5 October 1910 revolution

| 5 October 1910 Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contemporary commemorative illustration of the Proclamation of the Portuguese Republic on 5 October 1910. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| About 7,000 men |

About 2,000 revolutionaries 3 cruisers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| At least 37 dead and dozens wounded, with at least 14 of them dying in the following days. | |||||||

The establishment of the Portuguese Republic was the result of a coup d'état organised by the Portuguese Republican Party which, on 5 October 1910, deposed the constitutional monarchy and established a republican regime in Portugal. The subjugation of the country to British colonial interests,[1] the royal family's expenses,[2] the power of the Church, the political and social instability, the system of alternating power of the two political parties (Progressive and Regenerador), João Franco's dictatorship,[3] an apparent inability to adapt to modern times – all contributed to an unrelenting erosion of the Portuguese monarchy.[4] The proponents of the republic, particularly the Republican Party, found ways to take advantage of the situation.[5] The Republican Party presented itself as the only one that had a programme that was capable of returning to the country its lost status and place Portugal on the way of progress.[6]

After a reluctance of the military to combat the nearly two thousand soldiers and sailors that rebelled between 3 and 4 October 1910, the Republic was proclaimed at 9 o'clock of the next day from the balcony of the Paços do Concelho in Lisbon.[7] After the revolution, a provisional government led by Teófilo Braga directed the fate of the country until the approval of the Constitution in 1911 that marked the beginning of the First Republic.[8] Among other things, with the establishment of the republic, national symbols were changed: the national anthem and the flag. The revolution produced some civil and religious liberties, although there was no advance in women's rights and in workers rights, unlike what happened in other European countries.

Background

1890 British Ultimatum and 31 January rebellion

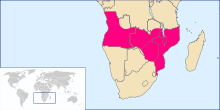

On 11 January 1890 the British government of Lord Salisbury sent the Portuguese government an ultimatum[9] in the form of a "memorandum", demanding the retreat of the Portuguese military forces led by Serpa Pinto from the territory between the colonies of Angola and Mozambique (in the current Zimbabwe and Zambia), an area claimed by Portugal under the Pink Map.[10]

The swift yielding by the Portuguese to the British demands was seen as a national humiliation by a broad cross-section of the population and the elite,[11] initiating a movement of deep dissatisfaction in relation with the new king, Carlos I of Portugal, the royal family and the institution of the monarchy, which were seen as responsible for the alleged process of "national decline". The situation was aggravated by the severe financial crisis that occurred between 1890 and 1891, when the money sent from emigrants in Brazil decreased by 80% with the so-called crisis of encilhamento following the proclamation of the republic in Brazil two months previously, an event that was followed with apprehension by the monarchic government and with jubilation by the defenders of the republic in Portugal. The republicans knew how to take advantage of the dissatisfaction, initiating an increase of their social support base that would climax in the demise of the regime.[12]

On 14 January, the progressive government fell and the leader of the Regenerador Party, António de Serpa Pimentel, was chosen to form the new government.[13] The progressivists then began to attack the king, voting for republican candidates in the March election of that year, questioning the colonial agreement then signed with the British. Feeding an atmosphere of near insurrection, on 23 March 1890, António José de Almeida, at the time a student in the University of Coimbra and, later on, President of the Republic, published an article entitled "Bragança, o último",[14] considered slanderous against the king and led to Almeida's imprisonment.

On 1 April 1890, the explorer Silva Porto self-immolated wrapped in a Portuguese flag in Kuito, Angola, after failed negotiations with the locals, under orders of Paiva Couceiro, which he attributed to the ultimatum. The death of the well-known explorer of the African continent generated a wave of national sentiment,[15] and his funeral was followed by a crowd in Porto.[16][17] On 11 April, Guerra Junqueiro's poetic work Finis Patriae, a satire criticising the King, went on sale.[18]

In the city of Porto, on 31 January 1891, a military uprising against the monarchy took place, constituted mainly by sergeants and enlisted ranks.[19] The rebels, who used the nationalist anthem A Portuguesa as their marching song, took the Paços do Concelho, from whose balcony, the republican journalist and politician Augusto Manuel Alves da Veiga proclaimed the establishment of the republic in Portugal and hoisted a red and green flag belonging to the Federal Democratic Centre. The movement was, shortly afterwards, suppressed by a military detachment of the municipal guard that remained loyal to the government, resulting in 40 injured and 12 casualties. The captured rebels were judged. 250 received sentences of between 18 months and 15 years of exile in Africa.[20] A Portuguesa was forbidden.

Despite its failure, the rebellion of 31 January 1891 was the first large threat felt by the monarchic regime and a sign of what would come almost two decades later.[21]

The Portuguese Republican Party

| “ | Thinking and science are republican, because creative genius lives on freedom and only a Republic can be truly free […]. Labour and industry are republican, because the creative activity wants security and stability and only a Republic […] is stable and secure […]. A Republic is, in the state, liberty […]; in industry, production; in labour, security; in the nation, strength and independence. For all, wealth; for all, equality; for all, light." | ” |

| — Antero de Quental, in República, 11-05-1870[22] | ||

The revolutionary movement of 5 October 1910 occurred following the ideological and political action that, since its creation in 1876, the Portuguese Republican Party (PRP) had been developing with the objective of overthrowing the monarchic regime.[23]

By making the national renewal dependent on the end of the monarchy, the Republican Party managed to define itself as distinct from the Portuguese Socialist Party, which defended a collaboration with the regime in exchange for the rights of the working class and attracted the sympathy of the dissatisfied sections of society.

Disagreements within the party became more connected with matters of political than ideological strategy. The ideological direction of the Portuguese republicanism had been traced much earlier by the works of José Félix Henriques Nogueira, little changed through the years, except in terms of later adaptation to the everyday realities of the country. The works of Teófilo Braga contributed to this task by trying to concretise the decentralising and federalist ideas, abandoning the socialist quality in favour of democratic aspects. This change also aimed to attract the small and medium bourgeoisie, which turned into one of the main bases of republican support. In the election of 13 October 1878 the PRP elected its first member of parliament, José Joaquim Rodrigues de Freitas, for Porto.[24]

There was also an intention to give the overthrow of the monarchy overtones of unification, nationalism and being above the particular interests of individual social classes.[25] This panacea that would cure, once and for all, all the ills of the nation, elevating it to glory, emphasised two fundamental tendencies: nationalism and colonialism. From this combination came the final desertion of Iberian Federalism, patent in the first republican theses by José Félix Henriques Nogueira,[26] identifying the monarchy as antipatriotism and the yielding to foreign interests. Another strong component of republican ideology was emphasised by anti-clericalism,[27] due to the theorisation of Teófilo Braga, who identified religion as an obstacle to progress and responsible for the scientific retardation of Portugal, in opposition to republicanism, which was linked by him to science, progress and well-being.[28]

Ideological issues were not, ultimately, fundamental to the republican strategy: for the majority of sympathisers, who didn't even know the texts of the main manifestos, it was enough to be against the monarchy, against the Church and against the political corruption of traditional parties. This lack of ideological preoccupation doesn't mean that the party didn't bother to spread its principles. The most effective action of dissemination was the propaganda made through its rallies and popular demonstrations and bulletins such as A Voz Pública (The Public Voice) in Porto, O Mundo (The World, from 1900) and A Luta (The Struggle, from 1906) in Lisbon.

The republican propaganda managed to take advantage of some historical facts with popular repercussions. The celebrations of the third centenary of the death of Luís de Camões in 1580, and the British ultimatum in 1890, for example, were capitalised on to present the republicans as the true representatives of the purest national sentiments and popular aspirations.

