Acoustic guitar

An acoustic guitar is a guitar that produces sound acoustically—by transmitting the vibration of the strings to the air—as opposed to relying on electronic amplification (see electric guitar). The sound waves from the strings of an acoustic guitar resonate through the guitar's body, creating sound. This typically involves the use of a sound board and a sound box to strengthen the vibrations of the strings.

The main source of sound in an acoustic guitar is the string, which is plucked or strummed with the finger or with a pick. The string vibrates at a necessary frequency and also creates many harmonics at various different frequencies. The frequencies produced can depend on string length, mass, and tension. The string causes the soundboard and sound box to vibrate, and as these have their own resonances at certain frequencies, they amplify some string harmonics more strongly than others, hence affecting the timbre produced by the instrument.

History

Gitterns, a small plucked guitar were the first small guitar-like instruments created during the Middle Ages with a round back like that of a lute.[1] Modern guitar shaped instruments were not seen until the Renaissance era where the body and size began to take a guitar-like shape.

The earliest string instruments that related to the guitar and its structure where broadly known as the vihuelas within Spanish musical culture. Vihuelas where string instruments that were commonly seen in the 16th century during the Renaissance. Later, Spanish writers distinguished these instruments into 2 categories of vihuelas. The vihuela de arco was an instrument that mimicked the violin, and the vihuela de penola was played with a plectrum or by hand. When it was played by hand it was known as the vihuela de mano. Vihuela de mano shared extreme similarities with the Renaissance guitar as it used hand movement at the sound hole or sound chamber of the instrument to create music.[2]

The real production of guitars kicked off in France where the popularity and production first began increasing with large quantities. Spain became the homeland of the guitar but there's very little information on the early makers there, unlike France, where many inventors and artists first began overproducing these instruments and their music. The production became so large that early famous creators such as Gaspard Duyffooprucgar's (a string instrument maker) instruments were being sold as copies by other guitar makers in Lyon. Benoist Lejeune, a guitar maker, offered and sold guitar copies of Duyffoprucgar's instruments and was later imprisoned for using his mark and work. During this time, the production was increasing tremendously but it was not until Robert and Claude Denis appeared overproducing the early Renaissance guitar in Paris, France. As father and son, Robert and Claude produced hundreds of guitars that increased the popularity of the instrument greatly. Because of them and the great many guitar inventors of this time, the word guiterne gradually shifted to guitarre during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[3]

By 1790 only six-course vihuela guitars (6 unison-tuned pairs of strings) were being created and had become the main type and model of guitar used in Spain. Most of the older 5-course guitars were still in use but were also being modified to a six-coursed acoustical guitar. Fernando Ferandiere's Book Arte de tocar la guitarra espanola por musica (Madrid, 1799) describes the standard Spanish guitar from his time as an instrument with seventeen frets and six courses with the first two 'gut' strings tuned in unison called the terceras and the tuning named to 'G' of the two strings. The acoustic guitar at this time really began to take its shape with extreme similarities to the acoustic guitar today with the exception of the coursed strings which later were removed for single strings instead of pairs.[4]

By the 19th century, coursed strings where evolved into 6 single-stringed instruments much like that of the guitar today. It had evolved into the modern look except for size, retaining a smaller frame.

Acoustic properties

The acoustic guitar's soundboard, or top, also has a strong effect on the loudness of the guitar. No amplification actually occurs in this process, because no external energy is added to increase the loudness of the sound (as would be the case with an electronic amplifier). All the energy is provided by the plucking of the string. But without a soundboard, the string would just "cut" through the air without actually moving it much. The soundboard increases the surface of the vibrating area in a process called mechanical impedance matching. The soundboard can move the air much more easily than the string alone, because it is large and flat. This increases the entire system's energy transfer efficiency, and a much louder sound is emitted.

|

Acoustic Guitar Sample

Spanish Romance. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

Acoustic Guitar Sample

An example of the sounds an acoustic guitar can create through vibration of its strings. This guitar uses steel strings. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

