8405 Asbolus

| Discovery [1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Spacewatch |

| Discovery site | Kitt Peak Obs. |

| Discovery date | 5 April 1995 |

| Designations | |

| MPC designation | (8405) Asbolus |

| Pronunciation | (/ˈæzbələs/) |

Named after | Asbolus (Greek mythology)[2] |

| 1995 GO | |

| distant [3] · centaur [1][4] | |

| Orbital characteristics [1] | |

| Epoch 4 September 2017 (JD 2458000.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 1 | |

| Observation arc | 16.60 yr (6,063 days) |

| Aphelion | 29.118 AU |

| Perihelion | 6.8145 AU |

| 17.966 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.6207 |

| 76.15 yr (27,815 days) | |

| 71.410° | |

| 0° 0m 46.44s / day | |

| Inclination | 17.638° |

| 6.1324° | |

| 290.06° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions |

66±8 km[1] 76 km[5] 77.5±7.5 km[6] 80.83 km (derived)[4] 84±8 km[7] 85±9 km[8] |

|

4.4682±0.0003 h[9] 8 h[10] 8.870 h[11] 8.932±0.002 h[12] 8.9351 h[13] | |

|

0.04[13] 0.05[7] 0.056±0.019[8] 0.057 (assumed)[4] 0.095±0.015[6] 0.12±0.03[14] 0.13±0.03[1] | |

| BR [15] · C [4] | |

| 8.74[13] · 9.1[1] · 9.11±0.02[16] · 9.13±0.25[8] · 9.18[17] · 9.19[4][18] · 9.257±0.120 (R)[19] · 9.26[9] | |

|

| |

8405 Asbolus (/ˈæzbələs/; from Greek: Άσβολος), provisionally designated 1995 GO, is a centaur orbiting in the outer Solar System between the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune. It was discovered on 5 April 1995, by James Scotti and Robert Jedicke of Spacewatch (credited) at Kitt Peak Observatory in Arizona, United States. It is named after Asbolus, a centaur in Greek mythology and measures approximately 80 kilometers in diameter.[3]

Orbit and classification

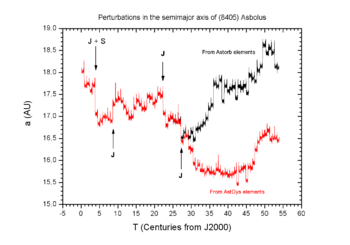

Centaurs have short dynamical lifetimes due to perturbations by the giant planets. Asbolus is estimated to have an orbital half-life of about 860 kiloannum.[21] Asbolus is currently classified as a SN centaur since Saturn is considered to control the perihelion and Neptune controls the aphelion.[21]

It currently has a perihelion of 6.8 AU,[1] so is also influenced by Jupiter. Centaurs with a perihelion less than 6.6 AU are very strongly influenced by Jupiter and for classification purposes are considered to have a perihelion under the control of Jupiter.[21] In about ten thousand years, clones of the orbit of Asbolus suggest that its perihelion classification may come under the control of Jupiter.[22]

Predicting the overall orbit and position of Asbolus beyond a few thousand years is difficult because of errors in the known trajectory, error amplification by perturbations due to all of the gas giants, and the possibility of perturbation as a result of cometary outgassing and fragmentation. Compared to centaur 7066 Nessus, the orbit of Asbolus is currently much more chaotic.

Physical characteristics

No resolved images of it have ever been made, but in 1998 spectral analysis of its composition by the Hubble Space Telescope revealed a fresh impact crater on its surface, less than 10 million years old.[23] Centaurs are dark in colour, because their icy surfaces have darkened after long exposure to solar radiation and the solar wind. However, fresh craters excavate more reflective ice from below the surface, and that is what Hubble has detected on Asbolus.

Naming

This minor planet was named from Greek mythology after Asbolus (Greek for "sooty", "the black one"), a centaur capable to read omens in the flight of birds. He provoked a bloodbath in which the centaurs Chiron and Pholus met their deaths at Heracles' hands. The minor planets 2060 Chiron, 5145 Pholus and 5143 Heracles are named after these mythological figures.[2] The official naming citation was published on 28 September 1999 (M.P.C. 36128).[24]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 8405 Asbolus (1995 GO)" (2011-11-02 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- 1 2 Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – (8405) Asbolus. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 648. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- 1 2 "8405 Asbolus (1995 GO)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "LCDB Data for (8405) Asbolus". Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB). Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Robert Johnston (5 September 2016). "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- 1 2 Stansberry, J. A.; Cruikshank, D. P.; Grundy, W. G.; Margot, J. L.; Emery, J. P.; Fernandez, Y. R.; et al. (August 2005). "Albedos, Diameters (and a Density) of Kuiper Belt and Centaur Objects". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 37: 737. Bibcode:2005DPS....37.5205S. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- 1 2 John Stansberry; Will Grundy; Mike Brown; Dale Cruikshank; John Spencer; David Trilling; Jean-Luc Margot (2007). "Physical Properties of Kuiper Belt and Centaur Objects: Constraints from Spitzer Space Telescope". arXiv:astro-ph/0702538

[astro-ph].

