Carnitine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | <10% |

| Protein binding | None |

| Metabolism | slightly |

| Excretion | Urine (>95%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H15NO3 |

| Molar mass | 161.199 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

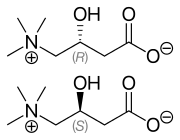

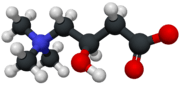

Carnitine (β-hydroxy-γ-N-trimethylaminobutyric acid, 3-hydroxy-4-N,N,N- trimethylaminobutyrate) is a quaternary ammonium compound[1] involved in metabolism in most mammals, plants and some bacteria.[2] Carnitine may exist in two isomers, labeled D-carnitine and L-carnitine, as they are optically active. At room temperature, pure carnitine is a white powder, and a water-soluble zwitterion with low toxicity. Carnitine only exists in animals as the L-enantiomer, and D-carnitine is toxic because it inhibits the activity of L-carnitine.[3] Carnitine was discovered in 1905 as a result of its high concentration in muscle tissue. It was originally labeled vitamin BT; however, because carnitine is synthesized in the human body, it is no longer considered a vitamin.[2] Carnitine can be synthesized by most humans; about 1 in 350 males is unable to synthesize it due to genetic causes on the X chromosome.[4][5] Carnitine is involved in the oxidation of fatty acids, and involved in systemic primary carnitine deficiency. It has been studied for preventing and treating other conditions, and is used as a purported performance enhancing drug.[1]

Biosynthesis and metabolism

Many eukaryotes have the ability to synthesize carnitine, including humans. Humans synthesize carnitine from the substrate TML (6-N-trimethyllysine), which is in turn derived from the methylation of the amino acid lysine. TML is then hydroxylated into hydroxytrimethyllysine (HTML) by trimethyllysine dioxygenase, requiring the presence of ascorbic acid. HTML is then cleaved by HTML aldose, yielding 4-trimethylaminobutyraldehyde (TMABA) and glycine. TMABA is then dehydrogenated into gamma-butyrobetaine, in an NAD+-dependent reaction, catalyzed by TMABA dehydrogenase. Gamma-butyrobetaine is then hydroxylated by gamma butyrobetaine hydroxylase into L-carnitine, requiring iron in the form of Fe2+.[6]

Carnitine is involved in transporting fatty acids across the mitochondrial membrane, by forming a long chain acetylcarnitine ester and being transported by carnitine palmitoyltransferase I and carnitine palmitoyltransferase II.[7] Carnitine also plays a role in stabilizing Acetyl-CoA and coenzyme A levels through the ability to receive or give an acetyl group.[8]

Physiological effects

Deficiency

Carnitine deficiency caused by a genetic defect in carnitine transport occurs in roughly 1 in 50,000 in the US. Systemic primary carnitine deficiency (SPDC) is characterized by various cardiological, metabolic and musculoskeletal symptoms that vary widely in age of onset and presentation. Prognosis is generally good with carnitine supplementation.[9]

Secondary carnitine deficiency may occur due to conditions such as malnutrition, poor absorption or access to only vegetables.[7]

Supplementation

Some research has been carried out on carnitine supplementation in athletes, given its role in fatty acid metabolism; however, individual responses varied significantly in the 300 people involved in one study.[8] Carnitine has been studied in various cardiometabolic conditions, with a bit of evidence pointing towards efficacy as an adjunct in heart disease and diabetes. However, there are insufficient trials to determine its efficacy.[10] Carnitine has no effect on preventing mortality associated with cardiovascular conditions.[11] Carnitine has no effect on serum lipids, except a possible lowering of LDL[12] Carnitine has no effect on most parameters in end stage kidney disease, however it possibly has an effect on c-reactive protein. The effects on mortality and disease outcome are unknown.[13]

Male infertility

The carnitine content of seminal fluid is directly related to sperm count and motility, suggesting that the compound might be of value in treating male infertility. Several studies indicate that carnitine supplementation (2–3 grams/day for 3–4 months) may improve sperm quality, and one randomized, double-blind crossover trial found that 2 grams/day of carnitine taken for 2 months by 100 infertile men increased the concentration and both total and forward motility of their sperm. The reported benefits may relate to increased mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation (providing more energy for sperm) and reduced cell death in the testes.

Atherosclerosis

An important interaction between diet and the intestinal microbiome brings into play additional metabolic factors that aggravate atherosclerosis beyond dietary cholesterol. This may help to explain some benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Hazen’s group from the Cleveland Clinic reported that carnitine[14] from animal flesh (four times as much in red meat as in fish or chicken), as well as phosphatidylcholine from egg yolk, are converted by intestinal bacteria to trimethylamine (the compound that causes uremic breath to smell fishy). Trimethylamine is oxidized in the liver to trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), which causes atherosclerosis in animal models. Patients in the top quartile of TMAO had a 2.5-fold increase in the 3-year risk of stroke, death, or myocardial infarction.

