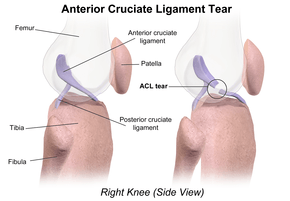

Anterior cruciate ligament injury

| Anterior cruciate ligament injury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diagram of the right knee | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | A "pop" with pain, knee instability, swelling of knee[1] |

| Causes | Non-contact injury, contact injury[2] |

| Risk factors | Athletes, female[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Physical exam, MRI[1] |

| Prevention | Neuromuscular training,[3] core strengthening[4] |

| Treatment | Braces, physical therapy, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | ~200,000 per year (US)[2] |

Anterior cruciate ligament injury is when the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is either stretched, partially torn, or completely torn.[1] Injuries are most commonly complete tears.[1] Symptoms include pain, a popping sound during injury, instability of the knee, and joint swelling.[1] Swelling generally appears within a couple of hours.[2] In approximately 50% of cases other structures of the knee such as ligaments, cartilage, or meniscus are damaged.[1]

The underlying mechanism often involves a rapid change in direction, sudden stop, landing following jumping, or direct contact.[1] It is more common in athletes, particularly those who are involved in recreational alpine skiing, play soccer, football, or basketball.[1][5] Diagnosis is typically by physical examination and maybe support by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[1]

Prevention is by neuromuscular training and core strengthening.[3][4] Treatment recommends depend on desired level of activity. If there will be low levels of future activity bracing and physiotherapy may be sufficient.[1] In those with high activity levels arthroscopic repair via anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is often recommended.[1] Surgery, if recommended, is generally not carried out until the initial inflammation from the injury has resolved.[1]

As of 2009 about 200,000 people are affected per year in the United States.[2] In some sports females have a higher risk while in others both sexes are equally affected.[5] Without surgery, in those with a complete tear, many are unable to play sports and develop osteoarthritis.[2]

Signs and symptoms

An individual may feel or hear a "pop" in their knee during a twisting movement[6] or rapid deceleration, followed by an inability to continue participation in the sport and early swelling from hemarthrosis. This combination is said to indicate a 90% probability of rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament.[7] An individual may experience instability in the knee once they resume walking and other activities, and they may feel their knee is "giving out".

Risk factors

ACL injury is most commonly a non-contact injury that occurs when an individual stops suddenly or plants his or her foot hard into the ground (cutting). ACL injury also has been linked to heavy or stiff-legged landing; the knee rotating while landing, especially when the knee is in an unnatural position.

Significantly, many ACL injuries occur in athletes landing flat on their heels. This movement directs the forces directly up the tibia into the knee, while the straight-knee position places the anterior femoral condyle on the back-slanted portion of the tibia. The resultant forward slide of the tibia relative to the femur is restrained primarily by the now-vulnerable ACL.

ACL injuries also can be caused by direct contact or trauma, such as in a motor vehicle collision or from a tackle in football. A severe form of ACL injury caused by direct contact is called the "unhappy triad," also known as the "terrible triad," or "O'Donaghue's triad." The "unhappy triad" involves injury of the anterior cruciate ligament, the medial collateral ligament, and the medial meniscus.[8]

Sex-related differences

Women in sports such as association football, basketball, and tennis are significantly more prone to ACL injuries than men. The discrepancy has been attributed to gender differences in anatomy, general muscular strength, reaction time of muscle contraction and coordination, and training techniques.

