Afroasiatic languages

| Afroasiatic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Horn of Africa, North Africa, Sahel, West Asia |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Afroasiatic |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | afa |

| Glottolog | afro1255[2] |

|

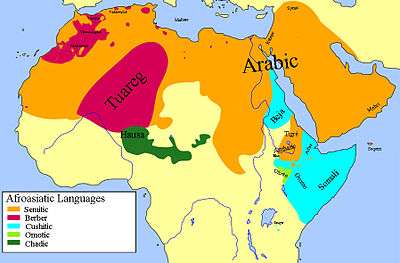

Distribution of the Afro-Asiatic languages. Yellow signifies areas without any languages in that family. | |

Afroasiatic (Afro-Asiatic), also known as Afrasian and traditionally as Hamito-Semitic (Chamito-Semitic),[3] is a large language family of several hundred related languages and dialects. It comprises about 300 or so living languages and dialects, according to the 2009 Ethnologue estimate.[4] It includes languages spoken predominantly in West Asia, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and parts of the Sahel.

Afroasiatic languages have over 350 million native speakers, the fourth largest number of any language family (after Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan and Niger–Congo).[5] The phylum has six branches: Berber, Chadic, Cushitic, Egyptian, Omotic and Semitic.

By far the most widely spoken Afroasiatic language is Arabic. It is also the most widely spoken language within the Semitic branch, and includes Modern Standard Arabic and spoken colloquial varieties. Arabic has around 290 million native speakers, who are concentrated primarily in West Asia, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and Malta.[6]

Other widely spoken Afroasiatic languages include:

- Hausa (Chadic branch), the dominant language of northern Nigeria and southern Niger, spoken as a first language by 35 million people and used as a lingua franca by another 20 million across West Africa and the Sahel.[7]

- Central Atlas Tamazight (Berber branch), spoken in Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, northern Mali, northern Niger, and Egypt by around 25 to 35 million people.

- Oromo (Cushitic branch), spoken in Ethiopia and Kenya by around 33 million people total.

- Amharic (Semitic branch), spoken in Ethiopia, with over 25 million native speakers in addition to millions of other Ethiopians speaking it as a second language.

- Somali (Cushitic branch), spoken by 15.5 million people in Greater Somalia.

- Hebrew (Semitic branch), spoken by around 9 million people worldwide.[8]

- Tigrinya (Semitic branch), spoken by around 6.9 million people in Eritrea and Ethiopia.

- Neo-Aramaic languages (Semitic branch), spoken by about 550,000 people worldwide.[9] This is not just one language — It includes a number of subdivisions, with Assyrian Neo-Aramaic being the most spoken variety (232,300).[10]

In addition to languages spoken today, Afroasiatic includes several important ancient languages, such as Ancient Egyptian, Akkadian, Biblical Hebrew, and Old Aramaic. It is uncertain when or where the original homeland of the Afroasiatic family existed. Proposed locations include North Africa, the Horn of Africa, the Eastern Sahara, and the Levant.

Etymology

During the early 1800s, linguists grouped the Berber, Cushitic and Egyptian languages within a "Hamitic" phylum, in acknowledgement of these languages' genetic relation with each other and with those in the Semitic phylum.[11] The terms "Hamitic" and "Semitic" were etymologically derived from the Book of Genesis, which describes various Biblical tribes descended from Ham and Shem, two sons of Noah.[12] By the 1860s, the main constituent elements within the broader Afroasiatic family had been worked out.[11]

The scholar Friedrich Müller introduced the name "Hamito-Semitic" for the entire family in his Grundriss der Sprachwissenschaft (1876).[13] Maurice Delafosse (1914) later coined the term "Afroasiatic" (often now spelled "Afro-Asiatic"). However, it did not come into general use until Joseph Greenberg (1950) formally proposed its adoption. In doing so, Greenberg sought to emphasize the fact that Afroasiatic spanned the continents of both Africa and Asia.[13]

Individual scholars have also called the family "Erythraean" (Tucker 1966) and "Lisramic" (Hodge 1972). In lieu of "Hamito-Semitic", the Russian linguist Igor Diakonoff later suggested the term "Afrasian", meaning "half African, half Asiatic", in reference to the geographic distribution of the family's constituent languages.[14]

The term "Hamito-Semitic" remains in use in the academic traditions of some European countries.

