Age disparity in sexual relationships

Age disparity in sexual relationships is the difference in ages of individuals in sexual relationships. Concepts of these relationships, including what defines an age disparity, have developed over time and vary among societies. Differences in age preferences for mates can stem from evolutionary mating strategies and age preferences in sexual partners may vary cross culturally. There are also alternative social theories for age differences in relationships as well as suggested reasons for 'alternative' age-hypogamous relationships. Age-disparity relationships have been documented for most of recorded history and have been regarded with a wide range of attitudes dependant on sociocultural norms and legal systems.

Statistics

| Age difference | Percentage of All Married Couples |

|---|---|

| Husband 20+ years older than wife | 1.0 |

| Husband 15–19 years older than wife | 1.6 |

| Husband 10–14 years older than wife | 4.8 |

| Husband 6–9 years older than wife | 11.6 |

| Husband 4–5 years older than wife | 13.3 |

| Husband 2–3 years older than wife | 20.4 |

| Husband and wife within 1 year | 33.2 |

| Wife 2–3 years older than husband | 6.5 |

| Wife 4–5 years older than husband | 3.3 |

| Wife 6–9 years older than husband | 2.7 |

| Wife 10–14 years older than husband | 1.0 |

| Wife 15–19 years older than husband | 0.3 |

| Wife 20+ years older than husband | 0.3 |

Data in Australia[2] and United Kingdom[3] show an almost identical pattern.

Relationships with age disparity of all kinds have been observed with both men and women as the older or younger partner. In various cultures, older men and younger women often seek one another for sexual or marital relationships.[4] Older women sometimes date younger men as well,[5] and in both cases wealth and physical attractiveness are often relevant. Nevertheless, because men generally are interested in women in their twenties, adolescent boys are generally sexually interested in women somewhat older than themselves.[6]

Most men marry women younger than they are; with the difference being between two and three years in Spain,[7] the UK reporting the difference to be on average about three years, and the US, two and a half.[8][9] The pattern was also confirmed for the rest of the world, with the gap being largest in Africa.[10] A study released in 2003 by the United Kingdom's Office for National Statistics concluded that the proportion of women in England and Wales marrying younger men rose from 15% to 26% between 1963 and 1998. Another study also showed a higher divorce rate as the age difference rose for when either the woman was older or the man was older.[11] [12] A 2008 study, however, concluded that the difference is not significant.[13][14]

In August 2010, Michael Dunn of the University of Wales Institute, Cardiff completed and released the results of a study on age disparity in dating. Dunn concluded that "Not once across all ages and countries ... did females show a preference for males significantly younger than male preferences for females" and that there was a "consistent cross-cultural preference by women for at least same-age or significantly older men". A 2003 AARP study reported that 34% of women over 39 years old were dating younger men.[15]

A 2011 study suggested that age disparity in marriage is positively correlated with decreased longevity, particularly for women, though married individuals still have longer lifespans than singles.[16]

Reasons for age disparity

Explanations for age disparity usually focus on either the rational choice model or the analysis of demographic trends in a society.[7] The rational choice model suggests that people look for partners who can provide for them in their life (bread-winners); as men traditionally earn more as they get older, women will therefore prefer older men.[7] This factor is diminishing as more women enter the labor force. The demographic trends are concerned with the gender ratio in the society, the marriage squeeze, and migration patterns.[7] Another explanation concerns cultural values: the higher the value placed in having children, the higher the age gap will be.[10]

As people have chosen to marry later, the age differences between couples have increased as well.[7][13]

In a Brown University study, it has been noted that the social structure of a country determines the age difference between spouses more than any other factor.[17] One of the concerns of relationships with age disparities in some cultures is a perceived difference between people of different age ranges. These differences may be sexual, financial or social in nature. Gender roles may complicate this even further. Socially, a society with a difference in wealth distribution between older and younger people may affect the dynamics of the relationship.[18]

Although the "cougar" theme, in which older women date much younger men, is often portrayed in the media as a widespread and established facet of modern Western culture, at least one academic study has found the concept to be a "myth". A British psychological study published in Evolution and Human Behavior in 2010 concluded that men and women, in general, continued to follow traditional gender roles when searching for mates. The study found that, as supported by other academic studies, most men preferred younger, physically attractive women, while most women, of any age, preferred successful, established men their age or older. The study found very few instances of older women pursuing much younger men and vice versa.[19]

