Five-prime cap

In molecular biology, the five-prime cap (5′ cap) is a specially altered nucleotide on the 5′ end of some primary transcripts such as precursor messenger RNA. This process, known as mRNA capping, is highly regulated and vital in the creation of stable and mature messenger RNA able to undergo translation during protein synthesis. Mitochondrial[1] and chloroplast mRNA[2] are not capped.

Structure

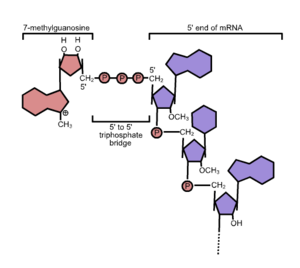

In eukaryotes, the 5′ cap (cap-0), found on the 5′ end of an mRNA molecule, consists of a guanine nucleotide connected to mRNA via an unusual 5′ to 5′ triphosphate linkage. This guanosine is methylated on the 7 position directly after capping in vivo by a methyltransferase.[3][4][5][6] It is referred to as a 7-methylguanylate cap, abbreviated m7G.

In multicellular eukaryotes and some viruses,[7] further modifications exist, including the methylation of the 2′ hydroxy-groups of the first 2 ribose sugars of the 5′ end of the mRNA. cap-1 has a methylated 2'-hydroxy group on the first ribose sugar, while cap-2 has methylated 2'-hydroxy groups on the first two ribose sugars, shown on the right.[8] The 5′ cap is chemically similar to the 3′ end of an RNA molecule (the 5′ carbon of the cap ribose is bonded, and the 3′ unbonded). This provides significant resistance to 5′ exonucleases. (reference needed)

Small nuclear RNAs contain unique 5'-caps. Sm-class snRNAs are found with 5'-trimethylguanosine caps, while Lsm-class snRNAs are found with 5'-monomethylphosphate caps.[9]

In bacteria, and potentially also in higher organisms, some RNAs are capped with NAD+, NADH, or 3'-dephospho-coenzyme A.[10][11]

In all organisms, mRNA molecules can be decapped in a process known as messenger RNA decapping.

Capping process

The starting point for capping with 7-methylguanylate is the unaltered 5′ end of an RNA molecule, which terminates at a triphosphate group. This features a final nucleotide followed by three phosphate groups attached to the 5′ carbon.[3] The capping process is initiated before the completion of transcription, as the nascent pre-mRNA is being synthesized.

- One of the terminal phosphate groups is removed by RNA triphosphatase, leaving a bisphosphate group (i.e. 5'(ppN)[pN]n);

- GTP is added to the terminal bisphosphate by mRNA guanylyltransferase, losing a pyrophosphate from the GTP substrate in the process. This results in the 5′–5′ triphosphate linkage, producing 5'(Gp)(ppN)[pN]n;

- The 7-nitrogen of guanine is methylated by mRNA (guanine-N7-)-methyltransferase, with S-adenosyl-L-methionine being demethylated to produce S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine, resulting in 5'(m7Gp)(ppN)[pN]n (cap-0);

- Cap-adjacent modifications can occur, normally to the first and second nucleotides, producing up to 5'(m7Gp)(ppN*)(pN*)[pN]n (cap-1 and cap-2);[7][8]

- If the nearest cap-adjacent nucleotide is 2'-O-ribose methyl-adenosine (i.e. 5'(m7Gp)(ppAm)[pN]n), it can be further methylated at the N6 methyl position to form N6-methyladenosine, resulting in 5'(m7Gp)(ppm6Am)[pN]n.[3]

The mechanism of capping with NAD+, NADH, or 3'-dephospho-coenzyme A is different. Capping with NAD+, NADH, or 3'-dephospho-conenzyme A is accomplished through an "ab initio capping mechanism," in which NAD+, NADH, or 3'-desphospho-coenzyme A serves as a "non-canonical initiating nucleotide" (NCIN) for transcription initiation by RNA polymerase and thereby directly is incorporated into the RNA product.[10] Both bacterial RNA polymerase and eukaryotic RNA polymerase II are able to carry out this "ab initio capping mechanism."[10]

Targeting

For capping with 7-methylguanylate, the capping enzyme complex (CEC) binds to RNA polymerase II before transcription starts. As soon as the 5′ end of the new transcript emerges from RNA polymerase II, the CEC carries out the capping process (this kind of mechanism ensures capping, as with polyadenylation).[12][13][14][15] The enzymes for capping can only bind to RNA polymerase II, ensuring specificity to only these transcripts, which are almost entirely mRNA.[13][15]

