Action role-playing game

| Part of a series on |

| Role-playing video games |

|---|

| Subgenres |

| Topics |

| Lists |

Action role-playing video games (abbreviated action RPG or ARPG) are a subgenre of role-playing video games. The games emphasize real-time combat (where the player has direct control over characters) over turn-based or menu-based combat. These games often use action game combat systems similar to hack and slash or shooter games.

Action role-playing games may also incorporate action-adventure games, which iclude a mission system and RPG mechanics, or massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) with real-time combat systems.

Early real-time elements

Early dungeon-crawl video games used turn-based movement, whereby the player and enemy took turns to perform actions.[1]:234–2355 Dungeons of Daggorath, released for the TRS-80 Color Computer in 1982, combined a typical first-person dungeon crawl with real-time elements, requiring timed keyboard commands and containing enemies that move independently of the player.[2] The game lacked numerical statistics such as hit points or vitality, instead using an arcade-like fatigue system with a pulsating heart indicating the player's health.[1]:80–81 This concept was inspired by the 1978 arcade game Space Invaders, where a heartbeat-like sound gradually increases pace as enemies advance towards the player.[3]:232

In 1983, ASCII released the Sharp X1 computer game Bokosuka Wars,[4] considered an early example of both an action role-playing game[5][6] and a tactical role-playing game.[7] In Bokosuka Wars, while the action occurred entirely in real-time, [8] each soldier was able to gain experience and level up through battle.[7]

That same year, Nihon Falcom released Panorama Toh (Panorama Island) for the PC-88. It was developed by Yoshio Kiya, who would go on to create the Dragon Slayer and Brandish series of action role-playing games. While its role-playing elements were limited, lacking traditional statistical or leveling systems, the game featured real-time combat with a gun, bringing it closer to Falcom's later action role-playing formula. The game's desert island overworld also featured a day-night cycle, non-player characters the player could attack or converse with, and a basic survival mechanic – the player had to find and consume rations to restore hit points lost with each action.[9]

Early action role-playing games and hack and slash

Early 1980s

While Western computer developers explored the possibilities of real-time role-playing gameplay to a limited extent,[1]:234 Japanese developers created a new brand of action role-playing game. These new games combined the role-playing genre with arcade-style action and action-adventure elements.[10][11]

Action RPGs were first popularized by The Tower of Druaga,[11] an arcade game released by Namco in June 1984. It was conceived as a "fantasy Pac-Man" with combat, puzzle-solving, and subtle RPG elements.[12] Its success in Japan inspired the near-simultaneous development of three early action role-playing games: Dragon Slayer, Courageous Perseus, and Hydlide. Each of these games combined Druaga's real-time hack-and-slash gameplay with more RPG mechanics.

A rivalry developed between the three games, with Dragon Slayer and Hydlide continuing their rivalry through subsequent sequels.[13]:38–49 The Tower of Druaga, Dragon Slayer and Hydlide were influential in Japan, where they laid the foundations for the action RPG genre and influenced titles such as Ys and The Legend of Zelda.[13]:38[14]

The company most often credited as the pioneer of the new action role-playing genre is Nihon Falcom, producers of the Dragon Slayer series, who earned a reputation as the progenitor of the action role-playing genre.[15] Dragon Slayer was created by Yoshio Kiya,[14] who built on the action role-playing elements of his previous game Panorama Toh,[9] as well as The Tower of Druaga.[11]

Falcom's Dragon Slayer series abandoned the command-based battles of earlier role-playing games in favor of real-time hack-and-slash combat that required direct input from the player, alongside puzzle-solving elements. The original Dragon Slayer,[14] originally released for the PC-8801 computer in September 1984,[16] is one of the first action-RPGs.[15][17] In contrast to earlier turn-based roguelikes, Dragon Slayer was a dungeon-crawl role-playing game using real-time, action-oriented combat,[17] combined with traditional role-playing mechanics.[11] Dragon Slayer also featured an in-game map to help with the dungeon crawling, required item management due to the inventory being limited to one item at a time,[14] and featured the use of item-based puzzles similar to The Legend of Zelda.[15] Dragon Slayer's overhead action role-playing formula was used in many later games.[18]

Another early action role-playing game was Courageous Perseus,[19] released by Cosmos Computers for Japanese computers in September 1984, the same month as Dragon Slayer.[20] It was technically more advanced than both Dragon Slayer and Hydlide,[20] featuring more advanced graphics,[13]:38–49 exploration on a large desert island, raft transport for sea travel to smaller isles, and a wide variety of items and monsters. However, it was not as well-received, as it relied heavily on level grinding, and included a health-draining mechanic where the player lost one hit point every second.[20]

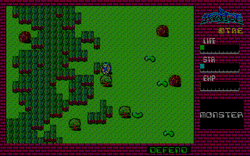

T&E Soft's Hydlide, released in December 1984,[21] was created by Tokihiro Naito, who was influenced by The Tower of Druaga.[13]:42–49 Hydlide was an early open-world game,[22] rewarding exploration in an open-world environment.[23] It also featured innovations such as the ability to switch between the attack and defense mode, a quick save and load option (which can be done at any moment of the game through the use of passwords), and a health regeneration mechanic where health and magic slowly regenerate when standing still.[24][25][26] The game was immensely popular in Japan, selling 2 million copies across all platforms.[19]

Another early action role-playing game was Namco's 1984 arcade release Dragon Buster,[27] which featured a life meter, called "Vitality" in-game.[28] It also introduced side-scrolling platform elements and a "world view" map similar to Super Mario Bros., released the following year.[29]

Dragon Slayer II: Xanadu, released in 1985 (billed as a "new type real-time role-playing game"), was an action role-playing game including many character stats and a large quest.[17][30] It also incorporated a side-scrolling view during exploration and an overhead view during battle,[18] though some rooms were also explored using an overhead view. The game allowed the player to visit towns, training facilities within those towns for improvement of statistics, and shops that sell items – equipment that changes the player character's visible appearance, and food that is consumed slowly over time, which is essential for keeping the player alive. It also introduced gameplay mechanics such as platform jumping, magic that could be used to attack enemies from a distance,[17] individual experience for equipped items,[30] and an early "Karma" morality system where the character's Karma meter will rise if he commits sin (killing "good" enemies), which in turn causes the temples to refuse to level him up.[17][30] It is also considered a "proto-Metroidvania" game,[31] due to being an "RPG turned on its side" that allowed players to run, jump, collect, and explore.[32] The game was popular in Japan.[30]

Tritorn, released by Zainsoft for Japanese computers in 1985, was a side-scrolling, platformer-action RPG hybrid (much like Xanadu), released in the same month. Tritorn had fewer RPG elements than Xanadu, instead focusing more on action. Tritorn was influenced by Hydlide and Dragon Buster.[13]

