Aikido techniques

Aikido techniques are frequently referred to as waza 技 (which is Japanese for technique, art or skill). Aikido training is based primarily on two partners practicing pre-arranged forms (kata) rather than freestyle practice. The basic pattern is for the receiver of the technique (uke) to initiate an attack against the person who applies the technique—the 取り tori, or shite 仕手, (depending on aikido style) also referred to as (投げ nage (when applying a throwing technique), who neutralises this attack with an aikido technique.[1]

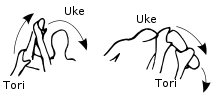

Both halves of the technique, that of uke and that of tori, are considered essential to aikido training.[1] Both are studying aikido principles of blending and adaptation. Tori learns to blend with and control attacking energy, while uke learns to become calm and flexible in the disadvantageous, off-balance positions in which tori places him. This "receiving" of the technique is called ukemi.[1] Uke continuously seeks to regain balance and cover vulnerabilities (e.g., an exposed side), while tori uses position and timing to keep uke off-balance and vulnerable. In more advanced training, uke may apply reversal techniques (返し技 kaeshi-waza) to regain balance and pin or throw tori.

Ukemi (受身) refers to the act of receiving a technique. Good ukemi involves attention to the technique, the partner and the immediate environment - it is an active rather than a passive "receiving" of Aikido. The fall itself is part of Aikido, and is a way for the practitioner to receive, safely, what would otherwise be a devastating strike or throw (or joint lock control) and return to a standing position in one fluid movement. The person throwing (or applying other technique) must take into account the ukemi ability of his partner, as well as the physical space: walls, weapons (wooden tantō, bokken, jō) on the tatami, and the aikido practitioners nearby.

Uke must attack with a strength and speed appropriate to the skill level of the tori; in the case of beginners, this means an attack of far less severity than would be encountered in a real-life self-defense situation.

Training techniques

- Boat-rowing exercise (船漕運動 Funakogi undō) / Rowing the boat (取り船 torifune) [2] teaches movement from the hip rather than relying on muscle strength of the arms

- First teaching exercise (一教運動 Ikkyo undō) trains students to enter with both arms forward in the tegatana (手刀) position.

- Body change (体の変更 Tai no henko) altering the direction of an incoming attack

- Seated breathing method (座技呼吸法 Suwariwaza kokyūhō) / Breathing action (呼吸動作 Kokyūdōsa) / Breathing belly method (呼吸丹田方 Kokyūtandenhō) breathing is important in the execution of all aikido techniques. Here "breathing" has an additional meaning of "match with" or "accord," as the efforts of tori must agree with the direction and strength with which his wrists are held by uke.

Initial attacks

Aikido techniques are usually a defense against an attack; therefore, to practice aikido with their partner, students must learn to deliver various types of attacks. Although attacks are not studied as thoroughly as in striking-based arts such as karate or taekwondo, "honest" or "sincere" attacks (a strong strike or an immobilizing grab) are needed to study correct and effective application of technique.

Many of the strikes (打ち uchi) of aikido are often said to resemble cuts from a sword or other grasped object, which indicates its origins in techniques intended for armed combat. Other techniques, which appear to explicitly be punches (tsuki), are also practiced as thrusts with a knife or sword. Kicks are generally reserved for upper-level variations; reasons cited include that falls from kicks are especially dangerous, and that kicks (high kicks in particular) were uncommon during the types of combat prevalent in feudal Japan. Some basic strikes include:

- Front-of-the-head strike (正面打ち shōmen'uchi) a vertical knifehand strike to the head. In training, this is usually directed at the forehead or the crown for safety, but more dangerous versions of this attack target the bridge of the nose and the maxillary sinus.

- Side-of-the-head strike (横面打ち yokomen'uchi) a diagonal knifehand strike to the side of the head or neck.

- Chest thrust (胸突き mune-tsuki) a punch to the torso. Specific targets include the chest, abdomen, and solar plexus. Same as "middle-level thrust" (中段突き chūdan-tsuki), and "direct thrust" (直突き choku-tsuki).

- Face thrust (顔面突き ganmen-tsuki) a punch to the face. Same as "upper-level thrust" (上段突き jōdan-tsuki).

- Sword-taking (太刀取り tachitori) Being attacked with a sword or bokken, usually reserved for upper level practitioners.

- Knife-taking (短刀取り tantōtori) Being attacked with a tantō, usually a wooden one.