Distribution and branches

The Afroasiatic language family is usually considered to include the following branches:

Although there is general agreement on these six families, there are some points of disagreement among linguists who study Afroasiatic. In particular:

- The Omotic language branch is the most controversial member of Afroasiatic, because the grammatical formatives that most linguists have given greatest weight in classifying languages in the family "are either absent or distinctly wobbly" (Hayward 1995). Greenberg (1963) and others considered it a subgroup of Cushitic, whereas others have raised doubts about it being part of Afroasiatic at all (e.g. Theil 2006).[1]

- The Afroasiatic identity of Ongota is also broadly questioned, as is its position within Afroasiatic among those who accept it, due to the "mixed" appearance of the language and a paucity of research and data. Harold Fleming (2006) proposes that Ongota constitutes a separate branch of Afroasiatic.[15] Bonny Sands (2009) believes the most convincing proposal is by Savà and Tosco (2003), namely that Ongota is an East Cushitic language with a Nilo-Saharan substratum. In other words, it would appear that the Ongota people once spoke a Nilo-Saharan language but then shifted to speaking a Cushitic language but retained some characteristics of their earlier Nilo-Saharan language.[1]

- Beja is sometimes listed as a separate branch of Afroasiatic but is more often included in the Cushitic branch, which has a high degree of internal diversity.

- Whether the various branches of Cushitic actually form a language family is sometimes questioned, but not their inclusion in Afroasiatic itself.

- There is no consensus on the interrelationships of the five non-Omotic branches of Afroasiatic (see § Subgrouping below). This situation is not unusual, even among long-established language families: there are also many disagreements concerning the internal classification of the Indo-European languages, for instance.

- Meroitic has been proposed as an unclassified Afroasiatic language, because it shares the phonotactics characteristic of the family, but there is not enough evidence to secure a classification.

Classification history

In the 9th century, the Hebrew grammarian Judah ibn Quraysh of Tiaret in Algeria was the first to link two branches of Afroasiatic together; he perceived a relationship between Berber and Semitic. He knew of Semitic through his study of Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic.

In the course of the 19th century, Europeans also began suggesting such relationships. In 1844, Theodor Benfey suggested a language family consisting of Semitic, Berber, and Cushitic (calling the latter "Ethiopic"). In the same year, T.N. Newman suggested a relationship between Semitic and Hausa, but this would long remain a topic of dispute and uncertainty.

Friedrich Müller named the traditional Hamito-Semitic family in 1876 in his Grundriss der Sprachwissenschaft ("Outline of Linguistics"), and defined it as consisting of a Semitic group plus a "Hamitic" group containing Egyptian, Berber, and Cushitic; he excluded the Chadic group. It was the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius (1810–1884) who restricted Hamitic to the non-Semitic languages in Africa, which are characterized by a grammatical gender system. This "Hamitic language group" was proposed to unite various, mainly North-African, languages, including the Ancient Egyptian language, the Berber languages, the Cushitic languages, the Beja language, and the Chadic languages. Unlike Müller, Lepsius considered that Hausa and Nama were part of the Hamitic group. These classifications relied in part on non-linguistic anthropological and racial arguments. Both authors used the skin-color, mode of subsistence, and other characteristics of native speakers as part of their arguments that particular languages should be grouped together.[16]

In 1912, Carl Meinhof published Die Sprachen der Hamiten ("The Languages of the Hamites"), in which he expanded Lepsius's model, adding the Fula, Maasai, Bari, Nandi, Sandawe and Hadza languages to the Hamitic group. Meinhof's model was widely supported into the 1940s.[16] Meinhof's system of classification of the Hamitic languages was based on a belief that "speakers of Hamitic became largely coterminous with cattle herding peoples with essentially Caucasian origins, intrinsically different from and superior to the 'Negroes of Africa'."[17] But, in the case of the so-called Nilo-Hamitic languages (a concept he introduced), it was based on the typological feature of gender and a "fallacious theory of language mixture." Meinhof did this although earlier work by scholars such as Lepsius and Johnston had substantiated that the languages which he would later dub "Nilo-Hamitic" were in fact Nilotic languages, with numerous similarities in vocabulary to other Nilotic languages.[18]

Leo Reinisch (1909) had already proposed linking Cushitic and Chadic, while urging their more distant affinity with Egyptian and Semitic. However, his suggestion found little acceptance. Marcel Cohen (1924) rejected the idea of a distinct "Hamitic" subgroup, and included Hausa (a Chadic language) in his comparative Hamito-Semitic vocabulary. Finally, Joseph Greenberg's 1950 work led to the widespread rejection of "Hamitic" as a language category by linguists. Greenberg refuted Meinhof's linguistic theories, and rejected the use of racial and social evidence. In dismissing the notion of a separate "Nilo-Hamitic" language category in particular, Greenberg was "returning to a view widely held a half century earlier." He consequently rejoined Meinhof's so-called Nilo-Hamitic languages with their appropriate Nilotic siblings.[11] He also added (and sub-classified) the Chadic languages, and proposed the new name Afroasiatic for the family. Almost all scholars have accepted this classification as the new and continued consensus.