Hydlide II: Shine of Darkness, released in 1985,[33] introduced a morality meter, where the player could be aligned with Justice, Normal, or Evil, depending on which monsters or humans the player kills. Each alignment leads to different outcomes, such as townsfolk ignoring players with an evil alignment and denying access to certain clues, dialogues, equipment, and training. The game also introduced a time option, allowing the player to speed up or slow down the gameplay.[24]

Magical Zoo's The Screamer, a 1985 post-apocalyptic cyberpunk horror role-playing game released for the PC-8801,[34][35][36] featured gameplay that switched between first-person dungeon crawl exploration and side-scrolling shooter combat, where the player could jump, duck and shoot at enemies in real time.[36]

Xanadu Scenario II, released in 1986, was an early example of an expansion pack, created to expand the content of Dragon Slayer II: Xanadu.[18] The way the Dragon Slayer series reworked the entire game system of each installment later influenced the Final Fantasy franchise, which would do the same for each of its installments.[37] According to Dragon Slayer creator Yoshio Kiya in a 1987 interview, when he developed Dragon Slayer, he "wanted to make something new", which "was like a bridge to the 'action RPG', and Xanadu was taking those ideas to the next level." He also avoided implementing random encounters because he "always thought there was something weird about randomized battles, fighting enemies you can't see, whether you want to or not."[38]

Late 1980s

Another important influence on the action RPG genre was the 1986 action-adventure, The Legend of Zelda, which served as the template for many future action RPGs.[39] In contrast to previous action RPGs, such as Dragon Slayer and Hydlide, which required the player to bump into enemies in order to attack them, The Legend of Zelda featured an attack button that animates a sword swing or projectile attack on the screen.[14][24] It was also an early example of open-world, nonlinear gameplay, and introduced new features such as battery backup saving. These elements have been used in many action RPGs since.[40] The game was largely responsible for the surge of action-oriented RPGs released since the late 1980s, in Japan as well as in America, where it was often cited as an influence on action-oriented computer RPGs.[1]:182, 212[41] When it was released in North America, The Legend of Zelda was seen as a new kind of RPG with action-adventure elements, with Roe R. Adams (who worked on the Wizardry series) stating in 1990 that although "it still had many action-adventure features, it was definitely a CRPG" (computer role-playing game).[42] The popularity of the Legend of Zelda series prompted the creation of many new real-time action combat RPGs, and a decline in games featuring stat-heavy, turn-based combat.[3]:317 Despite its action-adventure genre, due to its similarities to previous action RPGs and its impact on the genre,[1]:216, 385 there continues to be much debate regarding whether or not The Legend of Zelda should be considered an action RPG.[1]:209–210 The Legend of Zelda series was classified as action-adventure for a long time, but as the genre expanded to include more RPG mechanics, The Legend of Zelda games were eventually recategorized as action RPGs.[11]

1986 also saw Namco releasing the arcade sequel to The Tower of Druaga, The Return of Ishtar,[43] an early action RPG[44] featuring two-player cooperative gameplay,[43] dual-stick control in single player, a female protagonist and the first heroic couple in gaming.[45] The same year, dB-SOFT's Woody Poco featured the ability to equip both a weapon and passive item (such as a lamp) at the same time, health regeneration based on food level, an in-game clock with day/night cycles and four seasons (along with daily/seasonal color changes), and the ability to gamble, steal, and bribe non-player characters.[13]

Other 1986 titles include Rygar and Deadly Towers, which were notable as some of the first Japanese console action RPGs to be released in North America, where they a new kind of RPG that differed from both the console action-adventures (such as Castlevania, Trojan, and Wizards & Warriors) and American computer RPGs (such as Wizardry, Ultima, and Might & Magic) that American gamers were more familiar with. Deadly Towers and Rygar were particularly notable for their permanent power-up mechanic, more similar to experience points used in other RPGs than typical action-adventure powerups.[10]

In 1987, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link implemented an RPG-esque system, including experience points and levels with action game elements,[46] making it closer to an action RPG than previous Zelda games.[47] Castlevania II: Simon's Quest, released in the same year, was an action RPG that combined the platform-action mechanics of the original Castlevania with the open-world of an action-adventure and RPG mechanics such as experience points.[48] It also introduced a persistent world with its own day-night cycle that affects when certain NPCs appear in certain locations and offered three possible multiple endings depending on the time it took to complete the game.[49]

Another Metroidvania-style open-world action RPG released that year was System Sacom's Sharp X1 computer game Euphory, which was possibly the only Metroidvania-style multiplayer action RPG produced, allowing two-player cooperative gameplay.[50] Other action RPG games released in 1987 include three Dragon Slayer titles, including Faxanadu, a side-scrolling spin-off of Xanadu,[18] and Dragon Slayer IV: Legacy of the Wizard, another early example of a non-linear open-world action RPG.[51] The fifth Dragon Slayer title, Sorcerian, was also released that year. It was a party-based action RPG, with the player controlling a party of four characters at the same time in a side-scrolling view. The game also featured character creation, highly customizable characters, class-based puzzles, and a new scenario system, allowing players to choose from 15 scenarios, or quests, to play through in the order of their choice. It was also an episodic video game, with expansion disks later released offering more scenarios.[14][52] Falcom also released the first installment of its Ys series in 1987. While not very popular in the West, the long-running Ys series has performed strongly in the Japanese market, with many sequels, remakes and ports in the decades that followed its release. Besides Falcom's own Dragon Slayer series, Ys was also influenced by Hydlide, from which it borrowed certain mechanics such as health-regeneration when standing still, a mechanic that has become common in video games today.[24][25] Ys was also a precursor to RPGs that emphasize storytelling,[53] and is known for its "bump attack" system, where the protagonist automatically attacks when running into enemies off-center, making level-grinding more swift and enjoyable.[54][26] The game also had what is considered to be one of the best and most influential video game music soundtracks of all time, composed by Yuzo Koshiro and Mieko Ishikawa.[54][55][56] In terms of the number of game releases, Ys is second only to Final Fantasy as the largest Eastern role-playing game franchise.[54]

Hydlide 3: The Space Memories was released for the MSX in 1987 and for the Sega Genesis as Super Hydlide in 1989. This game adopted the morality meter of its predecessor, expanded on its time mechanic with the introduction of an in-game clock setting day-night cycles and a need to sleep and eat, and made other additions such as cut scenes for the opening and ending, a combat system similar to that in The Legend of Zelda, the choice between four distinct character classes, a wider variety of equipment and spells, and a weight system affecting the player's movement depending on the overall weight of the equipment carried.[24] Another 1987 action RPG, The Magic of Scheherazade, was notable for several innovations: a unique setting based on the Arabian Nights, time travel between five different time periods, a unique combat system featuring both real-time solo action and turn-based team battles, and the introduction of team attacks where two party members could join forces to perform a more powerful attack.[57] That same year, Kogado Studio's sci-fi RPG Cosmic Soldier: Psychic War featured a unique "tug of war" style real-time combat system, where battles are a clash of energy between the party and the enemy, with the player needing to push the energy towards the enemy to strike them, while being able to use a shield to block or a suction ability to absorb the opponent's power. It also featured a new conversation system, where the player can recruit allies by talking to them, choose whether to kill or spare an enemy, and engage enemies in conversation, similar to Megami Tensei.[58] Wonder Boy in Monster Land combined the platform gameplay of the original Wonder Boy with many RPG elements,[59] which would inspire later action RPGs such as Popful Mail (1991).[60] The Faery Tale Adventure offered one of the largest worlds at the time, with over 17,000 computer screens without loading times.