Evolutionary perspective

Evolutionary approach

The evolutionary approach, based on the theories of Charles Darwin attempts to explain age disparity in sexual relationships in terms of natural selection and sexual selection.[20][21] Within sexual selection Darwin identified a further two mechanisms which are important factors in the evolution of sex differences (sexual dimorphism): intrasexual selection (involve competition with those of the same sex over access to mates) and intersexual choice (discriminative choice of mating partners).[22] An overarching evolutionary theory which can provide an explanation for the above mechanisms and strategies adopted by individuals which leads to age disparity in relationships is called Life History theory[23] which also includes Parental Investment Theory.[24] Life History theory posits that individuals have to divide energy and resources between activities (as energy and resources devoted to one task cannot be used for another task) and this is shaped by natural selection.[25] Parental Investment Theory refers to the value that is placed on a potential mate based on reproductive potential and reproductive investment. The theory predicts that preferred mate choices have evolved to focus on reproductive potential and reproductive investment of members of the opposite sex.[24] This theory predicts both intrasexual selection and intersexual choice due to differences in parental investment; typically there is competition among members of the lower investing sex (generally males) over the parental investment of the higher investing sex (generally females) who will be more selective in their mate choice. However, human males tend to have more parental investment compared to mammal males (although females still tend to have more parental investment).[26] Thus, both sexes will have to compete and be selective in mate choices. These two theories explain why natural and sexual selection acts slightly differently on the two sexes so that they display different preferences. For example, different age preferences may be a result of sex differences in mate values assigned to the opposite sex at those ages.[24]

A study conducted by David Buss investigated sex differences in mate preferences in 37 cultures with 10,047 participants. In all 37 cultures it was found that males preferred females younger than themselves and females preferred males older than themselves. These age preferences were confirmed in marriage records with males marrying females younger than them and vice versa.[27] A more recent study has supported these findings, conducted by Schwarz and Hassebrauck.[28] This study used 21,245 participants between 18 and 65 years of age who were not involved in a close relationship. As well as asking participants a number of questions on mate selection criteria, they also had to provide the oldest and youngest partner they would accept. It was found that for all ages males were willing to accept females that are slightly older than they are (on average 4.5 years older), but they accept females considerably younger than their own age (on average 10 years younger). Females demonstrate a complementary pattern, being willing to accept considerably older males (on average 8 years older) and were also willing to accept males slightly younger than themselves (on average 5 years younger). This is somewhat different to our close evolutionary relatives: chimpanzees. Male chimpanzees tend to prefer older females than younger and it is suggested that specific cues of female mate value are very different to humans.[29]

Male preference for younger females

Buss attributed the young age preference for females to the cues that youth has. In females, relative youth and physical attractiveness (which males valued more compared to females) demonstrated cues for fertility and high reproductive capacity.[27] Buss stated the specific age preference of around 25 years implied that fertility was a stronger ultimate cause of mate preference than reproductive value as data suggested that fertility peaks in females around mid-twenties.[27] From a life history theory perspective, females that have these cues, display they are more capable of reproductive investment.[30] This notion of preference of age due to peak fertility is supported by Kenrick, Keefe, Gabrielidis, and Cornelius's study which found that although teenage males would accept a mate slightly younger than themselves, there was a wider range of preference for ages above their own. Teenage males also report that their ideal mates would be several years older than themselves.[31] Buss and Schmitt[32] highlight that although long term mating relationships is common for humans, it is not characteristic of all mating relationships: there is both short term and long term mating relationships. Buss and Schmitt provided a Sexual Strategies Theory which predicts the two sexes have evolved distinct psychological mechanisms which underlie the strategies utilised for short and long term mating. This theory is directly relevant and compatible with the two already mentioned theories Life History and Parental Investment.[33][34] Males tend to appear orientated towards short term mating (greater desire for short term mates than women, prefer larger number of sexual partners and take less time to consent to sexual intercourse[34]) and this appears to solve a number of adaptive problems including using less resources to access a mate.[32] Although there is a number of reproductive advantages to short term mating, males still pursue long term mates and this is due to the possibility of monopolising a female's lifetime reproductive resources.[32] Consistent with findings, for both short term and long term mates, males prefer younger females (reproductively valuable).[32][35] Which demonstrates that regardless of short term or long term mating strategies are used males prefer younger females.