Greenberg's model was fully developed in his book The Languages of Africa (1963), in which he reassigned most of Meinhof's additions to Hamitic to other language families, notably Nilo-Saharan. Following Isaac Schapera and rejecting Meinhof, he classified the Hottentot language as a member of the Central Khoisan languages. To Khoisan he also added the Tanzanian Hadza and Sandawe, though this view remains controversial since some scholars consider these languages to be linguistic isolates.[19][20] Despite this, Greenberg's model remains the basis for modern classifications of languages spoken in Africa, and the Hamitic category (and its extension to Nilo-Hamitic) has no part in this.[20]

Since the three traditional branches of the Hamitic languages (Berber, Cushitic and Egyptian) have not been shown to form an exclusive (monophyletic) phylogenetic unit of their own, separate from other Afroasiatic languages, linguists no longer use the term in this sense. Each of these branches is instead now regarded as an independent subgroup of the larger Afroasiatic family.[21]

In 1969, Harold Fleming proposed that what had previously been known as Western Cushitic is an independent branch of Afroasiatic, suggesting for it the new name Omotic. This proposal and name have met with widespread acceptance.

Several scholars, including Harold Fleming and Robert Hetzron, have since questioned the traditional inclusion of Beja in Cushitic.

Glottolog does not accept that the inclusion or even unity of Omotic has been established, nor that of Ongota or the unclassified Kujarge. It therefore splits off the following groups as small families: South Omotic, Mao, Dizoid, Gonga–Gimojan (North Omotic apart from the preceding), Ongota, Kujarge.

Subgrouping

| Greenberg (1963) | Newman (1980) | Fleming (post-1981) | Ehret (1995) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(excludes Omotic) |

|

|

| Orel & Stobova (1995) | Diakonoff (1996) | Bender (1997) | Militarev (2000) |

|

(excludes Omotic) |

|

|

Little agreement exists on the subgrouping of the five or six branches of Afroasiatic: Semitic, Egyptian, Berber, Chadic, Cushitic, and Omotic. However, Christopher Ehret (1979), Harold Fleming (1981), and Joseph Greenberg (1981) all agree that the Omotic branch split from the rest first.

Otherwise:

- Paul Newman (1980) groups Berber with Chadic and Egyptian with Semitic, while questioning the inclusion of Omotic in Afroasiatic. Rolf Theil (2006) concurs with the exclusion of Omotic, but does not otherwise address the structure of the family.[22]

- Harold Fleming (1981) divides non-Omotic Afroasiatic, or "Erythraean", into three groups, Cushitic, Semitic, and Chadic-Berber-Egyptian. He later added Semitic and Beja to Chadic-Berber-Egyptian and tentatively proposed Ongota as a new third branch of Erythraean. He thus divided Afroasiatic into two major branches, Omotic and Erythraean, with Erythraean consisting of three sub-branches, Cushitic, Chadic-Berber-Egyptian-Semitic-Beja, and Ongota.

- Like Harold Fleming, Christopher Ehret (1995: 490) divides Afroasiatic into two branches, Omotic and Erythrean. He divides Omotic into two branches, North Omotic and South Omotic. He divides Erythrean into Cushitic, comprising Beja, Agaw, and East-South Cushitic, and North Erythrean, comprising Chadic and "Boreafrasian." According to his classification, Boreafrasian consists of Egyptian, Berber, and Semitic.

- Vladimir Orel and Olga Stolbova (1995) group Berber with Semitic and Chadic with Egyptian. They split up Cushitic into five or more independent branches of Afroasiatic, viewing Cushitic as a Sprachbund rather than a language family.

- Igor M. Diakonoff (1996) subdivides Afroasiatic in two, grouping Berber, Cushitic, and Semitic together as East-West Afrasian (ESA), and Chadic with Egyptian as North-South Afrasian (NSA). He excludes Omotic from Afroasiatic.

- Lionel Bender (1997) groups Berber, Cushitic, and Semitic together as "Macro-Cushitic". He regards Chadic and Omotic as the branches of Afroasiatic most remote from the others.

- Alexander Militarev (2000), on the basis of lexicostatistics, groups Berber with Chadic and both more distantly with Semitic, as against Cushitic and Omotic. He places Ongota in South Omotic.

Position among the world's languages

Afroasiatic is one of the four major language families spoken in Africa identified by Joseph Greenberg in his book The Languages of Africa (1963). It is one of the few whose speech area is transcontinental, with languages from Afroasiatic's Semitic branch also spoken in the Middle East and Europe.

