AFS Intercultural Programs

| |

| Formation | 1915 |

|---|---|

| Focus | Intercultural learning |

| Headquarters | New York City, New York, United States of America |

Region | Global |

| Method | International exchange programs |

Volunteers (2015) | 40,000[1] |

| Website |

afs |

AFS Intercultural Programs (or AFS, originally the American Field Service) is an international youth exchange organization. It consists of over 50 independent, not-for-profit organizations, each with its own network of volunteers, professionally staffed offices, volunteer board of directors and website. In 2015, 12,578 students traveled abroad on an AFS cultural exchange program, between 99 countries.[1] The U.S.-based partner, AFS-USA, sends more than 1,100 U.S. students abroad and places international students with more than 2,300 U.S. families each year. More than 424,000 people have gone abroad with AFS and over 100,000 former AFS students live in the U.S.[2]

History

WWI

When war broke out in 1914, the American Colony of Paris organized an "ambulance"[3]—the French term for a temporary military hospital—just as it had done in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 when the "American Ambulance" had been under tents set up near the Paris home of its founder, the celebrated Paris-American dentist, Dr. Thomas W. Evans.[4] The "American Ambulance" of 1914 took over the premises of the unfinished Lycée Pasteur in the suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine—and was run by the nearby American Hospital of Paris.

The volunteer drivers of 1914 found themselves behind the wheels of motorized, not horse-driven, vehicles: Model-Ts, purchased from the nearby Ford plant in Levallois-Perret.

In the fall of 1914, when the war front moved away from Paris, the American Ambulance set up an outpost in Juilly and sent out detached units of volunteer drivers to serve informally with the British and Belgian armies in the north.[5] In early 1915, one of those drivers, A. Piatt Andrew, was appointed “Inspector of Ambulances” by Robert Bacon, head of the American Ambulance and one of Andrew's colleagues from the Taft Administration.

The newly appointed inspector toured the ambulance sections of Northern France and learned that the American volunteers were bored with so-called "jitney work," transporting wounded soldiers from railheads to hospitals far back from the front lines. French army policy prohibited foreign nationals from traveling into battle zones.[6]

In March 1915, Andrew met with Captain Aime Doumenc, head of the French Army Automobile Service and pleaded his case for the American volunteers. They desired above all, he said, "to pick up the wounded from the front lines…, to look danger squarely in the face; in a word, to mingle with the soldiers of France and to share their fate!"[7] Doumenc agreed to give Andrew a trial. The success of Section Z was immediate and overwhelming, and by April 15, 1915, the French created American Ambulance Field Service operating under French Army command.[8][9]

This marked the formal beginning of American Ambulance Field Service, three units of which made their mark during battles in northern France, the Champagne, Verdun and the Vosges.[10]

By the summer of 1916, the Field Service severed its ties with the American Ambulance and moved its operations from cramped quarters in Neuilly to Paris, onto the spacious grounds of the Delessert château at 21 rue Raynouard in the Passy area of Paris.[11] There, it grew rapidly over the next year, continuing to provide "sanitary sections" to the French Army, while also serving as a recruitment source of combat pilots for the newly formed Escadrille Lafayette,[12] one of whose prime movers, Dr. Edmund L. Gros, was the Field Service’s in-house physician.

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, the French Army successfully appealed to the Field Service for drivers for its military transport sections[13] —and so, no longer limited to medical transport, the organization renamed itself the “American Field Service”, thus establishing today’s well-known acronym, “AFS”.

Before the AFS was absorbed into the much larger, federalized U.S. Army Ambulance Service,[14] it had numbered more than 2500 volunteers, including some 800 drivers of French military transport trucks. It had actively recruited its drivers from the campuses of American colleges and universities, promoting morale by creating units with volunteers from the same schools. All financed their own uniforms and transportation to France where they worked under the same conditions as French ambulance drivers—with the same pay—and often found themselves serving under extremely dangerous missions on the Front. By the end of the war, some 127 men who had served with the AFS were killed and a notable number of individuals and units earned the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille de Guerre for their heroic actions as drivers.[15]

Other volunteer ambulance corps served the French Army as “foreign sanitary sections” during World War I. The first was Henry Harjes’ “Formation” units under the American Red Cross,[16] followed by Richard Norton’s American Volunteer Motor-Ambulance Corps,[17] organized in London under the St. John’s Ambulance (the British Red Cross). Later, both would merge —under the American Red Cross—as the “Norton-Harjes”. In the summer and fall of 1917, when all the volunteer ambulance services were invited to join the new U.S. Army Ambulance Service, Norton’s units simply disbanded, while Harjes’, under the American Red Cross, moved into Italy where they would subsequently serve under the USAAS.