In 1988, Telenet Japan's Exile series debuted, beginning with XZR: Idols of Apostate.[61] The series was controversial due to its plot, which revolves around a time-traveling Crusades-era Syrian assassin who assassinates various religious/historical figures as well as 20th century political leaders,[62] similar to the present-day Assassin's Creed action game series.[63] The gameplay of Exile included both overhead exploration and side-scrolling combat, and featured a heart monitor to represent the player's Attack Power and Armor Class statistics. Another controversial aspect of the game involved taking drugs (instead of potions) that increase/decrease attributes, but with side effects such as heart-rate increase/decrease or death.[62] Origin Systems, the developer of the Ultima series, also released an action RPG in 1988, titled Times of Lore, which was inspired by various NES titles, particularly The Legend of Zelda.[1]:182, 212 Times of Lore inspired several later titles by Origin Systems, such as the 1990 games Bad Blood (another action RPG based on the same engine)[1] and Ultima VI: The False Prophet, based on the same interface.[64] In 1988, World Court Tennis for the TurboGrafx-16 introduced a new form of gameplay: a tennis-themed sports RPG mode.[65]

In 1989, Sega released a Metroidvania-style open-world action RPG for the Master System console, Wonder Boy III: The Dragon's Trap.[50] Dungeon Explorer, developed by Atlus and published by Hudson Soft for the TurboGrafx-16 in 1989, featured cooperative multiplayer gameplay allowing up to five players to play simultaneously.[66][67] The same year, River City Ransom featured elements of both the beat 'em up and action RPG genres, combining brawler combat with many RPG elements, including having an inventory, buying and selling items, learning new abilities and skills, listening for clues, searching to find all the bosses, shopping in the malls, buying items to heal, and increasing stats.[68] It was also an early sandbox brawler, similar to the Grand Theft Auto series.[69] Also in 1989, the enhanced remake Ys I & II was one of the first video games to use CD-ROM, which was utilized to provide enhanced graphics, animated cut scenes,[70][26] a Red Book CD soundtrack,[71][26] and voice acting.[70][71] Its English localization was also one of the first to use voice dubbing. The game received the Game of the Year award from OMNI Magazine in 1990, as well as other prizes.[70] Another 1989 release, Activision's Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon, attempted to introduce "Nintendo-style" action combat to North American computer role-playing games.[72]

Early–mid-1990s

1990 featured the release of Crystalis for the NES as well as Golden Axe Warrior for the Sega Master System. These games featured Zelda-like gameplay along with RPG elements such as experience points, statistics-based equipment, and a magic-casting system. Crystalis also featured a post-apocalyptic setting inspired by Hayao Miyazaki's Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, and in turn influenced the game Secret of Mana.[73] Data East's Gate of Doom was an arcade action RPG that combined beat 'em up fighting gameplay with fantasy role-playing and introduced an isometric perspective.[74] Enix released a unique biological simulation action RPG by Almanic that revolved around the theme of evolution, 46 Okunen Monogatari, a revised version of which was released in 1992 as E.V.O.: Search for Eden.[75]

In 1991, Square released Seiken Densetsu: Final Fantasy Gaiden, also known as Final Fantasy Adventure or Mystic Quest in the West, for the Game Boy. Like Crystalis, the action in Seiken Densetsu bore a strong resemblance to that of Legend of Zelda, but added more RPG elements. It was one of the first action RPGs to allow players to kill townspeople, though later Mana games removed this feature.[76] That same year, the erotic adult RPG Dragon Knight III, released for the PC-8801 and as Knights of Xentar for MS-DOS, introduced a unique pausable real-time battle system,[77][78] where characters automatically attack based on a list of different AI scripts,[78] though this meant that the player had no control over the characters during battle other than to give commands for spells, item use, and AI routines.[77] Arcus Odyssey by Wolf Team (now Namco Tales Studio) was an action RPG that featured an isometric perspective and co-operative multiplayer gameplay.[79] In 1992, Sega released the Climax Entertainment game Landstalker: The Treasures of King Nole, an early isometric RPG that combined the gameplay of an open-world action RPG with an isometric platformer, alongside an emphasis on varied puzzle-solving as well as strong characters and humorous conversations.[80]

In 1993, the second Seiken Densetsu game, Secret of Mana, received considerable acclaim,[81] for its innovative pausable real-time action battle system,[82][83] modified Active Time Battle meter adapted for real-time action as a stamina bar,[1][84] the "Ring Command" menu system where a variety of actions can be performed without needing to switch screens,[82] its innovative cooperative multiplayer gameplay[81] (where the second or third players could drop in and out of the game at any time, rather than players having to join the game at the same time),[85] and the customizable AI settings for computer-controlled allies.[86] Edge magazine in 1993 praised it as "a class of its own as far as action RPGs or adventures go."[87] The game has remained influential through to the present day, with its ring menu system still used in modern games and its cooperative multiplayer mentioned as an influence on games such as Dungeon Siege III (2011).[85] Other action RPGs at the time combined the puzzle-oriented action-adventure gameplay style of the Legend of Zelda series with RPG elements. Examples include Illusion of Gaia (1993) and its successor Terranigma (1995), as well as Alundra (1997), a spiritual successor to LandStalker.

Arcade hack and slash RPGs created in the 1990s blended together beat 'em up and RPG characteristics. An early example was Alpha Denshi's 1990 game Crossed Swords, which combined the first-person brawler gameplay of The Super Spy (released the same year) with RPG elements, while replacing the shooting with hack and slash combat.[88] Most other such games, however, used a side-scrolling perspective typical of beat 'em ups, such as Capcom's Knights of the Round (1991), King of Dragons (1991), Dungeons & Dragons: Tower of Doom (1993) and Dungeons & Dragons: Shadow over Mystara (1996); these games were released for the arcades and later released for the Sega Saturn together as the Dungeons & Dragons Collection (1999). Several other beat 'em ups followed a similar hack and slash brawler-RPG formula, including Guardian Heroes, Castle Crashers, Dungeon & Fighter, and the Princess Crown series (including Odin Sphere and Muramasa: The Demon Blade).

