Abebe Bikila

| ||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native name | ሻምበል አበበ ቢቂላ | |||||||||||||||

| Full name | Abebe Bikila Demissie | |||||||||||||||

| Born |

August 7, 1932 Jato, Ethiopian Empire | |||||||||||||||

| Died |

October 25, 1973 (aged 41) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | |||||||||||||||

| Resting place |

Saint Joseph Church 8°58′11.57″N 38°46′1.51″E / 8.9698806°N 38.7670861°E | |||||||||||||||

| Height | 177 cm (5 ft 10 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Weight | 57 kg (126 lb) | |||||||||||||||

| Sport | ||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Athletics | |||||||||||||||

| Event(s) | Marathon | |||||||||||||||

| Achievements and titles | ||||||||||||||||

| Personal best(s) | Marathon: 2:12:11 (Tokyo 1964) | |||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||||

Abebe Bikila (Amharic: አበበ ቢቂላ?; August 7, 1932 – October 25, 1973) was an Ethiopian double Olympic marathon champion. He won the marathon at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome while running barefoot, setting a world record. At the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Abebe was the first athlete to successfully defend an Olympic marathon title, and broke his own world record in the process. He was a member of the Ethiopian Imperial Guard, an elite infantry division that safeguarded the Emperor of Ethiopia. Enlisting as a soldier before his athletic career, he rose to the rank of shambel (captain). In Ethiopia, Abebe is formally known as Shambel Abebe Bikila (Amharic: ሻምበል አበበ ቢቂላ?).

He was a pioneer in long-distance running. Mamo Wolde, Juma Ikangaa, Tegla Loroupe, Paul Tergat, and Haile Gebrselassie—all recipients of the New York Road Runners' Abebe Bikila Award—are a few of the athletes who have followed in his footsteps to establish East Africa as a force in long-distance running.[1][2][3] Abebe participated in a total of sixteen marathons, winning twelve and finishing fifth in the 1963 Boston Marathon. In July 1967, he sustained the first of several sports-related leg injuries which prevented him from finishing his last two marathons.

On March 22, 1969, Abebe was paralysed as a result of a car accident. Although he regained some upper-body mobility, he never walked again. Abebe competed in archery and table tennis at the 1970 Stoke Mandeville Games in London, an early predecessor of the Paralympic Games, while receiving medical treatment in England. He competed in both sports at a 1971 competition for the disabled in Norway, and won its cross-country sleigh-riding event.

Abebe died at age 41 on October 25, 1973, of a cerebral hemorrhage related to his accident four years earlier. He received a state funeral, and Emperor Haile Selassie declared a national day of mourning. Many schools, venues and events, including Abebe Bikila Stadium in Addis Ababa, are named after him. The subject of biographies and films documenting his athletic career, Abebe is often featured in publications about the marathon and the Olympics.

Biography

Early life

Abebe was born on August 7, 1932, in the small community of Jato, then part of the Debre Berhan district of Shewa.[4] His birthday coincided with the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Marathon.[5] Abebe was the son of Wudinesh Beneberu and her second husband, Bikila Demissie.[6] During the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, his family was forced to move to the remote town of Gorro.[7] By then, Wudinesh had divorced Abebe's father and married Temtime Kefelew.[6] The family eventually moved back to Jato (or nearby Jirru), where they had a farm.[7][8]

As a young boy Abebe played gena, a traditional long-distance hockey game played with goalposts sometimes miles apart.[6] Around 1952, he joined the 5th Infantry Regiment of the Imperial Guard after moving to Addis Ababa the year before.[9] During the mid-1950s, Abebe ran 20 km (12 mi) from the hills of Sululta to Addis Ababa and back every day.[8] Onni Niskanen, a Swedish coach employed by the Ethiopian government to train the Imperial Guard, soon noticed him and began training him for the marathon.[10] In 1956, Abebe finished second to Wami Biratu in the Ethiopian Armed Forces championship.[11] According to biographer Tim Judah, his entry in the Olympics was a "long planned operation" and not a last-minute decision (as commonly thought).[12]

Abebe married 15-year-old Yewebdar Wolde-Giorgis on March 16, 1960.[13][note 1] Although the marriage was arranged by his mother, Abebe was happy[8] and they remained married for the rest of his life.[14]

