Red-winged blackbird

| Red-winged blackbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Icteridae |

| Genus: | Agelaius |

| Species: | A. phoeniceus |

| Binomial name | |

| Agelaius phoeniceus (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

A. p. aciculatus | |

| |

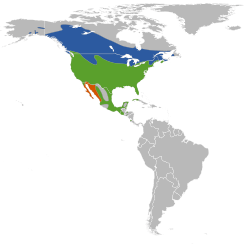

| Range of A. phoeniceus Breeding range Wintering range Year-round range | |

The red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) is a passerine bird of the family Icteridae found in most of North and much of Central America. It breeds from Alaska and Newfoundland south to Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, Mexico, and Guatemala, with isolated populations in western El Salvador, northwestern Honduras, and northwestern Costa Rica. It may winter as far north as Pennsylvania and British Columbia, but northern populations are generally migratory, moving south to Mexico and the southern United States. Claims have been made that it is the most abundant living land bird in North America, as bird-counting censuses of wintering red-winged blackbirds sometimes show that loose flocks can number in an excess of a million birds per flock and the full number of breeding pairs across North and Central America may exceed 250 million in peak years. It also ranks among the best-studied wild bird species in the world.[2][3][4][5][6] The red-winged blackbird is sexually dimorphic; the male is all black with a red shoulder and yellow wing bar, while the female is a nondescript dark brown. Seeds and insects make up the bulk of the red-winged blackbird's diet.

Taxonomy

The red-winged blackbird is one of 11 species in the genus Agelaius and is included in the family Icteridae, which is made up of passerine birds found in North and South America.[7] The red-winged blackbird was originally described as Oriolus phoeniceus by Linnaeus in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae,[8] but was later moved with the other American blackbirds to the genus Agelaius (Vieillot, 1816).[9] The genus name is Latin derived from Ancient Greek, agelaios, meaning "belonging to a flock". The specific epithet, phoeniceus, is from the Latin word meaning "deep red".[10]

There are a number of subspecies, some of doubtful status, which are mostly quite similar in appearance, but the bicolored blackbird A. p. gubernator of California and central Mexico – two isolated populations – is distinctive: the male lacks the yellow wing patch of the nominate race, and the female is much darker than the female nominate. The taxonomy of this form is little understood, with the relationships between these two populations, and between them and red-winged blackbirds, still unclear.[11] Despite the similar names, the red-winged blackbird is in a different family from the European redwing and the Old World common blackbird, which are thrushes (Turdidae).[7]

Description

The common name for the red-winged blackbird is taken from the mainly black adult male's distinctive red shoulder patches, or epaulets, which are visible when the bird is flying or displaying.[12] At rest, the male also shows a pale yellow wingbar. The female is blackish-brown and paler below. The female is smaller than the male, at 17–18 cm (6.7–7.1 in) long and weighing 41.5 g (1.46 oz), against his length of 22–24 cm (8.7–9.4 in) and weight of 64 g (2.3 oz).[13] The smallest females may weigh as little as 29 g (1.0 oz) whereas the largest males can weigh up to 82 g (2.9 oz).[14] Each wing can range from 8.1–14.4 cm (3.2–5.7 in), the tail measures 6.1–10.9 cm (2.4–4.3 in), the culmen measures 1.3–3.2 cm (0.51–1.26 in) and the tarsus measures 2.1 cm (0.83 in).[11]

Young birds resemble the female, but are paler below and have buff feather fringes. Both sexes have a sharply pointed bill. The tail is of medium length and is rounded. The eyes, bill, and feet are all black.[15]

The male is unmistakable except in the far west of the US, where the tricolored blackbird occurs. Males of that species have a darker red epaulet edged with white, not yellow. Females of tricolored, bicolored, red-shouldered and red-winged blackbirds can be difficult to identify in areas where more than one form occurs. In flight, when the field marks are not easily seen, red-winged can be distinguished from less closely related Icterids such as common grackle and brown-headed cowbird by its different silhouette and undulating flight.[11]

Distribution and habitat

The range of the red-winged blackbird stretches from southern Alaska to the Yucatan peninsula in the south, and from the western coast of California and Canada to the east coast of the continent. Red-winged blackbirds in the northern reaches of the range are migratory, spending winters in the southern United States and Central America. Migration begins in September or October, but occasionally as early as August. In western and central America, populations are generally non-migratory. [16]

The red-winged blackbird inhabits open grassy areas. It generally prefers wetlands, and inhabits both freshwater and saltwater marshes, particularly if cattail is present. It is also found in dry upland areas, where it inhabits meadows, prairies, and old fields.[16]