Capping with NAD+, NADH, or 3'-dephospho-coenzyme A is targeted by promoter sequence.[10] Capping with NAD+, NADH, or 3'-dephospho-coenzyme A occurs only at promoters that have certain sequences at and immediately upstream of the transcription start site and therefore occurs only for RNAs synthesized from certain promoters.[10]

Function

The 5′ cap has four main functions:

- Regulation of nuclear export;[16][17]

- Prevention of degradation by exonucleases;[10][18][19][20]

- Promotion of translation (see ribosome and translation);[3][4][5]

- Promotion of 5′ proximal intron excision.[21]

Nuclear export of RNA is regulated by the cap binding complex (CBC), which binds exclusively to 7-methylguanylate-capped RNA. The CBC is then recognized by the nuclear pore complex and exported. Once in the cytoplasm after the pioneer round of translation, the CBC is replaced by the translation factors eIF4E and eIF4G of the eIF4F complex.[6] This complex is then recognized by other translation initiation machinery including the ribosome.[22]

Capping with 7-methylguanylate prevents 5′ degradation in two ways. First, degradation of the mRNA by 5′ exonucleases is prevented (as mentioned above) by functionally looking like a 3′ end. Second, the CBC and eIF4E/eIF4G block the access of decapping enzymes to the cap. This increases the half-life of the mRNA, essential in eukaryotes as the export and translation processes take significant time.

Decapping of a 7-methylguanylate-capped mRNA is catalyzed by the decapping complex made up of at least Dcp1 and Dcp2, which must compete with eIF4E to bind the cap. Thus the 7-methylguanylate cap is a marker of an actively translating mRNA and is used by cells to regulate mRNA half-lives in response to new stimuli. Undesirable mRNAs are sent to P-bodies for temporary storage or decapping, the details of which are still being resolved.[23]

The mechanism of 5′ proximal intron excision promotion is not well understood, but the 7-methylguanylate cap appears to loop around and interact with the spliceosome in the splicing process, promoting intron excision.

See also

References

- ↑ Temperley, Richard J.; Wydro, Mateusz; Lightowlers, Robert N.; Chrzanowska-Lightowlers, Zofia M. (June 2010). "Human mitochondrial mRNAs—like members of all families, similar but different". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1797 (6–7): 1081–1085. PMC 3003153

. PMID 20211597. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.036. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

. PMID 20211597. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.036. Retrieved 12 December 2014. - ↑ Monde, Rita A; Schuster, Gadi; Stern, David B (7 June 2000). "Processing and degradation of chloroplast mRNA". Biochimie. 82 (6–7): 573–582. doi:10.1016/S0300-9084(00)00606-4. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Shatkin, A (December 1976). "Capping of eucaryotic mRNAs". Cell. 9 (4): 645–653. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(76)90128-8. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- 1 2 Banerjee, A K (June 1980). "5'-terminal cap structure in eucaryotic messenger ribonucleic acids". Microbiol Rev. 44 (2): 175–205.

- 1 2 Sonenberg, Nahum; Gingras, Anne-Claude (April 1998). "The mRNA 5′ cap-binding protein eIF4E and control of cell growth". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 10 (2): 268–275. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(98)80150-6.

- 1 2 Marcotrigiano, Joseph; Gingras, Anne-Claude; Sonenberg, Nahum; Burley, Stephen K. (June 1997). "Cocrystal Structure of the Messenger RNA 5′ Cap-Binding Protein (eIF4E) Bound to 7-methyl-GDP". Cell. 89 (6): 951–961. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80280-9. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- 1 2 Fechter, Pierre; Brownlee, George G (1 May 2005). "Recognition of mRNA cap structures by viral and cellular proteins". Journal of General Virology. 86 (5): 1239–1249. doi:10.1099/vir.0.80755-0. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- 1 2 Meyer, Kate D.; Jaffrey, Samie R. (9 April 2014). "The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 15 (5): 313–326. PMC 4393108

. PMID 24713629. doi:10.1038/nrm3785. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

. PMID 24713629. doi:10.1038/nrm3785. Retrieved 12 December 2014. - ↑ Matera, A. Gregory; Terns, Rebecca M.; Terns, Michael P. (March 2007). "Non-coding RNAs: lessons from the small nuclear and small nucleolar RNAs". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 8 (3): 209–220. PMID 17318225. doi:10.1038/nrm2124. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bird JG, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Panova N, Barvík I, Greene L, Liu M, Buckley B, Krásný L, Lee JK, Kaplan CD, Ebright RH, Nickels BE (2016). "The mechanism of RNA 5' capping with NAD(+), NADH and desphospho-CoA". Nature. 535: 444–7. PMC 4961592

. PMID 27383794. doi:10.1038/nature18622.