The third centenary of Camões was commemorated with great celebrations: a civic entourage that went through the streets of Lisbon, in the middle of great popular enthusiasm and, also, the transfer of the remains of Camões and Vasco da Gama to Jerónimos Monastery.[29] The atmosphere of the national celebration that characterised the commemorations complemented the patriotic exaltation. The idea of the Camões commemorations came from the Lisbon Geographic Society, but the execution was entrusted to a commission constituted by, amongst others, Teófilo Braga, Ramalho Ortigão, Jaime Batalha Reis, Magalhães Lima and Pinheiro Chagas, leading figures of the Republican Party.[30]

Besides Rodrigues de Freitas, Manuel de Arriaga, José Elias Garcia, Zófimo Consiglieri Pedroso, José Maria Latino Coelho, Bernardino Pereira Pinheiro, Eduardo de Abreu, Francisco Teixeira de Queirós, José Jacinto Nunes, and Francisco Gomes da Silva were also elected members of parliament, representing the PRP in various legislative sessions between 1884 and 1894. From this date to 1900 there was no republican parliamentary representation. In this phase, while separated from parliament, the party committed itself to its internal organisation.

After a period of great repression of PRP, the republican movement could reenter the legislative race in 1900, electing four parliament members: Afonso Costa, Alexandre Braga, António José de Almeida and João de Meneses.

1908 Lisbon regicide

On 1 February 1908, while returning to Lisbon from Vila Viçosa in Alentejo, where they had spent the hunting season, the king Carlos I and his heir the prince Luís Filipe were assassinated in Lisbon's Commerce Square.[31]

The attack occurred after a progressive decline of the Portuguese political system, effective since the Regeneration,[32] due in part by the political erosion originated from the system of rotating governments (which saw the Progressive Party and Regenerator Party alternating in government). The king, as arbiter of the system, a role attributed to him by the Constitution, had designated João Franco as the president of the Council of Ministers (government chief).[33] João Franco, dissident of the Regenerator Party, convinced the king to dissolve the parliament so that he could implement a series of measures with the aim to moralise Portuguese politics.[34] This decision irritated not only the republican but also the monarchical opposition, led by political rivals of Franco who accused him of governing in dictatorship. The events were aggravated by the issues of the advanced payments to the Royal House and the signing of the decree of 30 January 1908 that foresaw the banishment to the colonies, without judgement, of those involved in a failed republican coup occurred two days previously, the Municipal Library Elevator Coup.[35]

| “ | I saw a man with a black beard […] open a cape and take out a carbine […]. When I saw [him] […] aiming at the carriage I realised, unfortunately, what it was. My God, the horror of what then happened! Soon after Buíça opened fire […] started a perfect shooting, like a fight among beasts. The Palace Square was deserted, not a soul! This is what I find hardest to forgive João Franco… | ” |

| — D. Manuel II[36] | ||

The Royal Family was in the Ducal Palace of Vila Viçosa, but the events led the king to bring forward his return to Lisbon, taking a train from the station of Vila Viçosa on the morning of 1 February. The royal escort arrived in Barreiro in the evening where, to cross the Tagus, it took a steam boat to Terreiro do Paço in Lisbon, at around 5pm.[37] Despite the atmosphere of great tension, the king chose to continue in an open carriage, with a reduced escort, to demonstrate normality. While greeting the crowds present in the square, the carriage was struck by several shots. One of the carbine bullets hit the king's neck, killing him immediately. More shooting followed, and the prince was hit by another shot. The queen defended herself with the bouquet of flowers offered by the people, which she used to hit one of the attackers who had climbed onto the carriage. The prince D. Manuel was also struck on an arm. Two of the attackers, Manuel Buíça, primary school teacher, and Alfredo Luís da Costa, commerce employee and editor, were killed in the scene. Others managed to escape. The carriage entered the Navy Arsenal, where the deaths of the king and his heir were verified.

After the attack, João Franco's government was dismissed and a rigorous investigation was launched which found, two years later, that the attack had been committed by members of the secret organisation Carbonária.[38] The investigation process finished on 5 October 1910. However, more suspects were subsequently found to have direct involvement, some of whom had gone into hiding in Brazil and France and at least two had been killed by the Carbonária itself.[39]

Europe was shocked by the attack, since King Carlos was highly regarded by other European heads of state.[40] The Lisbon regicide hastened the end of the monarchy by placing D. Manuel II on the throne and throwing the monarchical parties against one another.

The agony of the monarchy

| “ | Their [the republicans'] shows of strength on the streets of Lisbon – for example, on 2 August 1909, which brought together fifty thousand people, with an impressive discipline – echo the riots organised in the Assembly by some republican Parliament representatives. It was on the night of 2 August that I understood that the crown was at stake: when the king, rightly or wrongly, is contested or rejected by a part of the opinion, he can no longer fulfil his unifying role. | ” |

| — Amélie of Orléans[41] | ||

Due to his young age (18 years) and the tragic and bloody way in which he reached power, Manuel II of Portugal obtained an initial sympathy from the public.[42] The young king began his rule by nominating a consensus government presided by admiral Francisco Joaquim Ferreira do Amaral. This government of pacification, as it became known, despite achieving a temporary calm, only lasted for a short amount of time.[43] The political situation degraded again quickly, leading to having seven different governments in the space of two years. The monarchical parties rose against each other once more and fragmented into splinter groups, while the Republican Party continued to gain ground. In the election of 5 April 1908, the last legislative elections to occur during the monarchy, seven members were elected to parliament, among which were Estêvão de Vasconcelos, Feio Terenas and Manuel de Brito Camacho. In the election of 28 August 1910 the party had a resounding success, electing 14 members to parliament, 10 for Lisbon.[44]

Meanwhile, in spite of the evident electoral success of the republican movement, the most revolutionary sector of the party called for armed struggle as the best means to achieve power in a short amount of time. It was this faction that came victorious from the party congress that took place in Setúbal between the 23 and 25 April 1909.[45] The directorate, composed by the moderate Teófilo Braga, Basílio Teles, Eusébio Leão, José Cupertino Ribeiro and José Relvas, received from the congress the imperative mandate to start the revolution. The logistic role for the preparation of plot was assigned to the most radical elements. The civil committee was formed by Afonso Costa, João Pinheiro Chagas and António José de Almeida, while the admiral Carlos Cândido dos Reis was the leader of the military committee.[46] António José de Almeida was assigned the role of organising the secret societies such as the Carbonária – in whose leadership was integrated the naval commissary António Machado Santos[47] —, the freemasons and the Junta Liberal, led by Miguel Bombarda. This eminent doctor played an important part in the dissemination of republican propaganda among the bourgeoisie, which brought many sympathisers to the republican cause.[48]

The period between the congress of 1909 and the emergence of the revolution was marked by great instability and political and social unrest,[49] with several threats of uprising risking the revolution due to the impatience of the navy, led by Machado Santos, who was ready for action.