Gender differences in ACL injury rates become evident when specific sports are compared.[9] A review of NCAA data has found relative rates of injury per 1000 athlete exposures as follows:

- Men's basketball 0.07, women's basketball 0.23

- Men's lacrosse 0.12, women's lacrosse 0.17

- Men's football 0.09, women's football 0.28

The highest rate of ACL injury in women occurred in gymnastics, with a rate of injury per 1000 athlete exposures of 0.33 Of the four sports with the highest ACL injury rates, three were women's – gymnastics, basketball and soccer.[10]

According to recent studies, female athletes are two to eight times more likely to strain their anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in sports that involve cutting and jumping as compared to men who play the same particular sports (soccer, basketball, and volleyball).[11] Differences between males and females identified as potential causes are the active muscular protection of the knee joint, the greater Q angle putting more medial torque on the knee joint, relative ligament laxity caused by differences in hormonal activity from estrogen and relaxin, intercondylar notch dimensions, and muscular strength.[11][12]

Hormonal and anatomic differences

Before puberty, there is no observed difference in frequency of ACL tears between the sexes. Changes in sex hormone levels, specifically elevated levels of estrogen and relaxin in females during the menstrual cycle, have been hypothesized as causing predisposition of ACL ruptures. This is because they may increase joint laxity and extensibility of the soft tissues surrounding the knee joint.[11] Additionally, female pelvises widen during puberty through the influence of sex hormones. This wider pelvis requires the femur to angle toward the knees. This angle towards the knee is referred to as the Q angle. The average Q angle for men is 14 degrees and the average for women is 17 degrees. Steps can be taken to reduce this Q angle, such as using orthotics.[13] The relatively wider female hip and widened Q angle may lead to an increased likelihood of ACL tears in women.

ACL, muscular stiffness, and strength

During puberty, sex hormones also affect the remodeled shape of soft tissues throughout the body. The tissue remodeling results in female ACLs that are smaller and will fail (i.e. tear) at lower loading forces, and differences in ligament and muscular stiffness between men and women. Women’s knees are less stiff than men’s during muscle activation. Force applied to a less stiff knee is more likely to result in ACL tears.[14]

In addition, the quadriceps femoris muscle is an antagonist to the ACL. According to a study done on female athletes at the University of Michigan, 31% of female athletes recruited the quadriceps femoris muscle first as compared to 17% in males. Because of the elevated contraction of the quadriceps femoris muscle during physical activity, an increased strain is placed onto the ACL due to the "tibial translation anteriorly".[15]

Ligament dominance

The increased risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury among female athletes is best predicted by the motion and loading of the knee during performance situations.[16] The ligament dominance theory suggests that females typically perform athletic movements with greater knee valgus angles. A greater amount of stress is placed on the ACL in these situations because there is high activation of the quadriceps muscles despite limited knee flexion, limited hip flexion, greater hip adduction, and a large knee adductor moment.[17][18] Additionally, females typically land with their tibia rotated internally or externally.[19] As a result of increased knee valgus stress, ground reaction forces are greater and laterally directed.[20]

Quadriceps dominance

Ligament dominance is observed when there is excessive movement in the frontal plane to accommodate limited movement in the sagittal plane. This is caused by weakness in the hamstring muscles or reliance on the strength of the quadriceps muscles.[18] This quadriceps dominance theory identifies when the hamstring muscles are notably weaker than the quadriceps muscles. As a result, knee stability in performance situations depends on the quadriceps due to a discrepancy in the pattern in recruiting quadriceps and hamstring muscles.[21]

Trunk and leg dominance

Other theories used to explain the increased risk of ACL injury among female athletes include the trunk dominance and leg dominance theories. Trunk dominance suggests that males typically exhibit greater control of the trunk in performance situations as evidenced by greater activation of the internal oblique muscle. Leg dominance suggests that females exhibit greater kinematic leg asymmetry in knee valgus angles, hip abduction, and ankle abduction in performance situations.[17]

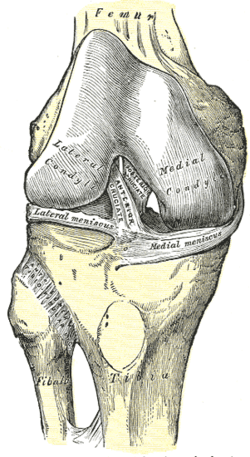

|

|

| Right knee, front, showing interior ligaments | Left knee, behind, showing interior ligaments |

Diagnosis

Manual tests

The pivot-shift test, anterior drawer test, and Lachman test are used during the clinical examination of suspected ACL injury. The Lachman test is recognized by most authorities as the most reliable and sensitive test, and usually superior to the anterior drawer test.[22]

An ACL tear can present with a popping sound heard after impact, swelling after a couple of hours, severe pain when bending the knee, and buckling or locking of the knee during movement.