1960 Rome Olympics

In July 1960, Abebe won his first marathon in Addis Ababa.[15] A month later he won again in Addis Ababa with a time of 2:21:23, which would have broken the Olympic record held by Emil Zátopek.[16] Niskanen entered Abebe and Abebe Wakjira in the marathon at the 1960 Rome Olympics, which would be run on September 10.[17][18] In Rome Abebe purchased running shoes, but they did not fit well and gave him blisters;[19] he decided to run barefoot instead.[20]

The late-afternoon race started at the foot of the Capitoline Hill staircase[21] and finished at the Arch of Constantine, just outside the Colosseum.[22] The course twice passed Piazza di Porta Capena, where the Obelisk of Axum was then located.[21] When the runners passed the Obelisk the first time Abebe was at the rear of the lead pack, which included Arthur Keiley, Rhadi Ben Abdesselam, Bertie Messitt, and Aurèle Vandendriessche.[23]

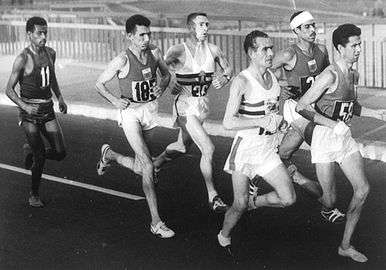

The lead pack near the 10 km (6 mi) mark, Abebe at the rear

The lead pack near the 10 km (6 mi) mark, Abebe at the rear Moving away from Ben Abdesselam

Moving away from Ben Abdesselam Crossing the finish line

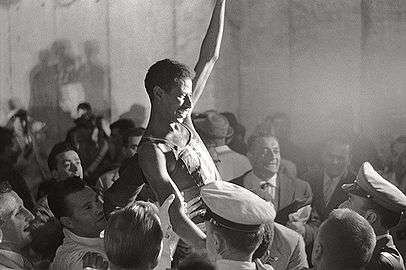

Crossing the finish line Celebrating outside the Colosseum

Celebrating outside the Colosseum

Between 5 km (3 mi) and 20 km (12 mi), the lead changed hands several times.[24] By about 25 km (16 mi), however, Abebe and Ben Abdesselam moved away from the rest of the pack.[25] They were trailed by Barry Magee and Sergei Popov, who were more than two minutes behind at the 30 km (19 mi) mark.[26]

Abebe and Ben Abdesselam remained together until the last 500 m (1,600 ft); nearing the Obelisk again, Abebe sprinted to the finish.[27] In the early-evening darkness, his path along the Appian Way was lined with Italian soldiers holding torches.[23][28] Abebe's winning time was 2:15:16.2, twenty-five seconds faster than Ben Abdesselam and breaking the world record by one-eighth of a second.[27] He became the first sub-Saharan African to win an Olympic gold medal.[29] Immediately after crossing the finish line Abebe began to touch his toes and run in place,[30] and later said that he could have run another 10–15 km (6–9 mi).[31]

1960–64

Abebe returned to his homeland a hero. He was greeted by a large crowd, many dignitaries and the commander of the Imperial Guard, Brigadier-General Mengistu Neway.[32] Abebe was paraded through the streets of Addis Ababa along a procession route lined with thousands of people and presented to Emperor Haile Selassie.[33] The emperor awarded him the Star of Ethiopia and promoted him to the rank of asiraleqa (corporal).[34] He was given the use of a chauffeur-driven Volkswagen Beetle (since he did not yet know how to drive) and a home, both owned by the Guard.[8][35]

On December 13, 1960, while Haile Selassie was on a state visit to Brazil, Imperial Guard forces led by Mengistu began an unsuccessful coup and briefly proclaimed Selassie's eldest son Asfaw Wossen Taffari emperor.[36][37] Fighting took place in the heart of Addis Ababa, shells detonated in the Jubilee Palace, and many of those closest to the emperor were killed.[38] Although Abebe was not directly involved, he was briefly arrested and questioned.[8][39] Mengistu was later hanged, and his forces (which included many members of the Imperial Guard) were killed in the fighting, arrested or fled.[40]

