A Season in Hell

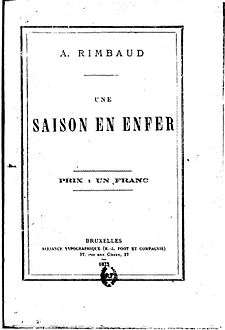

A Season in Hell (French: Une Saison en Enfer) is an extended poem in prose written and published in 1873 by French writer Arthur Rimbaud. It is the only work that was published by Rimbaud himself. The book had a considerable influence on later artists and poets, including the Surrealists.

Writing and publication history

Rimbaud began writing the poem in April 1873 during a visit to his family's farm in Roche, near Charleville on the French-Belgian border. According to Bertrand Mathieu, Rimbaud wrote the work in a dilapidated barn.[1]:p.1 In the following weeks, Rimbaud traveled with poet Paul Verlaine through Belgium and to London again. They had begun a complicated relationship in spring 1872, and they quarreled frequently.[2]

Verlaine had bouts of suicidal behavior and drunkenness. When Rimbaud announced he planned to leave while they were staying in Brussels in July 1873, Verlaine fired two shots from his revolver, wounding Rimbaud once. After subsequent threats of violence, Verlaine was arrested and incarcerated to two years hard labour. After their parting, Rimbaud returned home to complete the work and published A Season in Hell. However, when his reputation was marred because of his actions with Verlaine, he received negative reviews and was snubbed by Parisian art and literary circles. In anger, Rimbaud burned his manuscripts and likely never wrote poetry again.

According to some sources, Rimbaud's first stay in London in September 1872 converted him from an imbiber of absinthe to a smoker of opium, and drinker of gin and beer. According to biographer, Graham Robb, this began "as an attempt to explain why some of his [Rimbaud's] poems are so hard to understand, especially when sober".[3] The poem was by Rimbaud himself dated April through August 1873, but these are dates of completion. He finished the work in a farmhouse in Roche, Ardennes.

There is a marked contrast between the hallucinogenic quality of Une Saison's second chapter, "Mauvais Sang" ("Bad Blood") and even the most hashish-influenced of the immediately preceding verses that he wrote in Paris. Its third chapter, "Nuit de l'Enfer" (literally "Night of Hell"), then exhibits a refinement of sensibility. The two sections of chapter four apply this sensibility in professional and personal confession; and then, slowly but surely, at age 18, he begins to think clearly about his real future; the introductory chapter being a product of this later phase.

Format

The prose poem is loosely divided into nine parts, some of which are much shorter than others. They differ markedly in tone and narrative comprehensibility, with some, such as "Bad Blood," 'being much more obviously influenced by Rimbaud's drug use than others, some argue. However, it is a well and deliberately edited and revised text. This becomes clear if one compares the final version with the earlier versions.[4]

- Introduction (sometimes titled with its first line, "Once, if my memory serves me well...") (French: Jadis, si je me souviens bien...) – outlines the narrator's damnation and introduces the story as "pages from the diary of a Damned soul."

- Bad Blood ("Mauvais sang") – describes the narrator's Gaulish ancestry and its supposed effect on his morality and happiness.

- Night of hell ("Nuit de l'enfer") – highlights the moment of the narrator's death and entry into hell.

- Delirium 1: The Foolish Virgin – The Infernal Spouse ("Délires I: Vierge folle – L'Époux infernal") – the most linear in its narrative, this section consists of the story of a man (Verlaine), enslaved to his "infernal bridegroom" (Rimbaud) who deceived him and lured his love with false promises. He treats quite transparently his relation with Verlaine.

- Delirium 2: Alchemy of Words ("Délires II: Alchimie du verbe") – the narrator then steps in and explains his own false hopes and broken dreams. This section is broken up much more clearly than many other sections and contains many sections in verse. Here Rimbaud continues to develop his theory of poetry that began with his "Lettres du Voyant", the "Letters of the Seer".[5]

- The Impossible ("L'impossible") – this section is vague, but one critical response sees it as the description of an attempt on the part of the speaker to escape from hell.

- Lightning ("L'éclair") – one critic states that this very short section is also unclear, although its tone is resigned and fatalistic and it seems to indicate a surrender on the part of the narrator.

- Morning ("Matin") – this short section serves as a conclusion, where the narrator claims to have "finished my account of my hell," and "can no longer even talk."

- Farewell ("Adieu") – this section seems to allude to a change of seasons, from Autumn to Spring. The narrator seems to have been made more confident and stronger through his journey through hell, claiming he is "now able to possess the truth within one body and one soul."