[astro-ph]. - 1 2 3 Duffard, R.; Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Vilenius, E.; Ortiz, J. L.; Mueller, T.; et al. (April 2014). ""TNOs are Cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region. XI. A Herschel-PACS view of 16 Centaurs". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 564: 17. Bibcode:2014A&A...564A..92D. arXiv:1309.0946

. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322377. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322377. Retrieved 25 April 2017. - 1 2 Galád, A. (May 2010). "Accuracy of calibrated data from the SDSS moving object catalog, absolute magnitudes, and probable lightcurves for several asteroids". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 514: 10. Bibcode:2010A&A...514A..55G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014029. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Romanishin, W.; Tegler, S. C.; Levine, J.; Butler, N. (May 1997). "BVR Photometry of Centaur Objects 1995 GO, 1993 HA2, and 5145 Pholus". Astronomical Journal. 113: 1893–1898. Bibcode:1997AJ....113.1893R. doi:10.1086/118402. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Warren R.; Luu, Jane X. (March 1997). "CCD Photometry of the Centaur 1995 GO". Icarus. 126 (1): 218–224. Bibcode:1997Icar..126..218B. doi:10.1006/icar.1996.5643. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Brucker, Melissa; Romanishin, W. J.; Tegler, S. C.; Consolmagno, G. J.; J., S.; Grundy, W. M. (September 2008). "Rotational Properties of Centaurs (32532) Thereus and (8405) Asbolus". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 40: 483. Bibcode:2008DPS....40.4709B. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 Davies, John K.; McBride, Neil; Ellison, Sara L.; Green, Simon F.; Ballantyne, David R. (August 1998). "Visible and Infrared Photometry of Six Centaurs". Icarus. 134 (2): 213–227. Bibcode:1998Icar..134..213D. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.5931. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Fernández, Yanga R.; Jewitt, David C.; Sheppard, Scott S. (February 2002). "Thermal Properties of Centaurs Asbolus and Chiron". The Astronomical Journal. 123 (2): 1050–1055. Bibcode:2002AJ....123.1050F. arXiv:astro-ph/0111395

. doi:10.1086/338436.

. doi:10.1086/338436. - ↑ Belskaya, Irina N.; Barucci, Maria A.; Fulchignoni, Marcello; Dovgopol, Anatolij N. (April 2015). "Updated taxonomy of trans-neptunian objects and centaurs: Influence of albedo". Icarus. 250: 482–491. Bibcode:2015Icar..250..482B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.12.004. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Rabinowitz, David L.; Schaefer, Bradley E.; Tourtellotte, Suzanne W. (January 2007). "The Diverse Solar Phase Curves of Distant Icy Bodies. I. Photometric Observations of 18 Trans-Neptunian Objects, 7 Centaurs, and Nereid". The Astronomical Journal. 133 (1): 26–43. Bibcode:2007AJ....133...26R. doi:10.1086/508931. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Romanishin, W.; Tegler, S. C. (December 2005). "Accurate absolute magnitudes for Kuiper belt objects and Centaurs". Icarus. 179 (2): 523–526. Bibcode:2005Icar..179..523R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.06.016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Romanishin, W.; Tegler, S. C. (March 1999). "Rotation rates of Kuiper-belt objects from their light curves". Nature. 398 (6723): 129–132.(NatureHomepage). Bibcode:1999Natur.398..129R. doi:10.1038/18168. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Peixinho, N.; Delsanti, A.; Guilbert-Lepoutre, A.; Gafeira, R.; Lacerda, P. (October 2012). "The bimodal colors of Centaurs and small Kuiper belt objects". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 546: 12. Bibcode:2012A&A...546A..86P. arXiv:1206.3153

. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219057. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219057. Retrieved 22 September 2016. - ↑ "Three clones of Centaur 8405 Asbolus making passes within 450Gm". Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2009. (Solex 10) Archived 29 April 2009 at WebCite

- 1 2 3 Horner, J.; Evans, N.W.; Bailey, M. E. (November 2004). "Simulations of the Population of Centaurs I: The Bulk Statistics". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 354 (3): 798–810. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.354..798H. arXiv:astro-ph/0407400

. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08240.x.

. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08240.x. - ↑ "The perihelion (q) of twenty-two clones of Centaur Asbolus". Retrieved April 26, 2009. (Solex 10) Archived 29 April 2009 at WebCite

- ↑ "Centaur's Bright Surface Spot Could be Crater of Fresh Ice". Hubblesite (STScI-2000-31). September 14, 2000. Retrieved April 12, 2004.

- ↑ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

External links

- Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB), query form (info)

- Dictionary of Minor Planet Names, Google books

- Asteroids and comets rotation curves, CdR – Observatoire de Genève, Raoul Behrend

- Discovery Circumstances: Numbered Minor Planets (5001)-(10000) – Minor Planet Center

- 8405 Asbolus at the JPL Small-Body Database