Around this time, some within the American computer RPG community argued that cartridge-based Japanese console action RPGs "are not role-playing at all" due to many of the popular examples back then, such as Secret of Mana and especially The Legend of Zelda, using "direct" arcade-style action combat systems instead of the more "abstract" turn-based battle systems associated with table-top RPGs and American computer RPGs of that era. In response, game designer Sandy Petersen noted that not all console RPGs are action-based, pointing to Final Fantasy and Lufia, and that some computer RPGs such as Ultima VIII have also begun following the console trend of adopting arcade action elements.[89]

Late 1990s–present

Tales of Phantasia was released in Japan for the Super Famicom in 1995, featuring a real-time side-scrolling fighting game-influenced combat mode and an exploration mode similar to classic console RPGs. In 1996, Star Ocean was released with similar real-time combat and classic exploration, but featuring a more isometric view during battle. Star Ocean also introduced a "private actions" system, where the player can affect the relationships between characters, which in turn affects the plot and leads to multiple endings, a feature that the Star Ocean series later became known for.[90] Namco and Enix did not publish these two titles in America, though many of their sequels were later released in the U.S., beginning with Tales of Destiny and Star Ocean: The Second Story. LandStalker's 1997 spiritual successor Alundra[91] is considered "one of the finest examples of action/RPG gaming," combining platforming elements and challenging puzzles with an innovative storyline revolving around entering people's dreams and dealing with mature themes.[92]

The fifth generation era of consoles saw a number of other popular action RPGs, such as King's Field, Brave Fencer Musashi, The Legend of Oasis, Tail of the Sun, Dragon Valor, and Tales of Eternia. A number of action RPGs were produced for sixth generation consoles, such as Phantasy Star Online, Dark Cloud & Dark Chronicle (also released as Dark Cloud 2), Sudeki, King's Field IV & Shadow Tower Abyss, Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance, Champions of Norrath, Kingdom Hearts, Chaos Legion, .hack, Monster Hunter, World of Mana, Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles & Crisis Core: Final Fantasy VII, Rogue Galaxy, Odin Sphere, Souls series, Drakengard, Bloodborne, Nier: Automata and several Tales games such as Symphonia.

Other subgenres

First-person dungeon crawl

The majority of first-person computer games up until the late 1980s were turn-based, though a few had attempted to incorporate real-time elements, such as Dungeons of Daggorath and the 1985 game Alternate Reality: The City. The Bard's Tale, released in 1985, attempted to generate random encounters when the player was away from the keyboard to give the impression that monsters were constantly moving. In late 1987, FTL Games released Dungeon Master, a dungeon crawler that had a real-time game world and some real-time combat elements (akin to Active Time Battle), requiring players to quickly issue orders to the characters, setting the standard for first-person computer RPGs for several years.[1]:234–236 Other first-person RPGs in the style of Dungeon Master include SSI's Eye of the Beholder (1990) and Raven Software's Black Crypt (1992).

Arsys Software released Star Cruiser for the NEC PC-8801 computer in early 1988. The game is notable for being a very early example of an action RPG with fully 3D polygonal graphics[93] combined with first-person shooter gameplay.[94] It was later ported to the Sega Mega Drive in 1990.[94] Also in 1988, Alpha Denshi's Crossed Swords for the arcades combined the first-person beat 'em up gameplay of SNK's The Super Spy (released the same year) with RPG elements, while replacing the first-person shooting with hack and slash combat.[88] The 1989 title Dragon Wars was a first-person computer RPG influenced by console titles such as The Legend of Zelda.[41]

In 1992, Blue Sky Productions released Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss, a technologically advanced game due to its 3D first-person ray casting graphics combined with real-time action and a surprisingly deep role-playing experience. One of the game's developers, Warren Spector, would go on to help develop more games combining first-person action and RPG gameplay, such as System Shock and Deus Ex.

Other first-person RPGs in the style of Ultima Underworld include Shadowcaster by Raven Software and id Software in 1993 (created with an early version of the Doom engine), The Elder Scrolls series and Fallout 3 by Bethesda, Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines by Troika Games, Baroque by Sting Entertainment and Hellgate: London by Flagship Studios, which was formed from Blizzard North executives and developers responsible for the Diablo franchise, which also supports third-person view. FromSoftware's King's Field series of dungeon-crawler action RPGs used a fully 3D polygonal first-person perspective from 1994 to 2001, though the series' 2009 spiritual successor Demon's Souls had adopted a third-person view instead.

In 2012, game developer Almost Human released Legend of Grimrock, and the sequel Legend of Grimrock II in 2014. Both games are throwbacks to the older dungeon crawler games, but with modern 3D graphics and real-time combat. A sequel to the long-running franchise Might and Magic was also released in 2014, Might & Magic X: Legacy, maintaining the older tradition of turn-based combat.

Point and click

Action RPGs were far more common on consoles than computers, due to gamepads being better suited to real-time action than the keyboard and mouse.[3]:43 Though there were attempts at creating action-oriented computer RPGs during the late 1980s and early 1990s, very few saw any success.[3]:43 Times of Lore was one of the more successful attempts in the American computer market,[3]:43 where there was a generally negative attitude towards combining genres in this way and more of an emphasis on preserving the purity of the RPG genre.[11] For example, a 1991 issue of Computer Gaming World criticized several computer role-playing games for using "arcade" or "Nintendo-style" action combat, including Ys, Sorcerian, Times of Lore, and Prophecy.[72]

An early attempt at incorporating a point-and-click interface into a real-time overhead action RPG was Silver Ghost,[95] a 1988 NEC PC-8801 game by Kure Software Koubou.[96] It was a tactical action RPG where characters could be controlled using a cursor.[95] A similar game released by Kure Software Koubou the same year was First Queen, a hybrid between real-time strategy, action RPG, and strategy RPG. Like an RPG, the player can explore the world, purchase items, and level up, and like a strategy video game, it focuses on recruiting soldiers and fighting against large armies rather than small parties. The game's "Gochyakyara" ("Multiple Characters") system lets the player control one character at a time while the others are controlled by computer AI that follow the leader, and allows battles to be large-scale.[97][98] Another early overhead action RPG that used mouse controls was Nihon Falcom's 1991 game Brandish, where the player could move forward, backward, turn, strafe and attack by clicking on boxes surrounding the player character.[99]

The 1988 Origin Systems title Times of Lore was an action RPG with an icon-based point-and-click interface.[100] The game's design and interface was inspired by console titles, particularly The Legend of Zelda, which influenced the game's accessible interface, real-time gameplay, and constant-scale open world (rather than an unscaled overworld).[41] In turn, these console-influenced elements and the point-and-click interface were adopted by later Origin Systems titles, including Bad Blood,[1][41] Ultima VI,[100][41] and Ultima VII.[3]:347 Times of Lore was a precursor to Diablo and Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance.[101]