Behavior

Vocalisations

|

Cong-a-lee! call

One of several calls given by a male |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The calls of the red-winged blackbird are a throaty check and a high slurred whistle, terrr-eeee. The male's song, accompanied by a display of his red shoulder patches, is a scratchy oak-a-lee,[17] except that in many western birds, including bicolored blackbirds, it is ooPREEEEEom.[18] The female also sings, typically a scolding chatter chit chit chit chit chit chit cheer teer teer teerr.[11]

Predation

Virtually all of North America's raptors take adult or young red-winged blackbirds, even barn owls, which usually only take small mammals, and northern saw-whet owls, which are scarcely larger than a male red-winged. Accipiter hawks are among their most prolific predators and, locally, they are one of the preferred prey species of short-tailed hawks.[19] Crows, ravens, magpies and herons are occasionally predators of blackbird nests. Additional predators of blackbirds of all ages and their eggs include raccoons, mink, foxes and snakes, especially the rat snake. Marsh wrens destroy the eggs, at least sometimes drinking from them, and peck the nestlings to death.[20]

The red-winged blackbird aggressively defends its territory from other animals. It will attack much larger birds.[21] Males have been known to swoop at humans who encroach upon their nesting territory during breeding season.[22][23]

The maximum longevity of the red-winged blackbird in the wild is 15.8 years.[24]

Diet

The red-winged blackbird is omnivorous. It feeds primarily on plant materials, including seeds from weeds and waste grain such as corn and rice, but about a quarter of its diet consists of insects and other small animals, and considerably more so during breeding season.[25] It prefers insects, such as dragonflies, damselflies, butterflies, moths, and flies, but also consumes snails, frogs, eggs, carrion, worms, spiders, mollusks. The red-winged blackbird forages for insects by picking them from plants, or by catching them in flight.[15] In season, it eats blueberries, blackberries, and other fruit. These birds can be lured to backyard bird feeders by bread and seed mixtures and suet. In late summer and in autumn, the red-winged blackbird will feed in open fields, mixed with grackles, cowbirds, and starlings in flocks which can number in the thousands.[21]

Breeding

The red-winged blackbird nests in loose colonies. The nest is built in cattails, rushes, grasses, sedge, or in alder or willow bushes. The nest is constructed entirely by the female over the course of three to six days. It is a basket of grasses, sedge, and mosses, lined with mud, and bound to surrounding grasses or branches.[15] It is located 7.6 cm (3.0 in) to 4.3 m (14 ft) above water.[26]

A clutch consists of three or four, rarely five, eggs. Eggs are oval, smooth and slightly glossy, and measure 24.8 mm × 17.55 mm (0.976 in × 0.691 in).[26] They are pale bluish green, marked with brown, purple, and/or black, with most markings around the larger end of the egg. These are incubated by the female alone, and hatch in 11 to 12 days. Red-winged blackbirds are hatched blind and naked, but are ready to leave the nest 11 to 14 days after hatching.[13]

Red-winged blackbirds are polygynous, with territorial males defending up to 10 females. However, females frequently copulate with males other than their social mate and often lay clutches of mixed paternity. Pairs raise two or three clutches per season, in a new nest for each clutch.[13]

Predation of eggs and nestlings is quite common. Nest predators include snakes, mink, raccoons, and other birds, even as small as marsh wrens. The red-winged blackbird is occasionally a victim of brood parasites, particularly brown-headed cowbirds.[21] Since nest predation is common, several adaptations have evolved in this species. Group nesting is one such trait which reduces the risk of individual predation by increasing the number of alert parents. Nesting over water reduces the likelihood of predation, as do alarm calls. Nests, in particular, offer a strategic advantage over predators in that they are often well concealed in thick, waterside reeds and positioned at a height of one to two meters.[27] Males often act as sentinels, employing a variety of calls to denote the kind and severity of danger. Mobbing, especially by males, is also used to scare off unwanted predators, although mobbing often targets large animals and man-made devices by mistake. The brownish coloration of the female may also serve as an anti-predator trait in that it may provide camouflage for her and her nest while she is incubating.[16] Adults are vulnerable to a multitude of raptorial birds, at least 16 species have hunted them in North America, including all Accipiter hawks and falcons as well as most species of Buteo hawk and any owls that hunt in open or wetland habitats.[28][29]

