Fifth Avenue

Route map: Google

|

The Museum Mile section of Fifth Avenue at the Metropolitan Museum of Art at 81st Street | |

| Other name(s) | Museum Mile |

|---|---|

| Owner | City of New York |

| Maintained by | NYCDOT |

| Length | 6.2 mi[1][2] (10.0 km) |

| Location | Manhattan, New York City |

| South end | Washington Square North in Greenwich Village |

| Major junctions |

Madison Square in Flatiron Grand Army Plaza in Midtown Duke Ellington Circle in East Harlem Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem Madison Avenue Bridge in Harlem |

| North end |

|

| East |

University Place (south of 14th) Broadway (14th to 23rd) Madison Avenue (north of 23rd) |

| West |

Sixth Avenue (south of 59th) Central Park-East Drive (59th to 110th) Lenox Avenue (north of 110th) |

| Construction | |

| Commissioned | March 1811 |

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, United States. It stretches from West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square North at Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. It is considered among the most expensive and best shopping streets in the world.[3][4]

History

The lower stretch of Fifth Avenue extended the stylish neighborhood of Washington Square northwards. The high status of Fifth Avenue was confirmed in 1862, when Caroline Schermerhorn Astor settled on the southwest corner of 34th Street, and the beginning of the end of its reign as a residential street was symbolized by the erection, in 1893, of the Astoria Hotel on the site of her house, later linked to its neighbor as the Waldorf–Astoria Hotel (now the site of the Empire State Building). Fifth Avenue is the central scene in Edith Wharton's 1920 Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Age of Innocence. The novel describes New York's social elite in the 1870s and provides historical context to Fifth Avenue and New York's aristocratic families.

Originally a narrower thoroughfare, much of Fifth Avenue south of Central Park was widened in 1908, sacrificing its wide sidewalks to accommodate the increasing traffic. The midtown blocks, now famously commercial, were largely a residential district until the start of the 20th century. The first commercial building on Fifth Avenue was erected by Benjamin Altman who bought the corner lot on the northeast corner of 34th Street in 1896, and demolished the "Marble Palace" of his arch-rival, A. T. Stewart. In 1906 his department store, B. Altman and Company, occupied the whole of its block front. The result was the creation of a high-end shopping district that attracted fashionable women and the upscale stores that wished to serve them. Lord & Taylor's flagship store is still located on Fifth Avenue near the Empire State Building and the New York Public Library.

In the 1920s, traffic towers controlled important intersections from 14th to 59th Streets.

Description

Fifth Avenue originates at Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village and runs northwards through the heart of Midtown, along the eastern side of Central Park, where it forms the boundary of the Upper East Side and through Harlem, where it terminates at the Harlem River at 142nd Street. Traffic crosses the river on the Madison Avenue Bridge. Fifth Avenue serves as the dividing line for house numbering and west-east streets in Manhattan, just as Jerome Avenue does in the Bronx. It separates, for example, East 59th Street from West 59th Street. From this zero point for street addresses, numbers increase in both directions as one moves away from Fifth Avenue, with 1 West 58th Street on the corner at Fifth Avenue, and 300 West 58th Street located three blocks to the west of it.

The section of Fifth Avenue that crosses Midtown Manhattan, especially that between 49th Street and 60th Street, is lined with prestigious shops and is consistently ranked among the most expensive shopping streets in the world.[3] The "most expensive street in the world" moniker changes depending on currency fluctuations and local economic conditions from year to year. For several years starting in the mid-1990s, the shopping district between 49th and 57th Streets was ranked as having the world's most expensive retail spaces on a cost per square foot basis.[4] In 2008, Forbes magazine ranked Fifth Avenue as being the most expensive street in the world. Some of the most coveted real estate on Fifth Avenue are the penthouses perched atop the buildings.[5]

The American Planning Association (APA) compiled a list of "2012 Great Places in America" and declared Fifth Avenue to be one of the greatest streets to visit in America. This historic street has many world-renowned museums, businesses and stores, parks, luxury apartments, and historical landmarks that are reminiscent of its history and vision for the future.[6]

