Afro-Germans

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (500,000 [1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Berlin, Hamburg, Frankfurt, Munich, Cologne | |

| Languages | |

| German, various African languages | |

| Religion | |

| Islam, Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism, Atheism |

Afro-Germans (German: Afrodeutsche)[2] or Black Germans (German: schwarze Deutsche) are an ethnic group which exists in certain parts of the Federal Republic of Germany such as Hamburg, Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich, and Cologne and in a variety of smaller settlements across Germany. Afro-Germans are as well indistinguishably defined as German citizens of Black African descent.

Cities such as Hamburg and Berlin, centers of occupation forces following World War II and more recent immigration, have substantial Afro-German communities, with a relatively high percentage of ethnically mixed and multiracial families. With modern trade and migration, communities such as Frankfurt, Munich, and Cologne have an increasing number of Afro-Germans. As of 2005, there were approximately 800,000 Afro-Germans in a nation of 80 million persons. This number is difficult to estimate because the German census does not use race as a category, following the genocide committed during World War II under the "German racial ideology".[3] Up to 70,000 (2% of the population) people of Afro-German origin live in Berlin.[4]

History

African and German interaction 1600 to late 1800s

The first Africans in Germany were brought as household servants around the 17th century.[5] During the 1720s, Ghana-born Anton Wilhelm Amo was sponsored by a German duke to become the first African to attend a European university; after completing his studies, he taught and wrote in philosophy. Later, Africans were brought as slaves from the western coast of Africa where a number of German estates were established, primarily on the Gold Coast. After King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia sold his Ghana Groß Friedrichsburg estates in Africa in 1717, from which up to 30,000 people had been sold to the Dutch East India Company, the new owners were bound by contract to "send 12 negro boys, six of them decorated with golden chains," to the king. The enslaved children were brought to Potsdam and Berlin.[6]

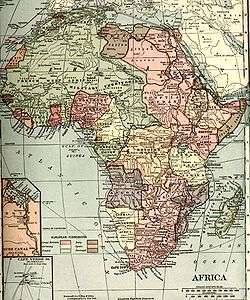

Africans and German interaction between 1884 and 1945

At the 1884 Berlin Congo conference, attended by all major powers of the day, European states divided Africa into areas of influence which they would control. Germany controlled colonies in the African Great Lakes region and West Africa, from which numerous Africans migrated to Germany for the first time. Germany appointed indigenous specialists for the colonial administration and economy, and many young Africans went to Germany to be educated. Some received higher education at German schools and universities, but the majority were trained at mission training and colonial training centers as officers or domestic mission teachers. Africans frequently served as interpreters for African languages at German-Africa research centers, and with the colonial administration. Others migrated to Germany as former members of the German protection troops, the Askari.

The Afrikanisches Viertel in Berlin is also a legacy of the colonial period, with a number of streets and squares named after countries and locations tied to the German colonial empire. It is now home to a substantial portion of Berlin's residents of African heritage.

Interracial couples in the colonies were subjected to strong pressure in a campaign against miscegenation, which included invalidation of marriages, declaring the mixed-race children illegitimate, and stripping them of German citizenship.[7] During extermination of the Nama people in 1907 by Germany, the German director for colonial affairs, Bernhard Dernburg, stated that "some native tribes, just like some animals, must be destroyed".[8]

Weimar Republic

In the course of World War I, the Belgians, British and French took control of Germany's colonies in Africa. The situation for the African colonials in Germany changed in various ways. For example, Africans who possessed a colonial German identification card had a status entitling them to treatment as "members of the former protectorates". After the Treaty of Versailles (1919), the Africans were encouraged to become citizens of their respective mandate countries, but most preferred to stay where they were. In numerous petitions (well documented for German Togoland by P. Sebald and for Cameroon by A. Rüger), they tried to inform the German public about the conditions in the colonies, and continued to request German help and support.

Africans founded the bilingual periodical that was published in German and Duala: Elolombe ya Cameroon (Sun of Cameroon). A political group of Africans established the German branch of a Paris-based human-rights organization: "the German section of the League to the Defense of the Negro Race".

Many of the Afro-Germans endured the Great Depression in Germany without being able to gain unemployment compensation, as this depended on German citizenship. Some Afro-Germans were supported through a small budget from the German Foreign Office.