In the 1961 Athens Classical Marathon, Abebe again won while running barefoot.[41] However, he wore shoes for his victories in the Osaka and Košice marathons that year.[42][43]

Abebe entered the 1963 Boston Marathon and finished fifth, the only time in his competitive career that he completed an international marathon without winning.[44] He returned to Ethiopia and did not compete in another marathon until 1964 in Addis Ababa.[44][45] Abebe won that race in a time of 2:23:14.8.[15]

1964 Tokyo Olympics

Forty days before the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, while training in Debre Zeit, Abebe began to feel pain.[46] He was brought to the hospital and diagnosed with acute appendicitis,[46] and had an appendectomy on September 16.[47] Back on his feet in a few days, Abebe left the hospital within a week.[48]

He entered the October 21 marathon, this time wearing Puma shoes.[47] In 1961, he had been approached by a Japanese shoe company, Onitsuka Tiger, with the possibility of wearing its shoes; they were informed by Niskanen that Abebe had "other commitments." Kihachiro Onitsuka suspected that Abebe had a secret sponsorship deal with Puma, in spite of the now-abandoned rules against such deals.[49]

Abebe began the race right behind the lead pack until about the 10 km (6 mi) mark, when he slowly increased his pace.[50] At 15 km (9 mi) his only company was Ron Clarke of Australia in the lead, followed by Jim Hogan of Ireland and Abebe in third.[51] Shortly before 20 km (12 mi), Abebe took the lead; only Hogan was in contention, as Clarke began to slow.[50] By 35 km (22 mi), Abebe was almost two-and-a-half minutes in front of Hogan and Kokichi Tsuburaya of Japan was 17 seconds behind Hogan in third place.[51] Hogan soon dropped out, exhausted, leaving only Tsuburaya three minutes behind Abebe by the 40 km (25 mi) mark.[52]

Abebe entered the Olympic stadium alone, to the cheers of 75,000 spectators.[52] The crowd had been listening on the radio, and anticipated his triumphant entrance.[53] Abebe finished in a new world-record time of 2:12:11.2[54]—four minutes and eight seconds ahead of silver medalist Basil Heatley of Great Britain, who passed Tsuburaya inside the stadium.[55] Tsuburaya was third, a few seconds behind Heatley.[54] After the finish, not appearing exhausted, Abebe again performed a routine of calisthenics,[52] which included touching "his toes twice then [lying] down on his back, cycling his legs in the air."[53]

He was the first athlete in history to successfully defend the Olympic marathon title.[56] As of the 2016 Olympic marathon, Abebe and Waldemar Cierpinski were the only athletes to win two gold medals in the event.[57][58][59] For the second time, Abebe received Ethiopia's only gold medal[60] and again returned home to a hero's welcome.[61] The emperor promoted him to the commissioned-officer rank of metoaleqa (lieutenant).[8] Abebe received the Order of Menelik II, a Volkswagen Beetle and a house.[62]

1965–68

.jpg)

On April 21, 1965, as part of the opening ceremonies for the second season of the 1964–1965 New York World's Fair, Abebe and a fellow athlete and Imperial Guard, Mamo Wolde, ran a ceremonial half-marathon[63] from the Arsenal in Central Park (at 64th Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan) to the Singer Bowl at the fair.[64] They carried a parchment scroll with greetings from Haile Selassie.[65]

The following month, Abebe returned to Tokyo to win his second Mainichi Marathon.[15] In 1966 he ran marathons at Zarautz and Inchon–Seoul, winning both.[66][67] The following year, Abebe did not finish the Zarautz International Marathon in July 1967.[68] He had injured his hamstring, an injury from which he would never recover.[69] Abebe had begun to limp,[70] and the 1966 Incheon–Seoul Marathon was the last marathon he ever completed.[15]

In July 1968, he travelled to Germany for treatment of "circulatory ailments" in his legs;[71] the German government refused to accept payment for the medical services.[70] Abebe returned in time to join the rest of the Ethiopian Olympic team training in Asmara, which has an altitude (2,200 m or 7,200 ft) and climate similar to Mexico City (the host of the next Olympic Games).[72]