The 1994 title Ultima VIII used mouse controls and attempted to add precision jumping sequences reminiscent of a Mario platform game, though reactions to the game's mouse-based combat were mixed. It was not until 1996 that a stagnant PC RPG market was revitalized by Blizzard's Diablo, an action RPG that used a point-and-click interface and offered gamers a free online service to play with others that maintained the same rules and gameplay.[3]:43

Diablo's effect on the market was significant, inspiring many imitators. Its impact was such that the term "action RPG" has come to be more commonly used for Diablo-style games rather than Zelda-style games, with The Legend of Zelda itself recategorized as an action-adventure.[11] Diablo's style of combat eventually went on to be used by many massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) developed in the years after Diablo's release. For many years afterwards, games that closely mimicked the Diablo formula were referred to as "Diablo clones". The definition of a Diablo clone is even vaguer than that of an action RPG, but typically such games have each player controlling a single character and have a strong focus on combat, with plot and character interaction kept to a minimum. Non-player characters (NPCs) are often limited in scope. For example, an NPC could be either a merchant who buys and sells items, or a service provider who upgrades the player's skills, resources, or abilities. Diablo clones are also considered to have few or no puzzles to solve because many problems instead have an action-based solution (such as breaking a wooden door open with an axe rather than having to find its key).

Blizzard later released a sequel, Diablo II in 2000, which became popular in America, Europe, and Asia. Diablo II's effect on the gaming industry led to an even larger number of "clones" than its predecessor, inspiring games for almost a decade. Diablo III was released on May 15th, 2012. Some of the aforementioned Diablo "clones" are: the Sacred series, Titan Quest, Dungeon Siege series, Darkstone: Evil Reigns, Loki: Heroes of Mythology, Legend: Hand of God, Fate, Torchlight, Path of Exile, The Incredible Adventures of Van Helsing, Marvel Heroes 2015, and Grim Dawn.

Role-playing shooter

Role-playing shooters (often abbreviated RPS) are sometimes considered a subgenre, featuring elements of both shooter games and action RPGs.[102] An early example was Magical Zoo's The Screamer,[36] a 1985 post-apocalyptic sci-fi RPG released in Japan for the NEC PC-8801 computer, set after World War III and revolving around cyberpunk and biological horror themes.[34][35] The gameplay switched between first-person dungeon crawl exploration and side-scrolling shooter combat, where the player could jump, duck and shoot at enemies in real-time.[36] Also released in 1985, Dragon Slayer II: Xanadu allowed the player to shoot projectile magic attacks at enemies.[18] The earliest to feature 3D polygonal graphics was the 1986 game WiBArm, released by Arsys Software for the NEC PC-88 computer in Japan and ported to MS-DOS for Western release by Brøderbund. In WiBArm, the player controls a transformable mecha robot, switching between a 2D side-scrolling view during outdoor exploration to a fully 3D polygonal third-person perspective inside buildings, while bosses are fought in an arena-style 2D shoot 'em up battle. The game featured a variety of weapons and equipment as well as an automap, and the player could upgrade equipment and earn experience to raise stats.[50][103] In contrast to first-person RPGs at the time that were restricted to 90-degree movements, WiBArm's use of 3D polygons allowed full 360-degree movement.[103]

In 1987, Shiryou Sensen: War of the Dead, an MSX2 title developed by Fun Factory and published by Victor Music Industries, was the first true survival horror RPG.[104][105] Designed by Katsuya Iwamoto, the game revolved around a female SWAT member, Lila, rescuing survivors in an isolated monster-infested town and bringing them to safety in a church. It was open-ended like Dragon Quest and had real-time side-view battles like Zelda II. Unlike other RPGs at the time, however, the game had a dark and creepy atmosphere expressed through the story, graphics, and music,[104] while the gameplay used shooter-based combat and gave limited ammunition for each weapon, forcing the player to search for ammo and often run away from monsters in order to conserve ammo.[105]

Released in 1988, The Scheme, released by Bothtec for the PC-8801, was an action RPG with a similar side-scrolling open-world gameplay to Metroid.[50] Compile's The Guardian Legend that year was a successful fusion of the action-adventure, shoot 'em up and role-playing game genres, later inspiring acclaimed titles such as Sigma Star Saga in 2005.[106] Also in 1988, Arsys Software released Star Cruiser for the PC-88. The game is notable for being a very early example of an RPG with fully 3D polygonal graphics,[93] combined with first-person shooter gameplay,[94] which would occasionally switch to space flight simulator gameplay when exploring outer space with six degrees of freedom. All the backgrounds, objects and opponents in the game were rendered in 3D polygons, many years before they were widely adopted by the gaming industry. The game also emphasized storytelling, with plot twists and extensive character dialogues.[93] It was later ported to the Sega Mega Drive in 1990.[94] The game's sequel, Star Cruiser 2, was released in 1992,[107] for the PC-9821 and FM Towns computers.[108]

In 1990, Hideo Kojima's SD Snatcher, while turn-based, introduced a new first-person shooter-based battle system where firearm weapons (each with different abilities and target ranges) have limited ammunition and the player can aim at specific parts of the enemy's body with each part weakening the enemy in different ways. Such a battle system has rarely been used since,[109] though similar battle systems based on targeting individual body parts can be found in Square's Vagrant Story (2000), a pausable real-time RPG[110] that uses both melee and bow and arrow weapons,[111] as well as Bethesda's Fallout 3 (2008) and Nippon Ichi's Last Rebellion (2010).[112] In 1996, Night Slave was a shooter RPG released for the PC-98 that combined the side-scrolling shooter gameplay of Assault Suits Valken and Gradius (including an armaments system that employs recoil physics) with many RPG elements, such as permanently levelling up the mecha and various weapons using power-orbs obtained from defeating enemies, as well as storyline cut scenes, which occasionally feature erotic lesbian adult content.[50]

Other early shooter-based action RPGs include the Parasite Eve series of survival horror RPGs (1998 onwards) by Square (now Square Enix),[113][114] the Deus Ex series (2000 onwards) by Ion Storm, Ancient's vehicular combat RPG Car Battler Joe (2002),[115] Konami's solar-powered stealth-based Boktai series (2003 onwards),[116] Irem's Steambot Chronicles (2005),[117] Square Enix's third-person shooter RPG Dirge of Cerberus: Final Fantasy VII (2006), which introduced an over-the-shoulder perspective similar to Resident Evil 4,[118] and the MMO vehicular combat game Auto Assault (2006) by NetDevil and NCsoft.[115] Other action RPGs featured both hack and slash and shooting elements, with the use of both guns (or in some cases, bow and arrow or aerial combat) and melee weapons, including the Shin Megami Tensei: Devil Summoner series (1995 onwards) by Atlus,[119] tri-Ace's Star Ocean series (1996 onwards),[120][121] Cavia's flight-based Drakengard series (2003 to 2005),[122] and Level-5's Rogue Galaxy (2005).[123]