. PMID 27383794. doi:10.1038/nature18622. - ↑ Cahová, Hana; Winz, Marie-Luise; Höfer, Katharina; Nübel, Gabriele; Jäschke, Andres. "NAD captureSeq indicates NAD as a bacterial cap for a subset of regulatory RNAs". Nature. 519 (7543): 374–377. PMID 25533955. doi:10.1038/nature14020.

- ↑ Cho, E.-J.; Takagi, T.; Moore, C. R.; Buratowski, S. (15 December 1997). "mRNA capping enzyme is recruited to the transcription complex by phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain". Genes & Development. 11 (24): 3319–3326. PMC 316800

. PMID 9407025. doi:10.1101/gad.11.24.3319. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

. PMID 9407025. doi:10.1101/gad.11.24.3319. Retrieved 23 November 2014. - 1 2 Fabrega, Carme; Shen, Vincent; Shuman, Stewart; Lima, Christopher D. (June 2003). "Structure of an mRNA Capping Enzyme Bound to the Phosphorylated Carboxy-Terminal Domain of RNA Polymerase II". Molecular Cell. 11 (6): 1549–1561. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00187-4. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Ho, C. (15 December 1999). "An essential surface motif (WAQKW) of yeast RNA triphosphatase mediates formation of the mRNA capping enzyme complex with RNA guanylyltransferase". Nucleic Acids Research. 27 (24): 4671–4678. doi:10.1093/nar/27.24.4671. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- 1 2 Hirose, Yutaka; Manley, James L (2000). "RNA polymerase II and the integration of nuclear events". Genes Dev. 14 (12): 1415–1429. doi:10.1101/gad.14.12.1415. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Visa, N.; Izaurralde, E.; Ferreira, J.; Daneholt, B.; Mattaj, I. W. (1 April 1996). "A nuclear cap-binding complex binds Balbiani ring pre-mRNA cotranscriptionally and accompanies the ribonucleoprotein particle during nuclear export". The Journal of Cell Biology. 133 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1083/jcb.133.1.5. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Lewis, Joe D.; Izaurralde, Elisa (15 July 1997). "The Role of the Cap Structure in RNA Processing and Nuclear Export". European Journal of Biochemistry. 247 (2): 461–469. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00461.x. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Evdokimova, Valentina; Ruzanov, Peter; Imataka, Hiroaki; Raught, Brian; Svitkin, Yuri; Ovchinnikov, Lev P.; Sonenberg, Nahum (1 October 2001). "The major mRNA-associated protein YB-1 is a potent 5' cap-dependent mRNA stabilizer". The EMBO Journal. 20 (19): 5491–5502. PMC 125650

. PMID 11574481. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.19.5491. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

. PMID 11574481. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.19.5491. Retrieved 23 November 2014. - ↑ Gao, Min; Fritz, David T.; Ford, Lance P.; Wilusz, Jeffrey (March 2000). "Interaction between a Poly(A)-Specific Ribonuclease and the 5′ Cap Influences mRNA Deadenylation Rates In Vitro". Molecular Cell. 5 (3): 479–488. PMC 2811581

. PMID 10882133. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80442-6. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

. PMID 10882133. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80442-6. Retrieved 23 November 2014. - ↑ Burkard, K. T. D.; Butler, J. S. (15 January 2000). "A Nuclear 3'-5' Exonuclease Involved in mRNA Degradation Interacts with Poly(A) Polymerase and the hnRNA Protein Npl3p". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 20 (2): 604–616. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.2.604-616.2000. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Konarska, Maria M.; Padgett, Richard A.; Sharp, Phillip A. (October 1984). "Recognition of cap structure in splicing in vitro of mRNA precursors". Cell. 38 (3): 731–736. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90268-X. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ Kapp, L.D.; Lorsch, J.R. (2004), "The Molecular Mechanics of Eukaryotic Translation" (PDF), Annual Review of Biochemistry, 73 (1): 657–704, PMID 15189156, doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.030403.080419

- ↑ Parker, R.; Sheth, U. (2007), "P Bodies and the Control of mRNA Translation and Degradation" (w), Molecular Cell, 25 (5): 635–646, PMID 17349952, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011

External links

- "RNA Caps". PubMed Medical Subject Heading (MeSH). National Institutes of Health.