Historical landmarks

New York City landmarks

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission is the New York City agency that is responsible for identifying and designating the City's landmarks and the buildings in the City's historic districts. Below is a list of historic sites on Fifth Avenue with their designation dates:[7]

- 500 Fifth Avenue Building – December 14, 2010

- Aeolian Building (Elizabeth Arden Building) – (689 Fifth Avenue at 54th Street) – December 10, 2002

- George W. Vanderbilt Residence – (647 Fifth Avenue) – March 22, 1977

- Goelet Building (Swiss Center Building) – (606–608 Fifth Avenue at 49th Street) – January 14, 1992

- Gorham Building – (390 Fifth Avenue at 36th Street) – December 15, 1998

- Lord & Taylor (424-428 Fifth Avenue) – December 2007

- Manufacturers Trust Company Building – (510 Fifth Avenue at 43rd Street) – April 23, 1985

- Rizzoli Building – (712 Fifth Avenue) – January 29, 1985

- Saks Fifth Avenue – (611 Fifth Avenue) – December 20, 1984

- Sidewalk Clock – (200 Fifth Avenue) and (522 Fifth Avenue) – August 25, 1981

- St. Regis Hotel – (799 Fifth Avenue at 55th Street) – November 1, 1988

National Historic Landmarks

The National Historic Landmark program (NRHP) focuses on places of significance in American history, architecture, engineering, or culture. It recognizes structures, buildings, sites, and districts associated with important events, people, or architectural movements. Listed below is a list of National Historic Landmarks located along Fifth Avenue:[8]

- Empire State Building – 350 Fifth Avenue – National Historic Landmark (06/24/86)

- Flatiron Building – 175 Fifth Avenue – National Historic Landmark (06/29/89)

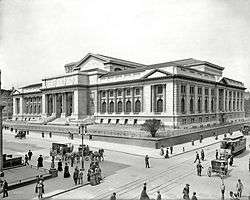

- New York Public Library – Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street – National Historic Landmark (12/21/65)

- Rockefeller Center − 45 Rockefeller Plaza – National Historic Landmark (12/23/87)

- St. Patrick's Cathedral – 460 Madison Avenue – National Historic Landmark (12/08/76)

Other

In addition, the cooperative apartment building at 2 Fifth Avenue was named a New York cultural landmark on December 12, 2013 by the Historic Landmark Preservation Center, as the last residence of former New York City Mayor Ed Koch.[9]

Traffic pattern

Fifth Avenue from 142nd Street to 135th Street carries two-way traffic. Fifth Avenue carries one-way traffic southbound from 135th Street to Washington Square North. The changeover to one-way traffic south of 135th Street took place on January 14, 1966, at which time Madison Avenue was changed to one way uptown (northbound).[10] From 124th Street to 120th Street, Fifth Avenue is cut off by Marcus Garvey Park, with southbound traffic diverted around the park via Mount Morris Park West.

Fifth Avenue is one of the few major streets in Manhattan along which streetcars did not operate. Instead, Fifth Avenue Coach offered a service more to the taste of fashionable gentlefolk, at twice the fare. On May 23, 2008, The New York Times reported that the New York City area Metropolitan Transportation Authority's bus division is considering the use of double-decker buses on Fifth Avenue once again, where they were operated by the Fifth Avenue Coach Company until 1953,[11] and again by MTA from 1976 to 1978.

