Abdominal examination

The abdominal exam, in medicine, is performed as part of a physical examination, or when a patient presents with abdominal pain or a history that suggests an abdominal pathology.

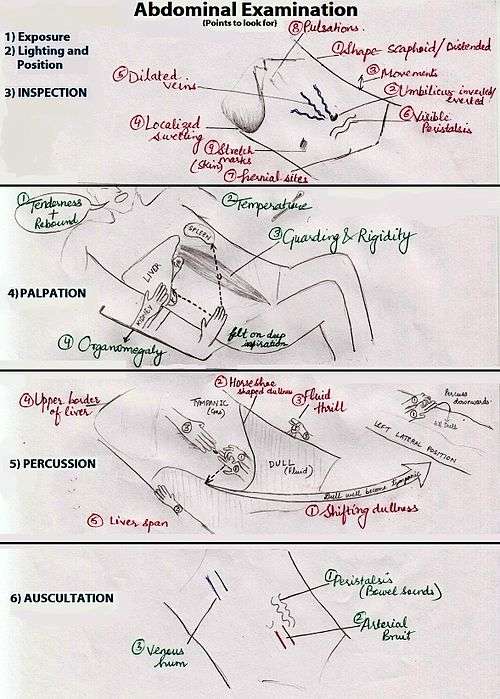

The abdominal exam has conventionally been split into different stages:

- Preparation/Positioning of the patient.

- Inspection of the patient and their the visible characteristics of their abdomen.

- Auscultation of the abdomen with a stethoscope.

- Palpation of the patient's abdomen and abdominal organs.

- Percussion of the patient's abdomen.

- Special tests performed based on the need to inspect for signs of various abdominal diseases.[1]

Purpose

According to Mosby's, "The abdominal exam is performed as part of the comprehensive physical examination or when a patient presents with signs of symptoms of an abdominal disease process." In other words, your doctor will often perform an abdominal exam as part of a routine examination. However, your doctor might perform additional tests if your doctor feels that you might have an abdominal disease.

Positioning and environment

A suggested position is for the patient to be supine (on their back), with their arms to their sides. The patient should be placed in an environment with good lighting, and should be draped with towels or sheets to preserve privacy and warmth

Although physicians have had concern that giving patients pain medications during acute abdominal pain may hinder diagnosis and treatment, separate systematic reviews by the Cochrane Collaboration[2] and the Rational Clinical Examination[3] refute this.

Inspection

The abdominal exam typically begins a visual examination of the abdomen. Some common things an examiner might look for are:

- masses

- scars

- lesions

- abdominal distension

In addition, a doctor might look/check for specific signs of disease, such as:

Auscultation

Auscultation refers to the use of a stethoscope by the examiner to listen to sounds from the abdomen. This is a very subjective procedure.

Unlike other physical exams, auscultation is performed prior to percussion or palpation, because both might alter abdominal sounds.

Some controversy exists as to the length of time required to confirm or exclude bowel sounds, with suggested durations up to seven minutes. Bowel obstruction may present with grumbling bowel sounds or high-pitched noises. Healthy persons can have no bowel sounds for several minutes [4] and intestinal contractions can be silent.[5] Absence of sounds may be caused by peritonitis, paralytic ileus, bowel obstruction, intestinal ischemia or other causes.[6] Some authors suggest that listening at a single location is enough as sounds can be transmitted throughout the abdomen.[7]

A prospective study published in 2014 where 41 physicians listened to the bowel sounds of 177 volunteers (19 of which had bowel obstructions and 15 with an ileus) found that "Auscultation of bowel sounds is not a useful clinical practice when differentiating patients with normal versus pathologic bowel sounds. The listener frequently arrives at an incorrect diagnosis. Agreement between raters was also low (54%).".[8] This article suggests focusing on other indicators (flatus, pain, nausea) instead. There is no research evidence that reliably corroborates the assumed association between bowel sounds and gastro-intestinal motility status.[9]

The examiner also typically listens to the two renal arteries for bruits by listening in each upper quadrant, adjacent to and above the umbilicus. Bruits heard in the epigastrium that are confined to systole are considered normal.[10]

Palpation

The examiner typically palpates all nine areas of the patient's abdomen. This is typically performed twice, lightly and then deeply.