Female preference for older males

| Region | SMAM difference |

|---|---|

| Eastern Africa | 4.3 |

| Middle Africa | 6.0 |

| Northern Africa | 4.5 |

| Western Africa | 6.6 |

| Eastern Asia | 2.4 |

| South-Central Asia | 3.7 |

| South-Eastern Asia | 2.4 |

| Western Asia | 3.5 |

| Eastern Europe | 3.1 |

| Northern Europe | 2.3 |

| Southern Europe | 3.3 |

| Western Europe | 2.7 |

| Caribbean | 2.9 |

| Central America | 2.5 |

| South America | 2.9 |

| Northern America | 2.3 |

| Australia-New Zealand | 2.2 |

As they are the higher investing sex, females tend to be slightly more demanding when picking a mate (as predicted by parental investment theory).[26] They also tend to have a more difficult task of evaluating a male's reproductive value accurately based on physical appearance as age tends to have fewer constraints on a male's reproductive resources.[30] Buss attributed the older age preference to older males displaying characteristics of having high providing capacity)[27] such as status and resources.[28] In terms of short term and long term mating, females tend be orientated towards long term mating due to the costs incurred from short term mating.[32] Although some of these costs will be the same for males and females (risk of STIs and impairing long term mate value), the costs for women will be more severe due to paternity uncertainty (cues of multiple mates will be disfavoured by males).[32] In contrast to above, in short term females will tend to favour males that demonstrate physical attractiveness as this displays cues of ‘good genes’.[32] Cues of good genes tend to be typically associated with older males[37] such as facial masculinity and cheek-bone prominence.[38] Buss and Schmitt found similar female preferences for mates in long term which supports the notion that for long term relationships females prefer cues of high resource capacity, one of which is age.[32]

Cross-cultural differences

Cross-culturally, research has consistently supported the trend in which males prefer to mate with younger females, and females with older males.[22] In a cross-cultural study that covered 37 countries,[39] preferences for age differences were measured and research supported the theory that people prefer to marry close to the age when female fertility is at its highest (24–25 years). Analysing the results further we see that cross culturally; the average age females prefer to marry is 25.4 years old, and they prefer a mate 3.4 years older than themselves, therefore their preferred mate would be aged 28.8 years of age. Males however prefer to marry when they are 27.5 years old, and a female to be 2.7 years younger than themselves, yielding their preferred mate to be 24.8 years old. The results from the study therefore show that the mean preferred marriage age difference (3.04 years averaging male and female preferred age) corresponds very closely with the actual mean marriage age difference (2.99). The preferred age of females is 24.8 years and the actual average age females marry is 25.3 years old (and 28.2 for males) which actually falls directly on the age where females are most fertile, so the sexes have evolutionarily adapted mating preferences that maximise reproductivity.

The United Nations Marriage Statistics Department measures the SMAM difference[36] (Singulate Mean Age Marriage difference - the difference in average age at first marriage between men and women) across the main regions in the world (refer to Table. 1).

Larger than average age-gaps

| Country | SMAM difference | Legal Status of Polygamy |

|---|---|---|

| Cameroon a | 6.5 | Polygamous |

| Chad | 6.1 | Polygamous |

| Congo | 8.6 | Polygamous |

| Democratic Ep. Of The Congo | 8.2 | Polygamous |

| Sudan | 6.4 | Polygamous |

| Burkina Faso a | 8.6 | Polygamous |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 7.2 | No Longer Practiced |

