Equilibrium constant

The equilibrium constant of a chemical reaction is the value of the reaction quotient when the reaction has reached equilibrium. An equilibrium constant value is independent of the analytical concentrations of the reactant and product species in a mixture, but depends on temperature and on ionic strength. Known equilibrium constant values can be used to determine the composition of a system at equilibrium.

For a general chemical equilibrium

- α A + β B … ⇌ ρ R + σ S …

the thermodynamic equilibrium constant can be defined such that, at equilibrium,[1][2]

where curly brackets denote the thermodynamic activities of the chemical species. The right-hand side of this equation corresponds to the reaction quotient Q for arbitrary values of the activities, and becomes the equilibrium constant as shown when the reaction is at equilibrium.

An equilibrium constant is related to the standard Gibbs free energy change for the reaction.

If deviations from ideal behaviour are neglected, the activities of solutes may be replaced by concentrations, [A], and the activity quotient becomes a concentration quotient, Kc.

Kc is defined as equal to the thermodynamic equilibrium constant but with concentrations of reactants and products instead of activities. (Kc appears here to have units of concentration raised to some power while Ko is dimensionless; however as discussed below under Definitions, the concentration factors in Kc are properly divided by a standard concentration so that Kc is dimensionless also.)

Again assuming ideal behavior, the activity of a solvent may be replaced by its mole fraction, or approximately by 1 in dilute solution. The activity of a pure liquid or solid phase is exactly 1. The activity of a species in an ideal gas phase may be replaced by its partial pressure.

A knowledge of equilibrium constants is essential for the understanding of many chemical systems, as well as biochemical processes such as oxygen transport by hemoglobin in blood and acid-base homeostasis in the human body.

Stability constants, formation constants, binding constants, association constants and dissociation constants are all types of equilibrium constant. See also Determination of equilibrium constants for experimental and computational methods.

Types of equilibrium constants

Cumulative and stepwise formation constants

A cumulative or overall constant, given the symbol β, is the constant for the formation of a complex from reagents. For example, the cumulative constant for the formation of ML2 is given by

- M + 2 L ⇌ ML2; [ML2] = β12[M][L]2

The stepwise constant, K, for the formation of the same complex from ML and L is given by

- ML + L ⇌ ML2; [ML2] = K[ML][L] = Kβ11[M][L]2

It follows that

- β12 = Kβ11

A cumulative constant can always be expressed as the product of stepwise constants. There is no agreed notation for stepwise constants, though a symbol such as KL

ML is sometimes found in the literature. It is best always to define each stability constant by reference to an equilibrium expression.

Competition method

A particular use of a stepwise constant is in the determination of stability constant values outside the normal range for a given method. For example, EDTA complexes of many metals are outside the range for the potentiometric method. The stability constants for those complexes were determined by competition with a weaker ligand.

- ML + L′ ⇌ ML′ + L

The formation constant of [Pd(CN)4]2− was determined by the competition method.

Association and dissociation constants

In organic chemistry and biochemistry it is customary to use pKa values for acid dissociation equilibria.

where Kdiss is a stepwise acid dissociation constant. For bases, the base association constant, pKb is used. For any given acid or base the two constants are related by pKa + pKb = pKw, so pKa can always be used in calculations.

On the other hand, stability constants for metal complexes, and binding constants for host–guest complexes are generally expressed as association constants. When considering equilibria such as

- M + HL ⇌ ML + H

it is customary to use association constants for both ML and HL. Also, in generalized computer programs dealing with equilibrium constants it is general practice to use cumulative constants rather than stepwise constants and to omit ionic charges from equilibrium expressions. For example, if NTA, nitrilotriacetic acid, N(CH2CO2H)3 is designated as H3L and forms complexes ML and MHL with a metal ion M, the following expressions would apply for the dissociation constants.

The cumulative association constants can be expressed as

Note how the subscripts define the stoichiometry of the equilibrium product.