Seeking a third consecutive gold medal, Abebe entered the October 20 Olympic marathon with Mamo Wolde and Gebru Merawi.[73] Symbolically, he was issued bib number 1 for the race.[74] A week before the race, Abebe developed pain in his left leg. Doctors discovered a fracture in his fibula, and he was advised to stay off his feet until the day of the race.[75] Abebe had to drop out of the race after approximately 16 km (10 mi),[76][77] and it was his last marathon appearance.[15] Nonetheless, he was promoted to the rank of shambel (captain) upon his return to Ethiopia.[78]

Accident and death

On the night of March 22, 1969, Abebe lost control of his Volkswagen Beetle; it overturned, trapping him inside.[79] According to biographer Tim Judah, he may have been drinking.[80][81] Judah quotes Abebe's account of the accident from the biography by his daughter, Tsige Abebe, that he tried "to avoid a fast, oncoming car". Judah wrote that it was difficult to know for certain what happened.[81] Abebe was freed from his car the following morning and brought to the Imperial Guard hospital.[79] The accident left him a quadriplegic, paralysed from the neck down; he never walked again.[82] On March 29 Abebe was transferred to Stoke Mandeville Hospital in England,[83] where he spent eight months receiving treatment.[84] He was visited by Queen Elizabeth II and received get-well cards from all over the world.[85] Although Abebe could not move his head at first, his condition eventually improved to paraplegia, regaining the use of his arms.[82][86]

In 1970, Abebe began training for wheelchair-athlete archery competitions.[87] In July, he competed in archery and table tennis at the Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Games in London.[88] The following April, Abebe participated in games for the disabled in Norway.[89] Although he had been invited as a guest, he competed in archery and table tennis and defeated a field of sixteen in cross-country sled dog racing with a time of 1:16:17.[90]

Abebe was invited to the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich as a special guest, and received a standing ovation during the opening ceremony.[90] His countryman Mamo Wolde did not match his back-to-back Olympic marathon victories,[91] finishing third behind Frank Shorter of the United States and Karel Lismont of Belgium.[92] After Shorter received his gold medal, he shook Abebe's hand.[82]

On October 25, 1973, Abebe died in Addis Ababa at age 41 of a cerebral hemorrhage, a complication related to his accident four years earlier.[19][93] He was buried with full military honours; his state funeral was attended by an estimated 65,000 people including Haile Selassie, who proclaimed a day of mourning for the country's national hero.[94][95] Abebe was interred in a tomb with a bronze statue at Saint Joseph Church in Addis Ababa.[14]

Legacy

Abebe began, and largely inspired, East African preeminence in long-distance running.[1] According to Kenny Moore, a contemporary athlete and writer for Sports Illustrated, he began "the great African distance running avalanche."[96] Abebe brought to the forefront the now-accepted relationship between endurance and high-altitude training.[29][97] Five years after his death, the New York Road Runners inaugurated the annual Abebe Bikila Award for contributions by an individual to long-distance running.[98] East African recipients include Mamo Wolde, Juma Ikangaa, Tegla Loroupe, Paul Tergat, and Haile Gebrselassie.[99][100]

He is a national hero in Ethiopia,[93] and a stadium in Addis Ababa is named in his honour.[101] In late 1972, the American Community School of Addis Ababa dedicated its gymnasium (which included facilities for the disabled) to Abebe.[19][90]

On March 21, 2010, the Rome Marathon observed the 50th anniversary of his Olympic victory.[102] The winner, Ethiopian runner Siraj Gena, ran the last 300 m (984 ft) of the race barefoot and received a €5,000 bonus.[103] A plaque commemorating the anniversary is mounted on a wall on the Via di San Gregino, and a footbridge in Ladispoli was named in Abebe's honour.[104]

According to Abebe's New York Times obituary, Abebe and Yewebdar had three sons along with their daughter Tsige.[93] In 2010, the Italian company Vibram introduced the "Bikila" model of its FiveFingers line of minimalist shoes.[98] In February 2015, Abebe's surviving children Teferi, Tsige and Yetnayet Abebe Bikila, along with their mother, filed a lawsuit in US federal court in Tacoma, Washington accusing Vibram violated federal law and the state's Personality Rights Act.[105][106] The case was dismissed in October 2016 on the grounds that the plaintiffs were aware of Vibram's use of the name in 2011 but did not file suit until four years later. According to judge Ronald Leighton, "this unreasonable delay prejudiced Vibram."[98][106]