%2C_at_the_244th_Annual_NYC_St._Patrick's_Day_parade.jpg)

Parade route

Fifth Avenue is the traditional route for many celebratory parades in New York City; thus, it is closed to traffic on numerous Sundays in warm weather. The longest running parade is the annual St. Patrick's Day Parade. Parades held are distinct from the ticker-tape parades held on the "Canyon of Heroes" on lower Broadway, and the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade held on Broadway from the Upper West Side downtown to Herald Square. Fifth Avenue parades usually proceed from south to north, with the exception of the LGBT Pride March, which goes north to south to end in Greenwich Village. The Latino literary classic by New Yorker Giannina Braschi, entitled "Empire of Dreams," takes place on the Puerto Rican Day Parade on Fifth Avenue.[12][13]

Bicycling route

Bicycling on Fifth Avenue ranges from segregated with a bike lane south of 23rd Street, to scenic along Central Park, to dangerous through Midtown with very heavy traffic during rush hours.[14] There is no dedicated bike lane along Fifth Avenue.

In July 1987, then New York City Mayor Edward Koch proposed banning bicycling on Fifth, Park, and Madison Avenues during weekdays, but many bicyclists protested and had the ban overturned.[15] When the trial was started on Monday, August 24, 1987 for 90 days to ban bicyclists from these three avenues from 31st Street to 59th Street between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. on weekdays, mopeds would not be banned.[16] On Monday, August 31, 1987, a state appeals court judge halted the ban for at least a week pending a ruling after opponents against the ban brought a lawsuit.[17]

Nicknames

Upper Fifth Avenue/Millionaire's Row

In the late 19th century, the very rich of New York began building mansions along the stretch of Fifth Avenue between 59th Street and 96th Street, looking onto Central Park. By the early 20th century, this portion of Fifth Avenue had been nicknamed "Millionaire's Row", with mansions such as the Mrs. William B. Astor House, William A. Clark House, Felix M. Warburg House, two Morton F. Plant Houses, James B. Duke House and numerous others (see Category:Fifth Avenue, below). Entries to Central Park along this stretch include Inventor's Gate at 72nd Street, which gave access to the park's carriage drives, and Engineers' Gate at 90th Street, used by equestrians.

A milestone change for Fifth Avenue came in 1916, when the grand corner mansion at 72nd Street and Fifth Avenue that James A. Burden II had erected in 1893 became the first private mansion on Fifth Avenue above 59th Street to be demolished to make way for a grand apartment house. The building at 907 Fifth Avenue began a trend, with its 12 stories around a central court, with two apartments to a floor.[18] Its strong cornice above the fourth floor, just at the eaves height of its neighbors, was intended to soften its presence.

In January 1922, the city reacted to complaints about the ongoing replacement of Fifth Avenue's mansions by apartment buildings by restricting the height of future structures to 75 feet (23 m), about half the height of a ten-story apartment building.[19] Architect J. E. R. Carpenter brought suit, and won a verdict overturning the height restriction in 1923. Carpenter argued that "the avenue would be greatly improved in appearance when deluxe apartments would replace the old-style mansions."[19] Led by real estate investors Benjamin Winter, Sr. and Frederick Brown, the old mansions were quickly torn down and replaced with apartment buildings.[20]

This area contains many notable apartment buildings, including 810 Fifth Avenue and the Park Cinq, many of them built in the 1920s by architects such as Rosario Candela and J. E. R. Carpenter. A very few post-World War II structures break the unified limestone frontage, notably the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum between 88th and 89th Streets.

Museum Mile

Museum Mile is the name for a section of Fifth Avenue running from 82nd to 105th streets on the Upper East Side,[21][22] in an area sometimes called Upper Carnegie Hill.[23] The Mile, which contains one of the densest displays of culture in the world, is actually three blocks longer than one mile (1.6 km). Nine museums occupy the length of this section of Fifth Avenue.[24] A ninth museum, the Museum for African Art, joined the ensemble in 2009; its Museum at 110th Street, the first new museum constructed on the Mile since the Guggenheim in 1959,[25] opened in late 2012.

In addition to other programming, the museums collaborate for the annual Museum Mile Festival to promote the museums and increase visitation.[26] The Museum Mile Festival traditionally takes place here on the second Tuesday in June from 6 – 9 p.m. It was established in 1979 to increase public awareness of its member institutions and promote public support of the arts in New York City.[27] The first festival was held on June 26, 1979.[28] The nine museums are open free that evening to the public. Several of the participating museums offer outdoor art activities for children, live music and street performers.[29] During the event, Fifth Avenue is closed to traffic.