The uprising

On 3 October 1910 the republican uprising foreshadowed by the political unrest finally took place.[50] Although many of those involved in the republican cause avoided participation in the uprising, making it seem like the revolt had failed, it eventually succeeded thanks to the government's inability to gather enough troops to control the nearly two hundred armed revolutionaries that resisted in the Rotunda.[51]

Movements of the first revolutionaries

In summer of 1910 Lisbon was teeming with rumours and many times the President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) Teixeira de Sousa was warned of imminent coups d'état.[52] The revolution was not an exception: the coup was expected by the government,[53] who on 3 October gave orders for all the garrison troops of the city to be on guard. After a dinner offered in honour of D. Manuel II by Brazilian president Hermes da Fonseca, then on a state visit to Portugal,[54] the monarch retreated to the Palace of Necessidades while his uncle and sworn heir to the throne, prince D. Afonso, went on to the Citadel of Cascais.[55]

After the murder of Miguel Bombarda, shot by one of his patients,[56] the republican leaders assembled with urgency on the night of the 3rd.[57] Some officials were against the meeting due to the strong military presence, but admiral Cândido dos Reis insisted for it to take place, saying "A Revolução não será adiada: sigam-me, se quiserem. Havendo um só que cumpra o seu dever, esse único serei eu." ("The Revolution will not be delayed: follow me, if you want. If there is one that fulfills its duty, this one will be me.").[58][59]

Machado Santos had already got into action and didn't attend the assembly. Instead, he went to the military quarters of the 16th Infantry Regiment[60] where a revolutionary corporal had triggered a rebellion involving the majority of the garrison. A commander and a captain were killed when they made an attempt to control it. Entering a barracks with dozens of members of the Carbonaria, the naval officer went on with about 100 soldiers that entered the 1st Artillery Regiment,[61] where the captain Afonso Palla and a few sergeants, introducing some civilians into the barracks, had already taken administration and captured all officials that refused to join them.[62] With the arrival of Machado Santos two columns were formed which were placed under the leadership of captains Sá Cardoso and Palla. The first went to meet the 2nd regiments of infantry and light infantry, also sympathisers of the rebellion, to go on to Alcântara where it was to support the naval barracks. The original route intersected with a Municipal Guard outpost which forced the column to follow a different route. After a few confrontations with the police and civil forces, it finally found the column led by Palla. Together, the columns advanced to Rotunda, where they entrenched at around 5am. The stationed force was composed of around 200 to 300 men of the 1st, 50th and 60th Regiments of Artillery, 50 to 60 men of Infantry 16 and around 200 civilians. The captains Sá Cardoso and Palla and the naval commissary Machado Santos were among the 9 officials in command.

Meanwhile, lieutenant Ladislau Parreira and some officials and civilians entered the barracks of the Naval Corps of Alcântara at 1am, managing to take arms, provoke a revolt and capture the commanders, one of whom was wounded.[63] The aim of this action was to prevent the exit of the cavalry unit of the Municipal Guard, an aim that was achieved.[64] For this end, they required the support of 3 warships anchored in the Tagus. By this time, lieutenant Mendes Cabeçadas had already taken command of the mutinied crew of the NRP Adamastor[65] while the mutinied crew of the São Rafael waited for an official to command it.

At about 7am Ladislau Parreira, having been informed by civilians of the situation, sent the second lieutenant Tito de Morais to take command of the São Rafael, with orders for both ships to support the garrison of the barracks. When it became known that on the ship D. Carlos I the crew had begun a mutiny but the officials had entrenched, lieutenant Carlos da Maia and a few civilian sailors left the São Rafael. After some gunfire from which a lieutenant and a ship commander became wounded, the officials gave up control of the D. Carlos I, yielding it to the hands of the republicans.

That was the last unit to join the rebels, which included by then part of the 1st and 16th Artillery Regiment, the naval corps and the three warships. Navy members had joined in large numbers as expected, but many military sections considered sympathisers with the cause hadn't joined. Even so, the republican forces included about 400 men in Rotunda, but 1000 to 1500 in Alcântara counting the naval crews, as well as having managed to take hold of the city's artillery, with most of the ammunition, to which was added the naval artillery. Rotunda and Alcântara were occupied, but concrete plans for the revolution had not yet been decided and the main leaders hadn't yet appeared.

In spite of this, the beginning of the events did not occur favourably for the rebels. The three cannon shots – the accorded signal for the civilians and military to advance – did not take place. Only a shot was heard and the admiral Cândido dos Reis, expecting the signal to take command of the warships, was informed by officials that everything had failed, which prompted him to retire to his sister's house. The next morning his dead body was found in Arroios. In desperation, he had committed suicide by a shot to the head.

Meanwhile, in Rotunda, the apparent calm in the city was so discouraging to the rebels that officials preferred to give up. Sá Cardoso, Palla and other officials retired to their houses, but Machado Santos stayed and assumed command. This decision proved fundamental to the success of the revolution.

The government forces

The military garrison of Lisbon was composed by four infantry regiments, two cavalry regiments and two light infantry battalions, with a theoretical total of 6982 men. However, in practice, there were other useful units in military outposts used for lookout and general police duties, especially in factories in Barreiro due to the bout of strikes and syndicalist activity that had been ongoing since September .[66]

Ever since the previous year the government forces had a plan of action, drawn up by order of the military commander of Lisbon, General Manuel Rafael Gorjão Henriques. When, on the evening of the 3rd, the president of the Council of Ministers Teixeira de Sousa informed him of the imminence of a revolt, a prevention order was soon sent to the garrisons in the city. The units of Artillery 3 and Light Infantry 6 were called from Santarém, while Infantry 15 was called from Tomar.

As soon as news of the revolt were received, the plan was put into practice: the 1st Infantry, 2nd Infantry, 2nd Light Infantry and 2nd Cavalry regiments and the artillery battery of Queluz, went to the Palace of Necessidades to protect the king, while Infantry 5 and Light Infantry 5 moved to Rossio Square, with the mission to protect the military headquarters.

As for the police force and municipal guards, they were distributed through the city as set out in the plan, intended to protect strategic points such as Rossio Railway Station, the gas factory, the Portuguese mint, the postal building, the Carmo barracks, the ammunition depot in Beirolas and the residence of the president of the Council of Ministers, where the government had assembled. Little is known of the fiscal guard (a total of 1397 units), only that a few soldiers were with the troops in Rossio. The civil police (total of 1200 units) stayed in the squads. This inaction decreased the effective government forces by approximately 2600 units.[67]

The fighting

The fact that some units of the monarchical side sympathised with the republicans, combined with the abandonment by the rebels of the original plan of action, opting instead for entrenchment in Rotunda and Alcântara, led to a situation of impasse throughout 4 October, with all manner of rumours about victories and defeats spreading through the city.

As soon as news of the concentration of rebels in Rotunda were received, the military command of the city organised a detachment to break them up. The column, under the command of Colonel Alfredo Albuquerque, was formed by units that had been removed from the protection of the Palace of Necessidades: Infantry 2, Cavalry 2 and the mobile battery of Queluz. The latter included the colonial war hero Henrique Mitchell de Paiva Couceiro. The column advanced until near the prison, where it assumed combat positions. However, before these were completed, the column was attacked by rebels. The attack was repelled but resulted in a few wounded men, several dead pack animals and the scattering of about half the infantry. Paiva Couceiro responded with cannons and the infantry that remained during 45 minutes, ordering an attack that was carried out by around 30 soldiers, but which was beaten with some casualties. Continuing the gunfire, he ordered a new attack, but only 20 soldiers followed the order. Thinking that he had found the right time to assault the barracks of Artillery 1, Paiva Couceiro requested reinforcement to the division's command. However, he received the perplexing order to retreat.[68]

Meanwhile, a column had been formed with the intention to attack simultaneously the rebels in Rotunda, a plan that was never carried out because of the order to retreat. The column reached Rossio in the evening without having joined combat. This inaction was not caused by the incompetence of its commander, General António Carvalhal, as would become clear the next day, when he was named chief of the Military Division for the republican government: he had changed sides.