A key issue is that vegans who consumed L-carnitine did not produce TMAO because they did not have the intestinal bacteria that produce TMA from carnitine.[15]

Sources

Food

What foods provide carnitine?

Animal products like meat, fish, poultry, and milk are the best sources. In general, the redder the meat, the higher its carnitine content. Dairy products contain carnitine primarily in the whey fraction, in small amounts relative to red meat.[16][17][18] The carnitine content of several foods is listed in Table 1.

| Food | Milligrams (mg) |

|---|---|

| Beef steak, cooked, 4 ounces | 56–162 |

| Ground beef, cooked, 4 ounces | 87–99 |

| Milk, whole, 1 cup | 8 |

| Codfish, cooked, 4 ounces | 4–7 |

| Chicken breast, cooked, 4 ounces | 3–5 |

| Ice cream, ½ cup | 3 |

| Cheese, cheddar, 2 ounces | 2 |

| Whole–wheat bread, 2 slices | 0.2 |

| Asparagus, cooked, ½ cup | 0.1 |

Carnitine occurs in two forms, known as D and L, that are mirror images (isomers) of each other. Only L-carnitine is active in the body and is the form found in food [1,6]. [19][20][21] However, even strict vegetarians (vegans) show no signs of carnitine deficiency, despite the fact that most dietary carnitine is derived from animal sources.[22][23] No advantage appears to exist in giving an oral dose greater than 2 g at one time, since absorption studies indicate saturation at this dose.[24]

Health Canada

Other sources may be found in over-the-counter vitamins, energy drinks and various other products. Products containing L-carnitine can now be marketed as "natural health products" in Canada. As of 2012, Parliament has allowed carnitine products and supplements to be imported into Canada (Health Canada). The Canadian government did issue an amendment in December 2011 allowing the sale of L-carnitine without a prescription.[25]

History

Levocarnitine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a new molecular entity under the brand name Carnitor on December 27, 1985.[26]

See also

- Acetylcarnitine

- Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase

- Glycine Propionyl-L-Carnitine (GPLC)

- Meldonium

- Systemic primary carnitine deficiency

References

- 1 2 Karlic, Heidrun; Lohninger, Alfred (1 July 2004). "Supplementation of l-carnitine in athletes: does it make sense?". Nutrition. 20 (7-8): 709–715. ISSN 0899-9007. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.003.

- 1 2 Bremer, J. (1 October 1983). "Carnitine--metabolism and functions". Physiological Reviews. 63 (4): 1420–1480. ISSN 0031-9333. PMID 6361812.

- ↑ Harmeyer, J. "The Phystiological Role of L-Carntine" (PDF). Lohmann Information.

- ↑ Patrícia B. S. Celestino-Soper et al., A common X-linked inborn error of carnitine biosynthesis may be a risk factor for nondysmorphic autism, PNAS 109(21), 2012, pp. 7974–7981. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120210109 , http://www.pnas.org/content/109/21/7974.full

- ↑ Researchers investigate possible link between carnitine deficiency and autism, https://medicalxpress.com/news/2017-07-link-carnitine-deficiency-autism.html

- ↑ Strijbis, Karin; Vaz, Frédéric M.; Distel, Ben (1 May 2010). "Enzymology of the carnitine biosynthesis pathway". IUBMB Life. 62 (5): 357–362. ISSN 1521-6551. doi:10.1002/iub.323.

- 1 2 Flanagan, Judith L; Simmons, Peter A; Vehige, Joseph; Willcox, Mark DP; Garrett, Qian (16 April 2010). "Role of carnitine in disease". Nutrition & Metabolism. 7: 30. ISSN 1743-7075. PMC 2861661

. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-7-30.

. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-7-30. - 1 2

- ↑ Magoulas, Pilar L.; El-Hattab, Ayman W. (1 January 2012). "Systemic primary carnitine deficiency: an overview of clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 7: 68. ISSN 1750-1172. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-68.

- ↑ Mingorance, Carmen; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Rosalía; Justo, María Luisa; Álvarez de Sotomayor, María; Herrera, María Dolores (1 January 2011). "Critical update for the clinical use of L-carnitine analogs in cardiometabolic disorders". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 7: 169–176. ISSN 1176-6344. PMC 3072740

. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S14356.

. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S14356. - ↑ Shang, Ruiping; Sun, Zhiqi; Li, Hui (21 July 2014). "Effective dosing of L-carnitine in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 14: 88. ISSN 1471-2261. PMID 25044037. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-14-88.