Though clinical examination in experienced hands can be accurate, the diagnosis is usually confirmed by using an arthrometer or MRI, which have greatly lessened the need for diagnostic arthroscopy and which have a higher accuracy than clinical examination. It may also permit visualization of other structures which may have been coincidentally involved, such as a meniscus, or collateral ligament, or posterolateral corner of the knee joint.

Laximetry

Laximetry is a reliable technique for diagnosing a torn anterior cruciate ligament.[23]

MRI scan

The MRI is perhaps the most used technique for diagnosing the state of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament but it not always the most reliable. In some cases the Anterior Cruciate Ligament can indeed not be seen because of the blood surrounding it.

Prevention

Interest in reducing non-contact ACL injury has been intense and the observed, increased, liability of the female gender in some sports has added to this. The International Olympic Committee, after a comprehensive review of preventive strategies, has stated that injury prevention programs have an effect on reducing injuries that is measurable, and that applies particularly to women.[24] Further, paying attention to the balance of strength between hamstrings and quadriceps will help prevent the anterior cruciate ligament from being overpowered by over-emphasized quadriceps strength. It is also stressed that landing forces should be reduced together with emphasizing proper landing technique. It has been previously reported that landing on the heel, rather than forefoot with progressive transfer of weight to the heel, is potentially injurious to the ACL because of the hyperextension forces created. The closer the knee is to full extension, the more likely this is to occur.[25]

Accordingly, it is generally recommended that injury prevention programs stress these principles.

Treatment

The term for non-surgical treatment for ACL rupture is "conservative management", and it often includes physical therapy and using a knee brace. Instability associated with ACL deficiency increases the risk of other knee injuries such as a torn meniscus, so sports with cutting and twisting motions are problematic and surgery is often recommended in those circumstances.

Patients who have suffered an ACL injury should be evaluated for other injuries that often occur in combination with an ACL tear and include cartilage/meniscus injuries, bone bruises, PCL tears, posterolateral injuries and collateral ligament injuries.

Conservative

A torn ACL is less likely to restrict the movement of the knee. When tears to the ACL are not repaired it can sometimes cause damage to the cartilage inside the knee because with the torn ACL the tibia and femur bone are more likely to rub against each other. Immediately after the tear of the ACL, the person should rest the knee, ice it every 15 to 20 minutes, provide compression on the knee, and then elevate above the heart; this process helps decrease the swelling and reduce the pain. The form of treatment is determined based on the severity of the tear on the ligament. Small tears in the ACL may just require several months of rehab in order to strengthen the surrounding muscles, the hamstring and the quadriceps, so that these muscles can compensate for the torn ligament. Falls associated with knee instability may require the use of a specific brace to stabilize the knee. Women are more likely to experience falls associated with the knee giving way. Sudden falls can be associated with further complications such as fractures and head injury.

Surgery

If surgery is decided upon, either because obvious instability interferes with activities of daily living, or because the knee is subject to repeated, severe, provocative maneuvers, such as the case of the competitive athlete involved in cutting and rapid deceleration etc., then several issues need to be decided upon.

- Timing. Immediate repair is usually avoided and initial swelling and inflammatory reaction allowed to subside.

- Choice of graft material, autograft or allograft.

- Choice of anterior cruciate ligament augmentation, patellar tendon or hamstring tendon.[26]

These issues are fully explored in ACL Reconstruction.