The reinforcements of the province, expected by the government throughout 4 October, never arrived. Only the units already mentioned and called for the preventive measures received orders to advance. Since the beginning of the revolution, members of the Carbonária had disconnected the telegraphy lines, thus impeding communication with units outside Lisbon. In addition, the rebels had cut off the railway tracks,[69] which meant that even if the troops follow the orders to advance, they would never arrive on time. Reinforcements from the Setúbal peninsula were also unlikely to arrive, since the Tagus was controlled by rebel ships.[70]

Towards the end of the day the situation was difficult for the monarchical forces: the rebel ships were docked beside the Palace Square and the cruiser São Rafael opened fire on the ministry buildings[71][72] in the bewildered sight of the Brazilian diplomatic corps aboard battleship São Paulo, whose passenger list included the elected president Hermes da Fonseca.[73] This strike undermined the morale of the forces in Rossio.

The king's departure from Lisbon

After the dinner with Hermes da Fonseca, D. Manuel II returned to the Palace of Necessidades, keeping the company of a few officials. They were playing bridge[74] when the rebels began an attack on the building.[75] The king attempted some phone calls but, finding that the lines had been cut, managed only to inform the Queen mother, who was in Pena National Palace, about the situation. Soon afterwards, groups of units that were loyal to the king arrived at the scene and managed to defeat the attacks of the revolutionaries.

At 9 o'clock the king received a phone call from the president of the Council, advising him to find refuge in Mafra or Sintra, since the rebels were threatening to bomb the Palace of Necessidades. D.Manuel II refused to leave, saying to those present: "Go if you want, I'm staying. Since the constitution doesn't appoint me any role other than of letting myself be killed, I will abide by it."[76]

With the arrival of the mobile battery from Queluz, the pieces were arranged in the palace gardens so that they could bombard the quarters of the revolutionary sailors, which were located at no more than 100 metres from the palace. However, before they had time to start, the commander of the battery received the order to cancel the bombing and join the forces that were leaving the palace, integrated into the column that would attack the rebels in Artillery 1 and the Rotunda. At around midday the cruisers Adamastor and São Rafael, which had anchored in front of the sailors' quarters an hour previously, started the bombardment of the Palace of Necessidades, an action which served to demoralise the present monarchical forces. The king took refuge in a small house in the palace's park, where he could ring Teixeira de Sousa, since the revolutionaries had only cut the special state telephone lines and not the general network. The king ordered the prime minister to send the battery from Queluz to the palace to impede the debarkation of the sailors, but the prime minister replied that the main action was happening in Rotunda and all the troops that were there were needed. Taking into account that the available troops were not sufficient to defeat the rebels in Rotunda, the minister made it obvious to the king that it would be more convenient to retire to Sintra or Mafra so that the stationed forces of the palace could reinforce the troops in Rotunda.

At two o'clock the vehicles with D. Manuel II and his advisors set out to Mafra, where the Practical School of Infantry would provide enough forces to protect the monarch. While approaching Benfica the king liberated the municipal guard squad that escorted him so that they could join the fight against the rebels. The escort arrived in Mafra at around four o'clock in the afternoon, but then discovered a problem: due to the holidays, the Practical School contained only 100 soldiers, as opposed to the 800 that were expected, and the person in charge, Colonel Pinto da Rocha, admitted to not having the means to protect the king.[77] In the meantime, Counsellor João de Azevedo Coutinho arrived and advised the king to call to Mafra the queens D. Amélia and D. Maria Pia (respectively, the king's mother and grandmother), who were in the palaces of Pena and Vila in Sintra, and to prepare to continue on to Porto, where they would organise a resistance.

In Lisbon, the king's departure did not bring a large advantage since the majority of the liberated troops did not follow the orders to march to Rossio Square to prevent the concentration of rebel artillery in Alcântara.

The triumph of the revolution

On the night of 4 October the morale was low amongst the monarchical troops stationed in Rossio Square, due to the constant danger of being bombarded by the naval forces and not even the Couceiro's batteries, strategically placed there, could bring them comfort. In the headquarters there were discussions about the best position to bomb the Rotunda. At 3am, Paiva Couceiro departed with a mobile battery, escorted by a municipal guard squad, and positioned himself in Castro Guimarães Garden, in Torel, waiting for daybreak. When the forces in Rotunda began to shoot on Rossio, revealing their position, Paiva Couceiro opened fire, causing casualties and sowing confusion amongst the rebels. The bombardment continued with advantage towards the monarchical side, but at eight in the morning Paiva Couceiro received orders to stop fighting, as there would be an armistice of an hour.[78]

Meanwhile, in Rossio, after Paiva de Couceiro's departure with the battery, the morale of the monarchical troops, which considered themselves helpless, deteriorated even more due to the threats of bombardment by the naval forces.[79] Infantry 5 and some members of Light Infantry 5 insisted that they would not be opposed to the debarkation of the sailors. Confronted with this fraternisation with the enemy, the commanders of these formations went to the headquarters, where they were surprised with the news of the armistice.

| “ | Proclaimed by major military forces, all armed and aided by the popular contest, the Republic now has its first day of History. The unfolding of the events, by the time of writing, can feed all hope for a definite triumph. […] It's hard to imagine the enthusiasm that runs through the city. The people are truly crazy with satisfaction. It could be said that the entire population of Lisbon is on the streets, cheering the republic. | ” |

| — O Mundo, 5 October 1910[80] | ||

The new German representative, who had arrived two days earlier, had taken rooms in Hotel Avenida Palace, which housed many other foreigners. The proximity of the building to the combat zone represented a great danger which prompted the diplomat to intervene. He addressed himself to the General Gorjão Henriques to request a cease-fire that would enable him to evacuate foreign citizens. Without notifying the government, and perhaps hoping to buy time for the arrival of the reinforcements from the province, the general agreed.[81]

The German diplomat, accompanied by a man with a white flag, went to the Rotunda to discuss the armistice with the revolutionaries. The latter, however, at the sight of the white flag, mistakenly thought that the king's forces were surrendering, prompting them to join in crowds a celebration of the new republic. In the square, Machado Santos initially refuses to accept the armistice, but eventually accepts it after the insistence of the diplomat. Then, seeing the massive popular support for the revolution in the streets, he recklessly goes to the headquarters, accompanied by many populars and several officers who left the position in the Rotunda.

The situation in Rossio, with the pouring of the populars onto the streets, was very confusing but advantageous to the republicans, given the obvious public support. Machado Santos spoke to General Gorjão Henriques and invited him to keep the role of commandant of the division, but he refused. António Carvalhal, known to be a republican sympathiser, then received the command instead. Soon afterwards, at 9 o'clock in the morning, the Republic was proclaimed by José Relvas[82] from the balcony of the Paços do Concelho. A provisional government was then nominated, presided by members of the Portuguese Republican Party, with the purpose to govern the nation until a new constitution was approved.

The revolution incurred in dozens of casualties. The exact number is unknown, but it is recognised that, until 6 October, there were 37 mortal victims of the revolution registered in the morgue. Several injured turned up at the hospitals, some of whom would later die. For example, out of 78 injured victims checked into Hospital de São José, 14 died in the following days.[83]

The royal family's exile

In Mafra, on the morning of 5 October, the king was looking for a way to reach Porto, an action that would be very difficult to carry out due to the almost non-existence of an escort and the innumerable revolutionary hubs spread throughout the country. At around midday the President of the Municipal Chamber of Mafra received a message from the new civil governor ordering the switching to a republican flag. Soon afterwards the commander of the Practical School of Infantry also received a telegram from his new commander informing him of the current political situation. The position of the royal family was becoming unsustainable.

