African forest elephant

| African forest elephant[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | Loxodonta |

| Species: | L. cyclotis |

| Binomial name | |

| Loxodonta cyclotis (Matschie, 1900) | |

| |

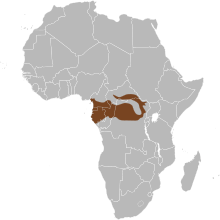

| African forest elephant range | |

The African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) is a forest-dwelling species of elephant found in the Congo Basin. It is the smallest of the three extant species of elephant, but still one of the largest living terrestrial animals. The African forest elephant and the African bush elephant, L. africana, were considered to be one species until genetic studies indicated that they separated an estimated 2–7 million years ago.[3] Due to a slower birth rate, the forest elephant takes longer to recover from poaching, which caused its population to fall by 65% from 2002 to 2014.[4]

Classification

The African forest elephant was once considered to be a subspecies, Loxodonta africana cyclotis, of the African elephant, together with the African bush elephant. DNA tests, however, indicated that the two populations were much more genetically distinct than previously believed.[5] In 2010, a genetic study confirmed they are separate species which diverged from each other an estimated two to seven million years ago.[3][6] Still, many governmental (e.g. USFWS) and non-governmental agencies (e.g. IUCN) consider the forest elephant to be a subspecies for regulatory and conservation purposes. In 2016, DNA sequence analysis showed that L. cyclotis is more closely related to the extinct European straight-tusked elephant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, than it is to L. africana.[7]

The disputed pygmy elephants of the Congo Basin, often assumed to be a separate species (Loxodonta pumilio) by cryptozoologists, are probably forest elephants whose diminutive size or early maturity is due to environmental conditions.[8]

Physical Characteristics

Generally, these forest-dwelling elephants are smaller and darker than their savanna relatives, the bush elephants.[9] The species normally has five toenails on the forefoot and four on the hind foot, like the Asian elephant but unlike the African bush elephant which normally has four toenails on the forefoot and three on the hind foot. They also protect themselves from the sun by using sand.

Size

A male African forest elephant rarely exceeds 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in height, considerably smaller than the bush species which is usually over 3 m (9.8 ft) and sometimes almost 4 m (13.1 ft) tall. L. cyclotis reportedly weighs around 2.7 tonnes (5,950 lb), with the largest specimens attaining 6 tonnes (13,230 lb).[10] Pygmy elephants of the Congo Basin, presumed to be a subgroup of L. cyclotis, have reportedly weighed as little as 900 kg (1,980 lb) as adults.[11]

Skin

Elephants have sensitive skin which can make them prone to sunburns, especially in the young.[12] The wrinkles in the elephants skin help keep them cool by giving heat a larger surface area through which it can dissipate. The creases in the hide of the elephant trap and absorb moisture longer than one with smooth skin; that prolongs the evaporation process, which sanctions the elephant to release up to 75 percent of its body heat. Since these elephants live in areas where temperatures can reach up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the daytime, the forest elephants skin in significantly more wrinkled than Asian elephants. [13]

Tusks

Compared to the bush elephant, the African forest elephant has a longer, more narrow mandible. Its tusks are straighter and point downward, unlike the savanna elephant, that have curved tusks. The are also harder and have a more yellow or brownish color.[14] These strong tusks are used to push through the dense undergrowth of their habitat and bull elephants (mature males) are sometimes known to have exceptionally long tusks that reach almost to the ground.[9][15][16] Their tusks can grow to approximately 1.5 meters long and can weight between 50 and 100 pounds, which is around the same size as a small adult human. Males often use their tusks when fighting with one another and to establish dominance.[17]

Trunk

The top lip and nose are elongated into a trunk that is distinctly more hairy than savanna elephants. The trunk, having highly sensitive tactile perception, serves numerous functions. Elephant trunks are more sensitive than human fingers and are used for signaling, detection, drinking and snorkeling through water, sound production and communication, bathing, defense and offense.[18] Their trunk also has over 100,000 individual muscles in it, making it a very strong and useful appendage.[19]

The trunk of this species end in two opposing processes (or lips), which contrasts that of the Asian elephant, whose trunk concludes in a single process. [20]

Ears

Forest elephants have smaller, more rounded ears than the bush elephant. Their ears serve as a cooling system and by simply flapping them, they can reduce their body temperature by up to 10 degrees Fahrenheit. Air permeates the thin ears of the elephant, thereby cooling blood as it goes through a web of blood vessels inside the ear before going back to the body.[21]

Behaviour

.jpg)