| Gambia | 9.2 | Polygamous |

| Guinea a | 7.3 | Practiced but Illegal |

| Liberia | 6.5 | Not Criminalised |

| Mali | 7.5 | Polygamous |

| Mauritania | 7.7 | Polygamous |

| Niger | 6.3 | Polygamous |

| Nigeria | 6.9 | Polygamous |

| Senegal | 8.1 | Polygamous |

| Afghanistan | 7.5 | Polygamous |

| Bangladesh | 6.8 | Polygamous |

| Montserrat b | 8.3 | Unknown |

| Nauru | 7.3 | Prohibited |

| Mozambique | 8.6 | Not Criminalised |

However, in some regions of the world there is a substantially larger age gap between marriage partners in that males are much older than their wife (or wives). A theory that can explain this finding from an evolutionary perspective is the parasite-stress theory which explains that an increase of infectious disease can cause humans to evolve selectively according to these pressures. Evidence also shows that as disease risk gets higher, it puts a level of stress on mating selection and increases the use of polygamy.[40] In Table 2 we see the 20 countries with the largest age-gaps between spouses showing that 17/20 practice polygyny, and males ranging from 6.1 - 9.2 years older than their partners. In regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa the use of polygyny is commonly practiced as a consequence of; high sex-ratios (more males born per 100 females) and passing on heterozygous (diverse) genetics from different females onto offspring.[41] When disease is prevalent, if a male is producing offspring with a more diverse range of alleles, offspring will be more likely to withstand mortality from disease and continue the family line. Another reason that polygynous communities have larger age-gaps between spouses is that intrasexual competition for females increases as fewer females remain on the marriage market (with males having more than one wife each), therefore the competitive advantage values younger females due to their higher reproductive value.[42] As the competition for younger women becomes more common, we see the age in females' first marriage lower as older men seek younger and younger females.

Smaller than average age-gaps

Comparatively in Western societies such as the US and Europe we see a trend of smaller age-gaps between spouses, reaching its peak average in Southern Europe of 3.3 years. Using the same pathogen-stress model we see a lower prevalence of disease in these economically developed areas, and therefore a reduced stress on reproduction for survival. Additionally, it is common to see monogamous relationships widely in more modern societies as there are more women in the marriage market and polygamy is illegal throughout most of Europe and the United States.

As access to education increases worldwide, the age of marriage increases with it, with more of the youth staying in education for longer. The mean age of marriage in Europe is well above 25, and averaging at 30 in Nordic countries, however this may also be due to the increase of cohabitation in European countries. In some countries in Europe such as France, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Norway, Estonia, Finland and Denmark with 20–30% of women aged 20–34 cohabiting as opposed to legally marrying.[43] In addition to this with the gender pay gap decreasing, we see more women working equal hours (average of 40 hours in Europe and the US) to males and looking less for males with financial resources.[43]

Interestingly, in regions such as the Caribbean and Latin America we see a lower SMAM difference than expected, however there are also a large proportion of partners living in consensual unions; 24% in Brazil, 20% in Nicaragua and 18% in Dominican Republic.[44]

A 2011 study suggested that age disparity in marriage is positively correlated with decreased longevity, particularly for women, though married individuals still have longer lifespans than singles.[45]

Social perspectives

Social structural origin theory

Social Structural Origin Theory argues that the underlying cause of sex-differentiated behaviour is the concentration of men and women in differing roles in society. It has been argued that a reason gender roles are so prevalent in society is that the expectations of gender roles can become internalised in a person's self-concept and personality.[46] In a Brown University study, it has been noted that the social structure of a country determines the age difference between spouses more than any other factor.[47] In regards to mate selection, social structural theory supports the idea that individuals aim to maximise what they can provide in the relationship in an environment that is limiting their utilities through expected gender roles in society and marriage.[48]

It is thought that a trade-off or equilibrium is reached in regards to what each gender brings to the mating partnership and that this equilibrium is most likely to be reached with a trade-off of ages when selecting a mate.[49] Women are said to trade youth and physical attractiveness for economic security in their male partner.[50] This economic approach to choosing a partner ultimately depends on the marital or family system that is adopted by society. Women and men tend to seek a partner that will fit in with their society's sexual division of labour. For example, a marital system based on males being the provider and females the domestic worker, favours an age gap in the relationship. An older male is more likely to have more resources to provide to the family and a younger female is more likely to have less status or resources and so therefore will be these in a relationship, therefore lending the younger female to be more suited to the domestic worker role in the relationship.[48]

The rational choice model

The rational choice model also suggests that people look for partners who can provide for them in their life (bread-winners); as men traditionally earn more as they get older, women will therefore prefer older men.[51] This factor is diminishing as more women enter the labour force and the gender pay gap decreases.[51]

Age-hypogamy in relationships

Age-hypogamy defines a relationship where the woman is the older partner, the opposite of this being age-hypergamy.[52] Marriage between partners of roughly similar age is known as "age homogamy".[53]

Older female-younger male relationships are, relative to age-hypergamous relationships (older male-younger female), less researched in scientific literature.[52] Slang terms such as 'Cougar' have been used in films, TV shows and the media to depict older females with younger male mates. The picture often displays a stereotypical pairing of a divorced, middle-aged, white, affluent female dating a younger male with the relationship taking the form of a non-commitment arrangement between the partners.[54]