In popular culture

Abebe's victory at the 1964 Olympics was featured in the 1965 documentary, Tokyo Olympiad.[107][108] Footage from that film was recycled in the 1976 thriller, Marathon Man.[109]

Abebe was the subject of Bud Greenspan's 1972 documentary, The Ethiopians.[19] It was incorporated into The Marathon, a 1976 episode of Greenspan's The Olympiad television documentary series. The Marathon, which chronicles Abebe's two Olympic victories, ends with a dedication ceremony for a gymnasium named in his honour shortly before his death.[110]

Triumph and Tragedy is a biography written by his daughter, Tsige Abebe,[111] which was published in Addis Ababa in 1996.[82] Paul Rambali's Barefoot Runner is a 2007 biographical novel based on Abebe's life.[80] Bikila: Ethiopia's Barefoot Olympian, by Tim Judah, was published in 2009. According to the journalist Tim Lewis' comparative review of the books, Judah's is a more journalistic, less-forgiving biography of Abebe.[80] It refutes the mythical aspects of his life but recognises Abebe's athletic accomplishments.[29][81] Its account of his life differs significantly from Rambali's, but confirms (and frequently cites) Tsige's biography.[112] For example, Lewis cites the discrepancy in the circumstances surrounding Abebe's car accident:

Rambali pictures Bikila driving to training in his VW Beetle, only to be forced off the road by a group of students ('screaming, blood-covered young men') who are being chased by armed police. The facts uncovered by Judah point to a less poetic explanation: Bikila was last seen in a bar at 9pm, the roads that night were wet and he was inexperienced behind the wheel.[80]

Atletu (The Athlete), a 2009 film directed by Davey Frankel and Rasselas Lakew, focuses on the final years of Abebe's life: his quest to regain the Olympic title, the accident and his struggle to compete again.[113][114] Robin Williams referred to Abebe's barefoot running during his 2009 stand-up comedy tour, Weapons of Self-Destruction: "[Abebe] won the Rome Olympics running barefoot. He was then sponsored by Adidas. He ran the next Olympics; he carried the fucking shoes".[115][116][117] Of course, Abebe did not actually carry his shoes but wore them; he was not sponsored by Adidas but was perhaps secretly sponsored by Puma.[49][118]

Marathon performances

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representing | ||||||

| 1960 | Armed Forces championship[119] | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | 1st | 2:39:50 | ||

| Olympic trials | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | 1st | 2:21:23 | |||

| Olympic Games | Rome, Italy | 1st | 2:15:16.2 | |||

| 1961 | Athens International Marathon | Athens, Greece | 1st | 2:23:44.6 | ||

| Mainichi Marathon | Osaka, Japan | 1st | 2:29:27 | |||

| Košice Marathon | Košice, Czechoslovakia | 1st | 2:20:12.0 | |||

| 1963 | Boston Marathon | Boston, USA | 5th | 2:24:43a | ||

| 1964 | Armed Forces championship | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | 1st | 2:23:14.8 | ||

| Olympic trials | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | 1st | 2:16:18.8 | |||

| Olympic Games | Tokyo, Japan | 1st | 2:12:11.2 | |||

| 1965 | Mainichi Marathon | Tokyo, Japan | 1st | 2:22:55.8 | ||

| 1966 | Zarautz International Marathon | Zarautz, Spain | 1st | 2:20:28.8 | ||

| Inchon–Seoul Marathon | Seoul, South Korea | 1st | 2:17:04a | |||

| 1967 | Zarautz International Marathon | Zarautz, Spain | DNF | |||

| 1968 | Olympic Games | Mexico City, Mexico | DNF | |||

See also

- Ethiopia at the Olympics

- Sport in Ethiopia

- Marathon world record progression

- List of athletes who have competed in the Paralympics and Olympics

Notes

References

- 1 2 Benyo & Henderson (2002), p. 3

- ↑ Pitsiladis, Wang & Wolfarth (2011), p. 186

- ↑ Gebreselassie (2006)