Migration

Red-winged blackbirds that breed in the northern part of their range, i.e., Canada and border states in the United States, migrate south for the winter. However, populations near the Pacific and Gulf coasts of North America and those of Middle America are year-round resident.[2] Red-winged blackbirds live in both Northern U.S. and Canada, ranging from Yucatan Peninsula in the south to the southern part of Alaska.[2] These extensions account for the majority of the continent stretching from California’s Pacific coast and Canada to the eastern seaboard. Much of the populations within Middle America are non-migratory [30] During the fall, populations begin migrating towards Southern U.S. Movement of red-winged blackbirds can begin as early as August through October. Spring migration begins anywhere between mid-February to mid-May. Numerous birds from northern parts of the U.S., particularly the Great lakes, migrate nearly 1,200 km between their breeding season and winter [2] Winter territorial areas differ based on geographic location [30] Other populations that migrate year-round include those located in Middle America or in the western U.S. and Gulf Coast. Females typically migrate longer distances than males. These female populations located near the Great Lakes migrate nearly 230 km farther. Yearly-traveled females also migrate further than adult males, while also moving roughly the same distance as other adult females. Red-winged blackbirds migrate primarily during daytime. In general, males’ migration flocks arrive prior to females in the spring and after females in the fall.[2]

Territorial

Male red-winged blackbirds exhibit important territorial behaviors, most of which provides them with the necessary fidelity for many years to come. A few important factors for male red-winged blackbirds’ adherence to territories included food, hiding spaces from predators, types of neighbors, and reactions towards predators. Additionally, a study was done on site fidelity and movement patterns by Les D. Beletsky and Gordon H. Orians in 1987 which explained much of the males’ territorial behaviors once migrated and settled onto a territory of their own. Sufficient evidence had shown that males are committed to staying in their territory over a long period of time and are not more likely to change territories at a younger age due to limited experience of knowledge for success. Studies also showed that most of the males that were first-time movers to a new territory were between two and three years old. The majority of males that moved were young and inexperienced. Later on they had moved towards more available territories. If males had chosen to leave their territory for reproductive success, as an example, they would do so within a short distance. Males who moved shorter distances were more successful in reproducing than those who moved longer distances. Further studies showed that when males moved further away from their territories there was a decrease in probability of successfully fledging [31]

Relationship with humans

In winter, the species forage away from marshes, taking seeds and grain from open fields and agricultural areas. It is sometimes considered an agricultural pest.[11] Farmers have been known to use pesticides—such as parathion—in illegal attempts to control their populations.[32] In the United States, such efforts are illegal because no pesticide can be used on non-target organisms, or for any use not explicitly listed on the pesticide's label. However, the USDA has deliberately poisoned this species: in 2009, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service reported poisoning over 950,000 red-winged blackbirds in Texas and Louisiana.[33] This poisoning has been implicated as a potential cause of the decline of the rusty blackbird, a once abundant species that has declined 99% since the 1960s and has been recently listed as Threatened on the IUCN Red List.[34]

Like English, the indigenous languages of the bird's range describe it by its physical characteristics. In the Anishinaabe languages, an indigenous language group spoken throughout much of the bird's northeastern range, this bird's names are diverse. In the Oji-Cree language, the northernmost of the Anishinaabe languages, it is called jachakanoob, while the Ojibwa language spoken in Northwestern Ontario and into Manitoba ranging immediately south of the Oji-Cree's range, the bird is called jachakanoo (with the cognates cahcahkaniw (Swampy Cree), cahcahkaluw (coastal Southern East Cree), cahcahkayuw (inland Southern East Cree), cahcahkayow (Plains Cree)); the northern Algonquian languages classify the red-winged blackbird as a type of a junco or grackle, deriving the bird's name from their word for "spotted" or "marked". In the vast majority of the other Ojibwa language dialects, the bird is called memiskondinimaanganeshiinh, literally meaning "a bird with a very red damn-little shoulder-blade". However, in the Odawa language, an Anishinaabe language in southwestern Ontario and in Michigan, the bird is instead called either memeskoniinisi ("bird with a red [patch on its wing]") or memiskonigwiigaans ("[bird with a] wing of small and very red [patch]").[35] In N'syilxcn (Colville-Okanagan, Interior Salish language) the bird is known as ƛ̓kƛ̓aʕkək.[36]

In the Great Plains, the Lakota language, another indigenous language spoken throughout much of the bird's range, the bird is called wabloša ("wings of red"). Its songs are described in Lakota as tōke, mat'ā nī ("oh! that I might die"), as nakun miyē ("...and me"), as miš eyā ("me too!"), and as cap'cehlī ("a beaver's running sore").[37] And its name in nahuatl the Aztec idiom is "acolchichilli" that literally means "red shoulder".