Epidemiology

There are around 200,000 ACL tears each year in the United States, with over 100,000 ACL reconstruction surgeries per year. Over 95% of ACL reconstructions are performed in the outpatient setting. The most common procedures performed during ACL reconstruction are partial meniscectomy and chondroplasty.[27]

Special populations

Young athletes

High school athletes are at increased risk for ACL tears when compared to non-athletes. This risk increases with certain types of sports. Among high school girls, the sport with the highest risk of ACL tear is soccer, followed by basketball and lacrosse. The highest risk sport for boys was basketball, followed by lacrosse and soccer.[28] Children and young athletes may benefit from early surgical reconstruction after ACL injury. Young athletes who have early surgical reconstruction of their torn ACL are more likely to return to their previous level of athletic ability when compared to those who underwent delayed surgery or nonoperative treatment. They are also less likely to experience instability in their knee if the undergo early surgery.[29]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries-OrthoInfo - AAOS". orthoinfo.aaos.org. March 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "ACL Injury: Does It Require Surgery?-OrthoInfo - AAOS". orthoinfo.aaos.org. September 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- 1 2 Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD. "Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 2, a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention.". Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):490. 34: 490–8. PMID 16382007. doi:10.1177/0363546505282619.

- 1 2 Sugimoto D, Myer GD, Foss KD, Hewett TE. "Specific exercise effects of preventive neuromuscular training intervention on anterior cruciate ligament injury risk reduction in young females: meta-analysis and subgroup analysis.". Br J Sports Med. 49: 282–9. PMID 25452612. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093461.

- 1 2 Prodromos CC, Han Y, Rogowski J, Joyce B, Shi K (Dec 2007). "A meta-analysis of the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears as a function of gender, sport, and a knee injury-reduction regimen". Arthroscopy. 23 (12): 1320–25. PMID 18063176. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.003.

- ↑ "ACL Reconstruction Sydney NSW | ACL Injury Treatment Sydney NSW". Dr Stephen Rimmer | Sydney Orthopedic Knee Surgeon. 2016-10-16. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Bytomski J, Moorman C (2010). Oxford American Handbook of Sports Medicine. Oxford American Handbook of Medicine Series (First ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 290. ISBN 9780195372199.

- ↑ O'donoghue, D. H. (1950-10-01). "Surgical treatment of fresh injuries to the major ligaments of the knee". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 32 A (4): 721–738. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 14784482.

- ↑ Mountcastle SB, Posner M, Kragh JF, Taylor DC (October 2007). "Gender differences in anterior cruciate ligament injury vary with activity: epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in a young, athletic population". Am J Sports Med. 35 (10): 1635–42. PMID 17519438. doi:10.1177/0363546507302917.

- ↑ Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J (Apr–Jun 2007). "Epidemiology of Collegiate Injuries for 15 Sports: Summary and Recommendations for Injury Prevention Initiatives". J Athl Train. 42 (2): 311–19. PMC 1941297

. PMID 17710181.

. PMID 17710181. - 1 2 3 Faryniarz, Deborah A.; Bhargava, Madhu; Lajam, Claudette; Attia, Erik T.; Hannafin, Jo A. (2006-07-01). "Quantitation of Estrogen Receptors and Relaxin Binding in Human Anterior Cruciate Ligament Fibroblasts". In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. Animal. 42 (7): 176–181. JSTOR 4295693.

- ↑ Wojyts Edward M.; Huston Laura J.; Schock Harold J.; Boylan James P.; Ashton-Miller James A. (2003). "GENDER DIFFERENCES IN MUSCULAR PROTECTION OF THE KNEE IN TORSION IN SIZE-MATCHED ATHLETES". Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 85 (5): 782.

- ↑ McLean SG, Huang X, van den Bogert AJ (2005). "Association between lower extremity posture at contact and peak when the tibia moves too far forward implications for ACL injury". Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 20 (8): 863–70. PMID 16005555. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.05.007.

- ↑ Slauterbeck, JR; Hickox JR; Beynnon B; Hardy DM (2006). "Anterior Cruciate Ligament Biology andIts Relationship to Injury Forces". Orthop Clin N Am. 37: 585–591. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2006.09.001.

- ↑ Biondino, Robert (November 1999). "Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes". Connecticut Medicine. 63 (11): 657–660. PMID 10589146.

- ↑ Hewett T. E.; Myer G. D.; Ford K. R.; Heidt R. S.; Colosimo A. J.; McLean S. G.; den Bogert A. J.; Paterno M. V.; Succop P. (2005). "Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 33 (4): 492–501. doi:10.1177/0363546504269591.