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 23

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 238

- 1 2 3 Judah (2008), p. 24

- 1 2 Judah (2008), p. 26

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Underwood (1965), p. 86–92

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 27, 28

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 54

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 59

- ↑ Judah (2008), pp. 59–60

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 30

- 1 2 Judah (2008), p. 161

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 ARRS. "Runner: Abebe Bikila"

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 68–69

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 69

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 229

- 1 2 3 4 Greenspan (1989), p. 14

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 239

- 1 2 Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 232

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 230

- 1 2 Maraniss (2008)

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), pp. 234–35

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 235

- ↑ Giacomini, Vignolini & Baggio (1960), p. 123

- 1 2 Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 236

- ↑ Daley (1966)

- 1 2 3 Judah (2008), p. 17

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 84

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 85

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 94

- ↑ Judah (2008), pp. 94–95

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 95

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 96

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 98

- ↑ Clapham (1968)

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 101

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 103

- ↑ Judah (2008), pp. 102–104

- ↑ Associated Press (May 8, 1961). "Ethiopian Runs Barefooted, Set Marathon Mark". St. Joseph Gazette. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Race: Mainichi 1961". ARRS. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Race: Kosice 1961". ARRS. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- 1 2 Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 245

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 113

- 1 2 Judah (2008), p. 118

- 1 2 Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 248

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 119

- 1 2 Judah (2008), pp. 124–25

- 1 2 Judah (2008), p. 126

- 1 2 Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 250

- 1 2 3 Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 251

- 1 2 Judah (2008), p. 128

- 1 2 Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 254

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 253

- ↑ Associated Press (October 22, 1964). "Fastest Marathon Ever and Abebe Did Not Tire". Calgary Herald. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 322

- ↑ "NBA stars set to bring curtain down on Rio Games". AFP. August 21, 2016. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ↑ Kyeyune, Darren A. (August 21, 2016). "Kiprotich fails to defend Olympic marathon title". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ↑ Richman, Milton (October 27, 1964). "Skinny Ethiopian Toast of the Olympics". The Deseret News. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 132–133

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 133

- ↑ Phillips, Mccandlish (April 22, 1965). "Lo, a Magic City Awakens and Wizard Rejoices ...". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Alden, Robert (April 4, 1965). "The Fair Resumes Today With Many New Exhibits ...". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Jones, Theodore (April 4, 1965). "Ethiopia Marathon Star Here for Fair". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Race: Zarauz International 1966". ARRS. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Race: Inchon-Seoul 1966". ARRS. Archived from the original on January 20, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Race: Zarauz International 1967". ARRS. Archived from the original on January 20, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 255

- 1 2 Judah (2008), p. 142

- ↑ "Bikila, Ethiopian Runner, To Undergo Leg Treatment". The New York Times. Associated Press. July 21, 1968. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 143

- ↑ Associated Press (October 2, 1968). "Bikila Seeks Third Marathon". The Montreal Gazzette. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 146

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 144–145

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 268

- ↑ Cady, Steve (October 21, 1968). "Wolde of Ethiopia Takes Marathon in 2 Hours 20 Minutes 26.4 Seconds ...". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 151

- 1 2 Judah (2008), p. 153

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis, Tim (July 26, 2008). "Triumph of the shoeless superstar". The Guardian. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Judah (2008), p. 154

- 1 2 3 4 Benyo, Richard; Henderson, Joe (2002). Running Encyclopedia. Human Kinetics. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-7360-3734-1. OCLC 47665415.

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 155

- ↑ "Crippled Bikila Set To Leave Hospital". The New York Times. Reuters. November 23, 1969. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 156

- ↑ Judah (2008), pp. 155–58

- ↑ Farrow, John (January 9, 1970). "Paralyzed Olympic champion turns to wheelchair archery". The Evening Sun. Hanover, Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 1, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Shaw, Peter J. (August 26, 1970). "Crippled Olympic champ plays in wheelchair sports". Courier-Post. Camden, New Jersey. Retrieved January 27, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Martin, Simon (April 25, 2012). "50 stunning Olympic moments No24: Abebe Bikila runs barefoot into history". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 17, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Judah (2008), p. 158

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), p. 292

- ↑ Martin & Gynn (2000), pp. 288–91

- 1 2 3 Associated Press (October 26, 1973). "Abebe Bikila, 46, Track Star, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 159

- ↑ Sears, Edward S. (June 8, 2015). Running Through the Ages, 2d ed. McFarland. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-4766-2086-2. OCLC 910878812.