- Staff-taking (杖取り jōtori) Being attacked with a jō . Being attacked by any wooden staff is called bōtori(棒取り) or tsuetori(杖取り)

Beginners in particular often practice techniques from grabs, both because they are safer and because it is easier to feel the energy and lines of force of a hold than a strike. Some grabs are historically derived from being held while trying to draw a weapon; a technique could then be used to free oneself and immobilize or strike the attacker who is grabbing the defender.

- Single-hand grab (片手取り katate-dori) one hand grabs one wrist.

- Both-hands grab (諸手取り morote-dori) both hands grab one wrist. Same as "single hand double-handed grab" (片手両手取り katateryōte-dori)

- Both-hands grab (両手取り ryōte-dori) both hands grab both wrists. Same as "double single-handed grab" (両片手取り ryōkatate-dori).

- Shoulder grab (肩取り kata-dori) a shoulder grab. "Both-shoulders-grab" is ryōkata-dori (両肩取り). It is sometimes combined with an overhead strike as Shoulder grab face strike (肩取り面打ち kata-dori men-uchi).

- Chest grab (胸取り mune-dori or muna-dori) grabbing the (clothing of the) chest. Same as "collar grab" (襟取り eri-dori).

- Rear chokehold (後ろ裸絞 ushiro kubishime)

- Rear both shoulders grab (後ろ両肩取り ushiro ryokatori)

- Rear both wrists grab (後ろ手首取り ushiro tekubitori)

Techniques

When all attacks are considered, aikido has over 10,000 nameable techniques. Many aikido techniques derive from Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu, but some others were invented by Morihei Ueshiba. The precise terminology for some may vary between organisations and styles; what follows are the terms used by the Aikikai Foundation. (Note that despite the names of the first five techniques listed, they are not universally taught in numeric order.)[3] Several techniques (e.g. the "drop" throws) are also shared with judo, which can be considered a "cousin" of aikido due to their shared jujutsu background.

- First teaching (一教 ikkyō) ude osae (arm pin), a control using one hand on the elbow and one hand near the wrist which leverages uke to the ground.[4] This grip also applies pressure into the ulnar nerve at the wrist.

- Second teaching (二教 nikyō) kote mawashi, a pronating wristlock that torques the arm and applies painful nerve pressure. (There is an adductive wristlock or Z-lock in ura version.)

- Third teaching (三教 sankyō) kote hineri, a rotational wristlock that directs upward-spiraling tension throughout the arm, elbow and shoulder.

- Fourth teaching (四教 yonkyō) kote osae, a shoulder control similar to ikkyō, but with both hands gripping the forearm. The knuckles (from the palm side) are applied to the recipient's radial nerve against the periosteum of the forearm bone.[5]

- Fifth teaching (五教 gokyō) ude nobashi, visually similar to ikkyō, but with an inverted grip of the wrist, medial rotation of the arm and shoulder, and downward pressure on the elbow. Common in knife and other weapon take-aways.

- Sixth teaching (六教 rokkyō) also called Elbow arm-barring pressure (肘極め押さえ hiji kime osae)

- Arm-spraining second teaching (腕挫二教 ude hishigi nikkyo) an elbow lock generally used for knife thrusts or straight punches.

- Four-direction throw (四方投げ shihōnage) The hand is folded back past the shoulder, locking the shoulder joint.

- Forearm return (小手返し kotegaeshi) a supinating wristlock-throw that stretches the extensor digitorum.

- Breath throw (呼吸投げ kokyūnage) a loosely used term for various types of mechanically unrelated techniques, although they generally do not use joint locks like other techniques.[6]

Different types of kokyūnage include:

- ushironage 後ろ投げ the attacker falls backwards. Known as Tai no henkō in Yoshinkan

- tenkan tsugiashi 転換継ぎ足 rear pivot and then forward step

- irimi tenkan 入身転換

- irimi kaiten 入身回転

- kiri otoshi 切り落し "cutting drop"

- uki otoshi[7] 浮き落とし "floating drop"

- maki otoshi[8] 巻き落とし "rolling-up drop"

- hajiki goshi はじき腰 “flicking hip”

- katahiki-otoshi 肩ひき落とし “shoulder pulling drop”

- kata hiki hajiki goshi 肩ひきはじき腰 shoulder-pulling flicking hip

- suri-otoshi すり落とし “striking drop”

- tsurikomi-goshi 釣込腰 “lifting-pull hip”

- tsuri-goshi 釣腰 “pulling hip”

- kote-hineri koshi-nage 小手捻り腰投げ “forearm twist hip throw”

- Entering throw (入身投げ iriminage) throws in which tori moves through the space occupied by uke. The classic form superficially resembles a "clothesline" technique.