In addition, the acoustic guitar has a hollow body, and an additional coupling and resonance effect increases the efficiency of energy transmission in lower frequencies. The air in a guitar's cavity resonates with the vibrational modes of the string and soundboard. At low frequencies, which depend on the size of the box, the chamber acts like a Helmholtz resonator, increasing or decreasing the volume of the sound again depending on whether the air in the box moves in phase or out of phase with the strings. When in phase, the sound increases by about 3 decibels. In opposing phase, it decreases about 3 decibels.[5] As a Helmholtz resonator, the air at the opening is vibrating in or out of phase with the air in the box and in or out of phase with the strings. These resonance interactions attenuate or amplify the sound at different frequencies, boosting or damping various harmonic tones. Ultimately, the cavity air vibrations couple to the outside air through the sound hole,[6] though some variants of the acoustic guitar omit this hole, or have holes, like a violin family instrument (a trait found in some electric guitars such as the ES-335 and ES-175 models from Gibson). This coupling is most efficient because here the impedance matching is perfect: it is air pushing air.

A guitar has several sound coupling modes: string to soundboard, soundboard to cavity air, and both soundboard and cavity air to outside air. The back of the guitar also vibrates to some degree, driven by air in the cavity and mechanical coupling to the rest of the guitar. The guitar—as an acoustic system—colors the sound by the way it generates and emphasizes harmonics, and how it couples this energy to the surrounding air (which is ultimately what we perceive as loudness). Improved coupling, however, comes at the expense of decay time, since the string's energy is more efficiently transmitted. Solid body electric guitars (with no soundboard at all) produce very low volume, but tend to have long sustain.

All these complex air coupling interactions, and the resonant properties of the panels themselves, are a key reason that different guitars have different tonal qualities. The sound is a complex mixture of harmonics that give the guitar its distinctive sound.

Amplification

Classical gut-string guitars had little projection, and so were unable to displace banjos until innovations increased their volume.

Two important innovations were introduced by the American firm, Martin Guitars. First, Martin introduced steel strings. Second, Martin increased the area of the guitar top; the popularity of Martin's larger "dreadnought" body size amongst acoustic performers is related to the greater sound volume produced. These innovations allowed guitars to compete with and often displace the banjos that had previously dominated jazz bands. The steel-strings increased tension on the neck; for stability, Martin reinforced the neck with a steel truss rod, which became standard in later steel-string guitars.[8]

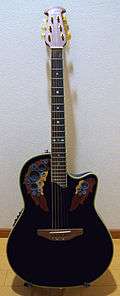

An acoustic guitar can be amplified by using various types of pickups or microphones. However, amplification of acoustic guitars had many problems with audio feedback. In the 1960s, Ovation's parabolic bowls dramatically reduced feedback, allowing greater amplification of acoustic guitars.[9] In the 1970s, Ovation developed thinner sound-boards with carbon-based composites laminating a thin layer of birch, in its Adamas model, which has been viewed as one of the most radical designs in the history of acoustic guitars. The Adamas model dissipated the sound-hole of the traditional soundboard among 22 small sound-holes in the upper chamber of the guitar, yielding greater volume and further reducing feedback during amplification.[9] Another method for reducing feedback is fit a rubber or plastic disc into the sound hole.

The most common type of pickups used for acoustic guitar amplification are piezo and magnetic pickups. Piezo pickups are generally mounted under the bridge saddle of the acoustic guitar and can be plugged into a mixer or amplifier. A Piezo pickup made by Baldwin was incorporated in the body of Ovation guitars, rather than attached by drilling through the body;[10] the combination of the Piezo pickup and parabolic ("roundback") body helped Ovation succeed in the market during the 1970s.[9]

Magnetic pickups on acoustic guitars are generally mounted in the sound hole, and are similar to those in electric guitars. An acoustic guitar with pickups for electrical amplification is called an acoustic-electric guitar.

In the 2000s, manufactures introduced new types of pickups to try to amplify the full sound of these instruments. This includes body sensors, and systems that include an internal microphone along with body sensors or under-the-saddle pickups.

Types

Historical and modern acoustic guitars are extremely varied in their design and construction, far more so than electric guitars. Some of the most important varieties are the classical guitar (nylon-stringed), steel-string acoustic guitar and lap steel guitar.