There are no generally accepted relations between Afroasiatic and any other language family. However, several proposals grouping Afroasiatic with one or more other language families have been made. The best-known of these are the following:

- Hermann Möller (1906) argued for a relation between Semitic and the Indo-European languages. This proposal was accepted by a few linguists (e.g. Holger Pedersen and Louis Hjelmslev). (For a fuller account, see Indo-Semitic languages.) However, the theory has little currency today, although most linguists do not deny the existence of grammatical similarities between both families (such as grammatical gender, noun-adjective agreement, three-way number distinction, and vowel alternation as a means of derivation).

- Apparently influenced by Möller (a colleague of his at the University of Copenhagen), Holger Pedersen included Hamito-Semitic (the term replaced by Afroasiatic) in his proposed Nostratic macro-family (cf. Pedersen 1931:336–338), also included the Indo-European, Uralic, Altaic, Yukaghir languages, and Dravidian Languages. This inclusion was retained by subsequent Nostraticists, starting with Vladislav Illich-Svitych and Aharon Dolgopolsky.

- Joseph Greenberg (2000–2002) did not reject a relationship of Afroasiatic to these other languages, but he considered it more distantly related to them than they were to each other, grouping instead these other languages in a separate macro-family, which he called Eurasiatic, and to which he added Chukotian, Gilyak, Korean, Japanese-Ryukyuan, Eskimo–Aleut, and Ainu.

- Most recently, Sergei Starostin's school has accepted Eurasiatic as a subgroup of Nostratic, with Afroasiatic, Dravidian and Kartvelian in Nostratic outside of Eurasiatic. The even larger Borean super-family contains Nostratic as well as Dené-Caucasian and Austric.

Date of Afroasiatic

The earliest written evidence of an Afroasiatic language is an Ancient Egyptian inscription dated to c. 3400 BC (5,400 years ago).[23] Symbols on Gerzean (Naqada II) pottery resembling Egyptian hieroglyphs date back to c. 4000 BC, suggesting an earlier possible dating. This gives us a minimum date for the age of Afroasiatic. However, Ancient Egyptian is highly divergent from Proto-Afroasiatic (Trombetti 1905: 1–2), and considerable time must have elapsed in between them. Estimates of the date at which the Proto-Afroasiatic language was spoken vary widely. They fall within a range between approximately 7,500 BC (9,500 years ago), and approximately 16,000 BC (18,000 years ago). According to Igor M. Diakonoff (1988: 33n), Proto-Afroasiatic was spoken c. 10,000 BC. Christopher Ehret (2002: 35–36) asserts that Proto-Afroasiatic was spoken c. 11,000 BC at the latest, and possibly as early as c. 16,000 BC. These dates are older than those associated with other proto-languages.

Afroasiatic Urheimat

The term Afroasiatic Urheimat (Urheimat meaning "original homeland" in German) refers to the hypothetical place where Proto-Afroasiatic language speakers lived in a single linguistic community, or complex of communities, before this original language dispersed geographically and divided into distinct languages. Afroasiatic languages are today primarily spoken in West Asia, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and parts of the Sahel. Their distribution seems to have been influenced by the Sahara pump operating over the last 10,000 years.

There is no agreement when or where the original homeland of this language family existed. Proposed locations include North Africa, the Horn of Africa, the Eastern Sahara,[24][25][26][27][28] and the Levant.[29][30]

Similarities in grammar and syntax

| ↓ Number | Language → | Arabic | Coptic | Kabyle | Somali | Beja | Hausa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verb → | katab | mou | afeg | ||||

| Meaning → | write | die | fly | come | eat | drink | |

| singular | 1 | ʼaktubu | timou | ttafgeɣ | imaadaa | tamáni | ina shan |

| 2f | taktubīna | temou | tettafgeḍ | timaadaa | tamtínii | kina shan | |

| 2m | taktubu | kmou | tamtíniya | kana shan | |||

| 3f | smou | tettafeg | tamtíni | tana shan | |||

| 3m | yaktubu | fmou | yettafeg | yimaadaa | tamíni | yana shan | |

| dual | 2 | taktubāni | |||||

| 3f | |||||||

| 3m | yaktubāni | ||||||

| plural | 1 | naktubu | tənmou | nettafeg | nimaadnaa | támnay | muna shan |

| 2m | taktubūna | tetənmou | tettafgem | timaadaan | támteena | kuna shan | |

| 2f | taktubna | tettafgemt | |||||

| 3m | yaktubūna | semou | ttafgen | yimaadaan | támeen | suna shan | |

| 3f | yaktubna | ttafgent | |||||

Widespread (though not universal) features of the Afroasiatic languages include:

- A set of emphatic consonants, variously realized as glottalized, pharyngealized, or implosive.

- VSO typology with SVO tendencies.