Museums on the mile include:

- 110th Street – Museum for African Art[30]

- 105th Street – El Museo del Barrio

- 103rd Street – Museum of the City of New York

- 92nd Street – The Jewish Museum

- 91st Street – Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum (part of the Smithsonian Institution)

- 89th Street – National Academy Museum and School of Fine Arts

- 88th Street – Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- 86th Street – Neue Galerie New York

- 82nd Street – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Additionally, on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 70th Street lies the Henry Clay Frick House which houses the Frick Collection, though this is not part of Museum Mile.

Economy

Between 49th Street and 60th Street, is lined with prestigious boutiques and flagship stores and is consistently ranked among the most expensive shopping streets in the world.[31]

Many luxury goods, fashion, and sport brand boutiques are located on Fifth Avenue, including Louis Vuitton, Tiffany & Co., Gucci, Prada, Armani, Tommy Hilfiger, Cartier, Omega, Chanel, Harry Winston, Salvatore Ferragamo, Nike, Escada, Swarovski, Bvlgari, Emilio Pucci, Ermenegildo Zegna, Abercrombie & Fitch, De Beers, Emanuel Ungaro, Gap, Lindt Chocolate Shop, Henri Bendel, NBA Store, Oxxford Clothes, Microsoft Store, Sephora, Zara, and H&M. Luxury department stores include Lord & Taylor, Saks Fifth Avenue and Bergdorf Goodman. Fifth Avenue also is home to New York's fifth most photographed building, the Apple Store.

Many airlines at one time had ticketing offices along Fifth Avenue. In the years leading up to 1992, the number of ticketing offices along Fifth Avenue decreased. Pan American World Airways went out of business, while Air France, Finnair, and KLM moved their ticket offices to other areas in Midtown Manhattan.[32]

Gallery

_pg319_BIRD'S-EYE_VIEW_OF_FIFTH_AVENUE%3B_NORTH_OF_51ST_STREET.jpg) Bird's-eye view looking north from 51st St. c. 1893

Bird's-eye view looking north from 51st St. c. 1893 Street view looking north from 51st St. c. 1895

Street view looking north from 51st St. c. 1895 The same shot in March 2015

The same shot in March 2015

Christmas on Fifth Avenue in 1896

Christmas on Fifth Avenue in 1896 Fifth Avenue, 1918

Fifth Avenue, 1918

- Fifth Avenue begins at the Washington Square Arch in Washington Square Park

- Memorial to New York architect Richard Morris Hunt, Fifth Avenue between 70th and 71st Streets

The Plaza Hotel, c.1907

The Plaza Hotel, c.1907

See also

- List of shopping streets and districts by city

- Jerome Avenue, a shopping street and major thoroughfare in the Bronx

- Fifth Avenue Mile, annual road race

References

Notes

- ↑ Google (September 12, 2015). "Fifth Avenue (south of 120th Street)" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ↑ Google (September 12, 2015). "Fifth Avenue (north of 124th Street)" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- 1 2 "Fifth Avenue The World's Most Expensive Shopping Street (PHOTOS) (Subtext: "For the 9th year in a row, Fifth Avenue between 39th and 60th Streets ranks first among Cushman & Wakefield's Main Streets Across the World Report, according to the New York Post.")". HuffingtonPost.com, Inc. September 21, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- 1 2 Foderaro, Lisa W. "Survey Reaffirms 5th Ave. at Top of the Retail Rent Heap", The New York Times, April 29, 1997. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ↑ New York Penthouses for Sale

- ↑ Great Places in America. Planning.org (February 24, 2011). Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ↑ Landmarks Preservation Commission – Home. Nyc.gov. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ↑ (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20110124220051/http://www.nps.gov/nhl/designations/Lists/NY01.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 24, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Roberts, Sam (12 December 2013). "Koch’s Last Residence Is Named a Cultural Landmark". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ Kihbaconss, Peter. "5th and Madison Avenues Become One-Way Friday; Change to Come 7 Weeks Ahead of Schedule to Ease Strike Traffic 5th and Madison to Be Made One-Way Friday", The New York Times, January 12, 1966. Retrieved December 6, 2007. "The long-argued conversion of Fifth and Madison Avenues to one-way streets will start at 6 am. Friday seven weeks ahead of schedule to ease congestion caused by the transit strike."

