2005. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ↑ "History of the city of Ajaccio". Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- 1 2 3

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ajaccio". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 451.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ajaccio". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 451. - ↑ Baring-Gould, Sabine (2006). The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Adamant Media Corporation. Chapter 1. ISBN 0-543-95815-9.

- ↑ Cinti, Maurizio (20 April 1995). "La Maddalena, 22/25 February 1793". Military Subjects: Battles & Campaigns. The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ↑ "Créer un site web gratuit - pages perso Orange". site.voila.fr. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ Préfecture of Corsica: The Liberation of Corsica Archived 24 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. (in French)

- ↑ Le Figaro:Corsicans want to be the island of the "Just among the nations" (in French)

- ↑ "French Cities" by Fabriès-Verfaillie et Stragiotti, 2000. (in French)

- ↑ CCI of Ajaccio: Airport Archived 26 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. (in French)

- ↑ Corses Composites Aéronautiques (in French)

- ↑ Transport en commun d’Ajaccio (TCA) (in French)

- ↑ Communauté d’Agglomération of Pays Ajaccien (in French)

- ↑ www.ca-ajaccien.fr and Archived 18 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (in French)

- ↑ "Relations Clientèle." CCM Airlines. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Ajaccio and South Corsica (in French)

- ↑ Weinland, Robert. "francegenweb.org - votre service benevole d'assistance genealogique". www.francegenweb.org. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ Comité central bonapartiste

- ↑ Corse social-democrate

- ↑ Official website of the city of Ajaccio (in French)

- ↑ "Décret n° 2014-229 du 24 février 2014 portant délimitation des cantons dans le département de la Corse-du-Sud". Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ National Commission for Decentralised cooperation (in French)

- ↑ Castelluccio - Public Establishment of Health (in French)

- ↑ Academy of Corsica (in French)

- ↑ French Cities" by Fabriès-Verfaillie et Stragiotti, 2000 (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA2A001904 Monument to General Abbatucci (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA2A001900 Monument to Napoleon I (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099141 Baciocchi Family Mansion (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099071 Fesch Palace (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA2A001905 Monument to the First Consul (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099067 Peraldi House (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099134 Grand Hotel (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099063 Château Conti (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA2A001903 Monument to Napoleon and his brothers (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA2A001902 Monument to Cardinal Fesch (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099142 Alban Factory (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099065 Milelli House (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099135 Hotel Palace-Cyrnos (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099128 Lantivy Palace (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099127 Hotel de Ville (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099066 Napoleon Bonaparte's House (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099064 Lazaretto of Aspretto (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099062 Citadel]] (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA2A001311 Sawmill]] (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA2A001274 Lighthouse]] (in French)

- ↑ See "Mission secrète Pearl Harbour" in the French Wikipedia (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099070 Episcopal Palace (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099069 Oratory of Saint Roch (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099061 Chapel of Saint Erasme or Sant'Erasmu (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099068 Oratory of Saint John the Baptist (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099058 Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta (in French)

- ↑ Ajaccio Cathedral, Organ of the Cathedral of Cavaillé-Coll (1849) - Cicchero (1997) (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099059 Chapel of the Greeks (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA2A000004 Baptistery of Saint John (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00099060 Imperial Chapel (in French)

Bibliography

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Ajaccio". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Ajaccio". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

![]() Works related to Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series II/Volume XIII/Gregory the Great/Book XI/Letter 37 at Wikisource

Works related to Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series II/Volume XIII/Gregory the Great/Book XI/Letter 37 at Wikisource

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ajaccio. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ajaccio. |

- City of Ajaccio website (in French)

- The Communauté d'Agglomération du Pays Ajaccien (CAPA) website (in French)

- Tourism Office of Ajaccio website (in French)