- A two-gender system in the singular, with the feminine marked by the sound /t/.

- All Afroasiatic subfamilies show evidence of a causative affix s.

- Semitic, Berber, Cushitic (including Beja), and Chadic support possessive suffixes.

- Morphology in which words inflect by changes within the root (vowel changes or gemination) as well as with prefixes and suffixes.

One of the most remarkable shared features among the Afroasiatic languages is the prefixing verb conjugation (see the table at the start of this section), with a distinctive pattern of prefixes beginning with /ʔ t n y/, and in particular a pattern whereby third-singular masculine /y-/ is opposed to third-singular feminine and second-singular /t-/.

According to Ehret (1996), tonal languages appear in the Omotic and Chadic branches of Afroasiatic, as well as in certain Cushitic languages. The Semitic, Berber and Egyptian branches generally do not use tones phonemically.

Shared vocabulary

The following are some examples of Afroasiatic cognates, including ten pronouns, three nouns, and three verbs.

- Source: Christopher Ehret, Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

- Note: Ehret does not make use of Berber in his etymologies, stating (1995: 12): "the kind of extensive reconstruction of proto-Berber lexicon that might help in sorting through alternative possible etymologies is not yet available." The Berber cognates here are taken from previous version of table in this article and need to be completed and referenced.

- Abbreviations: NOm = 'North Omotic', SOm = 'South Omotic'. MSA = 'Modern South Arabian', PSC = 'Proto-Southern Cushitic', PSom-II = 'Proto-Somali, stage 2'. masc. = 'masculine', fem. = 'feminine', sing. = 'singular', pl. = 'plural'. 1s. = 'first person singular', 2s. = 'second person singular'.

- Symbols: Following Ehret (1995: 70), a caron ˇ over a vowel indicates rising tone, and a circumflex ^ over a vowel indicates falling tone. V indicates a vowel of unknown quality. Ɂ indicates a glottal stop. * indicates reconstructed forms based on comparison of related languages.

| Proto-Afroasiatic | Omotic | Cushitic | Chadic | Egyptian | Semitic | Berber |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Ɂân- / *Ɂîn- or *ân- / *în- ‘I’ (independent pronoun) | *in- ‘I’ (Maji (NOm)) | *Ɂâni ‘I’ | *nV ‘I’ | ink 'I' | *Ɂn ‘I’ | nek / nec "I, me" |

| *i or *yi ‘me, my’ (bound) | i ‘I, me, my’ (Ari (SOm)) | *i or *yi ‘my’ | *i ‘me, my’ (bound) | -i (1s. suffix) | *-i ‘me, my’ | inu / nnu / iw "my" |

| *Ɂǎnn- / *Ɂǐnn- or *ǎnn- / *ǐnn- ‘we’ | *nona / *nuna / *nina (NOm) | *Ɂǎnn- / *Ɂǐnn- ‘we’ | — | inn ‘we’ | *Ɂnn ‘we’ | nekni / necnin / neccin "we" |

| *Ɂânt- / *Ɂînt- or *ânt- / *înt- ‘you’ (sing.) | *int- ‘you’ (sing.) | *Ɂânt- ‘you’ (sing.) | — | ntt IInd pers fem | *Ɂnt ‘you’ (sing.) | netta "he" (keyy / cek "you" (masc. sing.)) |

| *ku, *ka ‘you’ (masc. sing., bound) | — | *ku ‘your’ (masc. sing.) (PSC) | *ka, *ku (masc. sing.) | -k (2s. masc. suffix) | -ka (2s. masc. suffix) (Arabic) | inek / nnek / -k "your" (masc. sing.) |

| *ki ‘you’ (fem. sing., bound) | — | *ki ‘your’ (fem. sing.) | *ki ‘you’ (fem. sing.) | -ṯ (fem. sing. suffix, < *ki) | -ki (2s. fem. sing. suffix) (Arabic) | -m / nnem / inem "your" (fem. sing.) |

| *kūna ‘you’ (plural, bound) | — | *kuna ‘your’ (pl.) (PSC) | *kun ‘you’ (pl.) | -ṯn ‘you’ (pl.) | *-kn ‘you, your’ (fem. pl.) | -kent, kennint "you" (fem. pl.) |

| *si, *isi ‘he, she, it’ | *is- ‘he’ | *Ɂusu ‘he’, *Ɂisi ‘she’ | *sV ‘he’ | sw ‘he, him’, sy ‘she, her’ | *-šɁ ‘he’, *-sɁ ‘she’ (MSA) | -s / nnes / ines "his/her/its" |