- ↑ Neuman, William "Step to the Rear of the Bus, Please, or Take a Seat Upstairs", The New York Times, Tuesday, May 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Giannina Braschi". National Book Festival. Library of Congress. 2012.

’Braschi, one of the most revolutionary voices in Latin America today’ is the author of Empire of Dreams.

- ↑ Marting, Diane (2010), New/Nueva York in Giannina Braschi's 'Poetic Egg': Fragile Identity, Postmodernism, and Globalization, Indiana: The Global South, pp. 167–182.

- ↑ New York City Cycling Map, New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ Dunham, Mary Frances. "Bicycle Blueprint – Fifth, Park and Madison", Transportation Alternatives. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ Yee, Marilynn K. "Ban on Bikes Could Bring More Mopeds", The New York Times, Tuesday, August 25, 1987. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ Higgins Jr., Chester. "Bike Messengers: Life in Tight Lane", The New York Times, Friday, September 4, 1987. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ The smallest apartment was a half-floor, of 12 rooms; 907 Fifth Avenue.

- 1 2 J. E. R. Carpenter, The Architect Who Shaped Upper Fifth Avenue, New York Times, August 26, 2007, Christopher Gray,

- ↑ Entrepreneur Magazine: "Built for Business: Midtown Manhattan in the 1920s". Retrieved November 11, 2014

- ↑ Ng, Diana. "Museum Mile" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010), The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.), New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2, p.867

- ↑ Street signs saying "Museum Mile" actually extend to 80th Street. "Street View: 80th Street and Fifth Avenue, New York" Google Maps

- ↑ Kusisto, Laura (October 21, 2011). "Reaching High on Upper 5th Avenue". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Museums on the Mile". Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ↑ Sewell Chan (February 9, 2007). "Museum for African Art Finds its Place". The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ↑ "New Drive Promoting 5th Ave.'s 'Museum Mile'". The New York Times. June 27, 1979. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Museum Mile Festival held in New York" UPI NewsTrack (June 8, 2004.)

- ↑ New drive promoting Fifth Avenue's 'Museum Mile', The New York Times, June 27, 1979.

- ↑ Fass, Allison and Murray, Liz (2000) "Talking to the Streets for Art" The New York Times June 11, 2000, p.17, col. 2.

- ↑ Catton, Pia (June 14, 2011). "Another Delay for Museum of African Art". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Fifth Avenue The World's Most Expensive Shopping Street (PHOTOS) (Subtext: "For the 9th year in a row, Fifth Avenue between 49th and 60th Streets ranks first among Cushman & Wakefield's Main Streets Across the World Report, according to the New York Post.")". HuffingtonPost.com, Inc. September 21, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ "POSTINGS: Air France Takes Flight; Au Revoir, Fifth Avenue." The New York Times. May 24, 1992. Page 101, New York Edition. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

Further reading

- Gaines, Steven (2005). The Sky's the Limit: Passion and Property in Manhattan. New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-60851-3.

- "Museum Mile". NY.com. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Daly, Sean (April 13, 2003). "Museum Mile High". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 15, 2008. (Note: Erroneously states the northern boundary of Museum Mile is East 104th Street.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 5th Avenue (Manhattan). |

- Fifth Avenue Photos

- Fifth Avenue Directory and Images

- Greek Independence Day Parade, Fifth Avenue

- New York Songlines: Fifth Avenue

- APA Great Places in America

- National Historic Landmarks in New York State