African forest elephants travel in smaller groups than other elephant species. A typical group size consists of 2 to 8 individuals. The average family unit is 3 to 5 individuals, usually made up of female relatives. Most family groups are a mother and several of her offspring, or several groups of females and their offspring that interact with one another, especially at forest clearings. Female offspring are philopatric, male offspring disperse at maturity. Unlike African savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana), African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) do not usually interact with other family groups. Male African forest elephants tend to be solitary and only associate with other elephants during the mating season. Males have a dominance hierarchy based on size.[16][22][23][24]

Communication

Since the Loxodonta cyclotis species is newly recognized, there is little to no concrete literature on communication and perception. For these mammals, hearing and smell are the most important senses they possess due to the fact that they do not have good eyesight. They can recognize and hear vibrations through the ground and can detect food sources with their sense of smell. Elephants are also an Arrhythmic species, meaning they have the ability to see just as well in dim light as they can in the daylight. They are capable of doing so because the retina in their eye adjusts nearly as quick as light does.[25][26]

The elephants feet are sensitive and can detect vibrations through the ground, whether its thunder or elephant calls from up to ten miles away. [27]

Reproduction

Females reach sexual maturity between the age of 8 and 12 years, depending on the population density and nutrition available. On average, they begin breeding at the age of 23 and give birth every five to six years.[4] As a result, the birth rate is lower than the bush species, which starts breeding at age 12 and has a calf every three to four years.[4] That lengthy time period allows mothers to devote all the attention that the calf needs in order to teach it all the complex tasks that come with being an elephant, such as using their trunk to eat, wash, and drink.

Baby elephants weight around 232 pounds at birth. Almost immediately, they can already stand up and move around, allowing the mother to roam around and forage, which is also essential to predation. The baby suckles using its mouth while its trunk is held over its head. Their tusks do not come until around 16 months and calves are not weaned until they are roughly 4 or 5 years old. By this time, their tusks are around 14 centimeters long and begin to get in the way of sucking.[24]

Forest elephants have a lifespan of about 60 to 70 years and mature slowly, coming to puberty in their early teens.[24] Males generally pass puberty within the next year or two of females. Between the ages of 15 and 25, males experience "musth," which is a hormonal state they experience marked by increased aggression. The male secretes fluid from the temporal gland between its ear and eye during this time. Younger males often experience musth for a shorter period of time while older males do for a longer time period. When undergoing musth, males have a more erect walk with their head high and tusks inward, they may rub their heads on trees or bushes in order to spread the musth scent, and they may even flap their ears, accompanied by a musth rumble, so the their smell can be blown towards other elephants. The last behavior affiliated with musth is urination. Males allow their urine to slowly come out and spray the insides of their hind legs. All of these behaviors are to advertise to receptive females and competing males their in the musth state.[28]

The females are polyestrous, which means that they are capable of conceiving multiple times a year, which is a reason as to why they do not appear to have a breeding season. However, there does appear to be a peak in conceptions during the two rainy seasons of the year. Generally, the female conceives after two or three matings. Although the female has plenty of room in her uterus to gestate twins, it is rare for twins to be conceived. The female African forest elephant has a pregnancy that lasts 22 months. Based on the maturity, fertility and gestation rates, the African forest elephants have the capabilities of increasing the species' population size by 5% annually in ideal conditions.[29][30]

Diet and ecological role

The African forest elephant is an herbivore, and commonly eats leaves, fruit, and bark, with occasional visits to mineral licks. It eats a high proportion of fruit, and is sometimes the only disperser of some tree species, such as Balanites wilsoniana and Omphalocarpum spp. Elephants have been referred to as "forest gardeners" due to their significant role in seed dispersal and maintaining plant diversity.[31][32] In Afrotropical forests, many of these plant species are disseminated by forest elephants, sometimes at very long dispersal distances, a mutualism that matters to the population dynamics of plants and to the structure of forest tree communities. Moreover, the rate of seed germination of many forest plant species increases significantly after passage through an elephant’s gut.[33]