Interpretation

Mathieu describes A Season in Hell as "a terribly enigmatic poem", and a "brilliantly near-hysterical quarrel between the poet and his 'other'."[1]:p.1 He identifies two voices at work in the surreal narrative: "the two separate parts of Rimbaud’s schizoid personality—the 'I' who is a seer/poet and the 'I' who is the incredibly hard-nosed Widow Rimbaud’s peasant son. One voice is wildly in love with the miracle of light and childhood, the other finds all these literary shenanigans rather damnable and 'idiotic'."[1]:pp.1–2

For Wallace Fowlie writing in the introduction to his 1966 University of Chicago (pub) translation, "the ultimate lesson" of this "complex"(p4) and "troublesome"(p5) text states that "poetry is one way by which life may be changed and renewed. Poetry is one possible stage in a life process. Within the limits of man's fate, the poet's language is able to express his existence although it is not able to create it."(p5) According to Mathieu: "The trouble with A Season in Hell is that it points only one way: where it’s going is where it’s coming from. Its greatest source of frustration, like that of every important poem, is the realization that it’s impossible for any of us to escape the set limits imposed on us by 'reality.'"[1]:p.2

Academic critics have arrived at many varied and often entirely incompatible conclusions as to what meaning and philosophy may or may not be contained in the text.

Among them, Henry Miller was important in introducing Rimbaud to America in the sixties. He once attempted an English translation of the book and wrote an extended essay on Rimbaud and A Season in Hell titled The Time of the Assassins. It was published by James Laughlin's New Directions, the first American publisher of Rimbaud's Illuminations.

Wallace in 1966, p5 of above-quoted work, "...(a season in Hell) testif(ies) to a modern revolt, and the kind of liberation which follows revolt".

Translations

During one of her lengthy hospitalizations in Switzerland, Zelda Fitzgerald translated Une Saison en Enfer. Earlier Zelda had learned French on her own, by buying a French dictionary and painstakingly reading Raymond Radiguet's Le Bal du Comte d'Orgel.

Wallace Fowlie translated the poem for his Rimbaud: Complete Works, Selected Letters in 1966.[6]

In popular culture

- The title of the novel is also the title of Eddie Wilson's unreleased final album from the cult film Eddie and the Cruisers (1983).

- The book was referenced in the Felt song, "Sunlight Bathed the Golden Glow" from their album, The Strange Idols Pattern and Other Short Stories (1984), with the lyric "you're reading from A Season in Hell but you don't know what it's about".

- The French poet-composer Léo Ferré set to music, sang and told the whole poem in the album Une saison en enfer (1991).

- In the film Pollock (2000), Lee Krasner (played by Marcia Gay Harden) reads a quote from A Season in Hell, written on the wall of her studio, when she first receives a visit from Jackson Pollock (played by Ed Harris):

- "To whom shall I hire myself out?

- What beast must I adore?

- What holy image is attacked?

- What hearts must I break?

- What lie must I maintain? In what blood tread?"

- Author Tom Robbins wrote a book called Fierce Invalids Home from Hot Climates (2000). This title is a line from A Season in Hell.

- Moby's album Last Night (2008) includes the track "Hyenas" in which a female voice reads the first several lines of A Season in Hell in the original French.

- In the game Tales of Symphonia: Dawn of the New World, an antagonist named Alice has attacks that are all named after famous literary works. (e.g. The Red and the Black is a historical French novel, A Season in Hell is a French poem etc.)

- A Season in Hell is quoted in the novels The Ghosts of Watt O'Hugh[7] by Steven S. Drachman and As Simple As Snow[8] by Gregory Galloway. Watt O'Hugh is a 2011 novel that features J. P. Morgan as a principal character. In the novel, Morgan reads Une Saison on Enfer in his study, moments before being visited by the ghost of his first wife. The novel was named one of the best of 2011 by Kirkus Reviews.[9]

- A Season in Hell was quoted several times in the album Pretty. Odd. (2008) by Panic! at the Disco.

- Contemporary artist Alex Da Corte has cited A Season in Hell as a major influence on his work, most notably in his video A Season in Hell, as well as at his solo exhibition entitled Free Roses at Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art with an installation entitled "A Season in He'll". [10]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Mathieu, Bertrand, "Introduction" in Rimbaud, Arthur, and Mathieu, Bertrand (translator), A Season in Hell & Illuminations (Rochester, New York: BOA Editions, 1991).

- ↑ Bonnefoy, Yves: Rimbaud par lui-meme, Paris 1961, Éditions du Seuil

- ↑ Robb 2000, p. 201

- ↑ Arthur Rimbaud: Une Saison en Enfer/Eine Zeit in der Hölle, Reclam, Stuttgart 1970; afterword by W. Dürrson, p. 105.

- ↑ Arthur Rimbaud: Une Saison en Enfer/Eine Zeit in der Hölle, Reclam, Stuttgart 1970; afterword by W. Dürrson, S. 106.

- ↑ Fowlie, Wallace. Rimbaud: Complete Works, Selected Letters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966.

- ↑ Drachman, Steven S. (2011). The Ghosts of Watt O'Hugh. Chickadee Prince Books. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-578-08590-6.

- ↑ Galloway, Gregory (2005). As Simple As Snow. Putnam,.

- ↑ "Review, The Ghosts of Watt O'Hugh". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ "Designer detritus: artist Alex Da Corte makes the everyday extraordinary". Wallpaper. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

Bibliography

- Robb, Graham (2000), Rimbaud, Picador, ISBN 0-330-48803-1

External links

- Une Saison en enfer at abardel.free.fr (in French)

- Drafts of Une Saison at abardel.free.fr (in French)

- English translation