Nazi Germany

The conditions for Afro-Germans in Germany grew worse during the Nazi period. Naturalized Afro-Germans lost their passports. Working conditions and travel were made extremely difficult for Afro-German musicians, variety, circus or film professionals. Based on racist propaganda, employers were unable to retain or hire Afro-German employees.

The Nazis speculated about gaining the support of Afro-Germans from former German colonies for pro-German colonial propaganda. They planned an "African colonial empire under German predominance". The legislation for a planned, apartheid-like system already existed in design in 1940, including laws for slaves and an Afro-German passport design. Nazi Germany never approached the realization of its colonial dreams.

Afro-Germans in Germany were socially isolated and forbidden to have sexual relations and marriages with Aryans by the racial laws.[9][10] In continued discrimination directed at the so-called Rhineland bastards, Nazi officials subjected some 500 Afro-German children in the Rhineland to forced sterilization.[11] Blacks were considered "enemies of the race-based state" along with Jews and Gypsies.[12] The Nazis originally sought to rid the German state of Jews and Romani by means of deportation (and later extermination), while Afro-Germans were to be segregated and eventually exterminated through compulsory sterilization.[12]

For an autobiography of an Afro-German in Germany under Nazi rule see Hans Massaquoi's book Destined to Witness.

Since 1945

The end of World War II brought Allied occupation forces into Germany. United States, British and French forces included numerous soldiers of African American, Afro-Caribbean or African descent, and some of them fathered children with ethnic German women. At the time, the armed forces generally had non-fraternization rules and discouraged interracial marriages. Most single ethnic German mothers kept their "brown babies", but thousands were adopted by American families and grew up in the United States. Often they did not learn their full ancestry until reaching adulthood.

Until the end of the Cold War, the United States kept more than 100,000 U.S. soldiers stationed on German soil. These men established their lives in Germany. They often brought families with them or founded new ones with ethnic German wives and children. The federal government of West Germany pursued a policy of isolating or removing from Germany those children that it described as "mixed-race negro children".[13]

Audre Lorde, Black American writer and activist, spent from 1984-1992 teaching at the Free University of Berlin. In her time in Germany, often called "The Berlin Years," she helped push the coining of the term "Afro-German" into a powerful movement that addressed the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexual orientation. She encouraged Black German women like May Ayim and Ika Hügel-Marshall to write and publish poems and autobiographies as a means of gaining visibility and writing themselves into existence. She wanted intersectional global feminism and acted as a fiery spark for that movement in Germany.

Cities with considerable populations of Afro-German descent include the following:[14][15][16]

| City | Number |

|---|---|

| Berlin | 70,000 (2%) |

| Hamburg | 54,000 (3%) |

| Frankfurt | 14,000 (2%) |

| Munich | 14,000 (1%) |

| Dortmund | 12,000 (2%) |

| Cologne | 11,000 (1%) |

| Bremen | 9,000 (1.5%) |

| Stuttgart | 8,000 (1.3%) |

Immigration

Since 1981, Germany has had immigration from African states, mostly from Nigeria and Ghana, who were seeking work. Some of the Ghanaians also came to study in German universities.

Below are the largest (Sub-sahara) African groups in Germany.

| Country of Birth | Immigrants in Germany (2015 Census) |

|---|---|

| 37,404 | |

| 33.900 | |

| 31,100 | |

| 29,590 | |

| 19,800 | |

| 14,510 | |

| 12,090 | |

| 10,608 | |

| 10,395 | |

| 10,071 | |

| 8,891 | |

| |

6,608 |

| 6,362 | |

| |

5,611 |

| |

5,599 |

| |

5,400 |

| |

5,308 |

| |

4,888 |

| |

3,688 |

| |

2,818 |

| |

2,480 |

| |

2,119 |

| |

2,111 |

| |

1,213 |

Afro-Germans in literature

- Edugyan, Esi (2011). Half Blood Blues. Serpent's Tail. p. 343. Novel about a multiracial jazz group in Nazi Germany. The band's young trumpeter is a Rhineland Bastard who eventually is taken by the Nazis, while other members of the band are African Americans.