The solution appeared when news arrived that the royal yacht Amélia had anchored nearby, in Ericeira. By 2am the yacht had collected from Cascais Citadel the king's uncle and heir to the throne, D. Afonso, and knowing that the king was in Mafra, had moved to Ericeira, as it was the closest anchorage. D. Manuel II, knowing that with the proclamation of the Republic he would be imprisoned, decided to go to Porto. The royal family and some company departed for Ericeira where, by means of two fishing ships and in the presence of curious civilians, they embarked on the royal yacht.[84]

Once on board, the king wrote to the prime minister:

My dear Teixeira de Sousa, forced by the circumstances I find myself obliged to embark on the royal yacht "Amélia". I'm Portuguese and will always be. I have the conviction of having always fulfilled my duties as King in all the circumstances and of having put my heart and my life on the service to the Country. I hope that it, convinced of my rights and my dedication, will recognise this! Viva Portugal! Give this letter all the publicity you can.

After ensuring that the letter would reach its destination, the king announced that he wanted to go to Porto. He met with an advising council, the officials and part of the escort. The commander João Agnelo Velez Caldeira Castelo Branco and the chief officer João Jorge Moreira de Sá opposed the opinion of the monarch, claiming that if Porto turned them away, they would not have enough fuel to reach a different anchorage. Despite the insistence of D. Manuel II, the chief officer argued that they carried on board the whole royal family, so his main duty was to save their lives. In the end, the chosen port was Gibraltar. Once there, the king found out that Porto had also joined the republican cause. D. Manuel sent orders that the ship, being legally the Portuguese State's property, be returned to Lisbon. The deposed king would live out the rest of his life in exile.[86]

The first steps of the Republic

Performance of the Provisional Government

On 6 October 1910, newspaper Diário do Governo announced: "To the Portuguese people —Constitution of the Provisional Government of the Republic — Today, 5 October 1910, at eleven o'clock in the morning, was proclaimed the Portuguese Republic in the grand hall of the Palaces of Lisbon Municipality, after the end of the National Revolution movement. The Provisional Government was constituted immediately: Presidency, Dr Joaquim Teófilo Braga. Interior, Dr. António José de Almeida. Justice, Dr. Afonso Costa. Treasure, Basílio Teles. War, António Xavier Correia Barreto. Navy, Amaro Justiniano de Azevedo Gomes. Foreign, Dr. Bernardino Luís Machado Guimarães. Public Works, Dr. António Luís Gomes."[87]

By decree on 8 October, the Provisional Government determined the new names of the ministries, with the most important changes being made to the ministries of the Kingdom, Treasure and Public Works, which were renamed ministries of Interior, Finances and Development.[88] However, Basílio Teles refused the position and, on the 12th, it was given to José Relvas.[89] On 22 November, Brito Camacho entered government after the departure of António Luís Gomes, appointed Portuguese ambassador in Rio de Janeiro.[90]

| “ | The ministers [of the Provisional Government], inspired by a high sense of patriotism, always sought to reflect in their actions the highest and most pressing aspirations of the old Republican Party, in terms of reconciling the permanent interests of society with the new order of things, inevitably derived from the revolution. | ” |

| — Teófilo Braga, 21-06-1911[91] | ||

During its time of power, the Provisional Government took a series of important measures that had long-lasting effects. To calm tempers and make reparations with the victims of the monarchy, a broad amnesty was granted for crimes against the security of the State, against religion, of disobedience, of forbidden weaponry usage, etc.[92] The Catholic Church resented the measures taken by the Provisional Government. Among these were the expulsion of the Society of Jesus and other religious orders of the Regular clergy, the closure of convents, the prohibition of religious teaching in schools, the abolition of the religious oath in civil ceremonies and a secularisation of the State by the separation of Church and State. Divorce was institutionalised,[93] as were the legality of civil marriage, the equality of the marriage rights of men and women, the legal regulation of "natural children";[94] the protection of childhood and old age, the reformulation of the Press laws, the elimination of royal and noble ranks and titles and the acknowledgment of right to strike action.[95] The Provisional Government also opted for the dissolution of the then municipal guards of Lisbon and Porto, creating instead a new public body of defence an order, the National Republican Guard. For the colonies, new legislation was created in order to grant autonomy to overseas territories, an essential condition for their development. The national symbols were modified – the flag and the national anthem —, a new monetary unit was adopted – the escudo, equivalent to a thousand réis[96] – and even the Portuguese orthography was simplified and appropriately regulated through the Orthographic Reform of 1911.[97]

The Provisional Government enjoyed extensive power until the official launch of the National Constituting Assembly on 19 June 1911, following the election of 28 May of the same year.[98] At that time, the president of the Provisional Government, Teófilo Braga, handed over to the National Constituting Assembly the powers he had received on 5 October 1910. Nevertheless, the Assembly approved with acclaim the proposal presented by their president, Anselmo Braamcamp Freire to the congress: "The National Constituting Assembly confirms, until future deliberation, the functions of the Executive Power to the Provisional Government of the Republic".

Two months later, with the approval of the Political Constitution of the Portuguese Republic and the election of the first constitutional president of the Republic – Manuel de Arriaga – on 24 August, the Provisional Government presented its resignation, which was accepted by the president of the republic on 3 September 1911, marking the end of a government term of more than 10 months[99] and the beginning of the First Portuguese Republic.

Modification of national symbols

With the establishment of the Republic, the national symbols were modified. By a Provisional Government decree dated 15 October 1910, a committee was appointed to design the new symbols.[100] The modification of national symbols, according to historian Nuno Severiano Teixeira, emerged from the difficulty that republicans faced with representing the Republic:

| “ | In a monarchy the king has a physical body and is therefore a recognisable person, recognised by citizens. But a republic is an abstract idea. | ” |

| — Nuno Severiano Teixeira, [101] | ||

The flag

.jpg)

In relation to the flag, there were two inclinations: one of keeping the blue and white colours, traditional of Portuguese flags, and another of using "more republican" colours: green and red. The committee's proposal suffered several alterations, with the final design being rectangular, with the first two fifths closest to the flagpole to be green, and the three remaining fifths, red.[102][103] Green was chosen because it was considered the "colour of hope", while red was chosen as a "combative, hot, virile" colour.[104] The project of the flag was approved by the Provisional Government by vote on 19 November 1910. On 1 December was celebrated the Feast of the Flag in front of the Municipal Chamber of Lisbon.[105] The National Constituting Assembly promulgated the adoption of the flag on 19 June 1911.[106]

The national anthem

On 19 June 1911 the National Constituting Assembly proclaimed A Portuguesa as the national anthem,[107][108] replacing the old anthem Hymno da Carta in use since May 1834, and its status as national symbol was included in the new constitution. A Portuguesa was composed in 1890, with music by Alfredo Keil and lyrics by Henrique Lopes de Mendonça, in response to the 1890 British Ultimatum.[109] Because of its patriotic character, it had been used, with slight modifications, by the rebels of the 1891 uprising[110] in a failed attempt at a coup d'état to establish a republic in Portugal, an event which caused the anthem to be forbidden by the monarchic authorities.

A Portuguesa (1910–present)

Although proclaimed national anthem in 1911, the official version used today in national civil and military ceremonies and during visits of foreign heads of state[111] was only approved on 4 September 1957.[112]

The bust

The official bust of the Republic was chosen through a national competition promoted by Lisbon's city council in 1911,[114] in which nine sculptors participated.[115][116] The winning entry was that of Francisco dos Santos[117] and is currently exposed in the Municipal Chamber. The original piece is found in Casa Pia, an institution from which the sculptor was alumnus. There is another bust that was adopted as the face of the Republic, designed by José Simões de Almeida in 1908.[118] The original is found in the Municipal Chamber of Figueiró dos Vinhos. The model for this bust was Ilda Pulga, a young shop employee from Chiado.[119][120] According to journalist António Valdemar, who, when he became president of the National Academy of Art asked the sculptor João Duarte to restore the original bust:

| “ | Simões found the face of the girl funny and invited her to be a model. The mother said that she'd allow it but with two conditions: that she would be present in the sessions and that the daughter would not be undressed. | ” |

| — António Valdemar | ||

The bust shows Republic wearing a Phrygian cap, influence of the French Revolution. Simões' bust was soon adopted by Freemasonry and used in the funerals of Miguel Bombarda and Cândido dos Reis, but when the final contest took place, despite its relative popularity, it was second place to the bust by Francisco dos Santos.