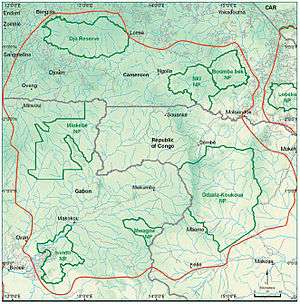

Analysis of 855 elephant dung piles suggested that forest elephants disperse more intact seeds than any other species or genus of large vertebrate in African forests, while GPS telemetry data showed that forest elephants regularly disperse seeds over unprecedented distances compared to other dispersers.[34] The African forest elephant was observed opportunistically over a period of seven years between 1984 and 1991 in lowland rain forest in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon. Diet of elephants at Lopé was diverse, including a minimum of 307 items. The bulk of the diet, in terms of number of species and quantities eaten, came from leaves and bark (70% of all items recorded). Trees represented 73% of the species fed upon. In contrast to savanna-living populations, fruit was an important part of the diet. Fruit of at least 72 species is eaten and the remains of at least one species of fruit was found in 82% of 311 fresh dung piles searched over a one-year period.[35]

A unique aspect of the forest elephants ecology is the appeal they have to clearings in the forest, known as "bais" by Central Africans, where they seek minerals and social interactions.[24]

Threats and conservation

Being the largest land mammal, elephants do not have many natural predators, it is in fact humans, that have proved to be one of the greatest threats to African forest elephants. While there was a ban on the international trade in elephant products including ivory that was implemented in 1990, when the African elephant was added to Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species,[36] the ivory trade continues to be the reason for countless elephant deaths. Another threat to this species is the prolific logging industry in the Central Africa.[15] While selective logging, the more popular practice of extracting wood in Central Africa, may actually benefit forest elephants by creating more of their preferred habitat (secondary forest), the construction of roads used by the logging industry may have a detrimental effect by making these elephants more accessible to poachers as well as the bushmeat and ivory trade.[15] Other threats include habitat loss through the conversion of land to agriculture and increasing competition for resources with growing human populations.[16]

Illegal wildlife trade

Forest elephants are suffering a sharp decline due to poaching for bush meat and ivory for the international ivory trade. Thousands upon thousands of elephants are killed every year to satisfy the illegal international demand for ivory. [37] Around 62% of forest elephants have been slaughtered for their ivory in the last decade alone.[38]

Poaching

Late in the 20th century, conservation workers established a DNA identification system to trace the origin of poached ivory. Due to poaching to meet high demand for ivory, the African forest elephant population approached critical levels in the 1990s and early 2000s.[39][40] Over several decades, numbers are estimated to have fallen from approximately 700,000 to less than 100,000, with about half of the remaining population in Gabon.[41] In May 2013, Sudanese poachers invaded the Central African Republic's Dzanga Bai World Heritage Site and killed 26 elephants.[42][43] Communications equipment, video cameras, and additional training of park guards were provided following the massacre to improve protection of the site.[44] In September 2013, it was estimated that the forest elephant could become extinct within ten years.[45] From mid-April to mid-June 2014, poachers killed 68 elephants in Garamba National Park, including young ones without tusks.[46] According to DNA tests, most forest elephants are poached in Tridom, a border region of Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, and Cameroon.[47][48] At the request of President Ali Bongo Ondimba, twelve British soldiers traveled to Gabon in 2015 to assist in training park rangers following the poaching of many elephants in Minkebe National Park.[49]

There is no ivory that is more desirable than that of the forest elephant. That is due to the facts that ivory that comes from savanna and Asian elephants are softer than the forest elephants. The harder ivory of the forest elephant makes for more enhanced carving and demands a heavier price on the black market. This preference is best evident in Japan; this is where harder ivory has nearly monopolized the trade for some time. Premium quality bachi, a traditional Japanese plucking tool used for string instruments, are contrived exclusively from forest elephants tusks.[50]

In the impenetrable and often trackless expanses of the rain forests of the Congo Basin, poaching is extremely difficult to detect and track. Levels of off-take, for the most part, are estimated from ivory seizures. As protection in East and Southern Africa become more effective, where there are anti-poaching teams and monitoring with small planes for surveillance, the scarcely populated and unprotected forests in Central Africa are most likely becoming increasingly alluring to organized poachers. [50]

Bushmeat trade

It is not ivory alone that drives forest elephant poaching, killing for bushmeat in Central Africa has evolved into an international business in recent decades with markets reaching New York and other major cities of the United States; and the industry is still on the rise. This illegal market poses the greatest threat not only to forest elephants where hunters can target elephants of all ages, including babies, but to all of the larger species in the forests.[50]

There are actions that can be taken to lower the incentive for supplying to the bushmeat market. Regional markets, and the international trade, require the transporting of extensive amounts of animal meat which, in turn, requires the utilization of vehicles. Having checkpoints on major roads and railroads can potentially help disrupt commercial networks.[50]