- Jones, Gayl (1998). The Healing. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-6314-9. Novel about a faith healer and rock band manager, featuring an Afro-German character, Josef Ehelich von Fremd, an affluent fellow who works in arbitrage and owns fine racehorses.

- Massaquoi, Hans J. (1999). Destined to Witness: Growing Up Black in Nazi Germany. W. Morrow. ISBN 978-0060959616. An autobiography by Hans J. Massaquoi, born in Hamburg, Germany, to a white German mother and Liberian Vai father, the grandson of Momulu Massaquoi.

Notable Afro-Germans in modern Germany

Politics and social life

- Karamba Diaby, Afro German politician. Member of the Bundestag.

- John Ehret, Germany's first Afro German mayor.

- Charles M. Huber, Afro German politician. Member of the Bundestag.

- Ika Hügel-Marshall, wrote about growing up in postwar Germany

- Hans Massaquoi, journalist, wrote about his childhood in Nazi Germany.

- Zeca Schall, Afro German politician.

- Sylvie Nantcha, Afro-German politician

Art, culture, and music

The cultural life of Afro-Germans has great variety and complexity. With the emergence of MTV and Viva, the popularity of American pop culture promoted Afro-German representation in German media and culture.

May Opitz, who wrote under the pen name May Ayim, was an Afro-German poet, educator, and activist. She was a co-editor of the book Farbe bekennen, whose English translation was published as Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out.

Afro-German musicians include:

- Adé Bantu

- Afrob

- Ayọ

- B-Tight

- Cassandra Steen

- J. Cole

- Denyo

- Deso Dogg

- D-Flame

- Francisca Urio

- Haddaway

- Harris

- Jessica Wahls

- Jonesmann

- Joy Denalane

- U-Jean

- KeyLiza

- Lou Bega

- Mamadee

- Mark Medlock

- Meshell Ndegeocello

- Nana (rapper)

- Nneka

- Patrice Bart-Williams

- Raptile

- Roberto Blanco

- Rob Pilatus

- Samy Deluxe

- SchoolBoy Q

- Taktloss

Film

The SFD - Schwarze Filmschaffende in Deutschland (Black Artists in German Film, literally Black Filmmakers in Germany) is a professional association based in Berlin for directors, producers, screenwriters, and actors who are Afro-Germans or of Black African origin and living in Germany. They have organized the "New Perspectives" series at the Berlinale film festival.[2]

Afro-Germans in film include:

- Louis Brody

- Nisma Cherrat (actress)

- Carol Campbell (actress)

- Elfie Fiegert

- Günther Kaufmann

- Araba Walton

Sport

- Richard Adjei, member of the German bobsleigh team

- Dennis Aogo, footballer

- Stephen Arigbabu, basketball player

- Gerald Asamoah, footballer

- Karim Bellarabi, footballer

- Collin Benjamin, footballer

- Jérôme Boateng, footballer

- Kevin Prince Boateng, footballer

- John Brooks, footballer

- Sidney Sam, footballer

- Francis Bugri, footballer

- Cacau, footballer

- Timothy Chandler, footballer

- Marvin Compper, footballer

- Bakary Diakite, footballer

- Chinedu Ede, footballer

- Kasim Edebali American Football player (New Orleans Saints)