Micro-constants

When two or more sites in an asymmetrical molecule may be involved in an equilibrium reaction there are more than one possible equilibrium constants. For example, the molecule L-DOPA has two non-equivalent hydroxyl groups which may be deprotonated. Denoting L-DOPA as LH2, the following diagram shows all the species that may be formed (X = CH2CH(NH2)CO2H):

The first protonation constants are

- [L1H] = k11[L][H], [L2H] = k12[L][H]

The concentration of LH− is the sum of the concentrations of the two micro-species. Therefore, the equilibrium constant for the reaction, the macro-constant, is the sum of the micro-constants.

- K1 = k11 + k12

In the same way,

- K2 = k21 + k22

Lastly, the cumulative constant is

- β2 = K1K2 = k11k21 = k12k22

Thus, although there are seven micro-and macro-constants, only three of them are mutually independent. Moreover, the isomerization constant, Ki, is equal to the ratio of the microconstants.

- Ki = k11/k12

In L-DOPA the isomerization constant is 0.9, so the micro-species L1H and L2H have almost equal concentrations at all pH values.

In general a macro-constant is equal to the sum of all the micro-constants and the occupancy of each site is proportional to the micro-constant. The site of protonation can be very important, for example, for biological activity.

Micro-constants cannot be determined individually by the usual methods, which give macro-constants. Methods which have been used to determine micro-constants include:

- blocking one of the sites, for example by methylation of a hydroxyl group, to determine one of the micro-constants

- using a spectroscopic technique, such as infrared spectroscopy, where the different micro-species give different signals.

- applying mathematical procedures to 13C NMR data.[3][4]

pH considerations (Brønsted constants)

pH is defined in terms of the activity of the hydrogen ion

- pH = −log10 {H+}

In the approximation of ideal behaviour, activity is replaced by concentration. pH is measured by means of a glass electrode, a mixed equilibrium constant, also known as a Brønsted constant, may result.

- HL ⇌ L + H;

It all depends on whether the electrode is calibrated by reference to solutions of known activity or known concentration. In the latter case the equilibrium constant would be a concentration quotient. If the electrode is calibrated in terms of known hydrogen ion concentrations it would be better to write p[H] rather than pH, but this suggestion is not generally adopted.

Hydrolysis constants

In aqueous solution the concentration of the hydroxide ion is related to the concentration of the hydrogen ion by

The first step in metal ion hydrolysis[5] can be expressed in two different ways

It follows that β* = KKW. Hydrolysis constants are usually reported in the β* form and this leads to them appearing to have strange values. For example, if log K = 4 and log KW = −14, log β* = 4 + (−14) = −10. In general when the hydrolysis product contains n hydroxide groups lg β* = log K + n log KW

Conditional constants

Conditional constants, also known as apparent constants, are concentration quotients which are not true equilibrium constants but can be derived from them.[6] A very common instance is where pH is fixed at a particular value. For example, in the case of iron(III) interacting with EDTA, a conditional constant could be defined by

This conditional constant will vary with pH. It has a maximum at a certain pH. That is the pH where the ligand sequesters the metal most effectively.

In biochemistry equilibrium constants are often measured at a pH fixed by means of a buffer solution. Such constants are, by definition, conditional and different values may be obtained when using different buffers.

Gas-phase equilibria

For equilibria in a gas phase, fugacity, f, is used in place of activity. However, fugacity has the dimension of pressure, so it must be divided by a standard pressure, usually 1 bar, in order to produce a dimensionless quantity, f/po. An equilibrium constant is expressed in terms of the dimensionless quantity. For example, for the equilibrium 2NO2 ⇌ N2O4,

Fugacity is related to partial pressure, p, by a dimensionless fugacity coefficient ϕ: f = ϕp. Thus, for the example,

Usually the standard pressure is omitted from such expressions. Expressions for equilibrium constants in the gas phase then resemble the expression for solution equilibria with fugacity coefficient in place of activity coefficient and partial pressure in place of concentration.