Anticlericalism

Republican leaders adopted a severe and highly controversial policy of anticlericalism.[121] At home, the policy polarised society and lost the republic potential supporters, and abroad it offended American and European states which had their citizens engaged in religious work there, adding substantially to the republic's bad press.[122] The persecution of the church was so overt and severe that it drove the irreligious and nominally religious to a new religiosity and gained the support of Protestant diplomats such as the British, who, seeing their citizens' religious institutions in a grave dispute over their rights and property, threatened to deny recognition of the young republic.[123] The revolution and the republic which it spawned were essentially anticlerical and had a "hostile" approach to the issue of church and state separation, like that of the French Revolution, the Spanish Constitution of 1931 and the Mexican Constitution of 1917.[124]

Secularism began to be discussed in Portugal back in the 19th century, during the Casino Conferences in 1871, promoted by Antero de Quental. The republican movement associated the Catholic Church with the monarchy, and opposed its influence in Portuguese society. The secularisation of the Republic constituted one of the main actions to be taken in the political agenda of the Portuguese Republican Party and the Freemasonry. Monarchists in a last-ditch effort sought to outflank the republicans by enacting anticlerical measures of their own, even enacting a severe restriction on the Jesuits on the day before the revolution.[122]

Soon after the establishment of the Republic, on 8 October 1910, Minister for Justice Afonso Costa reinstated Marquess of Pombal's laws against the Jesuits, and Joaquim António de Aguiar's laws in relation to religious orders.[125][126] The Church's property and assets were expropriated by the State. The religious oath and other religious elements found in the statutes of the University of Coimbra were abolished, and matriculations into first year of the Theology Faculty were cancelled, as were places in the Canon law course, suppressing the teaching of Christian doctrine. Religious holidays turned into working days, keeping however the Sunday as a resting day for labour reasons. As well as that, the Armed forces were forbidden from participating in religious solemn events. Divorce and family laws were approved which considered marriage as a "purely civil contract"[127][128]

Bishops were persecuted, expelled or suspended from their activities in the course of the secularisation. All but one were driven from their dioceses.[129] the property of clerics was seized by the state, wearing of the cassock was banned, all minor seminaries were closed and all but five major seminaries.[129] A law of 22 February 1918 permitted only two seminaries in the country, but they had not been given their property back.[129] Religious orders were expelled from the country, including 31 orders comprising members in 164 houses (in 1917 some orders were permitted to form again).[129] Religious education was prohibited in both primary and secondary school.[129]

In response to the several anticlerical decrees, Portuguese bishops launched a collective pastoral defending the Church's doctrine, but its reading was prohibited by the government. In spite of this, some prelates continued to publicise the text, among which was the bishop of Porto, António Barroso. This resulted in him being called to Lisbon by Afonso Costa, where he was stripped from his ecclesiastic functions.

The secularisation peaked with the Law of Separation of the State and the Church on 20 April 1911,[130] with a large acceptance by the revolutionaries. The law was only promulgated by the Assembly in 1914, but its implementation was immediate after the publishing of the decree. The Portuguese Church tried to respond, classifying the law as "injustice, oppression, spoliation and mockery", but without success. Afonso Costa even predicted the eradication of Catholicism in the space of three generations.[131] The application of the law began on 1 July 1911, with the creation of a "Central Commission".[132] As one commentator put it, "ultimately the Church was to survive the official vendetta against organized religion".[133]

On 24 May 1911, Pope Pius X issued the encyclical Iamdudum which condemned the anticlericals for their deprivation of religious civil liberties and the "incredible series of excesses and crimes which has been enacted in Portugal for the oppression of the Church."[134]

International recognition

One of the first great preoccupations of the new republican government was being recognised by other nations. In 1910, the vast majority of European states were monarchies. Only France, Switzerland and San Marino were republics. For this reason, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Provisional Government, Bernardino Machado, directed his agenda exercising extreme prudence,[135] leading him, on 9 October 1910, to communicate to diplomatic representatives in Portugal that the Provisional Government would honour all the international commitments assumed by the previous regime.[136]

Since marshal Hermes da Fonseca personally witnessed the full process of transition of the regime, having arrived in Portugal on an official visit when the country was still a monarchy and left when it was a republic,[137] it is not unusual that Brazil was the first country to recognise de jure the new Portuguese political regime. On 22 October the Brazilian government declared that "Brazil will do all that is possible for the happiness of the noble Portuguese Nation and its Government, and for the prosperity of the new Republic".[138] The next day would be Argentina's turn; on the 29 it was Nicaragua; on the 31, Uruguay; on 16 and 19 November, Guatemala and Costa Rica; Peru and Chile on 5 and 19 November; Venezuela on 23 February 1911; Panama on 17 March.[139] In June 1911 the United States declared support.[140]

Less than a month after the revolution, on 10 November 1910, the British government recognised de facto the Portuguese Republic, manifesting "the liveliest wish of His Britannic Majesty to maintain friendly relations" with Portugal.[141] An identical position was taken by the Spanish, French and Italian governments. However, de jure recognition of the new regime only emerged after the approval of the Constitution and the election of the President of the Republic. The French Republic was the first to do it on 24 August 1911,[142] day of the election of the first president of the Portuguese Republic. Only on 11 September did the United Kingdom recognise the Republic, accompanied by Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire,[143] Denmark, Spain, Italy and Sweden. On 12 September, they were followed by Belgium, the Netherlands and Norway; on 13 September, China and Japan; on 15 September, Greece; on 30 September, Russia;[144] on 23 October, Romania; on 23 November, Turkey; on 21 December, Monaco; and on 28 February 1912, Siam. Owing to the tensions created between the young Republic and the Catholic Church, interaction with the Holy See was suspended and the Roman Curia did not recognise the Portuguese Republic until 29 June 1919.

See also

- Anticlericalism

- History of Portugal (1834–1910)

- Lisbon Regicide

- Portuguese First Republic

- Timeline of Portuguese history

References

- ↑ "Implantação da República". Infopédia. 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "A Ditadura de João Franco e a autoria moral e política de D. Carlos". avenidadaliberdade.org. 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "João Franco". Vidas Lusófonas. 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "1ª Republica – Dossier temático dirigido às Escolas" (PDF). Rede Municipal de Bibliotecas Públicas do concelho de Palmela. 30 August 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "5 de Outubro de 1910: a trajectória do republicanismo". In-Devir. 30 August 2010. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011.

- ↑ A este propósito ver Quental, Antero de (1982). Prosas sócio-políticas ;publicadas e apresentadas por Joel Serrão (in Portuguese). Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda. p. 248. citado na secção "O Partido Republicano Português" deste artigo.

- ↑ "Primeira República – Biografia de João de Canto e Castro". www.leme.pt. 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Constituição de 1911 – Infopédia". www.infopedia.pt. 9 September 2010.