On light palpation, the examiner tests for any palpable mass, rigidity, or pain.

On deep palpation, the examiner is testing for and organomegaly, including enlargement of the liver and spleen.

Reactions that may indicate pathology include:

- guarding, describing muscle contraction as pressure is applied.

- rigidity, indicating peritoneal inflammation.

- rebound, pain on release

- hernial orifices if positive cough impulses.

Percussion

The examiner, mindful of areas of discomfort, begins by palpating areas of no pain. Percussion is performed by knocking the middle finger against the phalanx of the middle finger of the opposing hand, which rests against the surface of the abdomen in each of the nine areas tested. Percussion can elicit a painful response in the patient, and may also reveal whether there is abnormal levels of fluid in the abdomen. Organomegaly may also be noted, including gross splenomegaly (enlargement of the spleen), hepatomegaly (enlargement of the liver), and urinary retention.

The examiner, when percussing for organomegaly, percusses in a particular manner:

- percuss the liver from the right iliac region to right hypochondrium

- percuss for the spleen from the right iliac region to the right hypochondrium and the left iliac to the left hypochondrium.

Examination of the spleen

- Castell's sign or alternatively Traube's space

Other and special maneuvers

- Examination of pelvic lymph nodes

- Digital rectal exam – Abdominal examination is not complete without a digital rectal exam.

- Pelvic examination only if clinically indicated.

Special manevures may also be performed, to elicit signs of specific diseases. These include

- Gallbladder: Murphy's sign

- Appendicitis or peritonitis:

- Psoas sign – pain when tensing the psoas muscle

- Obturator sign – pain when tensing the obturator muscle

- Rovsing's sign – pain in the right iliac fossa on palpation of the left side of the abdomen

- Carnett's sign – pain when tensing the abdominal wall muscles

- Patafio's sign – pain when the patient is asked to cough whilst tensing the psoas muscle

- Cough test – pain when the patient is asked to cough

- Suspected Pyelonephritis: Murphy's punch sign

- Hepatomegaly: Liver scratch test

- Ascites: bulging flanks, fluid wave test, shifting dullness

References

- ↑ Seidel, Henry M.; Ball, Jane W.; Dains, Joyce E.; Flynn, John A.; Solomon, Barry S.; Stewart, Rosalyn W. (2011). Mosby's Guide to Physical Examination (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. pp. 492–513. ISBN 978-0-323-05570-3.

- ↑ Manterola C, Astudillo P, Losada H, Pineda V, Sanhueza A, Vial M (2007). Manterola C, ed. "Analgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD005660. PMID 17636812. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005660.pub2.

- ↑ Ranji SR, Goldman LE, Simel DL, Shojania KG (2006). "Do opiates affect the clinical evaluation of patients with acute abdominal pain?". JAMA. 296 (14): 1764–74. PMID 17032990. doi:10.1001/jama.296.14.1764.

- ↑ McGee, S, Evidence-Based Physical Diagnosis, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier-Saunders; 2012

- ↑ http://blogs.jwatch.org/frontlines-clinical-medicine/2017/03/01/listening-bowel-sounds-outdated-practice/

- ↑ Jarvis, C.(2008). Physical Examination and Health Assessment. 5th edn. Saunders Elsevier, St Louis

- ↑ Reuben, A. (2016). Examination of the abdomen. Clinical Liver Disease, 7(6), 143–150. doi:10.1002/cld.556

- ↑ Felder, S., Margel, D., Murrell, Z., & Fleshner, P. (2014). Usefulness of Bowel Sound Auscultation: A Prospective Evaluation. Journal of Surgical Education, 71(5), 768–773. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.02.003

- ↑ Massey RL. Return of bowel sounds indicating an end of postoperative ileus: is it time to cease this long-standing nursing tradition? Medsurg Nurs . 2012;21(3):146–150

- ↑ MD, Lynn B. Bates' Guide to Physical Examination and History-Taking, 11th Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 11/2012.

External links

- Abdominal exam – a practical guide to clinical medicine from the University of California, San Diego.