Thermodynamics

Definitions

For a general chemical equilibrium

- α A + β B … ⇌ ρ R + σ S …

the thermodynamic definition of the equilibrium constant is that, at equilibrium,

where {A} is the activity, at equilibrium, of the chemical species A, etc.[7]

It is conventional to put the activities of the products in the numerator and those of the reactants in the denominator. Since activity is a dimensionless quantity, the thermodynamic equilibrium constant, Ko, is also a dimensionless quantity. This is important because Ko is related to the standard free energy change, ΔGo, for the reaction.

- ΔG

o= −RT ln Ko

R is the gas constant and T the absolute or thermodynamic temperature. Taking the logarithm of Ko is only possible when Ko has no dimensions, that is, when it is a pure (positive) number. However it is often more convenient to use concentrations (or partial pressures in the gas phase) than activities, so the equilibrium expression may be written as the product of three components, a reaction quotient of equilibrium concentrations, QE, a quotient of activity factors, Γ, and a quotient of standard concentrations, C0.

The symbol [A] stands for a generalized concentration or partial pressure of the chemical species A, The activity coefficients, γ, are dimensionless and co

A stands for the standard concentration or standard partial pressure. By convention the standard concentrations have a value of 1 mol/dm3 (or 1 atm), so the third factor, C0, has a numerical value of 1 and units that are the reciprocal of the units of the concentration quotient. Ko remains dimensionless. so the expression simplifies to

It follows that the "Concentration constant", Kc, is related to the thermodynamic equilibrium constant by

Note that when Kc is defined in this way it has no dimension, so log Kc is permissible.

When an equilibrium constant value is to be determined, there are three options for dealing with the activity coefficients.

- Use known or calculated activity coefficients, together with concentrations of reactants. For equilibria in solution estimates of the activity coefficients of charged species can be obtained using Debye–Hückel theory, an extended version, or SIT theory. For uncharged species, the activity coefficient γ0 mostly follows a "salting-out" model: log10 γ0 = bI where I stands for ionic strength.[8]

- Assume that the activity coefficients are all equal to 1. This is acceptable when all species are uncharged and the solvent has low polarity.

- For equilibria in solution use a medium of high ionic strength. In effect this redefines the standard state as referring to the medium. Activity coefficients in the standard state are, by definition, equal to 1. The value of an equilibrium constant determined in this manner is dependent on the ionic strength. When published constants refer to an ionic strength other than the one required for a particular application, they may be adjusted by means of specific ion theory (SIT) and other theories.[9]

Dimensionality

Any equilibrium constant, K, must be dimensionless. An equilibrium constant is related to the standard Gibbs free energy change for the reaction by the expression

This requires that K be a pure number from which a logarithm can be derived. In the case of a simple equilibrium

the thermodynamic equilibrium constant is defined in terms of the activities, {AB}, {A} and {B}, of the species in equilibrium with each other.

As activity is a dimensionless quantity, K is dimensionless.

Now, each activity term can be expressed as a product of a concentration [X] and a corresponding activity coefficient, . Therefore,

Since each activity coefficient has the dimension 1/concentration, K remains dimensionless. However, when the quotient of activity coefficients is set equal to 1, K appears to have the dimension of 1/concentration.

This is what usually happens in practice when an equilibrium constant is calculated as a quotient of concentration values. The assumption underlying this practice is that the quotient of activities is constant under the conditions in which the equilibrium constant value is determined. There conditions are usually achieved by keeping the reaction temperature constant and by using a medium of relatively high ionic strength as the solvent. It is not unusual, particularly in texts relating to biochemical equilibria, to see a value quoted with a dimension. The justification for this practice is that the concentration scale used may be either mol dm−3 or mmol dm−3, so that the concentration unit has to be stated in order to avoid there being any ambiguity.