Although historically, age-hypogenous relationships have been very infrequent, recent US census data has shown an increase in age-hypogenous relationships from 6.4% in 2000 to 7.7% in 2012.[55]

There may be many reasons as to why age-hypogamous relationships are not very frequent. Sexual double standards in society may be one particular reason as to why women do not exhibit as many age-hypogamous relationships in comparison to age-hypergamous relationships.[52] Women also experience a double standard regarding the effects of ageing. In comparison to male sexuality, it considered that ageing in women is associated with decreased sex appeal and dating potential.[56]

There is debate in the literature as to what determines age-hypogamy in sexual relationships. A number of variables have been argued to influence the likelihood of women entering into an age-hypogamous relationship such as; racial or ethnic background, level of education, income, marital status, conservatism, age and number of sexual partners.[52] For example, it was found that in US Census data that African American communities showed an imbalanced sex ratio, whereby there were 100 African American woman for every 89 African American Males.[57] Support for this evidence was then found in regard to marriage, whereby it was shown that African American women were more likely to be in age-hypogamous or age-hypergamous marriages in comparison with White American women.[58] However, more recent evidence has found that women of other-race categories, outside of African or white American women were more likely to sleep with younger men,[52] showing that it is still unclear which, if any ethnic groups, are more likely to have age-hypogamous relationships.

Another example illustrating the varying literature surrounding age-hypogamous relationships is research indicating that a woman's marital status can influence her likelihood of engaging in age-hypogamous relationships. It has been found that married women are less likely to be partnered with a younger male compared to non-married women[59] in comparison to more recent findings, which provides evidence to suggest that previously married women are more likely to engage in an age-hypogamous sexual relationship compared to women who are married or who have never been married.[52]

Despite social views depicting age-hypogamous relationships as short lived and fickle, recent research published by Psychology of Women Quarterly has found that women in age-hypogamous relationships are more satisfied and the most committed in their relationships compared to younger women or similarly aged partners.[60] It has also been suggested that male partners to an older female partner may engage in age-hypogamous relationships due to findings that men choose beauty over age. A recent study found that when shown pictures of women of ages ranging from 20–45 with different levels of attractiveness, regardless of age, males chose the more attractive individuals as long term partners.[61]

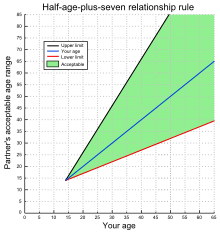

The "half-your-age-plus-seven" rule

The "never date anyone under half your age plus seven" rule is a rule of thumb sometimes used to prejudge whether an age difference is socially acceptable.[62][63][64] Although the origin of the rule is unclear, it is sometimes considered to have French origin.[62]

In earlier sources, the rule had a different interpretation than in contemporary culture, as it was understood as a formula to calculate ideal age for the bride, instead of a lower limit for the suitable age. Max O'Rell's Her Royal Highness Woman from 1901 gives the rule in the format "A man should marry a woman half his age, plus seven."[65] Similar interpretation is also present in the 1951 play The Moon Is Blue by F. Hugh Herbert.[66]

The half-your-age-plus seven rule also appears in John Fox, Jr.'s The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come in 1903,[67] in American newspapers in 1931, attributed to Maurice Chevalier,[68] and in The Autobiography of Malcolm X.[69]

In modern times this rule has been criticised as being more accurate for men than women, and for allowing a greater maximum age for a woman's partner later in her life than is actually socially acceptable.[70]

Slang terms

The age disparity between two partners is typically met with some disdain in industrialized nations, and various derogatory terms for participants have arisen in the vernacular.

In English-speaking countries, where financial disparity, and an implicit money-for-companionship exchange, is perceived as central to the relationship, the elder of the two partners (perceived as the richer) is often called a "sugar daddy" or "sugar mama" depending on gender. The younger of the two is similarly called the sugar baby. In extreme cases, a person who marries into an extremely wealthy family can be labelled a gold digger, especially in cases where the wealthy partner is of extreme age and/or poor health; this term often describes women but can be applied to either gender.[71]

An attractive younger woman pursued by a wealthy man who is perceived as wanting her only for her looks may be called a trophy wife.[72] The opposite term trophy husband does not have an agreed upon use, but is becoming more common in usage: some will use the term to refer to the attractive stay-at-home husband of a much more famous woman; whereas some will use it to refer to the husband of a trophy wife, as he is her trophy due to the wealth and prestige he brings her. In the latter case, the term trophy is broadened to include any substantial difference in power originating from physical looks, wealth and/or status.