| *ma, *mi ‘what?’ | *ma- ‘what?’ (NOm) | *ma, *mi (interr. root) | *mi, *ma ‘what?’ | m ‘what?’, ‘who?’ | mā (Arabic, Hebrew) / mu? (Assyrian) ‘what?’ | ma? / mayen? / min? "what?" |

| *wa, *wi ‘what?’ | *w- ‘what?’ | *wä / *wɨ ‘what?’ (Agaw) | *wa ‘who?’ | wy ‘how ...!’ | mamek? / mamec? / amek? "how? | |

| *dîm- / *dâm- ‘blood’ | *dam- ‘blood’ (Gonga) | *dîm- / *dâm- ‘red’ | *d-m- ‘blood’ (West Chadic) | i-dm-i ‘red linen’ | *dm / dǝma (Assyrian) / dom (Hebrew) ‘blood’ | idammen "bloods" |

| *îts ‘brother’ | *itsim- ‘brother’ | *itsan or *isan ‘brother’ | *sin ‘brother’ | sn ‘brother’ | ax (Hebrew) "brother" | uma / gʷma "brother" |

| *sǔm / *sǐm- ‘name’ | *sum(ts)- ‘name’ (NOm) | *sǔm / *sǐm- ‘name’ | *ṣǝm ‘name’ | smi ‘to report, announce’ | *ism (Arabic) / shǝma (Assyrian) ‘name’ | isen / isem "name" |

| *-lisʼ- ‘to lick’ | litsʼ- ‘to lick’ (Dime (SOm)) | — | *alǝsi ‘tongue’ | ns ‘tongue’ | *lsn ‘tongue’ | iles "tongue" |

| *-maaw- ‘to die’ | — | *-umaaw- / *-am-w(t)- ‘to die’ (PSom-II) | *mǝtǝ ‘to die’ | mwt ‘to die’ | *mwt / mawta (Assyrian) ‘to die’ | mmet "to die" |

| *-bǐn- ‘to build, to create; house’ | bin- ‘to build, create’ (Dime (SOm)) | *mǐn- / *mǎn- ‘house’; man- ‘to create’ (Beja) | *bn ‘to build’; *bǝn- ‘house’ | — | *bnn / bani (Assyrian) / bana (Hebrew) ‘to build’ | *bn(?) (esk "to build") |

There are two etymological dictionaries of Afroasiatic, one by Christopher Ehret, and one by Vladimir Orel and Olga Stolbova. The two dictionaries disagree on almost everything. The following table contains the thirty roots or so (out of thousands) that represent a fragile consensus of present research:

| Number | Proto-Afroasiatic Form | Meaning | Berber | Chadic | Cushitic | Egyptian | Omotic | Semitic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | *ʔab | father | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 2 | (ʔa-)bVr | bull | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 3 | (ʔa-)dVm | red, blood | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 4 | *(ʔa-)dVm | land, field, soil | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| 5 | ʔa-pay- | mouth | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 6 | ʔigar/ *ḳʷar- | house, enclosure | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 7 | *ʔil- | eye | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 8 | (ʔi-)sim- | name | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 9 | *ʕayn- | eye | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| 10 | *baʔ- | go | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 11 | *bar- | son | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 12 | *gamm- | mane, beard | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 13 | *gVn | cheek, chin | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| 14 | *gʷarʕ- | throat | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 15 | *gʷinaʕ- | hand | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| 16 | *kVn- | co-wife | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 17 | *kʷaly | kidney | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 18 | *ḳa(wa)l-/ *qʷar- | to say, call | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| 19 | *ḳas- | bone | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 20 | *libb | heart | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 21 | *lis- | tongue | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 22 | *maʔ- | water | *aman | *aman | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 23 | *mawVt- | to die | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 24 | *sin- | tooth | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 25 | *siwan- | know | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| 26 | *inn- | I, we | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 27 | *-k- | thou | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 28 | *zwr | seed | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| 29 | *ŝVr | root | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| 30 | *šun | to sleep, dream | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

Etymological bibliography

Some of the main sources for Afroasiatic etymologies include:

- Cohen, Marcel. 1947. Essai comparatif sur le vocabulaire et la phonétique du chamito-sémitique. Paris: Champion.

- Diakonoff, Igor M. et al. 1993–1997. "Historical-comparative vocabulary of Afrasian", St. Petersburg Journal of African Studies 2–6.

- Ehret, Christopher. 1995. Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian): Vowels, Tone, Consonants, and Vocabulary (= University of California Publications in Linguistics 126). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Orel, Vladimir E. and Olga V. Stolbova. 1995. Hamito-Semitic Etymological Dictionary: Materials for a Reconstruction. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10051-2.

