Abrams Building

|

Abrams Building | |

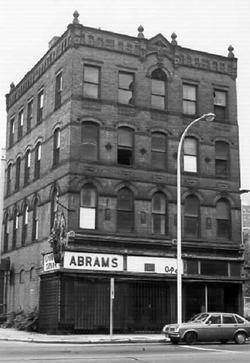

South profile and east elevation, 1979 | |

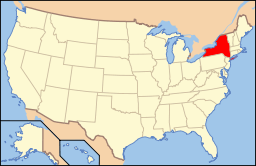

Location within the state of New York | |

| Location | Albany, NY |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°38′53″N 73°45′15″W / 42.64806°N 73.75417°WCoordinates: 42°38′53″N 73°45′15″W / 42.64806°N 73.75417°W |

| Built | 1885[1] |

| Demolished | 1987 |

| NRHP Reference # | 80002577[2] |

| Added to NRHP | February 14, 1980 |

The Abrams Building was located at South Pearl Street (New York State Route 32) and Hudson Avenue in Albany, New York, United States. It was a brick commercial building constructed in the 1880s. In 1980 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[2]

Originally it was part of a row of similar buildings. By the time it was listed, all of the adjoining buildings had been demolished, and it was one of the few 19th-century commercial building in Albany's downtown that retained its original storefront.[1] Seven years later, in 1987, it was demolished to make way for the future Knickerbocker Arena (now known as the Times Union Center).[3]

Building

The building was located on the northwest corner of the former intersection (Hudson was vacated west of South Pearl as part of the arena construction) at the south edge of Albany's downtown, just outside the Downtown Albany Historic District. Across the street commercial buildings of a similar age and scale, some of them contributing properties to the historic district, still stand. The South Mall Arterial, an elevated freeway providing access to the government buildings in Empire State Plaza from the Dunn Memorial Bridge over the Hudson River to the east, is a block to the south. Across the arterial are the Mansion and Pastures neighborhoods, both also listed on the National Register as historic districts.

The Abrams was a five-by-five-bay four-story brick structure with a flat roof. At the street level was the original storefront, with cast iron decorations. On the side elevations some splayed-lintel windows had been bricked in. An additional entrance, to the upper stories, was located on the south facade.[1]

All the second-story windows had round arches connected by molded brick stringcourses on the south (front) and side elevations. Atop them ran another stringcourse, with panels set between it and the third-story windows. They were topped in segmental arches connected by another stringcourse, and topped by panels with no top course. On the fourth story the central window had a rounded arch topped by a pediment that protruded into the paneled brick frieze. Another stringcourse connected its sill to those on the flanking windows, rectangular with flat lintels. All windows were set with one-over-one double-hung sash. At the roof there was a parapet with a small pediment in the center. On either side, and at the corner, were finials.[1]

Inside the ground floor had two commercial spaces, with original cabinetry and tin ceilings. The second floor was a large meeting space. On the third and fourth floors were apartments, many having had original finishes and fixtures.[1]

History

The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 onwards triggered growth in Albany that lasted well into the next century. It became an industrial and financial center in addition to the seat of state government. New residential neighborhoods, such as the Mansion and Pastures, were developed south of the city's core, and streets extended to them, with new development replacing earlier structures.[1]

One instance was the Abrams Building. It did not have that name at the time, but in 1885 Dr. John Bigelow, a professor at Albany Medical College, replaced an older, smaller structure his family owned. While there is no record of the architect, it bears a resemblance to the 1887 Albany Business College building, designed by the local firm of Ogden and Wright. Its Romanesque detailing was a popular style at the time.[1]

It was in use almost immediately. By 1890 the commercial space housed a liquor store. Later it would be a confectionery, jewelry store and drug store. The upstairs meeting space was also busy, with over a hundred different social and fraternal organizations active in Albany at that time. Among them were the Grand Army of the Republic and the Sons of Temperance (prior to the opening of the liquor store).[1]

In the late 20th century, the city's industries went into decline, and many of the buildings from its prosperous years suffered as well. Most were spared the wholesale destruction of urban renewal programs due to Albany politics, but some older buildings were demolished anyway. By the time the Abrams Building, which had taken the name of its then owner, was listed on the Register, it was the sole survivor of the row of similar buildings it once been part of.[1]

The owner hoped that the listing would help spur the restoration and redevelopment of the property, but instead it was condemned when the Albany Civic Center project (now the Times Union Center) was approved. Along with the Abrams, ten other historic buildings, some of them contributing properties to the Downtown Albany Historic District, were slated for destruction. Local preservationists tried to save them all. The federal Urban Mass Transit Administration denied the city a grant to build an elevated walkway connecting the arena to the government buildings at Empire State Plaza, since it indicated it would proceed with the demolition before a federal review required by the National Historic Preservation Act for any federal action that might affect Register-listed properties. The buildings were demolished early in 1987.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Harwood, John (October 25, 1979). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Abrams Building". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- 1 2 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 Sheffer, Gary (1987-01-26). "Civic Center Demolition to Get Started; 13 Buildings Being Stripped in Downtown Albany Will Come Down This Week". The Knickerbocker News. Hearst Newspapers. p. 3A. Retrieved 2011-07-09.