In general equilibria between two reagents can be expressed as

in which case the equilibrium constant is defined, in terms of numerical concentration values, as

The apparent dimension of this K value is concentration1−p−q; this may be written as M(1−p−q) or mM(1−p−q), where the symbol M signifies a molar concentration (1 M = 1 mol dm−3)

A further complications arises from the fact that an equilibrium constant can be defined as an association constant or as a dissociation constant. For dissociation constants

- ;

The apparent dimension associated with a dissociation constant is the reciprocal of the dimension associated with the corresponding association constant.

Derivation of equilibrium constant expression

Temperature, T, is assumed to be constant in the following treatment.

Thermodynamic equilibrium is characterized by the free energy for the whole (closed) system being a minimum. For systems at constant temperature and pressure the Gibbs free energy is minimum.[10] The slope of the reaction free energy, δGr with respect to the reaction coordinate, ξ, is zero when the free energy is at its minimum value.

The free energy change, δGr, can be expressed as a weighted sum of chemical potentials, the partial molar free energies of the species in equilibrium. The potential, μi, of the ith species in a chemical reaction is the partial derivative of the free energy with respect to the number of moles of that species, Ni

A general chemical equilibrium can be written as

- ≈ α A + β B … ⇌ ρ R + σ S …

where nj are the stoichiometric coefficients of the reactants in the equilibrium equation, and mj are the coefficients of the products. The value of δGr for these reactions is a function of the chemical potentials of all the species.

The chemical potential, μi, of the ith species can be calculated in terms of its activity, ai.

μo

i is the standard chemical potential of the species, R is the gas constant and T is the temperature. Setting the sum for the reactants j to be equal to the sum for the products, k, so that δGr(Eq) = 0

Rearranging the terms,

This relates the standard Gibbs free energy change, ΔGo to an equilibrium constant, K, the reaction quotient of activity values at equilibrium.

Temperature dependence

The van 't Hoff equation:

shows that when the reaction is exothermic (ΔHo is negative), then K decreases with increasing temperature, in accordance with Le Chatelier's principle. It permits calculation of the reaction equilibrium constant at temperature T2 if the reaction constant at T1 is known and the standard reaction enthalpy can be assumed to be independent of temperature even though each standard enthalpy change is defined at a different temperature. However, this assumption is valid only for small temperature differences T2 − T1. In fact standard thermodynamic arguments can be used to show that

where Cp is the heat capacity at constant pressure. The equilibrium constant is related to the standard Gibbs energy change of reaction as

where ΔGo is the standard Gibbs free energy change of reaction, R is the gas constant, and T the absolute temperature.

If the equilibrium constant has been determined and the standard reaction enthalpy has also been determined, by calorimetry, for example, this equation allows the standard entropy change for the reaction to be derived.

A more complex formulation

The calculation of K at a particular temperature from a known K at another given temperature can be approached as follows if standard thermodynamic properties are available. The effect of temperature on equilibrium constant is equivalent to the effect of temperature on Gibbs energy because:

where ΔrGo is the reaction standard Gibbs energy, which is the sum of the standard Gibbs energies of the reaction products minus the sum of standard Gibbs energies of reactants.

Here, the term "standard" denotes the ideal behaviour (i.e., an infinite dilution) and a hypothetical standard concentration (typically 1 mol/kg). It does not imply any particular temperature or pressure because, although contrary to IUPAC recommendation, it is more convenient when describing aqueous systems over wide temperature and pressure ranges.[11]

The standard Gibbs energy (for each species or for the entire reaction) can be represented (from the basic definitions) as:

In the above equation, the effect of temperature on Gibbs energy (and thus on the equilibrium constant) is ascribed entirely to heat capacity. To evaluate the integrals in this equation, the form of the dependence of heat capacity on temperature needs to be known.