Once the Americans entered the war, many drivers joined combat units, both French and American, serving as officers in a variety of assignments, notably in air force and artillery units. At the same time, a large percentage of volunteers signed up for the military, thenceforth members of USAAS units, but remaining identified with their AFS past—a past kept alive through the work of HQ, still at 21 rue Raynouard, where a Bulletin[18] was published and where visiting ambulance drivers could find temporary lodgings and meals.

WWI Publications

The young AFS drivers came from "prominent families in the States," and had attended, or were still attending, one of almost a hundred prominent colleges or universities around the country. Also represented were a smaller group from America's professional class: doctors, lawyers, architects, painters, brokers, businessmen, poets and writers.[19][20][21] This literate group produced many letters, diaries, journals, and even poetry. The AFS collected many of these writings into Friends of France, published in 1916. The Service used this volume to recruit more volunteers to the "gloriously exciting and grandly humanitarian" work of an ambulancier on the Western Front.[22]

Also published in 1916, Ambulance Number 10, by Leslie Buswell, was composed of the author's letters back to the States. Buswell went on to assist Henry Sleeper in the AFS's recruiting and fundraising offices in Boston.

Other literary "ambulanciers" brought their letters and journals and memoirs to American publishers in the coming years. William Yorke Stevenson produced To The Front in a Flivver in 1917, stayed on in France after militarization, and composed From "Poilu" to "Yank" in 1918.[23][24] Robert Imbrie published Behind the Wheel of a War Ambulance in 1918, as did Julien Bryan with Ambulance 464: Encore des Blesses[25][26]

The AFS recruits who joined the Service in late spring 1917, after Congress's declaration of war, were greeted by Piatt Andrew with a request: Would they forego ambulance driving for trucking supplies to the front? Eight hundred AFS recruits joined the camion service, including John Kautz, who published Trucking to the Trenches in 1918.[27]

After the war the Field Service produced three hefty volumes of writings from numerous AFS alumni, including excerpts from the previously published books above.[28]

Between the wars

Following the Great War, the AFS became sponsors for the French Fellowships[29]—graduate student scholarships for study in France and in the US—which were ultimately administered by the Institute of International Education and were precedents for the Fulbright Foundation exchanges. AFS also created an association for its veterans, publishing a bulletin,[30] organizing reunions and contributing a wing to house its memorabilia at the Museum of Franco-American Cooperation in Blérancourt, France.[31]

WWII

When World War II broke out, AFS reorganized its ambulance service,[32] sending units first to France and then to the British Armies in North Africa, Italy, India-Burma and with the Free French for the final drive from southern France to Germany.

Postwar

In September 1946, Stephen Galatti,[33] president of AFS, established the American Field Service International Scholarships. During the 1947-48 school year, the first students came from ten countries including Czechoslovakia, Estonia, France, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway and Syria.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Modern day

As of 2014, there are over 55 AFS organizations worldwide serving over 80 different countries, providing exchange opportunities for over 13,000 students and teachers annually.

AFS is one of the largest volunteer-based organizations of its kind in the world with more than 440,000 volunteers worldwide and more than 5,000 in the U.S. Tens of thousands of volunteers and a small staff make the AFS program happen worldwide. AFS volunteers are both young and old, busy professionals and retirees, and students and teachers. AFS provides development and training opportunities for volunteers.

AFS volunteers help in many areas including facilitating the AFS mission in the local community and schools by finding and interviewing students and families. Further involvement includes serving as a contact person for an AFS student, organizing fund raising events, and arranging activities for AFS students. As a volunteer-driven organization, AFS depends on donations of time to implement and monitor the delivery of programs.