- Florence Ekpo-Umoh, athlete

- Matthias Fahrig, athlete

- Kamghe Gaba, athlete

- Robert Garrett, basketball player

- Serge Gnabry, footballer

- Julian Green, footballer

- Demond Greene, basketball player

- Leon Guwara, footballer

- Misan Haldin, basketball player

- Elias Harris, basketball player

- Jimmy Hartwig, footballer

- Benjamin Henrichs, footballer

- Raphael Holzdeppe, pole vaulter

- Fabian Johnson, footballer

- Jermaine Jones, footballer

- Steffi Jones, footballer

- Gideon Jung, footballer

- Thilo Kehrer, footballer

- Alex King, basketball player

- Linda Kisabaka, athlete

- Erwin Kostedde, footballer

- Mohammed Lartey, footballer

- Andrej Mangold, basketball player

- Ousman Manneh, footballer

- David McCray, basketball player

- Amewu Mensah, athlete

- Jean-Claude Mpassy, footballer

- Sabrina Mulrain, athlete

- David Odonkor, footballer

- Akwasi Oduro, footballer

- Ademola Okulaja, basketball player

- Navina Omilade, footballer

- Patrick Owomoyela, footballer

- Kofi Amoah Prah, athlete

- Antonio Rüdiger, footballer

- Leroy Sané, footballer

- Célia Šašić, footballer

- Dennis Schröder, basketball player

- Leyti Seck, alpine skier

- Davie Selke, footballer

- Lennard Sowah, footballer

- Richard Sukuta-Pasu, footballer

- Robin Szolkowy, figure skater

- Jonathan Tah, footballer

- Assimiou Touré, footballer

- Akeem Vargas, basketball player

- Reinhold Yabo, footballer

- Michael Zimmer, footballer

References

- ↑ Smith, David G. (2008-06-05). "German Newspaper Slammed for Racist Cover". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- 1 2 Wolf, Joerg (2007-02-23). "Black History Month in Germany". Atlantic Review. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Mazon, Patricia (2005). Not So Plain as Black and White: Afro-German Culture and History, 1890–2000. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 1-58046-183-2.

- ↑ "Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland". Isdonline.de. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

- ↑ "Black Germans", in Prem Poddar, Rajeev Patke and Lars Jensen, Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures--Continental Europe and Its Colonies, Edinburgh University Press, 2008

- ↑ Prem Poddar, Rajeev Patke and Lars Jensen, Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures--Continental Europe and Its Colonies, Edinburgh University Press, 2008, page 257

- ↑ Not So Plain as Black and White: Afro-German Culture and History, 1890–2000, Patricia M. Mazón, Reinhild Steingröver, page 18

- ↑ Ben Kiernan, Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500–2000, p. 417

- ↑

- ↑ S. H. Milton (2001). Robert Gellately and Nathan Stoltzfus, ed. Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany. Princeton University Press. pp. 216, 231. ISBN 9780691086842.

- ↑ Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. Penguin. pp. 526–8. ISBN 1-59420-074-2.

- 1 2 Simone Gigliotti, Berel Lang. The Holocaust: a reader. Malden, Massachusetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; Carlton, Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. Pp. 14.

- ↑ Women in German Yearbook 2005: Feminist Studies in German Literature & Culture, Marjorie Gelus, Helga W. Kraft page 69

- ↑ Einwohnerregisterstatistik Berlin Archived May 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. (in German). statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de.

- ↑ "Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland". Isdonline.de. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

- ↑ "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund I". Bpb.de (in (in German)). 2015-12-31. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

Further reading

Ayim, May, Katharina Oguntoye, and Dagmar Schultz. Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out (1986). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992.

Campt, Tina. Other Germans Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender, and Memory in the Third Reich. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2004.

El-Tayeb, Fatima. European Others: Queering Ethnicity in Postnational Europe. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Hine, Darlene Clark, Trica Danielle Keaton, and Stephen Small, eds. Black Europe and the African Diaspora. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. Who Is a German?: Historical and Modern Perspectives on Africans in Germany. Ed. Leroy Hopkins. Washington, D.C: American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, the Johns Hopkins University, 1999.

Lemke Muniz de Faria, Yara-Colette. "'Germany's "Brown Babies" Must Be Helped! Will You?': U.S. Adoption Plans for Afro-German Children, 1950–1955." Callaloo 26.2 (2003): 342–362.

Mazón, Patricia M., and Reinhild Steingröver, eds. Not so Plain as Black and White: Afro-German Culture and History, 1890–2000. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2005.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity. Duke University Press, 2005.

External links

- Black German Heritage and Research Association

- Black German Cultural Society Inc

- African Union Diaspora Committee Deutschland Zentralrat der Afrikanischen Diaspora Deutschland mit Mandat der Afrikanischen Union

- May Ayim Award - The 1st Black German International Literature Award

- Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland

- African Diaspora in Germany (in German)

- cyberNomads - The Black German Databank Network and Media Channel Our Knowledge Resource on the Net

- SFD – Schwarze Filmschaffende in Deutschland

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Bibliography

- Pocast in which Fatima El-Tayeb (Director of the Critical Gender Studies programme at the University of California, San Diego) talks about the need to reassess Europe’s internalist narrative and the discourse of integration.