If the standard molar heat capacity Co

p can be approximated by some analytic function of temperature (e.g. the Shomate equation), then the integrals involved in calculating other parameters may be solved to yield analytic expressions for them. For example, using approximations of the following forms:[12]

- For pure substances (solids, gas, liquid):

- For ionic species at T < 200 °C:

then the integrals can be evaluated and the following final form is obtained:

The constants A, B, C, a, b and the absolute entropy, S̆ o

298 K, required for evaluation of Co

p(T), as well as the values of G298 K and S298 K for many species are tabulated in the literature.

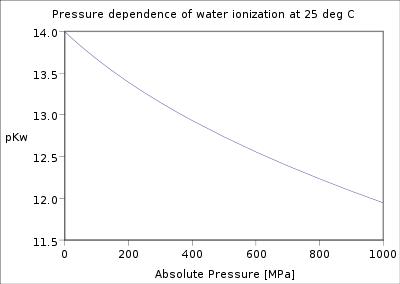

Pressure dependence

The pressure dependence of the equilibrium constant is usually weak in the range of pressures normally encountered in industry, and therefore, it is usually neglected in practice. This is true for condensed reactant/products (i.e., when reactants and products are solids or liquid) as well as gaseous ones.

For a gaseous-reaction example, one may consider the well-studied reaction of hydrogen with nitrogen to produce ammonia:

- N2 + 3 H2 ⇌ 2 NH3

If the pressure is increased by an addition of an inert gas, then neither the composition at equilibrium nor the equilibrium constant are appreciably affected (because the partial pressures remain constant, assuming an ideal-gas behaviour of all gases involved). However, the composition at equilibrium will depend appreciably on pressure when:

- the pressure is changed by compression of the gaseous reacting system, and

- the reaction results in the change of the number of moles of gas in the system.

In the example reaction above, the number of moles changes from 4 to 2, and an increase of pressure by system compression will result in appreciably more ammonia in the equilibrium mixture. In the general case of a gaseous reaction:

- α A + β B ⇌ σ S + τ T

the change of mixture composition with pressure can be quantified using:

where p denote the partial pressures of the components, P is the total system pressure, X denote the mole fraction, Kp is the equilibrium constant expressed in terms of partial pressures and KX is the equilibrium constant expressed in terms of mole fractions.

The above change in composition is in accordance with Le Chatelier's principle and does not involve any change of the equilibrium constant with the total system pressure. Indeed, for ideal-gas reactions Kp is independent of pressure.[13]

In a condensed phase, the pressure dependence of the equilibrium constant is associated with the reaction molar volume.[14] For reaction:

- α A + β B ⇌ σ S + τ T

the reaction molar volume is:

where V̄ denotes a partial molar volume of a reactant or a product.

For the above reaction, one can expect the change of the reaction equilibrium constant (based either on mole-fraction or molal-concentration scale) with pressure at constant temperature to be:

The matter is complicated as partial molar volume is itself dependent on pressure.

Effect of isotopic substitution

Isotopic substitution can lead to changes in the values of equilibrium constants, especially if hydrogen is replaced by deuterium (or tritium).[15] This equilibrium isotope effect is analogous to the kinetic isotope effect on rate constants, and is primarily due to the change in zero-point vibrational energy of H–X bonds due to the change in mass upon isotopic substitution.[15] The zero-point energy is inversely proportional to the square root of the mass of the vibrating hydrogen atom, and will therefore be smaller for a D–X bond that for an H–X bond.