Civil unrest, human encroachment, and habit fragmentation leaves some elephants confined to small patches of forest without sufficient food. In January 2014, IFAW undertook a relocation project at the request of the Côte d'Ivoire government, moving four elephants from Daloa to Azagny National Park.[51]

Observation

African forest elephants are estimated to constitute up to one-third of the continent's elephant population, but have been poorly studied because of the difficulty in observing them through the dense vegetation that makes up their habitat.[52] Thermal imaging has facilitated observation of the species, leading to more information on their ecology, numbers, and behavior, including their interactions with elephants and other species. Scientists have learned more about how the elephants, who have poor night vision, negotiate their environment using only their hearing and olfactory senses. They also appeared to be much more active sexually during night compared to the day, which was unexpected.[29][30]

References

- ↑ Shoshani, J. (2005). "Order Proboscidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ {{cite journal|title=Threat to African forest elephants|journal=Nature|volume=537|issue=7618|date=2016-09-01|page=7|doi=10.1038/537007b|pmid=275821812

- 1 2 Steenhuysen, Julie (December 22, 2010). "Africa has two species of elephants, not one". Reuters.

- 1 2 3 Morelle, Rebecca (31 August 2016). "Slow birth rate found in African forest elephants". BBC News.

- ↑ Roca, Alfred L.; Georgiadis, Nicholas; Pecon-Slattery, Jill; O'Brien, Stephen J. (24 August 2001). "Genetic Evidence for Two Species of Elephant in Africa". Science. 293 (5534): 1473–1477. PMID 11520983. doi:10.1126/science.1059936.

- ↑ Rohland, Nadin; Reich, David; Mallick, Swapan; Meyer, Matthias; Green, Richard E.; Georgiadis, Nicholas J.; Roca, Alfred L.; Hofreiter, Michael (2010). Penny, David, ed. "Genomic DNA Sequences from Mastodon and Woolly Mammoth Reveal Deep Speciation of Forest and Savanna Elephants". PLoS Biology. 8 (12) (published December 2010). p. e1000564. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000564.

- ↑ Callaway, E. (2016-09-16). "Elephant history rewritten by ancient genomes". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.20622.

- ↑ Debruyne R; van Holt A; Barriel V; Tassy P (2003). "Status of the so-called African pygmy elephant (Loxodonta pumilio (NOACK 1906)): phylogeny of cytochrome b and mitochondrial control region sequences". Comptes Rendus de Biologie. 326 (7): 687–69. PMID 14556388. doi:10.1016/S1631-0691(03)00158-6.

- 1 2 Spinage, C (1994). Elephants. London: T. & A. D. Poyser Ltd.

- ↑ "Forest elephant videos, photos and facts - Loxodonta cyclotis". ARKive. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "African Forest Elephant". The Animal Files. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Loxodonta cyclotis (African forest elephant)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ "WHAT ADAPTATIONS HELP ELEPHANTS KEEP COOL?". PetsonMom. WHALEROCK DIGITAL MEDIA. June 28, 2017. Archived from the original on June 28, 2017.

- ↑ Burnie, D. (2001). Animal. London: Dorling Kindersley.

- 1 2 3 Groning, K.; Saller, M. (1999). Elephants: a Cultural and Natural History. Cologne: Koneman.

- 1 2 3 "Forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis)". Arkive.org/. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Facts About African Elephants - The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore". The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ↑ "Loxodonta cyclotis (African forest elephant)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ "Facts About African Elephants - The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore". The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ↑ "Forest elephant videos, photos and facts - Loxodonta cyclotis". Arkive. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ http://www.mindcomet.com, MindComet, Inc. -. "Behavior". seaworld.org. Retrieved 2017-07-01.

- ↑ Sukumar, R (2003). The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behavior, and Conservation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Morgan, B; Lee, P (2003). "Forest elephant (Loxodonta africana cyclotis) stature in the Reserve de Faune du Petit Loango, Gabon". Journal of Zoology. 259: 337–344. doi:10.1017/s0952836902003291.

- 1 2 3 4 "Forest Elephants - Loxodonta cyclotis". www.birds.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ↑ "A Sight to Behold – Elephant Vision". The Kota Foundation. June 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Loxodonta cyclotis (African forest elephant)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ (Kingdon, 1979; Morgan and Lee, 2003; Roca, et al., 2001)

- ↑ "Loxodonta cyclotis (African forest elephant)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- 1 2 Allen, W (29 May 2006). "Ovulation, Pregnancy, Placentation and Husbandry in the African Elephant (Loxodonta africana)" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 361 (1469): 821–834. PMC 1609400

. PMID 16627297. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1831.