See also

- Borean languages

- Indo-European languages

- Indo-Semitic languages

- Languages of Africa

- Languages of Asia

- Languages of Europe

- Nostratic languages

- Proto-Afroasiatic language

References

- 1 2 3 Sands, Bonny (2009). "Africa’s Linguistic Diversity". Language and Linguistics Compass 3/2 (2009): 559–580, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00124.x

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Afro-Asiatic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Daniel Don Nanjira, African Foreign Policy and Diplomacy: From Antiquity to the 21st Century, (ABC-CLIO: 2010).

- ↑ Ethnologue family tree for Afroasiatic languages

- ↑ Summary by language family

- ↑ https://www.ethnologue.com/language/ara

- ↑ Ethnologue - Hausa

- ↑ Dekel, Nurit (2014). Colloquial Israeli Hebrew: A Corpus-based Survey. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-037725-5.

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Northeastern Neo-Aramaic". Glottolog 2.2. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Beyer, Klaus; John F. Healey (trans.) (1986). The Aramaic Language: its distribution and subdivisions. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. p. 44. ISBN 3-525-53573-2.

- 1 2 3 Merritt, Ruhlen (1991). A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification. Stanford University Press. pp. 76 & 87. ISBN 0804718946.

- ↑ Gregersen, Edgar A. (1977). Language in Africa: An Introductory Survey. Taylor & Francis. p. 116. ISBN 0677043805. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- 1 2 Lipiński, Edward (2001). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar. Peeters Publishers. pp. 21–22. ISBN 90-429-0815-7.

- ↑ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 8; Volume 22. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1998. p. 722. ISBN 0-85229-633-9.

- ↑ Harrassowitz Verlag - The Harrassowitz Publishing House

- 1 2 Merritt Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification, Stanford University Press, 1991, pp. 80–1

- ↑ Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African History, CRC Press, 2005, p.797

- ↑ Merritt Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages, (Stanford University Press: 1991), p.109

- ↑ Sands, Bonny E. (1998) 'Eastern and Southern African Khoisan: evaluating claims of distant linguistic relationships.' Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 14. Köln: Köppe.

- 1 2 Ruhlen, p.117

- ↑ Everett Welmers, William (1974). African Language Structures. University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 0520022106.

- ↑ Is Omotic Afroasiatic? (In Norwegian)

- ↑ Earliest Egyptian Glyphs

- ↑ Blench R (2006) Archaeology, Language, and the African Past, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0-7591-0466-2, ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=esFy3Po57A8C

- ↑ Ehret C, Keita SOY, Newman P (2004) The Origins of Afroasiatic a response to Diamond and Bellwood (2003) in the Letters of SCIENCE 306, no. 5702, p. 1680 doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c

- ↑ Bernal M (1987) Black Athena: the Afroasiatic roots of classical civilization, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-3655-3, ISBN 978-0-8135-3655-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=yFLm_M_OdK4C

- ↑ Bender ML (1997), Upside Down Afrasian, Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 50, pp. 19-34

- ↑ Militarev A (2005) Once more about glottochronology and comparative method: the Omotic-Afrasian case, Аспекты компаративистики - 1 (Aspects of comparative linguistics - 1). FS S. Starostin. Orientalia et Classica II (Moscow), p. 339-408.

- ↑ Quantitative Approaches to Linguistic Diversity: Commemorating the Centenary of the Birth of Morris Swadesh. p. 73.

- ↑ John A. Hall, I. C. Jarvie (2005). Transition to Modernity: Essays on Power, Wealth and Belief. p. 27.

Bibliography

- Anthony, David. 2007. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Barnett, William and John Hoopes (editors). 1995. The Emergence of Pottery. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-517-8

- Bender, Lionel et al. 2003. Selected Comparative-Historical Afro-Asiatic Studies in Memory of Igor M. Diakonoff. LINCOM.

- Bomhard, Alan R. 1996. Indo-European and the Nostratic Hypothesis. Signum.

- Diakonoff, Igor M. 1988. Afrasian Languages. Moscow: Nauka.

- Diakonoff, Igor M. 1996. "Some reflections on the Afrasian linguistic macrofamily." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 55, 293.

- Diakonoff, Igor M. 1998. "The earliest Semitic society: Linguistic data." Journal of Semitic Studies 43, 209.

- Dimmendaal, Gerrit, and Erhard Voeltz. 2007. "Africa". In Christopher Moseley, ed., Encyclopedia of the world's endangered languages.

- Ehret, Christopher. 1995. Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian): Vowels, Tone, Consonants, and Vocabulary. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Ehret, Christopher. 1997. Abstract of "The lessons of deep-time historical-comparative reconstruction in Afroasiatic: reflections on Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic: Vowels, Tone, Consonants, and Vocabulary (U.C. Press, 1995)", paper delivered at the Twenty-fifth Annual Meeting of the North American Conference on Afro-Asiatic Linguistics, held in Miami, Florida on 21–23 March 1997.