An example is a hydrogen atom abstraction reaction R' + H–R ⇌ R'–H + R with equilibrium constant KH, where R' and R are organic radicals such that R' forms a stronger bond to hydrogen than does R. The decrease in zero-point energy due to deuterium substitution will then be more important for R'–H than for R–H, and R'–D will be stabilized more than R–D, so that the equilibrium constant KD for R' + D–R ⇌ R'–D + R is greater than KH. This is summarized in the rule the heavier atom favors the stronger bond.[15]

Similar effects occur in solution for acid dissociation constants (Ka) which describe the transfer of H+ or D+ from a weak aqueous acid to a solvent molecule: HA + H2O = H3O+ + A– or DA + D2O ⇌ D3O+ + A–. The deuterated acid is studied in heavy water, since if it were dissolved in ordinary water the deuterium would rapidly exchange with hydrogen in the solvent.[15]

The product species H3O+ (or D3O+) is a stronger acid than the solute acid, so that it dissociates more easily and its H–O (or D–O) bond is weaker than the H–A (or D–A) bond of the solute acid. The decrease in zero-point energy due to isotopic substitution is therefore less important in D3O+ than in DA so that KD < KH, and the deuterated acid in D2O is weaker than the non-deuterated acid in H2O. In many cases the difference of logarithmic constants pKD – pKH is about 0.6,[15] so that the pD corresponding to 50% dissociation of the deuterated acid is about 0.6 units higher than the pH for 50% disssociation of the non-deuterated acid.

See also

References

- ↑ Rossotti, F. J. C.; Rossotti, H. (1961). The Determination of Stability Constants. McGraw-Hill. p. 5.

- ↑ IUPAC (2011). Green Book (PDF) (3rd ed.). p. 58.

- ↑ Hague, David N.; Moreton, Anthony D. (1994). "Protonation sequence of linear aliphatic polyamines by 13C NMR spectroscopy". J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 (2): 265–70. doi:10.1039/P29940000265.

- ↑ Borkovec, Michal; Koper, Ger J. M. (2000). "A Cluster Expansion Method for the Complete Resolution of Microscopic Ionization Equilibria from NMR Titrations". Anal. Chem. 72 (14): 3272–9. PMID 10939399. doi:10.1021/ac991494p.

- ↑ Baes, C. F.; Mesmer, R. E. (1976). The Hydrolysis of Cations. Wiley.

- ↑ Schwarzenbach, G.; Flaschka, H. (1969). Complexometric titrations. Methuen.

- ↑ Rossotti, F. J. C.; Rossotti, H. (1961). "Chapter 2: Activity and Concentration Quotients". The Determination of Stability Constants. McGraw–Hill.

- ↑ Butler, J. N. (1998). Ionic Equilibrium. John Wiley and Sons.

- ↑ "Project: Ionic Strength Corrections for Stability Constants". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ↑ Denbigh, K. (1981). "Chapter 4". The principles of chemical equilibrium (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28150-4.

- ↑ Majer, V.; Sedelbauer, J.; Wood (2004). "Calculations of standard thermodynamic properties of aqueous electrolytes and nonelectrolytes". In Palmer, D. A.; Fernandez-Prini, R.; Harvey, A. Aqueous Systems at Elevated Temperatures and Pressures: Physical Chemistry of Water, Steam and Hydrothermal Solutions. Elsevier.

- ↑ Roberge, P. R. (November 2011). "Appendix F". Handbook of Corrosion Engineering. McGraw-Hill. p. 1037ff.

- ↑ Atkins, P. W. (1978). Physical Chemistry, (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 210.

- ↑ Van Eldik, R.; Asano, T.; Le Noble, W. J. (1989). "Activation and reaction volumes in solution. 2". Chem. Rev. 89 (3): 549–688. doi:10.1021/cr00093a005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Laidler K.J. Chemical Kinetics (3rd ed., Harper & Row 1987), p.428–433 ISBN 0-06-043862-2

Data sources

- IUPAC SC-Database A comprehensive database of published data on equilibrium constants of metal complexes and ligands

- NIST Standard Reference Database 46: Critically selected stability constants of metal complexes

- Inorganic and organic acids and bases pKa data in water and DMSO

- NASA Glenn Thermodynamic Database webpage with links to (self-consistent) temperature-dependent specific heat, enthalpy, and entropy for elements and molecules

External links

- Science Aid: Equilibrium Constants Explanation of Kc and Kp for high-school level