- Heaven-and-earth throw (天地投げ tenchinage) beginning with ryōte-dori; moving forward, tori' sweeps one hand low ("earth") and the other high ("heaven"), which unbalances uke so that he or she easily topples over.

- Hip throw (腰投げ koshinage) aikido's version of the hip throw. Tori drops his or her hips lower than those of uke, then flips uke over the resultant fulcrum.

- Figure-ten throw (十字投げ jūjinage) or figure-ten entanglement (十字絡み jūjigarami) a throw that locks the arms against each other (The kanji for "10" is a cross-shape: 十).[9]

- Rotary throw (回転投げ kaitennage) tori sweeps the arm back until it locks the shoulder joint, then uses forward pressure to throw.[10]

- Corner drop (隅落 Sumi otoshi)

- Arm extension throw (腕極め投げ udekimenage) from behind tori extends uke's arm slightly downwards and places the other arm under tori's upper arm, then moves whole body forward.

- Arm entanglement (腕絡み udegarami)

- Shoulder drop (背負落 Seoi otoshi)

- Body drop (体落 Tai otoshi)

- Large Hip (大腰 O goshi)

- Shoulder wheel (肩車 Kata guruma)

Yoshinkan terminology

The Yoshinkan school retains these Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu terms for the "first" through "fourth" techniques:

- 一ケ条 Ikkajo

- 二ケ条 Nikajo

- 三ケ条 Sankajo

- 四ケ条 Yonkajo

Implementations

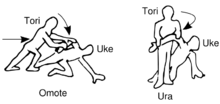

Aikido makes use of body movement (tai sabaki) to blend with uke. For example, an "entering" (irimi) technique consists of movements inward towards uke, while a "turning" (転換 tenkan) technique uses a pivoting motion.[11] Additionally, an "inside" (内 uchi) technique takes place in front of uke, whereas an "outside" (外 soto) technique takes place to his side; a "front" (表 omote) technique is applied with motion to the front of uke, and a "rear" (裏 ura) version is applied with motion towards the rear of uke, usually by incorporating a turning or pivoting motion. Finally, most techniques can be performed while in a seated posture (seiza). Techniques where both uke and tori are sitting are called suwari-waza, and techniques performed with uke standing and tori sitting are called hanmi handachi.[12]

Thus, from fewer than twenty basic techniques, there are thousands of possible implementations. For instance, ikkyō can be applied to an opponent moving forward with a strike (perhaps with an ura type of movement to redirect the incoming force), or to an opponent who has already struck and is now moving back to reestablish distance (perhaps an omote-waza version). Specific aikido kata are typically referred to with the formula "attack-technique(-modifier)".[13] For instance, katate-dori ikkyō refers to any ikkyō technique executed when uke is holding one wrist. This could be further specified as katate-dori ikkyō omote, referring to any forward-moving ikkyō technique from that grab.

Atemi (当て身) are strikes (or feints) employed during an aikido technique. Some view atemi as attacks against "vital points" meant to cause damage in and of themselves. For instance, Gōzō Shioda described using atemi in a brawl to quickly down a gang's leader.[14] Others consider atemi, especially to the face, to be methods of distraction meant to enable other techniques. A strike, whether or not it is blocked, can startle the target and break his or her concentration. The target may also become unbalanced in attempting to avoid the blow, for example by jerking the head back, which may allow for an easier throw.[12] Many sayings about atemi are attributed to Morihei Ueshiba, who considered them an essential element of technique.[15]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Homma, Gaku (1990). Aikido for Life. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. pp. 20–30. ISBN 978-1-55643-078-7.

- ↑ Japanese martial arts terms Two Cranes Aikido, Seattle, Washington

- ↑ Shifflett, C.M. (1999). Aikido Exercises for Teaching and Training. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-314-6.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Ikkyo". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 2014-08-26.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Yonkyo". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Kokyunage". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Barbara Britton - uki otoshi

- ↑ Barbara Britton Shidoin teaching maki-otoshi

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Juji Garami". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Kaitennage". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Amdur, Ellis. "Irimi". Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17.

- 1 2 Shioda, Gōzō (1968). Dynamic Aikido. Kodansha International. pp. 52–55. ISBN 978-0-87011-301-7.

- ↑ Taylor, Michael (2004). Aikido Terminology – An Essential Reference Tool In Both English and Japanese. Lulu Press. ISBN 978-1-4116-1846-6.

- ↑ Shioda, Gōzō; Payet, Jacques; Johnston, Christopher (2000). Aikido Shugyo: Harmony in Confrontation. Shindokan Books. ISBN 978-0-9687791-2-5.

- ↑ Scott, Nathan (2000). "Teachings of Ueshiba Morihei Sensei". Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-01.