Other RPS games include the Mass Effect series (2007 onwards), Fallout 3 (2008), White Gold: War in Paradise (2008), and Borderlands (2009).[102] Borderlands developer Gearbox software has dubbed it as a "role-playing shooter" due to the heavy RPG elements within the game, such as quest-based gameplay and also its character traits and leveling system.[124] Sega's Valkyria Chronicles series (2008 onwards) features a mixture of tactical role-playing game, real-time strategy and third-person tactical shooter elements (including a cover system), for which it has been described as "the missing link" between Final Fantasy Tactics and Full Spectrum Warrior.[125] Half-Minute Hero (2009) is an RPG shooter featuring self-referential humour and a 30-second time limit for each level and boss encounter.[126] Other recent action role-playing games with shooter elements include the 2010 titles Resonance of Fate by tri-Ace,[127] Alpha Protocol by Obsidian Entertainment, and The Last Story by Mistwalker which uses crossbows (instead of guns) in a manner similar to cover-based third-person shooters.[128] Square Enix's 2010 release, The 3rd Birthday, the third game in the Parasite Eve series, features a unique blend of action RPG, real-time tactical RPG, survival horror and third-person tactical shooter elements.[129][130] The 2010 cult hit NIER is a multi-genre action-RPG with a heavy emphasis on 2D and 3D bullet hell game mechanics. Knights in the Nightmare is an RPG with real-time strategy/bullet hell gameplay.

More recent shooter-based RPGs include Imageepoch's post-apocapytic Black Rock Shooter (2011), which employs both first-person and third-person shooter elements;[131][132] Square Enix's Final Fantasy XV (2016), which features both hack and slash and third-person shooter elements;[133] and Final Fantasy Type-0 (2011), which plays similarly to The 3rd Birthday, but is not limited to shooting.[134]

Choices and consequences

While most action RPGs focus on hack and slash gameplay while exploring a world (often an open-world) and building character stats, some non-linear titles contain events or dialogue choices with consequences in the game world or storyline. The concept of moral consequences and alignments can be seen in action RPGs as early as the 1985 releases Dragon Slayer II: Xanadu, with its Karma system where the character's Karma meter will change depending on whom he kills (which in turn affects the way other NPCs react to him),[30] and Hydlide II: Shine of Darkness, where the player can be aligned with Justice, Normal, or Evil, depending on whether the player kills good or evil monsters or humans, leading to townsfolk ignoring players with an evil alignment.[24]

Woody Poco, released in 1986, allowed the player to make choices, such as gambling, bribing, and stealing, with consequences for the player's actions.[13] Cosmic Soldier: Psychic War (1987) featured a non-linear conversation system, where the player could recruit allies by talking to them, choose whether to kill or spare an enemy, and engage enemies in conversation, similar to Megami Tensei.[58] One of the first action RPGs to feature multiple endings was Konami's 1987 release Castlevania II: Simon's Quest, which introduced a day-night cycle which affects when certain NPCs appear in certain locations, and offers three possible endings depending on the time it takes to complete the game.[49] In 1988, Ys II introduced the ability to transform into a monster, which allows the player to both scare human non-player characters, prompting unique dialogues, as well as interact with monsters. This is a recurring feature in the series, offering the player insight into the enemies to an extent that very few other games allow to this day.[54]

Some of Quintet's action RPGs allowed players to shape the world through town-building simulation elements, such as Soul Blazer in 1992 and Terranigma in 1995.[135] That same year, Square's Seiken Densetsu 3 allowed a number of different possible storyline paths and endings depending on which combination of characters the player selected. The game also introduced a class-change system incorporating light-dark alignments.[136][137] The following year, Treasure's Guardian Heroes allowed players to alter the storyline through their actions, such as choosing between a number of branching paths leading to multiple different endings and through the Karma meter which changes depending on whether the player kills civilians or shows mercy to enemies.[138][139]

Some of the earliest action RPGs to allow players to alter the storyline's outcome through dialogue choices were tri-Ace's Star Ocean series of sci-fi RPGs. The original Star Ocean, published by Enix in 1996, introduced a "private actions" social system. The protagonist's relationship points with the other characters are affected by the player's choices, which in turn affects the storyline, leading to branching paths and multiple different endings.[90][140] This was expanded in its 1999 sequel, Star Ocean: The Second Story, which included 86 different endings.[141] Using a relationship system inspired by dating sims, each of the characters had friendship points and relationship points with each of the other characters, allowing the player to pair together characters of their choice both romantically and platonically, allowing a form of fan fiction to exist within the game itself. This type of social system was later extended to allow romantic relationships in BioWare's 2007 sci-fi RPG Mass Effect. However, the relationship system in Star Ocean not only affected the storyline, but also the gameplay, affecting the way the characters behave towards each other in battle.[142]

In 1997, Quintet's game The Granstream Saga, while having a mostly linear plot, offered a difficult moral choice towards the end of the game regarding which of two characters to save, with each choice leading to a different ending.[143] In 1999, Square's Legend of Mana,[144] the most open-ended game in the Mana series,[145] allowed the player to build the game world however they choose, complete any quests and subplots in any order of their choice, and select which storyline paths to follow,[144][146] departing from most other action RPGs of the time.[147] In the same year, Square's survival horror RPG Parasite Eve II featured branching storylines and up to three different possible endings.[148]

Another example of choices and consequences in the RPG genre is the Deus Ex series, which debuted in 2000. Inspired by the limited choices in Suikoden (1995), Warren Spector expanded on the idea with more meaningful choices in Deus Ex.[149]

Many other games allow the player to make game-altering choices in dialogues and events, while still maintaining their respective action elements, whether they be in the first person or the third person. Such games include Chrono Trigger (1995), Orphen: Scion of Sorcery (2000), Gothic (2001), Gothic II (2002), Tales of Symphonia (2003), Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines (2004), Radiata Stories (2005), Steambot Chronicles (2005), Gothic 3 (2006), The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006), Odin Sphere (2007), Fallout 3 (2008), White Gold: War in Paradise (2008), Infinite Space (2009), Alpha Protocol (2010), Dragon's Dogma (2012), and the Way of the Samurai, Drakengard, Fable, Yakuza, Devil Summoner, Mass Effect and The Witcher video games.

Criticism

Jordane Thiboust of Beenox criticized the term "action role-playing game", stating that it does not represent what core experience the game offers to the player. He claimed that "[action role-playing game] is not a real subgenre" but "the current marketing slang for [...] '[role-playing video games] that are cool to play with a pad'", so that as more and more role-playing games are marketed as "action role-playing games", the label becomes increasingly useless. He also pointed out the danger of creating false consumer expectations, as "action role-playing game" largely describes the type of combat to expect in a game, however says nothing about the overall player experience (narrative, sandbox, or dungeon crawl) it has to offer.[150]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Barton, Matt (2008). Dungeons & Desktops: The History of Computer Role-Playing Games. Wellesley, Massachusetts: A K Peters. ISBN 1568814119.