It should be noted that the trophy label is often perceived as objectifying the partner, with or without the partner's implicit consent.

Where the primary perceived reason for a relationship with a significant age difference is sexual, many gender-specific terms have become popular in English-speaking cultures. A woman of middle to elderly age who pursues younger men is a cougar or puma, and a man in a relationship with an older woman is often called a boytoy, toyboy, himbo, or cub. In reverse, the terms rhino, trout and manther (a play on the panther term for women) are generally used to label an older man pursuing younger women, and the younger woman in such a relationship may be called a kitten or panther.[73] If the woman is extremely young (just over, or possibly under, the legal age of consent), the man may be labelled a cradle-robber. An older term for any licentious or lascivious man is a lecher, and that term and its shortening of lech have become common to describe an elderly man who makes passes at much younger women, especially caretakers and in other cases where the advances are unwanted.

While often intended to be derogatory, some of these terms are often used by the participants in the relationship to describe themselves and each other. Some are viewed as mildly self-deprecating, others as neutral or even complimentary terms, much like individuals stereotypically referred to as nerds, geeks, or jocks have often come to own those terms as a source of pride in their identity. When the attraction between two people of significantly different ages seems genuinely romantic, the terms are often used playfully, especially as one or the other of the partners ages in to a particular term.

See also

- Homogamy (sociology)

- Hypergamy

- Life history theory

- Mate choice

- Parental investment

- Polygamy

- Sexual evolution

- Sexual selection in humans

- Gerontophilia

- Ephebophilia

References

- ↑ "Married Couple Family Groups, By Presence Of Own Children Under 18, And Age, Earnings, Education, And Race And Hispanic Origin Of Both Spouses". U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2013 Annual Social and Economic Supplement. 2013.

- ↑ "Distribution of the Difference in Age Between Couples at First Marriage(a), 1974 and 1995". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Ben Wilson and Steve Smallwood. "Age differences at marriage and divorce" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Kenrick, Douglas; Keefe, Richard; Gabrielidis, Cristina; Comelius, Jeffrey (1996). "Adolescents' Age Preferences for Dating Partners: Support for an Evolutionary Model of Life-History Strategies". Child Development. 67 (4): 1499–1511. PMID 8890497. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01810.x.

- ↑ Hakim, Catherine (2010). "Erotic Capital". European Sociological Review. 26 (5): 499–518. doi:10.1093/esr/jcq014.

- ↑ Antfolk, Jan; Salo, Benny; Alanko, Katarina; Bergen, Emilia; Corander, Jukka; Sandnabba, N. Kenneth; Santtila, Pekka (2015). "Women's and men's sexual preferences and activities with respect to the partner's age: evidence for female choice". Evolution & Human Behavior. 36 (1): 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.09.003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Long Term Trends in Marital Age Homogamy Patterns: Spain, 1922-2006". Cairn.info. 2009-08-21. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ↑ Wardrop, Murray (2009-06-02). "Men 'live longer' if they marry a younger woman". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ Wang, Wendy (2012-02-16). "The Rise of Intermarriage - Page 3 | Pew Social & Demographic Trends - Page 3". Pewsocialtrends.org. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- 1 2 Zhang, Xu; Polachek, Solomon W. (October 2007). "The Husband-Wife Age Gap at First Marriage: A Cross-Country Analysis". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.187.147

.

. - ↑ "More women marrying younger men". BBC News. 12 December 2003.

- ↑ "The bigger the age gap, the shorter the marriage". New York Post. 11 November 2014.

- 1 2 Ben Wilson and Steve Smallwood, "Age differences at marriage and divorce", Population Trends 132, Summer 2008, Office for National Statistics

- ↑ Strauss, Delphine (2008-06-26). "Age gap is no risk to marriages, ONS says". FT.com. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ↑ Moss, Hilary (August 22, 2010). "New Study Claims No Cougar Trend, Dating Websites Attempt To Show Otherwise". Huffington Post. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ↑ Ian Sample. "Marrying a younger man increases a woman's mortality rate | Science". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ↑ Casterline, John; Williams, Lindy; McDonald, Peter (1986). "The Age Difference Between Spouses: Variations among Developing Countries". Population Studies. 40 (3): 353. doi:10.1080/0032472031000142296.