Notable exception in the AFS network is its presence in China. Here AFS offers an outbound long-term student exchange program since 1997 and an inbound program since 2001. These programs however, are run and administrated by the China Education Association for International Exchange (CEAIE), an organization focusing on teacher exchanges that was founded by the Chinese Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Education.[34]

Statement of purpose

AFS is an international, voluntary, non-governmental, non-profit organization that provides intercultural learning opportunities to help people develop the knowledge, skills and understanding needed to create a more just and peaceful world.[35]

Notable AFS Ambulance Corps volunteers

- William Seabrook

- Julien Bryan

- Preston M. Burch

- Malcolm Cowley

- Harry Crosby

- Ward Chamberlin

- Patrick Dennis

- Sidney Howard

- John Howard Lawson

- J. Roderick MacArthur

- Waldo Peirce

- Bayard Tuckerman, Jr.

- Tom Cole

Notable AFS exchange students

- Edgar Ramirez, Venezuelan actor (went to Austria)

- Lee Bollinger, the 19th president of Columbia University (went to Brazil)

- Luca Parmitano, Italian astronaut (went to US)

- Catherine Coleman, American astronaut (went to Norway)

- Anies Baswedan, Indonesian Minister of Education and Culture (went to USA 1987-1988)

- Dixie Dansercoer, Belgian explorer (went to the US)

- John Deighton, Harvard Business School Professor (went to USA from South Africa)

- Jan Eliasson, former President of the UN General Assembly and Swedish Minister of Foreign Affairs (went to the US), UN deputy secretary-general from July 1, 2012

- Cesar Gaviria, former President of Colombia (went to the US)

- Israel Hanukoglu, Professor of Biochemistry and Science adviser of the Israeli Prime Minister (went to the US)

- Yoshihiro Hattori (went to the US)

- Bill Irwin, American actor (went to Northern Ireland)

- Ernesto Jerez, a Dominican sportscaster

- Kenneth I. Juster, (went to Thailand)

- David Madden, American quiz show champion and founder of the International History Bee and Bowl (went to Austria)

- Zalmay Khalizad, former United States Ambassador to the United Nations (went to the US)

- Christine Lagarde, current IMF Director, former Minister of Economic Affairs, Industry and Employment of France (went to the US)

- Ulrike Lunacek, current Austrian member of the European Parliament (went to the US)

- Margaret H. Marshall, 23rd Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and the first female to hold that position (AFS to US from South Africa)

- Milow, a Belgian singer (went to the US)

- Jann Klose, German-born singer-songwriter (went to the US)

- Klaus Eberhartinger, Austrian singer and presenter (went to the US)

- Diana Muir, an American writer and historian (went to Chile)

- Tiina Nunnally, an American author and translator (went to Denmark)

- Helmut Panke, a member of the board of directors at Microsoft (went to the US)

- Gerhard Pfanzelter, Austrian Ambassador to the United Nations (went to the US)

- Nicole Rash, 2007 Miss Indiana (went to Bolivia)

- Lieven Scheire, Belgian comedian (went to Iceland)

- Yasuhisa Shiozaki, Japanese politician (went to the US)

- Linda Wells, American editor-in-chief (went to Turkey)

- Craig Wilson, American columnist (went to Great Britain)

- James Woolsey, a foreign policy specialist and former Director of Central Intelligence and head of the Central Intelligence Agency (February 5, 1993 - January 10, 1995) (went to Sweden)

- Colin Bundy Principal of Green Templeton College, Oxford (AFS to US from South Africa)

- J. Christopher Stevens, U.S. Ambassador to Libya killed while serving as US Ambassador to Libya (went to Spain)

- İsmail Cem İpekçi Turkish Foreign Minister went to USA

- Rogelio Pfirter, Argentinian Diplomat (went to the US)

- Susana Malcorra, United Nations Chef de Cabinet to the Executive Office, served as Chief Operating Officer and Deputy Executive Director of the World Food Programme (went to the US)

- Jorge Argüello, Argentinian Ambassador (went to the US)

- Julio Frade, Uruguayan Actor, Radio Announcer and Pianist (went to the US)

- Alfreð Finnbogason, Icelandic soccer player (went to Italy)

- Alfred Biolek, German entertainer (went to the US)

- Ron Underwood, American director (went to Sri Lanka, aka Ceylon)

- Torbjørn Røe Isaksen, Norwegian politician (went to the US)

- Ulrich Tukur, German actor (went to the US)

- Renata Sorrah, Brazilian actress (went to the US)

- Tim Noakes, an A-rated South African professor of exercise and sports science at the University of Cape Town (went to the US)

- Shamcey Supsup, Filipina, Miss Universe 2011 3rd runner-up.