- ↑ Dungeons of Daggorath at MobyGames

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (2009). Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the Most Influential Games of All Time. Boston: Focal Press. ISBN 0240811461.

- ↑ "Bokosuka Wars". GameSpot. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ↑ Bokosuka Wars at AllGame

- ↑ "Gems In The Rough: Yesterday's Concepts Mined For Today". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 "VC ボコスカウォーズ". Nintendo.co.jp. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Dru Hill: The Chronicle of Druaga". 1up.com. 2004-10-25. Archived from the original on 2005-01-19. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 "Hardcore Gaming 101 – Blog: Dark Age of JRPGs (7): Panorama Toh ぱのらま島 – PC-88 (1983)". Hardcore Gaming 101. 2013-06-02. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 Adams, Roe R. (November 1990), "Westward Ho! (Toward Japan, That Is): An Overview of the Evolution of CRPGs on Dedicated Game Machines", Computer Gaming World (76), pp. 83–84,

While America has been concentrating on yet another Wizardry, Ultima, or Might & Magic, each bigger and more complex than the one before it, the Japanese have slowly carved out a completely new niche in the realm of CRPG. The first CRPG entries were Rygar and Deadly Towers on the NES. These differed considerably from the "action adventure" games that had drawn quite a following on the machines beforehand. Action adventures were basically arcade games done in a fantasy setting such as Castlevania, Trojan, and Wizards & Warriors. The new CRPGs had some of the trappings of regular CRPGs. The character could get stronger over time and gain extras which were not merely a result of a short-term "Power-Up." There were specific items that could be acquired which boosted fighting or defense on a permanent basis. Primitive stores were introduced with the concept that a player could buy something to aid him on his journey.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jeremy Parish (2012). "What Happened to the Action RPG?". 1UP. Archived from the original on 2015-01-12. Retrieved 2015-01-14.

- ↑ "Felipe Pepe's Blog – 1982–1987 – The Birth of Japanese RPGs, re-told in 15 Games". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Szczepaniak, John (2015). The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Volume 2. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781518818745.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kalata, Kurt. "Dragon Slayer". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 3 Shigeaki, Kamada (2007). "レトロゲーム配信サイトと配信タイトルのピックアップ紹介記事「懐かし (Retro)". 4Gamer.net. Retrieved 2011-05-19. (Translation)

- ↑ Falcom Chronicle, Nihon Falcom

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Falcom Classics". GameSetWatch. July 12, 2006. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kalata, Kurt. "Xanadu". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- 1 2 "History of Japanese Video Games | Kinephanos". Kinephanos.ca. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 3 Posted by derboo (2014-05-26). "Hardcore Gaming 101 – Blog: Dark Age of JRPGs (10): Courageous Perseus". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Hydlide (PC88)". Famitsu. Retrieved 2015-01-14.

- ↑ Hideo Kojima (May 25, 2014). "Hideo Kojima Tweet". Twitter.

- ↑ Doke, Shunal (2015-11-03). "IGN India discusses game design: Combat in open world games – IGNdia". In.ign.com. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kalata, Kurt; Greene, Robert. "Hydlide". Hardcore Gaming 101.

- 1 2 Szczepaniak, John (7 July 2011). "Falcom: Legacy of Ys". GamesTM (111): 152–159 [153]. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- 1 2 3 4 Szczepaniak, John (July 8, 2011). "History of Ys interviews". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 6 September 2011.)

- ↑ Dragon Buster at the Killer List of Videogames

- ↑ By Zergnet. "Gaming's most important evolutions | GamesRadar". Gamesradar.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Buster Action role-playing game at AllGame

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Xanadu Next home page". Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-08. (Translation)

- ↑ Jeremy Parish. "Metroidvania". GameSpite.net. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ↑ Jeremy Parish (August 18, 2009). "8-Bit Cafe: The Shadow Complex Origin Story". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ↑ Hydlide II: Shine of Darkness at MobyGames

- 1 2 "The Screamer". 4Gamer.net. 2006-12-26. Retrieved 2011-03-29. (Translation)

- 1 2 "The Screamer Fiche RPG (reviews, previews, wallpapers, videos, covers, screenshots, faq, walkthrough) – Legendra RPG". Legendra.com. 1985-05-25. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 3 4 The Screamer at MobyGames

- ↑ "Game Design Essentials: 20 RPGs". Gamasutra. 2009-07-02. Archived from the original on 2011-10-12. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- ↑ "shmuplations.com". shmuplations.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "GameSpy's 30 Most Influential People in Gaming". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- ↑ "15 Most Influential Games of All Time: The Legend of Zelda". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2010-05-15. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Computer Gaming World, issue 68 (February 1990), pages 34 & 38

- ↑ Adams, Roe R. (November 1990), "Westward Ho! (Toward Japan, That Is): An Overview of the Evolution of CRPGs on Dedicated Game Machines", Computer Gaming World (76), pp. 83–84 [83],

When The Legend of Zelda burst upon the scene in fall of 1988, it hit like a nova. Although it still had many action-adventure features, it was definitely a CRPG.

- 1 2 The Return of Ishtar at the Killer List of Videogames

- ↑ "The Return of Ishtar Release Information for FM-7". GameFAQs. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Dru Hill: The Chronicle of Druaga". 1up.com. 2004-10-25. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Comedy (2006-02-25). "Zelda II: The 20-Year-Late Review". WIRED. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Classic NES Series: Zelda II (Game Boy Advance) Overview – CNET". Reviews.cnet.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "25. Castlevania II: Simon's Quest – Top 100 NES Games". IGN. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 Mike Whalen, Giancarlo Varanini. "The History of Castlevania – Castlevania II: Simon's Quest". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 John Szczepaniak. "Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier". Hardcore Gaming 101. p. 4. Retrieved 2011-03-18. (Reprinted from Retro Gamer, Issue 67, 2009)

- ↑ Harris, John (September 26, 2007). "Game Design Essentials: 20 Open World Games". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ "Sorcerian (PC) – GameCola". Gamecola.net. 2010-10-30. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Ys Series". Nihon Falcom. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Szczepaniak, John (7 July 2011). "Falcom: Legacy of Ys". GamesTM (111): 152–159 [154]. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

- ↑ Kalata, Kurt (27 November 2010). "Ys". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ↑ Chris Greening & Don Kotowski (February 2011). "Interview with Yuzo Koshiro". Square Enix Music Online. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ↑

- 1 2

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2 3

- 1 2

- 1 2

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ (Reprinted from Retro Gamer, Issue 67, 2009)

- ↑

- 1 2

- 1 2

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2

- 1 2

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2 Crossed Swords at AllGame

- ↑ Petersen, Sandy (August 1994). "Eye of the Monitor". Dragon (208): 61.