- ↑ Luke, N. (2005). "Confronting the 'Sugar Daddy' Stereotype: Age and Economic Asymmetries and Risky Sexual Behavior in Urban Kenya". International Family Planning Perspectives. 31 (1): 6–14. JSTOR 3649496. PMID 15888404. doi:10.1363/3100605.

- ↑ Alleyne, Richard, "The 'Cougar' concept: older women preying on younger men is a myth, claim scientists", The Telegraph, 19 August 2010

- ↑ Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man. The Great Books of the Western World, 49, 320.

- ↑ Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of the species by natural selection

- 1 2 Geary, D. C., Vigil, J., & Byrd‐Craven, J. (2004). Evolution of human mate choice. Journal of sex research, 41(1), 27–42.

- ↑ Yampolsky, Lev Y(Jul 2003) Life History Theory. In: eLS. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester. http://www.els.net doi:10.1038/npg.els.0003219

- 1 2 3 Robert, T. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. Sexual Selection & the Descent of Man, Aldine de Gruyter, New York, 136–179.

- ↑ Stearns, S. C. (2000). Life history evolution: successes, limitations, and prospects. Naturwissenschaften, 87(11), 476–486.

- 1 2 Bjorklund, D. F., & Shackelford, T. K. (1999). Differences in parental investment contribute to important differences between men and women. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(3), 86–89.

- 1 2 3 4 Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and brain sciences, 12(01), 1–14.

- 1 2 Schwarz, S., & Hassebrauck, M. (2012). Sex and age differences in mate-selection preferences. Human Nature, 23(4), 447–466.

- ↑ Muller, M. N., Thompson, M. E., & Wrangham, R. W. (2006). Male chimpanzees prefer mating with old females. Current Biology, 16(22), 2234–2238.

- 1 2 Buss, D. M., & Barnes, M. (1986). Preferences in human mate selection. Journal of personality and social psychology, 50(3), 559.

- ↑ Kenrick, D., Keefe, R., Gabrielidis, C., & Cornelius, J. (1996). Adolescents' Age Preferences for Dating Partners: Support for an Evolutionary Model of Life-History Strategies. Child Development, 67(4), 1499–1511.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: an evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological review, 100(2), 204.

- ↑ Kenrick, D. T., & Keefe, R. C. (1992). Age preferences in mates reflect sex differences in human reproductive strategies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 15(01), 75–91

- 1 2 Schmitt, D. P., Shackelford, T. K., & Buss, D. M. (2001). Are men really more'oriented'toward short-term mating than women? A critical review of theory and research. Psychology, Evolution & Gender, 3(3), 211–239.

- ↑ Young, J. A., Critelli*, J. W., & Keith, K. W. (2005). Male age preferences for short-term and long-term mating. Sexualities, Evolution & Gender, 7(2), 83–93.

- 1 2 3 https://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/worldmarriage/worldmarriage.htm

- ↑ Li, N. P., & Kenrick, D. T. (2006). Sex similarities and differences in preferences for short-term mates: what, whether, and why. Journal of personality and social psychology, 90(3), 468.

- ↑ "Facial attractiveness, symmetry and cues of good genes". Scheib, J. E., Gangestad, S. W., & Thornhill, R. (1999). Facial attractiveness, symmetry and cues of good genes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 266(1431), 1913–1917.

- ↑ "Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures.". Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and brain sciences, 12(01), 1–14.

- ↑ "Marriage systems and pathogen stress in human societies.". Low, B. S. (1990). Marriage systems and pathogen stress in human societies. American Zoologist, 30(2), 325–340.

- ↑ "Polygynists and their wives in sub-Saharan Africa". Timeus I.M., Reynar A. (1998). Polygynists and their wives in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of five Demographic and Health Surveys. Population Studies, 52:145–162.

- ↑ "The puzzle of monogamous marriage.". Henrich, J., Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (2012). The puzzle of monogamous marriage. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367(1589), 657–669. – via http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0290.

- 1 2 "World's Women Report 2015" (PDF).

- ↑ "World's Women Report 2010" (PDF).