. PMID 16627297. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1831. - 1 2 Turkalo, A.K.; Fay, J.M. (2001). "African Rain Forest Ecology & Conservation". In Weber, W.; White, L.J.T.; Vedder, A.; Naughton-Treves, L. Forest Elephant Behavior and Ecology. Yale University Press. pp. 207–213. ISBN 9780300084337.

- ↑ Campos-Arceiz, Ahimsa; Blake, Steve (November–December 2011). "Megagardeners of the forest – the role of elephants in seed dispersal". Acta Oecologica. Science Direct. 37: 542–553. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2011.01.014.

- ↑ "Seed-dispersal by Elephants in a Tropical Rain Forest in Kahuzi-Biega National Park, Zaire". Biotropica. JSTOR. December 1995. pp. 526–530.

- ↑ Beaune, David; Fruth, Barbara; Bollache, Loïc; Hohmann, Gottfried; Bretagnolle, François (29 December 2012). "Doom of the elephant-dependent trees in a Congo tropical forest". Forest Ecology and Management. 295: 109–117. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.12.041.

- ↑ Blake, Stephen; Deem, Sharon Lynn; Mossimbo, Eric; Maisels, Fiona; Walsh, Peter (25 March 2009). "Forest Elephants: Tree Planters of the Congo". Biotropica: The Journal of Tropical Biology and Conservation. 41 (4): 459–468. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00512.x.

- ↑ White, Lee J.T.; Tutin, Caroline E.G.; Fernandez, Michel (29 April 2008). "Group composition and diet of forest elephants, Loxodonta africana cyclotis Matschie 1900, in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon". African Journal of Ecology. 31 (3): 181–199. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1993.tb00532.x.

- ↑ CITES. "Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species". Cites.org.

- ↑ "African Forest Elephant | Species | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ↑ "Check out the African Forest Elephant". African Wildlife Foundation. 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ↑ Barnes RF, Beardsley K, Michelmore F, Barnes KL, Alers MP, Blom A (1997). "Estimating Forest Elephant Numbers with Dung Counts and a Geographic Information System". The Journal of Wildlife Management. Allen Press. 61 (4): 1384–1393. JSTOR 3802142. doi:10.2307/3802142.

- ↑ Barnes RF, Alers MP, Blom A (1995). "A review of the status of forest elephants Loxodonta africana in central Africa". Biological Conservation. 71 (2): 125–132. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(94)00014-H.

- ↑ Gettleman, Jeffrey (26 December 2012). "In Gabon, Lure of Ivory Is Hard for Many to Resist". The New York Times.

- ↑ "At least 26 elephants massacred in World Heritage site". WWF Global. 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Neme, Laurel (13 May 2013). "Chaos and Confusion Following Elephant Poaching in a Central African World Heritage Site". National Geographic.

- ↑ Joyce, Christopher; McQuay, Bill (9 May 2014). "Former Commando Turns Conservationist To Save Elephants Of Dzanga Bai". NPR.

- ↑ Schiffman, Richard (5 January 2014). "African forest elephants are being massacred into extinction". Salon.com.

- ↑ Schemm, Paul (13 June 2014). "Poachers massacre elephants in Congo park". CTV News. The Associated Press.

- ↑ Jarvis, Brooke (18 June 2015). "DNA From Elephant Dung, Tusks Reveals Poaching Hot Spots". National Geographic.

- ↑ "Tridom". WWF Congo Basin. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ↑ "British troops head to West Africa to help stem elephant slaughter". Belfast Telegraph. 20 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Nishihara, Tomoaki (2012). Demand for forest elephant ivory in Japan. Pachyderm 52:55-65

- ↑ Russo, Christina (29 January 2014). "Success and Tragedy: IFAW’s Project to Relocate Elephants in Côte d’Ivoire". National Geographic.

- ↑ Clabby, Catherine. "Forest Elephant Chronicles". American Scientist. 100 (5): 416–17. doi:10.1511/2012.98.416.

Further reading

- IUCN African Elephant Specialist Group (AfESG): "Statement on the Taxonomy of extant Loxodonta" (February 2006).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Loxodonta cyclotis |

- WCS.org: Forest Elephant Program

- ARKive .org: Images and movies of the forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis)

- BBC Wildlife Finder - video clips from the BBC archive

- PBS Nature: Tracking Forest Elephants

- Elephant Information Repository — in-depth resource on elephants.

- The Elephant Listening Project — information on forest elephants and their vocalizations.

- AWF.org: African Forest Elephant — photos and info.