Gallery

.jpg) Rear view of A. p. gubernator, the "bicolored blackbird", with no yellow border to the red patch

Rear view of A. p. gubernator, the "bicolored blackbird", with no yellow border to the red patch Note the golden coloration on the wing of this female red-winged blackbird

Note the golden coloration on the wing of this female red-winged blackbird

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Agelaius phoeniceus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yasukawa, Ken; Searcy, William A. (1995). A. Poole, ed. "Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus)". Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ McWilliams, Gerald M.; Brauning, Daniel W. (2000). The Birds of Pennsylvania. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801436435.

- ↑ Dolbeer, Richard A. (2008). "Blackbirds and their Biology". Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ Beletsky, L. (1996). The red-winged blackbird: the biology of a strongly polygynous songbird. Academic Press

- ↑ Holm, C. H. (1973). Breeding sex ratios, territoriality, and reproductive success in the Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus). Ecology, 356-365.

- 1 2 "Agelaius phoeniceus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ↑ Linnaeus, C (1766). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio duodecima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 161.

- ↑ Vieillot, L.P. (1816). Analyse D'Une Nouvelle Ornithologie Elementaire [A New Analysis of Elementary Ornithology] (in French). p. 33.

- ↑ Neff, John (1997). "Red-Winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus)". Northern State University. Archived from the original on 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jaramillo, Alvaro; Burke, Peter (1999). New World Blackbirds: The Icterids. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 258–269. ISBN 0-7136-4333-1.

- ↑ Peterson, Roger Tory (1980). A Field Guide to the Birds East of the Rockies. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 253. ISBN 5-550-55149-7.

- 1 2 3 Gough, Gregory (2003). "Agelaius phoeniceus". USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ↑ John B. Dunning Jr., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- 1 2 3 "Agelaius phoeniceus". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- 1 2 3 Rosenthal, A. (2004). "Agelaius phoeniceus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ↑ Peterson, Roger Tory (1999). A Field Guide to the Birds: Eastern and Central North America. HMCo Field Guides. p. 230. ISBN 0-395-96371-0.

- ↑ Sibley, David Allen (2000). The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred Knopf. p. 513. ISBN 0-679-45122-6.

- ↑ "The Barn Owl as a Red-Winged-Blackbird Predator in Northwestern Ohio" (PDF). Kb.osu.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ Kroodsma, Donald E.; Verner, Jared (1997). A. Poole, ed. "Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2013-03-03.

- 1 2 3 Terres, J. K. (1980). The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York, NY: Knopf. p. 938. ISBN 0-394-46651-9.

- ↑ "Chicago locals beware the birds". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Red-winged Blackbird". Assateague.com. 2005-05-25. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P.W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103–155. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

- ↑ Srygley, Robert B. & Kingsolver, Joel G. (1998). "Red-wing blackbird reproductive behaviour and the palatability, flight performance, and morphology of temperate pierid butterflies (Colias, Pieris, and Pontia)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 64 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1998.tb01532.x.

- 1 2 Harrison, Hal H. (1979). A Field Guide to Western Birds' Nests. Houghton Mifflin Field. p. 228. ISBN 0-618-16437-5.

- ↑ Cristol, Daniel. 1995. Early arrival, initiation of nesting, and social status: an experimental study of breeding female red-winged blackbirds. Behavioral Ecology. 6(1): 87-93.

- ↑ Orians, G. H. 1980. Some adaptations of marsh-nesting blackbirds. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ.

- ↑ Nero, R. W. 1984. Redwings. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- 1 2 Rosenthal, A. 2004. "Agelaius phoeniceus" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed October 31, 2014 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Agelaius_phoeniceus/.

- ↑ Beletsky, Les and Orians, Gordon. 1987. Territoriality among male red-winged blackbirds: I. Site fidelity and movement patterns. Behavioral ecology and sociobiology. 20: 21- 34.

- ↑ Stone, W.B.; Overmann S.R.; Okoniewski, J.C. (1984). "Intentional poisoning of birds with parathion" (PDF). The Condor. 86 (3): 333–336. doi:10.2307/1367004.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Martha (January 8, 2012). "Who Would Kill Blackbirds Intentionally?". Huffington Post. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Wells, Jeffrey V. (2007). Birder's Conservation Handbook: 100 North American Birds at Risk. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691123233.

- ↑ Weshki-ayaad, Lippert & Gambill. "Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary". Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Peterson, Sarah, Christopher Parkin and LaRae Wiley. Nsəlxcin 2 2006. interiorsalish.com

- ↑ Buechel, Eugene and Manhard, Paul (2002). Lakota Dictionary: Lakota-English / English-Lakota; New Comprehensive Edition. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1305-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Red-winged blackbird. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Agelaius phoeniceus |

- "Red-winged blackbird media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Red-winged blackbird – eNature.com

- Florida bird sounds including red-winged blackbird - Florida Museum of Natural History

- Red-winged blackbird photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)