- ↑ Ian Sample. "Marrying a younger man increases a woman's mortality rate | Science". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ↑ Feingold, A (1994). "Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 116: 429–456.

- ↑ Luke, N (2005). "Confronting the 'Sugar Daddy' Stereotype: Age and Economic Asymmetries and Risky Sexual Behavior in Urban Kenya". International Family Planning Perspectives.

- 1 2 Eagly, Alice. H.; Wood, Wendy (1999). "The Origins of Sex Differences in Human Behavior: Evolved Dispositions Versus Social roles". American Psychologist. 54: 408–423.

- ↑ Beck, G. S. (1976). The economic approach to human behaviour. Chicago: Chicago Press.

- ↑ Brehm, S. S. (1985). Intimate relationships. Random House.

- 1 2 Casterline, John; Williams, Lindy; McDonald, Peter (1986). "The Age Difference Between Spouses: Variations among Developing Countries". Population Studies. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Alarie, Milaine; Carmichael, Jason. T. (2015). "The "Cougar" Phenomenon: An Examination of the Factors That Influence Age-Hypogamous Sexual Relationships Among Middle-Aged Women". Journal of Marriage and Family. 77: 1250–1265.

- ↑ "Long Term Trends in Marital Age Homogamy Patterns: Spain, 1922–2006". Cairn.info. 2009-08-21. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ↑ Kaklamanidou, N. (2012). "Pride and prejudice: Celebrity versus fictional cougars". Celebrity Studies. 3: 78–89.

- ↑ Bureau of the Census (2012). Current Population Survey: Annual social and economic supplement. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Friedman, A.; Weinberg, H.; Pines, A.M. (1998). "Sexuality and motherhood: Mutually exclusive in perception of women". Sex Roles. 38: 781–800.

- ↑ . Bureau of the Census, U. S. (2002). Race and Hispanic or Latino origin by age and sex for the United States: 2000. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Atkinson, M. P.; Glass, B. L. (1985). "Marital age heterogamy and homogamy, 1900 to 1980.". Journal of Marriage and the Family. 47: 685–691.

- ↑ Darroch, J. E.; Landry, D.J.; Oslak, S. (1999). "Age differences between sexual partners in the United States". Family Planning Perspectives. 31: 160–167.

- ↑ "The Science Behind The Cougar-Chasing 20-Something". Medical Daily. 2015-01-30. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- ↑ "BBC News | HEALTH | The lure of the older woman". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- 1 2 Rodale, Inc. (April 2007). Best Life. Rodale, Inc. p. 21. ISSN 1548-212X.

- ↑ Hans Erikson (1964). The Rhythm of the Shoe. Jacaranda Press. p. 87.

- ↑ Belisa Vranich & Laura Grashow (2008). Dating the Older Man. Adams Media. p. 16.

- ↑ Max O'Rell. "Chapter IV: Advice to the Man Who Wants to Marry". Her Royal Highness Woman. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ↑ Moon Is blue.: [A play]: Herbert, Frederick Hugh at Internet Archive

- ↑ John Fox (1903). The little shepherd of Kingdom Come. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 222.

- ↑ "Maurice Chevalier says....plus seven years". Detroit News item reprinted in Oakland (CA) News, 27 August 1931.

- ↑ Malcolm X & Alex Haley (1965). The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

- ↑ "The Half-Your-Age-Plus-Seven Rule: Does It Really Work?". Psychology Today. 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ Jimenez, Daniel (1998-12-10). "Meet and marry the rich". BankRate.com.

- ↑ Berman, Phyllis (1997-11-17). ""Honey, am I a trophy wife?"".

- ↑ http://www.internetslang.com/PANTHER-meaning-definition.asp

Further reading

- Alarie, Milaine; Carmichael, Jason. T. (2015). "The "Cougar phenomenon: An Examination of the Factord That Influence Age-Hypogamous Sexual Relationships Among Middle-Aged Women". Journal of Marriage and Family. 77: 1250–1265

- Buss, D. M. (2015). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Foundation. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and brain sciences, 12(01), 1–14.

- Buss, D. M., & Barnes, M. (1986). Preferences in human mate selection. Journal of personality and social psychology, 50(3), 559.

- Polygynists and their wives in sub-Saharan Africa". Timeus I.M., Reynar A. (1998). Polygynists and their wives in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of five Demographic and Health Surveys. Population Studies, 52:145–162.