- Diann Shipione, U.S. Financial Advisor and U.S. Municipal Pension System Advocate (went to Sri Lanka)[36]

AFS-USA, Inc.

AFS-USA, Inc. (a.k.a., AFS-USA) is the AFS partner organisation in the United States and is a registered 501(c)(3). Approximately 1,100 participants go abroad with AFS-USA annually. Over 2,300 international AFS students from AFS-USA partner countries are hosted in the U.S. annually. AFS-USA is supported by a volunteer base of over 5,000. Students aged 15 – 18 may partake in AFS-USA programs, while Gap Programs are available for individuals over 18 years of age on a gap year.

AFS-USA Public Diplomacy Initiatives

Public Diplomacy Initiatives at AFS-USA offer support for international students to study in the United States and for U.S. students to study abroad via full funded scholarships by grant-making foundations or by the Educational and Cultural Affairs Bureau of the U.S. Department of State.

Congress Bundestag

The Congress Bundestag Youth Exchange Program (CB) was launched in 1983 by the U.S. Congress and the German Parliament. AFS currently provides 50 merit-based, full scholarships for U.S. students and 60 scholarships for German participants.

National Security Language Initiative for Youth (NSLI-Y)

The National Security Language Initiative for Youth (NSLI-Y) program is part of a broader government-wide presidential initiative that prepares American citizens to be leaders in a global world. Now more than ever, it is important that Americans have the necessary linguistic skills and cultural knowledge to promote international dialogues, support American engagement abroad, and attain better understanding of global cultures and issues. NSLI-Y encourages a lifetime of language study and cultural understanding by providing approximately 600 fully funded scholarships to American high school students.

In 2012, NSLI-Y offers academic scholarships to learn Arabic, Chinese, Hindi, Korean, Persian (Tajik), Russian, and Turkish through summer and year-long programs in China, Morocco, Oman, Jordan, India, Korea, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkey, and other countries around the world.[37]

Future Leaders Exchange (FLEX)

The Future Leaders Exchange (FLEX) program originated in the FREEDOM Support Act, which was sponsored by U.S. Senator Bill Bradley and was passed by Congress in 1992. FLEX provides full merit-based scholarships to students from the countries of the former Soviet Union.

Kennedy-Lugar Youth Exchange and Study (YES)

Kennedy-Lugar Youth Exchange and Study (YES) was initiated by The Department of State in the aftermath of Sept. 11. It aims to build bridges of understanding between Americans and people in countries with significant Muslim populations.

AFS-USA Scholarships

AFS-USA awards more than $3 million in financial aid and scholarships to students each year. More than 40% of AFS-USA participants receive some form of financial assistance each year either need-based, merit-based or both. A partial list of scholarships and financial aid:

- Global Leaders is the primary AFS scholarship program, offering partial need and merit-based scholarships to qualified applicants.

- Faces of America is AFS-USA’s signature diversity program and makes it possible for high school students from underserved communities to receive scholarship awards to study abroad in more than 23 countries around the world.

- AFS Family Scholarships are awards are given to applicants who are former host family members, returnees, children of returnees, and of descendants of AFS Ambulance Drivers.

- The Yoshi Hattori Memorial Scholarship is a merit-based scholarship is designed to promote intercultural understanding and peace, and was created in memory of Yoshi Hattori, an AFS Exchange Student to the U.S. from Japan.

- The Toshiyuki Tanaka American Embassy Scholarship is a need-based and merit-based scholarship awarded through the Pacific Affairs Section (PAS) of the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo and the generosity of Mr. Toshiyuki Tanaka.

References

- 1 2 "2015 AFS Annual Report". AFS Intercultural Programs. 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ↑ About AFS

- ↑ Col. T. Bentley Mott. Myron Herrick. Friend of France. An Autobiographical Biography. Garden City, New York. Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1929

- ↑ Thomas W. Evans, History of the American Ambulance Established in Paris during the Siege of 1870-71, London: Low, Low and Searle, 1873.