- ↑ Moore, Kenny (December 4, 1995). "The End of the World". Sports Illustrated. pp. 78–95. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 64

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Gene (November 1, 2016). "Lawsuit over use of barefoot marathoner's name is dismissed". AP News. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Radcliffe Is 2006 Bikila Award Winner". Runner's World. October 27, 2006. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- ↑ "Gebrselassie, Loroupe, Radcliffe and Tergat To Be Inducted Into NYRR Hall of Fame". Competitor.com. October 21, 2015. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- ↑ Magasela, Bongani (March 25, 2001). "Ethiopian soccer fined for soccer louts". SAPA. Archived from the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ↑ Sampaolo, Diego (March 19, 2010). "Barus and Dado the favourites as Rome celebrates 50th Anniversary of Bikila's Olympic triumph – preview". IAAF. Archived from the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ↑ Sampaolo, Diego (March 21, 2010). "Ethiopian double as Rome celebrates Bikila – Rome Marathon report". IAAF. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ↑ Urbano, Giuseppe (May 26, 2016). "Storia delle Olimpiadi: Abebe Bikila. La guardia del corpo di Selassié che vinse, scalzo, la maratona di Roma 1960". OA (in Italian). Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- ↑ Associated Press (February 10, 2015). "Barefoot marathon runner's family sues Vibram". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- 1 2 Judge Leighton, Ronald B. (October 31, 2016). "Bikila v. Vibram USA Inc.: Order Granting Defendants' Motion" (PDF). Justia. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ↑ Ichikawa, Kon (March 20, 1965). 東京オリンピック (Tôkyô orinpikku) [Tokyo Olympiad] (Film) (in Japanese). Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ↑ Benyo & Henderson (2002), p. 224

- ↑ Schlesinger, John (October 8, 1976). Marathon Man (Film). Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ Greenspan, Bud (May 16, 1976). "The Marathon". The Olympiad. OCLC 5645282. CTV. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ↑ Abebe, Tsige (1996). Triumph and Tragedy: A History of Abebe Bikila and His Marathon Career. Addis Ababa: Artistic Printers.

- ↑ Judah (2008), p. 13: "I have quoted from it several times."

- ↑ Frankel, Davey; Lakew, Rasselas (2013). The Athlete (Motion picture). Grand Entertainment Group. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Olsen, Mark (November 29, 2012). "Movie review: 'The Athlete' stumbles in storytelling". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ↑ Callner, Marty (Director) (December 6, 2009). "Robin Williams: Weapons of Self Destruction".

- ↑ Husband, Andrew (August 8, 2014). "Robin Williams and Abebe Bikila". Stride Nation. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ Giddings, Caitlin (2014-08-12). "Robin Williams Had Deep Running Roots". Runner's World. Retrieved 2017-08-03.

- ↑ Kobayashi, Koji; Amis, John M.; Unwin, Richard; Southhall, Richard (2013-09-13). "Japanese post-industrial management: the cases of Asics and Mizuno". In Westerbeek, Hans. Global Sport Business: Community Impacts of Commercial Sport. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 9781317991281.

- ↑ Judah (2008), pp. 68

Sources

Books

|

Periodicals

Online sources

|

Further reading

- Rambali, Paul (2006). Barefoot runner: the life of marathon champion Abebe Bikila. London: Serpent's Tail. ISBN 978-1-85242-904-1. OCLC 068263333.

- Yamada, Kazuhiro (1992). Abebe o oboetemasuka アベベを覚えてますか [Do you remember Abebe] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 4-480-02626-6. OCLC 674609983.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abebe Bikila. |

- Abebe Bikila's Profile on Olympic.org

- Video tribute to Abebe Bikila on YouTube

- Video footage of Abebe Bikila at the 1960 Summer Olympics

- Marathon portion of 1965 documentary Tokyo Olympiad.

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by |

Men's Marathon World Record Holder September 10, 1960 – February 17, 1963 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by |

Men's Marathon World Record Holder October 21, 1964 – June 12, 1965 |

Succeeded by |