%2C_Matteo_Sellas%2C_The_Met%2C_NYC.jpg)

- Nylon/gut stringed guitars:

- Vihuela

- Gittern

- Baroque guitar

- Romantic guitar

- Classical guitar, the modern version of the original guitar, including additional strings models

- Lute

- Steel stringed guitars:

- Steel-string acoustic guitar, also known as western, folk or country guitar

- Twelve string guitar

- Resonator guitar (such as the Dobro)

- Archtop guitar

- Selmer/Maccaferri (Manouche) guitar

- Battente guitar

- Lap steel guitar

- Lap slide guitar

- Parlor guitar

- Lyre-guitar

- Other variants:

- Harp guitar

- Pikasso guitar (a variant of harp guitar)

- Contraguitar (Viennese variant of harp guitar)

- Acoustic bass guitar

- Banjo guitar

Body shape

Common body shapes for modern acoustic guitars, from smallest to largest:

Range – The smallest body shape, also considered a "mini jumbo", is three-quarters the size of a jumbo shaped guitar. A range shape typically has a rounded back which provides projection and volume for the smaller body.[11] The smaller body and scale length make the range guitar an option for players who struggle with larger body guitars.

Parlor – Parlor guitars have small compact bodies and have been described as “punchy” sounding with a delicate tone.[12] The smaller body makes the parlor a more comfortable option for players who find large body guitars uncomfortable.

Grand Concert – This mid-sized body shape is not as deep as other full-size guitars, but has a full waist. Because of the smaller body, grand concert guitars have a more controlled overtone[13] and are often used for its sound projection when recording.

Auditorium – Similar in dimensions to the dreadnought body shape,[14] but with a much more pronounced waist. The shifting of the waist provides different tones to stand out. The auditorium body shape is a newer body when compared to the other shapes such as dreadnought.

Dreadnought – This is the classic guitar body shape. Used for over 100 years, it is still the most popular body style for acoustic guitars.[15] The body is large and the waist of the guitar is not as pronounced as the auditorium and grand concert bodies. This allows mid-range frequencies to stand out, helping the guitar cut through an ensemble of instruments.

Jumbo – The largest standard guitar body shape found on acoustic guitars. The large body provides more punch and volume,[16] while accenting the “boomy” low end of the guitar.

Gallery

References

- ↑ "Gittern". www.medieval-life-and-times.info. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- ↑ Grunfeld, Frederic (1971). The Art and Times of the Guitar. 866 Third Avenue, New York: Macmillan Company. pp. 61–63.

- ↑ Turnbull, Harvey (1978). The Guitar from the Renaissance to the Present Day. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Tyler, James (2002). The Guitar and its Music. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 229–231. ISBN 978 0 19 921477 8.

- ↑ "Helmholtz Resonance". newt.phys.unsw.edu.au. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ "How does a guitar work?". newt.phys.unsw.edu.au. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ Carter (1996, p. 127)

- ↑ Denyer (1992), pp. 44–45

- 1 2 3 Denyer (1992, p. 48)

- ↑ Carter (1996, pp. 48–52)

- ↑ "Teton Range Guitars Demo - Home on the Range - Teton® Guitars". 2015-11-20. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ↑ "Parlor Pickin’: The 2015 Guide to Buying a Parlor Guitar". Acoustic Guitar. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ↑ "Grand Concert". Taylor Guitars. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ↑ "Auditorium Body Shape Overview". breedlovemusic.com. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ↑ "Dreadnought | Fender Acoustic Guitars". www.fender.com. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ↑ LTD., BubbleUp,. "Products by Body Type". Takamine Guitars. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

Further reading

- Carter, Walter (1996). Eiche, Jon, ed. The history of the Ovation guitar. Musical Instruments Series (first ed.). Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 1–128. HL00330187; ISBN 978-0-7935-5876-6; ISBN 0-7935-5876-X (softcover); ISBN 0-7935-5948-0 (hardcover).

- Denyer, Ralph (1992). The guitar handbook. Special contributors Isaac Guillory and Alastair M. Crawford; Foreword by Robert Fripp (Fully revised and updated ed.). London and Sydney: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-32750-X.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acoustic guitars. |

%2C_Kay_Kraft_guitar%2C_Museum_of_Making_Music.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2C_Museum_of_Making_Music.jpg)