- ↑ Huang, Haohai; Song, Lijun; Zhang, Hua; Zhang, Hanbin; Zhang, Jiping; Zhao, Wenchang (1 January 2013). "Influence of L-carnitine supplementation on serum lipid profile in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Kidney & Blood Pressure Research. 38 (1): 31–41. ISSN 1423-0143. PMID 24525835. doi:10.1159/000355751.

- ↑ Chen, Yizhi; Abbate, Manuela; Tang, Li; Cai, Guangyan; Gong, Zhixiang; Wei, Ribao; Zhou, Jianhui; Chen, Xiangmei (1 February 2014). "L-Carnitine supplementation for adults with end-stage kidney disease requiring maintenance hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 99 (2): 408–422. ISSN 1938-3207. PMID 24368434. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.062802.

- ↑ Koeth, RA; Wang, Z; Levison, BS; et al. (2013). "Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis". Nat Med. 19 (5): 576–85.

- ↑ Spence, J. David (Last updated: 28 JUL 2016). "REVIEW, Recent advances in pathogenesis, assessment, and treatment of atherosclerosis [version 1; referees: 3 approved]" (PDF). F1000Research 2016. 5(F1000 Faculty Rev):1880. ISSN 1938-3207. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Rebouche CJ. Carnitine. In: Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 9th Edition (edited by Shils ME, Olson JA, Shike M, Ross, AC). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, New York, 1999, pp. 505-12.

- ↑ Carnitine: lessons from one hundred years of research. Ann NY Acad Sci 2004;1033:ix-xi.

- ↑ National Research Council. Food and Nutrition Board. Recommended Dietary Allowances, 10th Edition. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1989.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes. 2005. http://www.iom.edu/project.asp?id=4574

- ↑ Stanley CA. Carnitine deficiency disorders in children. Ann NY Acad Sci 2004;1033:42-51.

- ↑ Rebouche CJ. Kinetics, pharmacokinetics, and regulation of L-carnitine and acetyl-L-carnitine metabolism. Ann NY Acad Sci 2004;1033:30-41.

- ↑ "L-Carnitine – Linus Pauling Institute – Oregon State University".

- ↑ Lombard, K. A.; Olson, A. L.; Nelson, S. E.; Rebouche, C. J. (1989-08-01). "Carnitine status of lactoovovegetarians and strict vegetarian adults and children". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 50 (2): 301–306. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 2756917.

- ↑ Bain, Marcus A.; Milne, Robert W.; Evans, Allan M. (2006-10-01). "Disposition and metabolite kinetics of oral L-carnitine in humans". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 46 (10): 1163–1170. ISSN 0091-2700. PMID 16988205. doi:10.1177/0091270006292851.

- ↑ "Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations".

- ↑ FDA approval letter

Further reading

The following are good secondary sources on the subject of this article.

- Bremer, J (1983). "Carnitine—Metabolism and Functions". Physiol. Rev. 63 (4): 1420–1480. PMID 6361812. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Stanley, Charles A.; Bennett, Michael J.; Longo, Nicolo (2000). "Plasma Membrane Carnitine Transport Defect". In Scriver, C.W.; Beaudet, A.L.; Sly, W.S.; Valle, D. Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (8th ed.). New York, NY, USA: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-913035-6. doi:10.1036/ommbid.297. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Steiber A.; J. Kerner; C. Hoppel (2004). "Carnitine: a Nutritional, Biosynthetic, and Functional perspective". Mol. Aspects Med. 25 (5–6): 455–73. PMID 15363636. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2004.06.006.

- Marcovina, S. M.; Sirtori, C.; Peracino, A.; Gheorghiade, M.; Borum, P.; Remuzzi, G.; Ardehali, H. (2013). "Translating the Basic Knowledge of Mitochondrial Functions to Metabolic Therapy: Role of L-Carnitine". Translational Research. 161 (2): 73–84. PMC 3590819

. PMID 23138103. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2012.10.006.

. PMID 23138103. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2012.10.006. - Johri, A.M.; D.K. Heyland; M.F. Hétu; B. Crawford & J.D. Spence (2014). "Carnitine Therapy for the Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence and Controversies" (print, online review). Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 24 (8, Aug.): 808–814. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2014.03.007. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Dambrova, M.; E. Liepinsh (2015). "Risks and Benefits of Carnitine Supplementation in Diabetes" (print, online review). Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 123 (2, Feb.): 95–100. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1390481. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Brown, J. Mark; Stanley L. Hazen (2015). "The Gut Microbial Endocrine Organ: Bacterially Derived Signals Driving Cardiometabolic Diseases". Annu. Rev Med. 66: 343–359. PMC 4456003

. PMID 25587655. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205.

. PMID 25587655. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205.

External links

- National Institutes of Health fact sheet on carnitine

- Molecule of the Month at University of Bristol