- ↑ J. Paulding Brown. "The First Months of the American Ambulance (September 1914 to May 1915),”; in George Rock History of the American Field Service, 1920-1955

- ↑ Hansen, Arlen (1996, 2011). Gentlemen Volunteers. Arcade Publishing. p. 14

- ↑ Hansen, Arlen (1996, 2011). Gentlemen Volunteers. Arcade Publishing. p. 44

- ↑ A. Piatt Andrew. Letters Written Home from France in the First Half of 1915. Privately printed, 1915

- ↑ .Official Document

- ↑ Stephen Galatti, "The Growth of the Service" in History of the American Field Service in France. "Friends of France". 1914-1917. Told by its Members with Illustrations. Boston and New York. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920.

- ↑ “21”

- ↑ Flying Corps

- ↑ Mallet Reserve Bulletin

- ↑ John R. Smucker, Jr. The United States Army Ambulance Service in Armies of France and Italy, 1917-1918-1919, USAAS Association. 1967.

- ↑ “Decorations” in History of the American Field Service in France. “Friends of France”. 1914-1917. Told by its Members with Illustrations. Boston and New York. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920.

- ↑ The Harjes Formation

- ↑ William Fenwick Harris. “Richard Norton, 1872-1918” in Harvard Graduates' Magazine, December 1918.

- ↑ The American Field Service Bulletins, published at 21, rue Raynouard, Paris, 1917-1919.

- ↑ Friends of France: the Field Service of the American Ambulance described by its members. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916, p. 63

- ↑ History of the American Field Service in France, as told by its members, vol. 3. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1920, p. 440.

- ↑ History of the American Field Service in France, as told by its members, vol. 1. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1920, p. 7.

- ↑ Hansen, Arlen (1996, 2011). Gentlemen Volunteers. Arcade Publishing. p. 39-40.

- ↑ Stevenson, William Yorke. To the Front in a Flivver. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1917.

- ↑ Stevenson, William Yorke. From "Poilu" to "Yank." Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1918.

- ↑ Imbrie, Robert Whitney. Behind the Wheel of a War Ambulance. NY: Robert McBride and Co., 1918.

- ↑ Bryan, Julien H. Ambulance 464: Encore des Blesses. NY: Macmillan Co., 1918.

- ↑ John Iden Kautz, Trucking to the Trenches: Letters from France, June–November, 1917. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1918

- ↑ History of the American Field Service in France, as told by its members, vols. 1-3, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1920.

- ↑ George Rock. ”Between the Wars: The Fellowships for French Universities” in History of the American Field Service, 1920-1955. New York, 1956.

- ↑ American Field Service Association Bulletins, 1920-1935

- ↑ The Museum of Franco-American Cooperation at Blérancourt

- ↑ George Rock. History of the American Field Service, 1920-1955. New York, 1956.

- ↑ About Stephen Galatti

- ↑ AFS Schüleraustausch mit China URL: "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-16. Retrieved 2011-08-10. (Stand 9.März 2005)

- ↑ About AFS Intercultural Programs

- ↑ "Plan Foreign Study". Tucson Daily Citizen. 1969-06-11.

- ↑ "Languages and Programs". www.nsliforyouth.org.

- "Friends of France: the Field Service of the American Ambulance," described by its members. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916.

- "History of the American Field Service in France," as told by its members, vols. 1-3, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1920.

- Hansen, Arlen. "Gentlemen Volunteers." NY: Arcade Publishing, 1996, 2011.

- Bryan, Julien H. "Ambulance 464: Encore des Blesses." NY: Macmillan Co., 1918.

- Leslie Buswell. "Ambulance No. 10: Personal Letters from the Front." NY: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1916.

- Imbrie, Robert Whitney. "Behind the Wheel of a War Ambulance." NY: Robert McBride and Co., 1918.

- Kautz, John Iden. Trucking to the Trenches: Letters from France, June-November, 1917. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1918.

- Stevenson, William Yorke. To the Front in a Flivver. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1917.

- Stevenson, William Yorke. From "Poilu" to "Yank". Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1918.