- 1 2 Pappas E.; Carpes F. P. (2012). "Lower extremity kinematic asymmetry in male and female athletes performing jump-landing tasks". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 15 (1): 87–92. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2011.07.008.

- 1 2 Pollard C. D.; Sigward S. M.; Powers C. M. (2010). "Limited hip and knee flexion during landing is associated with increased frontal plane knee motion and moments". Clinical Biomechanics. 25 (2): 142–146. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.10.005.

- ↑ Nagano Y.; Ida H.; Akai M.; Fukubayashi T. (2007). "Gender differences in knee kinematics and muscle activity during single limb drop landing". The Knee. 14 (3): 218–223. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2006.11.008.

- ↑ Sigward S. M.; Powers C. M. (2007). "Loading characteristics of females exhibiting excessive valgus moments during cutting". Clinical Biomechanics. 22 (7): 827–833. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.04.003.

- ↑ Ford K. R.; Myer G. D.; Hewett T. E. (2003). "Valgus knee motion during landing in high school female and male basketball players". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 31 (10): 1745–1750.

- ↑ van Eck CF, van den Bekerom MP, Fu FH, Poolman RW, Kerkhoffs GM (Aug 2013). "Methods to diagnose acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis of physical examinations with and without anaesthesia". Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 21 (8): 1895–903. PMID 23085822. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-2250-9.

- ↑ Rohman, Eric M.; Macalena, Jeffrey A. (2016-03-16). "Anterior cruciate ligament assessment using arthrometry and stress imaging". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 9 (2): 130–138. ISSN 1935-973X. PMC 4896874

. PMID 26984335. doi:10.1007/s12178-016-9331-1.

. PMID 26984335. doi:10.1007/s12178-016-9331-1. - ↑ P Renstrom; A Ljungqvist; E Arendt; B Beynnon; T Fukubayashi; W Garrett; T Georgoulis; T E Hewett; R Johnson; T Krosshaug; B Mandelbaum; L Micheli; G Myklebust; E Roos; H Roos; P Schamasch; S Shultz; S Werner; E Wojtys; L Engebretsen (June 2008). "Non-contact ACL injuries in female athletes: an International Olympic Committee current concepts statement". Br J Sports Med. 42 (6): 394–412. PMC 3920910

. PMID 18539658. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.048934.

. PMID 18539658. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.048934. - ↑ Boden BP, Sheehan FT, Torg JS, Hewett TE (Sep 2010). "Non-contact ACL Injuries: Mechanisms and Risk Factors". J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 18 (9): 520–27. PMC 3625971

. PMID 20810933.

. PMID 20810933. - ↑ Mohtadi, NG; Chan, DS; Dainty, KN; Whelan, DB (Sep 7, 2011). "Patellar tendon versus hamstring tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament rupture in adults.". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD005960. PMID 21901700. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005960.pub2.

- ↑ Mall, Nathan A.; Chalmers, Peter N.; Moric, Mario; Tanaka, Miho J.; Cole, Brian J.; Bach, Bernard R.; Paletta, George A. (2014-10-01). "Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (10): 2363–2370. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 25086064. doi:10.1177/0363546514542796.

- ↑ Gornitzky, Alex L.; Lott, Ariana; Yellin, Joseph L.; Fabricant, Peter D.; Lawrence, J. Todd; Ganley, Theodore J. (2016-10-01). "Sport-Specific Yearly Risk and Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears in High School Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 44 (10): 2716–2723. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 26657853. doi:10.1177/0363546515617742.

- ↑ Ramski, David E.; Kanj, Wajdi W.; Franklin, Corinna C.; Baldwin, Keith D.; Ganley, Theodore J. (2014-11-01). "Anterior cruciate ligament tears in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of nonoperative versus operative treatment". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (11): 2769–2776. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 24305648. doi:10.1177/0363546513510889.

| Classification |

V · T · D |

|---|---|

| External resources |