- ↑ "Política: O Ultimato Inglês e o 31 de Janeiro de 1891". Soberania do Povo. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Ultimatum de 1890". Almanaque da República. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Trinta e Um de Janeiro de 1891". Infopédia. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ Paulo Vicente. "O 5 de Outubro de 1910: a trajectória do republicanismo". In-Devir. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

O Partido Republicano [...] soube capitalizar em seu favor a crise económica que se abateu sobre o país e o descrédito em que se encontravam os partidos do rotativismo monárquico. Num tom violento e populista, desdobrava-se em violentas críticas ao rei e aos seus governos, que identificava com a "decadência nacional". Ao longo da década de 80 do século XIX, a expressão eleitoral do Partido Republicano foi crescendo e, com ela, cresceu também o clima de exaltação patriótica.

- ↑ página do Governo da República Portuguesa (2009). "Chefes do Governo desde 1821". Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ↑ "Antigos Presidentes: António José de Almeida". Página Oficial da Presidência da República Portuguesa. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ Santos, Maria Emília Madeira (1983). Silva Porto e os problemas da África portuguesa no século XIX. Série Separatas / Centro de Estudos de Cartografia Antiga (in Portuguese). 149. Coimbra: Junta de Investigações Científicas do Ultramar. p. 27.

- ↑ KmMad. "Silva Porto: do Brasil a África" (in Portuguese). Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ↑ Pélissier, René (2006). Campanhas coloniais de Portugal, 1844–1941. Estampa. p. 27. ISBN 9723323052.

- ↑ Nuno Severiano Teixeira. "Política externa e política interna no Portugal de 1890: o Ultimatum Inglês" (PDF). Análise Social – Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "A revolta de 31 de Janeiro de 1891". Livra Portugal. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "1891: Revolta militar de 31 de Janeiro, no Porto". Farol da Nossa Terra. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ Carlos Loures. "31 de Janeiro (Centenário da República)". Retrieved 4 September 2010.

O levantamento militar de 31 de Janeiro de 1891, no Porto, foi a primeira tentativa de derrube do regime monárquico pela força. Desde 1880, quando das comemorações do tricentenário de Camões, que, em crescendo, o ideal republicano e a capacidade de organização dos seus militantes, inclusive no seio das Forças Armadas, fazia prever uma rebelião. [...] Tendo fracassado no plano militar [...], o movimento de 31 de Janeiro foi, por assim dizer, uma vitória histórica, pois transformou-se numa data fetiche, num símbolo, para os republicanos que, dezanove anos depois triunfariam.

- ↑ Quental, Antero de (1982). Prosas sócio-políticas. publicadas e apresentadas por Joel Serrão (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda. p. 248.

- ↑ Lourenço Pereira Coutinho. "História do Partido Republicano Português – Parte I". Centenário da República – vamos fazer história!. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Rodrigues de Freitas, Primeiro Deputado da República". Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Ser republicano, por 1890, 1900 e 1910, queria dizer ser contra a Monarquia, contra a Igreja e os Jesuítas, contra a corrupção política e os partidos monárquicos. [...] A tendência geral era para se conceder à palavra República algo de carismático e místico, e para acreditar que bastaria a sua proclamação para libertar o País de toda a injustiça e de todos os males". A. H. de Oliveira Marques (coord.). "Portugal – Da Monarquia para a República" in Nova História de Portugal, Volume XI, Lisboa, Editorial Presença, 1991, p. 372. cit in Artur Ferreira Coimbra. Paiva Couceiro e a Contra-Revolução Monárquica (1910–1919). Braga, Universidade do Minho, 2000. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ "Nogueira (José Félix Henriques)". Portugal – Dicionário Histórico. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Igreja e Estado". Almanaque da República. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Teófilo Braga, em carta escrita na sua juventude, prefigura já um implacável anticlericalismo: "O padre há-de ser sempre uma sombra que se não dissipa nem à força de muita luz; envolve-nos, deixa-nos na solidão de nós mesmos, no tédio do vazio, quando a alegria transpira e ri lá fora por toda a parte; torna-nos pouco a pouco a vida um remorso, a esperança um nada impalpável, porque só no-la prometem para além da campa" Homem, A. Carvalho (1989). A Ideia Republicana em Portugal : o Contributo de Teófilo Braga (in Portuguese). Coimbra: Minerva. p. 172. cit. in Queirós, Alírio (2009). A Recepção de Freud em Portugal (in Portuguese). Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra. p. 28.

- ↑ "Vasco da Gama e Luís de Camões". Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ "O tricentenário de Camões". Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ "1 de Fevereiro: O dia em que a Monarquia morreu". Mundo Portugues. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Quais os motivos que estão na base do regicídio?". Departamento de Bibliotecas e Arquivos, da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "João Franco". Portugal – Dicionário Histórico. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Governo de João Franco". www.iscsp.utl.pt. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Do visconde de esgrima, as armas que mataram o rei...". A Bola. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ D. Manuel II. "O Atentado de 1 de Fevereiro. Documentos" (PDF). Associação Cívica República e Laicidade, pp. 3 e 4. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Percurso histórico do Regicídio". Hemeroteca Digital. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "4ª Dinastia D. Carlos – o "Martirizado" reinou de 1889 – a 1908". www.g-sat.net. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Regicídio no Terreiro do Paço". Almanaque da República. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "O atentado horrorizará a Europa e o mundo. O facto de não ser um acto isolado de um anarquista ou de um par de fanáticos, mas um conluio organizado, chocará particularmente a comunidade internacional. Imagens das campas dos regicidas cobertas de flores são publicadas na imprensa inglesa com o título "Lisbon's Shame" (A vergonha de Lisboa)." In NOBRE, Eduardo. "O regicídio de 1908" in revista Única, 2004, p. 40.

- ↑ Bern, Stéphane (1999). Eu, Amélia, Última Rainha de Portugal (in Portuguese). Porto: Livraria Civilização Editora. p. 172.

- ↑ Proença, Maria Cândida (2006). D. Manuel II: Colecção "Reis de Portugal" (in Portuguese). Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores. p. 100.

- ↑ Saraiva, José Hermano (1983). História de Portugal (in Portuguese). 6. Lisboa: Publicações Alfa. p. 112..

- ↑ "Governo de Acalmação". Almanaque da República. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Congresso republicano". Almanaque da República. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Cândido dos Reis". Almanaque da República. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Instituições – Carbonária". Almanaque da República. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Miguel Bombarda". Almanaque da República. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Instituições – Monarquia terminal". Almanaque da República. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Afonso Costa – 5 de Outubro de 1910". www.citi.pt. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "5 de Outubro de 1910". Olho Vivo. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "A revolução do 5 de Outubro de 1910". Tinta Fresca. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Assassinato de Miguel Bombarda". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Visita a Portugal do Presidente da República do Brasil, Marechal Hermes da Fonseca". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "D. Manuel de Bragança parte para o exílio". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "O 5 de Outubro de 1910. Dia 3 Out.". Centenário da República. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Quartel-general nos Banhos de S. Paulo". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Reunião da Rua da Esperança". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Relvas, José (1977). Memórias Políticas (in Portuguese). Lisboa: Terra Livre. p. 112.

- ↑ "Machado Santos prepara o assalto a Infantaria 16". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Medina, João (2004). "Monarquia Constitucional (II) – A República (I)". História de Portugal (in Portuguese). XX, XII. Amadora: Edita Ediclube, Edição e Promoção do Livro. p. 445. ISBN 9789727192694.