External links

- Official website

- European Federation for Intercultural Learning

- Video interview of AFS students in INDIA, Ludovica Fois & Sophia Mersmann

- Our Story

- AFS in WWI - Digital Collection

- AFS in the Hospitality Club

- National Security Language Initiative for Youth (NSLI-Y) program site

- AFS Yogyakarta Indonesia | Bina Antarbudaya Chapter Yogyakarta

- American Field Service Driver, by Larry W. Roeder, Amazon, 2012

Official AFS websites

-

AFS Argentina official website

AFS Argentina official website -

AFS Australia official website

AFS Australia official website -

AFS Austria official website

AFS Austria official website -

.svg.png) AFS Belgium Flanders official website

AFS Belgium Flanders official website -

.svg.png) AFS Belgium French official website

AFS Belgium French official website -

AFS Bolivia official website

AFS Bolivia official website -

AFS Bosnia and Herzegovina official website

AFS Bosnia and Herzegovina official website -

AFS Brazil official website

AFS Brazil official website -

AFS Canada official website

AFS Canada official website -

AFS Chile official website

AFS Chile official website -

AFS China official website

AFS China official website -

AFS Colombia official website

AFS Colombia official website -

AFS Costa Rica official website

AFS Costa Rica official website -

AFS Czech Republic official website

AFS Czech Republic official website -

AFS Denmark official website

AFS Denmark official website -

AFS Dominican Republic official website

AFS Dominican Republic official website -

AFS Ecuador official website

AFS Ecuador official website -

AFS Egypt official website

AFS Egypt official website -

AFS European Federation For Intercultural Learning official website

AFS European Federation For Intercultural Learning official website -

AFS Finland official website

AFS Finland official website -

AFS France official website

AFS France official website -

AFS Germany official website

AFS Germany official website -

AFS Ghana official website

AFS Ghana official website -

AFS Guatemala official website

AFS Guatemala official website -

AFS Honduras official website

AFS Honduras official website -

AFS Hong Kong official website

AFS Hong Kong official website -

AFS Hungary official website

AFS Hungary official website -

AFS Iceland official website

AFS Iceland official website -

AFS India official website

AFS India official website -

AFS Indonesia official website

AFS Indonesia official website -

AFS Yogyakarta Indonesia official website

AFS Yogyakarta Indonesia official website -

Intercultura (AFS Italy) official website

Intercultura (AFS Italy) official website -

AFS Japan official website

AFS Japan official website -

AFS Latvia official website

AFS Latvia official website -

AFS Malaysia official website

AFS Malaysia official website -

AFS Mexico official website

AFS Mexico official website -

AFS Netherlands official website

AFS Netherlands official website -

AFS New Zealand official website

AFS New Zealand official website -

AFS Norway official website

AFS Norway official website -

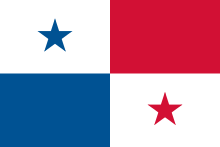

AFS Panama official website

AFS Panama official website -

AFS Paraguay official website

AFS Paraguay official website -

AFS Peru official website

AFS Peru official website -

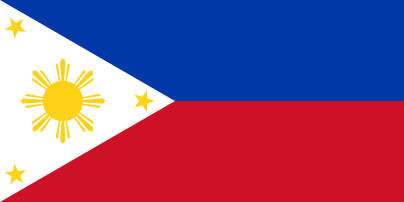

AFS Philippines official website

AFS Philippines official website -

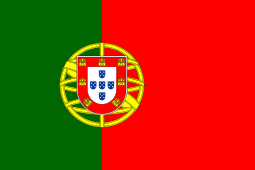

AFS Portugal official website

AFS Portugal official website -

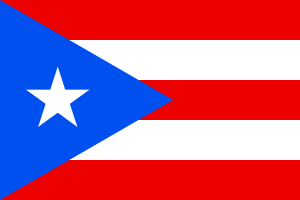

AFS Puerto Rico official website

AFS Puerto Rico official website -

AFS Russia official website

AFS Russia official website -

AFS Serbia official website

AFS Serbia official website -

AFS Slovakia official website

AFS Slovakia official website -

AFS South Africa official website

AFS South Africa official website -

AFS Spain official website

AFS Spain official website -

AFS Sweden official website

AFS Sweden official website -

AFS Switzerland official website

AFS Switzerland official website -

AFS Thailand official website

AFS Thailand official website -

AFS Tunisia official website

AFS Tunisia official website -

AFS Turkey official website

AFS Turkey official website -

AFS Uruguay official website

AFS Uruguay official website -

AFS USA official website

AFS USA official website -

AFS Venezuela official website

AFS Venezuela official website

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to American Field Service - AFS Intercultural Programs. |