Not long ago, I received a letter from a DRAGON® Magazine reader. This particular woman attacked the whole concept of cartridge-based role-playing games very vigorously, claiming that games such as Zelda are not role-playing at all. Presumably, she thinks they are arcade games. Zelda has some features of the classic arcade game: combat is direct. Each push of the button results in one swing of the sword, which if it connects, harms or kills an enemy. In standard computer roleplaying games, at least until recently, combat is more abstract. [...] But all that is changing. [...] Ultima VIII requires you not only to control your character's every move in combat, but also his dodging of enemy blows, whether he kicks or stabs, etc. [...] The two forms of play: "arcade" and "role-playing" seem to be mixing more and more in computer and cartridge games. We'll see how far this trend goes, but I suspect there will always be a place for a game which is totally cerebral in combat, instead of relying on reflexes. For every Zelda, or Secret of Mana, there'll be a Final Fantasy II or Lufia.

- 1 2 Lada, Jenni (February 1, 2008). "Important Importables: Best SNES role-playing games". Gamer Tell. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- ↑ Webber (2 March 1998). "Alundra". RPGFan. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Conrad (2009-03-20). "An RPG Draws Near! Alundra". Destructoid. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 スタークルーザー (translation), 4Gamer.net

- 1 2 3 4 Star Cruiser at AllGame

- 1 2 Kurt Kalata (February 4, 2010). "So What the Heck is Silver Ghost". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- ↑ Silver Ghost (Translation), Kure Software Koubou

- ↑ "Official Site". Kure Software Koubou. Retrieved 2011-05-19. (Translation)

- ↑ First Queen at MobyGames

- ↑ Kurt Kalata. "Brandish". Hardcore Gaming 1010. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- 1 2 "The Official Book Of Ultima". Archive.org. 2010-07-21. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- ↑ "Lemon – Commodore 64, C64 Games, Reviews & Music!". Lemon64.com. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- 1 2 "A Visual Guide To The Role-Playing Game". Kotaku.com. 2010-05-25. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- 1 2 "【リリース】プロジェクトEGGから3月25日に「ウィバーン」発売". 4Gamer.net. Retrieved 2011-03-05. (Translation)

- 1 2 "The PC Engine] Shiryō Sensen @ Magweasel". Magweasel.com. 2009-11-10. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 Szczepaniak, John (2011-01-15). "War of the Dead". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Thomas, Lucas M. (2005-08-18). "Game Time: 'Sigma Star Saga'". Evansville Courier & Press. p. D11. Archived from the original on 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20040201144907/http://dengeki.jp/~roburi/cd.csv

- ↑ 日記(バックナンバー) (Translation), Dengeki

- ↑ Kalata, Kurt (2009-09-19). "Snatcher". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Jeremy Parish (2006-03-18). "Retronauts: Volume 4 – Yasumi Matsuno". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ↑ "Vagrant Story – Retroview". RPGamer. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ↑ European date fixed for the action / RPG Last Rebellion (Translation), Jeuxvideo.com

- ↑ Larry, Scary (2010-01-03). "Parasite Eve Review from GamePro". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2010-01-03. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Sean Ridgeley (March 15, 2011). "Parasite Eve released on PlayStation Network". Neoseeker. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- 1 2 Kaiser, Joe (July 8, 2005). "Unsung Inventors". Next-Gen.biz. Archived from the original on 2005-10-28. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ "Retro/Active: Metal Gear from". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ By Spencer . May 23, 2006 . 3:58pm (2006-05-23). "Steambot Chronicles". Siliconera. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Dirge of Cerberus: Final Fantasy VII". Siliconera. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ↑ By Spencer . October 11, 2006 . 4:00am (2006-10-11). "Shin Megami Tensei: Devil Summoner – Raidou Kuzunoha vs. The Soulless Army". Siliconera. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ↑ Herring, Will (2009-10-29). "Star Ocean: Second Evolution Review from GamePro". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Reynolds, Matthew (2010-01-18). "Preview: 'Resonance of Fate' (360, PS3)". Digitalspy.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Drakengard Preview for PS2 from". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Yang, Louise (2007-01-26). "Rogue Galaxy: charming and cel shaded". Siliconera. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Inside Mac Games Review: Borderlands: Game Of The Year Edition". Insidemacgames.com. 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "IGN: Valkyria Chronicles Review". IGN. October 29, 2008. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ↑ Keith Stuart (4 March 2011). "2D Forever: the fall and rise of hardcore Japanese game design". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ↑ Orry, James (2010-02-11). "Resonance of Fate out March 26 – Resonance of Fate for Xbox 360 News". Videogamer.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Tom Goldman (2010-07-09). "Trailer: Sakaguchi's Last Story a Wii RPG To Anticipate | The Escapist". Escapistmagazine.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Patrick Kolan (March 25, 2011). "The 3rd Birthday Review: Manhattan just can't catch a break these days". IGN. Retrieved 2011-04-01.

- ↑ David Wolinsky (April 7, 2011). "The 3rd Birthday review: New year's Eve". Joystiq. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ↑ Tom Goldman (2010-11-24). "Imageepoch Unveils New Wave of JRPGs | The Escapist". Escapistmagazine.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Spencer (2010-11-23). "Black Rock Shooter: The Game In Development For PSP [Update: Trailer". Siliconera. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Final Fantasy Versus XIII trailer leaks out – GamerTell | TechnologyTell". GamerTell. 2011-01-18. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy (2011-09-14). "TGS: Final Fantasy Type-0 is Dark, Ambitious, Promising (PSP): The game formerly known as Agito demos well on the show floor". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ↑ by David DeRienzo – February 27, 2007 (2007-02-27). "Quintet Heaven and Earth Trilogy". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "RPGFan Reviews – Seiken Densetsu 3". Rpgfan.com. 1995-09-30. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Reviews: Seiken Densetsu 3". 1UP.com. 2004-05-09. Archived from the original on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ Kalata, Kurt (2012-01-12). "Guardian Heroes". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ↑ "Top 20 Scrollers (Part 5) – #5, #4, #3 – Features". Game Observer. 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "RPGFan Reviews – Star Ocean". Rpgfan.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ↑ Hooking Up in Hyperspace (2010-04-13). "Hooking Up in Hyperspace | The Fanfiction Issue | The Escapist". Escapistmagazine.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "Granstream Saga – Review". Rpgamer.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- 1 2 "RPGFan Reviews – Legend of Mana". Rpgfan.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "RPGFan Reviews – Sword of Mana". Rpgfan.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ "RPGFan Reviews – Legend of Mana". Rpgfan.com. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Andrew Vestal (June 7, 2000). "Legend of Mana (review)". GameSpot.com. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ↑ Drifter, Tokyo (2008-09-27). "Review : Parasite Eve II review [PlayStation] - from GamePro.com". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2008-09-27. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Ishaan (November 10, 2012). "How Suikoden Influenced Deus Ex And Epic Mickey". Siliconera. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ↑ Thiboust, Jordane (24 January 2013). "Focusing Creativity: RPG Genres". Gamasutra. p. 3. Retrieved 29 December 2013.