- ↑ "Quartel de Compolide" in Da Conspiração ao 5 de Outubro de 1910

- ↑ "O 5 de Outubro de 1910. Dia 4 Out.". Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações do Centenário da República. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Quartel do Corpo de Marinheiros de Alcântara" in Da Conspiração ao 5 de Outubro de 1910

- ↑ "ANTIGOS PRESIDENTES: Mendes Cabeçadas – Página Oficial da Presidência da República Portuguesa". Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ↑ "Alastra o surto de greves". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ David Ferreira, "Outubro de 1910, 5 de" in Joel Serrão (dir.) Dicionário de História de Portugal. Porto, Livraria Figueirinhas, 1985, vol. IV, pp. 500–504

- ↑ Amadeu Carvalho Homem. "República: A revolução no seu "dia inicial"". Público. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ↑ "Paiva Couceiro bombardeia a Rotunda e a Armada anuncia desembarque". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ↑ "Cruzador D. Carlos passa-se para os republicanos". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Armada bombardeia o Rossio". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Cruzadores S. Rafael e Adamastor bombardeiam o Palácio das Necessidades". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Visita a Portugal do Presidente da República do Brasil, Marechal Hermes da Fonseca". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "O rei foge para Mafra". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Ordem para o bombardeamento do Palácio das Necessidade". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ Martins, Rocha (1931–1933). D. Manuel II: História do seu Reinado e da Implantação da República (in Portuguese). Lisbon: edição do autor. p. 521.

- ↑ Martínez, Pedro Soares (2001). A República Portuguesa e as Relações Internacionais (1910–1926) (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Verbo. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9722220349.

- ↑ "A noite de 4 para 5 de Outubro". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Armada bombardeia o Rossio". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Notícias da Proclamação da República em Portugal". Capim Margoso. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Encarregado de negócios da Alemanha pede armistício e precipita a vitória republicana". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "José Relvas proclamou a República a 5 de Outubro de 1910". RTP. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Vítimas da revolução". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "A juga do rei". Guia do concelho de Mafra. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Martins, Rocha. op. cit. p. 583.

- ↑ Serrão, Joaquim Veríssimo (1997). História de Portugal: A Primeira República (1910–1926) (in Portuguese). IX. Lisbon: Editorial Verbo. p. 39.

- ↑ Diário do Governo de 6 de outubro de 1910, cit. in David Ferreira, "Governo Provisório Republicano" in Dicionário de História de Portugal, direcção de Joel Serrão. Porto, Livraria Figueirinhas, 1985, vol. III, p. 142.

- ↑ "Governo Provisório: de 5 de Outubro de 1910 a 3 September1911. 334 dias". Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas – Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Teófilo Braga, em entrevista ao jornal Dia de 2 de abril de 1913, referiu: "Esse sujeito [José Relvas], logo nos primeiros dias da revolução apresentou-se-nos no conselho de ministros e disse: 'Como o Basílio Teles não vem para as finanças, eu queria ficar no lugar dele.' Eu fiquei mesmo parado, a olhar para o Bernardino [Machado], pasmado do impudor. [...] Mas o homem depois tornou-se a impor [...], e ficou ministro das Finanças" in Carlos Consiglieri (org). Teófilo Braga e os republicanos. Lisboa, Vega, 1987

- ↑ "Proclamação da República nos Paços do Concelho de Lisboa e anúncio do Governo Provisório". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Teófilo Braga discursando perante a Assembleia Nacional Constituinte, cit. in David Ferreira, "Governo Provisório Republicano" in Dicionário de História de Portugal, direcção de Joel Serrão. Porto, Livraria Figueirinhas, 1985, vol. III, p. 144.

- ↑ "Amnistia". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Promulgada a Lei do Divórcio". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Leis da Família". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Direito à greve". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Trigueiros, António Miguel (2003). A grande história do escudo português (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Colecções Philae. p. 444.

- ↑ "Uma revolução democrática ou a vitória de extremistas?". Público. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Eleições de 1911 (28 de Maio)". Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas – Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Serrão, Joaquim Veríssimo. op. cit. p. 141.

- ↑ "Bandeira Nacional". Página Oficial da Presidência da República Portuguesa. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Um busto e um hino consensuais – e uma bandeira polémica". Público. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Evolução da bandeira nacional". Arquivo Histórico do Governo de Portugal. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ António Martins. "Bandeira de Portugal". www.tuvalkin.web.pt. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Bandeira Nacional". Arquivo Histórico do Governo de Portugal. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Símbolos da República". Almanaque da República. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Decreto que aprova a Bandeira Nacional". Arquivo Histórico do Governo de Portugal. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Diário da Assembleia Nacional Constituinte – 1911". Assembleia da República. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Decreto da Assembleia Nacional Constituinte de 19 de Junho" (PDF). Página Oficial da Presidência da República Portuguesa. 19 June 1911. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ↑ "A Portuguesa (hino)". Infopédia. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Hino Nacional". Página Oficial da Presidência da República Portuguesa. 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ↑ "Antecedentes históricos do Hino Nacional". Arquivo Histórico de Portugal. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Resolução do Conselho de Ministros" (PDF). Diário da República. 4 September 1957. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Trigueiros. op. cit. pp. 93 e 139.

- ↑ "Bustos da República". Correios de Portugal. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "A República começou por perder a cabeça a concurso –". Diário de Notícias. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Busto da República não deve ser mudado, dizem escultores". Publico. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Busto da República – Francisco dos Santos". Assembleia da República. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Busto da República da autoria de Simões de Almeida (sobrinho)". Assembleia da República. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Vale a pena conhecer... a história do busto da República (Ilga Pulga)". Chão de Areia. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Descendente de "musa" inspiradora do busto da República imagina que seria "mulher atrevida"". publico.pt. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ↑ Wheeler, Douglas L., Republican Portugal:A Political History, 1910–1926, p. 67, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1998

- 1 2 Wheeler, Douglas L., Republican Portugal:A Political History, 1910–1926, p. 68, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1998

- ↑ Wheeler, Douglas L., Republican Portugal:A Political History, 1910–1926, p. 70, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1998

- ↑ Maier, Hans (2004). Totalitarianism and Political Religions. trans. Jodi Bruhn. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 0714685291.

- ↑ "História em Portugal". Jesuítas. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Governo Provisório". www.iscsp.utl.pt. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Separação da Igreja e do Estado em Portugal (I República)". Infopédia. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ A Primeira República (1910–1926): Dossier temático dirigido às Escolas (PDF) (in Portuguese). Palmela: Rede Municipal de Bibliotecas Públicas do Concelho de Palmela. 2009. p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jedin, Hubert, Gabriel Adriányi, John Dolan, The Church in the Modern Age, p. 612, Continuum International Publishing Group, 1981

- ↑ "Aveiro e o seu Distrito – n.º 10 – dezembro de 1970". www.prof2000.pt. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Página Oficial". Santuário de Fátima. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Lei de Separação do Estado e da Igreja". Infopédia. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ Gallagher, Tom, Portugal:A Twentieth-Century Interpretation, p. 22, Manchester University Press ND, 1983

- ↑ IAMDUDUM: ON THE LAW OF SEPARATION IN PORTUGAL Papal Encyclicals Online

- ↑ Serra, João B (1997). Portugal, 1910–1940 : da República ao Estado Novo (PDF) (in Portuguese). pp. 7–8.

- ↑ "Comunicado de Bernardino Machado honrando todos os compromissos internacionais". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "Bernardino Machado apresenta cumprimentos de despedida ao Presidente eleito do Brasil". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "O Brasil reconhece a República Portuguesa". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "O Reconhecimento Internacional da República Portuguesa". Monarquia. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "EUA reconhecem a República". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "Governo britânico reconhece "de facto" a República portuguesa". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "A França reconhece "de jure" a República Portuguesa". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "A Grã-Bretanha reconhece "de jure" a República Portuguesa". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "Reconhecimento internacional". Fundação Mário Soares. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

External links

- OnWar.com, Armed Conflict Events Data Naval Mutiny in Portugal 1910

.png)