- Finnegan, Ruth H. 1970. "Afro-Asiatic languages West Africa". Oral Literature in Africa, pg 558.

- Fleming, Harold C. 2006. Ongota: A Decisive Language in African Prehistory. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1950. "Studies in African linguistic classification: IV. Hamito-Semitic." Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 6, 47-63.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1955. Studies in African Linguistic Classification. New Haven: Compass Publishing Company. (Photo-offset reprint of the SJA articles with minor corrections.)

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1963. The Languages of Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University. (Heavily revised version of Greenberg 1955.)

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1966. The Languages of Africa (2nd ed. with additions and corrections). Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1981. "African linguistic classification." General History of Africa, Volume 1: Methodology and African Prehistory, edited by Joseph Ki-Zerbo, 292–308. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 2000–2002. Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family, Volume 1: Grammar, Volume 2: Lexicon. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Hayward, R. J. 1995. "The challenge of Omotic: an inaugural lecture delivered on 17 February 1994". London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- Heine, Bernd and Derek Nurse. 2000. African Languages, Chapter 4. Cambridge University Press.

- Hodge, Carleton T. (editor). 1971. Afroasiatic: A Survey. The Hague – Paris: Mouton.

- Hodge, Carleton T. 1991. "Indo-European and Afro-Asiatic." In Sydney M. Lamb and E. Douglas Mitchell (editors), Sprung from Some Common Source: Investigations into the Prehistory of Languages, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 141–165.

- Huehnergard, John. 2004. "Afro-Asiatic." In R.D. Woodard (editor), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages, Cambridge – New York, 2004, 138–159.

- Militarev, Alexander. "Towards the genetic affiliation of Ongota, a nearly-extinct language of Ethiopia," 60 pp. In Orientalia et Classica: Papers of the Institute of Oriental and Classical Studies, Issue 5. Мoscow. (Forthcoming.)

- Newman, Paul. 1980. The Classification of Chadic within Afroasiatic. Leiden: Universitaire Pers Leiden.

- Ruhlen, Merritt. 1991. A Guide to the World's Languages. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Sands, Bonny. 2009. "Africa’s linguistic diversity". In Language and Linguistics Compass 3.2, 559–580.

- Theil, R. 2006. Is Omotic Afro-Asiatic? Proceedings from the David Dwyer retirement symposium, Michigan State University, East Lansing, 21 October 2006.

- Trombetti, Alfredo. 1905. L'Unità d'origine del linguaggio. Bologna: Luigi Beltrami.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad 2003. Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew, Palgrave Macmillan.

External links

- Afro-Asiatic at the Linguist List MultiTree Project (not functional as of 2014): Genealogical trees attributed to Delafosse 1914, Greenberg 1950–1955, Greenberg 1963, Fleming 1976, Hodge 1976, Orel & Stolbova 1995, Diakonoff 1996–1998, Ehret 1995–2000, Hayward 2000, Militarev 2005, Blench 2006, and Fleming 2006

- Afro-Asiatic and Semitic genealogical trees, presented by Alexander Militarev at his talk "Genealogical classification of Afro-Asiatic languages according to the latest data" at the conference on the 70th anniversary of V.M. Illich-Svitych, Moscow, 2004; short annotations of the talks given there (in Russian)

- The prehistory of a dispersal: the Proto-Afrasian (Afroasiatic) farming lexicon, by Alexander Militarev in "Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis", eds. P. Bellwood & C. Renfrew. (McDonald Institute Monographs.) Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2002, p. 135-50.

- Once More About Glottochronology And The Comparative Method: The Omotic-Afrasian case, by Alexander Militarev in "Aspects of Comparative Linguistics", v. 1. Moscow: RSUH Publishers, 2005, pp. 339–408.

- Root Extension And Root Formation In Semitic And Afrasian, by Alexander Militarev in "Proceedings of the Barcelona Symposium on comparative Semitic", 19-20/11/2004. Aula Orientalis 23/1-2, 2005, pp. 83–129.

- Akkadian-Egyptian lexical matches, by Alexander Militarev in "Papers on Semitic and Afroasiatic Linguistics in Honor of Gene B. Gragg." Ed. by Cynthia L. Miller. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 60. Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 2007, p. 139-145.

- A comparison of Orel-Stolbova's and Ehret's Afro-Asiatic reconstructions

- "Is Omotic Afro-Asiatic?" by Rolf Theil (2006)

- NACAL The North American Conference on Afroasiatic Linguistics, now in its 35th year

- Afro-Asiatic webpage of Roger Blench (with family tree).