4th Army (Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

| 4th Army | |

|---|---|

Armijski đeneral Petar Nedeljković commanded the Yugoslav 4th Army during the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia | |

| Active | 1941 |

| Country |

|

| Branch | Royal Yugoslav Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Corps[lower-alpha 1] |

| Part of | 1st Army Group |

| Engagements | Invasion of Yugoslavia |

| Disbanded | 1941 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Petar Nedeljković |

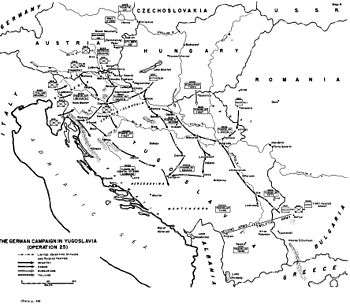

The 4th Army was a Royal Yugoslav Army formation mobilised prior to the German-led Axis invasion of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April 1941 during World War II. It was drawn from the peacetime 4th Army District. When mobilised, it consisted of three divisions, a brigade-strength detachment, one horse cavalry regiment and one independent infantry regiment. It formed part of the 1st Army Group, and was responsible for defending a large section of the Yugoslav–Hungarian border, being deployed behind the Drava river between Varaždin and Slatina.

Despite concerns over a possible Axis invasion, orders for the general mobilisation of the Royal Yugoslav Army were not issued by the government until 3 April 1941, out of fear that this would offend Adolf Hitler and precipitate war. When the invasion commenced on 6 April, the 4th Army was only partially mobilised, and this weakness was exacerbated by fifth column activities within its major units and higher headquarters. Revolts of Croat soldiers broke out in all three divisions in the first few days, causing significant disruption to mobilisation and deployment. The town of Bjelovar was taken over by rebel troops. Widespread desertions of Croat troops, many of whom turned on their Serb comrades, made control even more difficult. German activity in the 4th Army sector in the first four days included limited objective attacks to seize crossings over the Mura and Drava rivers, along with air attacks by the Luftwaffe.

The formation and expansion of German bridgeheads were facilitated by fifth column elements of the Croatian nationalist Ustaše organisation and their sympathisers among the Croat-majority populace of the 4th Army sector. Elements of the 4th Army did put up scattered resistance to the Germans, but it began to withdraw southwards on 9 April, and on 10 April it quickly ceased to exist as an operational formation in the face of two determined armoured thrusts by XLVI Motorised Corps from bridgeheads at Gyékényes and Barcs. The 14th Panzer Division captured Zagreb late that day, and the Germans facilitated the proclamation of an independent Croatian state. A senior staff officer at the headquarters of the 1st Army Group who sympathised with the Ustaše issued orders redirecting formations and units of the 4th Army away from the advancing Germans, and fifth column elements even arrested some 4th Army headquarters staff.

Under the leadership of its commander, Armijski đeneral[lower-alpha 2] Petar Nedeljković, the mostly ethnic Serb remnants of the 4th Army attempted to establish defensive positions in northeastern Bosnia, but were brushed aside by the 14th Panzer Division as it drove east towards Sarajevo, which fell on 15 April. A ceasefire was agreed on that day, and the remains of the 4th Army were ordered to stop fighting. The Yugoslav Supreme Command surrendered unconditionally effective on 18 April.

Background

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was created with the merger of Serbia, Montenegro and the South Slav-inhabited areas of Austria-Hungary on 1 December 1918, in the immediate aftermath of World War I. The Army of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was established at war's end to defend the new state. It was formed around the nucleus of the victorious Royal Serbian Army, as well as armed formations raised in regions formerly controlled by Austria-Hungary. Many former Austro-Hungarian officers and soldiers became members of the new army.[2] From the beginning, much like other aspects of public life in the new kingdom, the army was dominated by ethnic Serbs, who saw it as a means by which to secure Serb political hegemony.[3]

The army's development was hampered by the kingdom's poor economy, and this continued through the 1920s. In 1929, King Alexander changed the name of the country to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, at which time the army was renamed the Royal Yugoslav Army (Serbo-Croatian: Vojska Kraljevine Jugoslavije, VKJ). The army budget remained tight, and as tensions rose across Europe during the 1930s, it became difficult to secure weapons and munitions from other countries.[4] Consequently, at the time World War II broke out in September 1939, the VKJ had several serious weaknesses, which included reliance on draught animals for transport, and the large size of its formations. Infantry divisions had a wartime strength of 26,000–27,000 men,[5] as compared to contemporary British infantry divisions of half that strength.[6] These characteristics resulted in slow, unwieldy formations, and the inadequate supply of arms and munitions meant that even the very large Yugoslav formations had low firepower.[7] Older generals better suited to the trench warfare of World War I were combined with an army that was not equipped or trained to resist the fast-moving combined arms approach used by the Germans in Poland and France.[8][9]

The weaknesses of the VKJ in strategy, structure, equipment, mobility and supply were exacerbated to a significant degree by serious ethnic disunity within Yugoslavia that had resulted from two decades of Serb hegemony and the attendant lack of political legitimacy achieved by the central government.[10][11] Attempts to address such disunity came too late to ensure that the VKJ was a cohesive force. Fifth column activity was also a serious concern, not only from the Croatian nationalist Ustaše but also from the country's Slovene and ethnic German minorities.[10]

Formation and composition

Peacetime organisation

Yugoslav war plans saw the 4th Army organised and mobilised on a geographic basis from the peacetime 4th Army District, which was divided into three divisional districts, each of which was subdivided into regimental regions.[12] Zagreb, Dugo Selo and Sisak were key centres for the mobilisation and concentration of the 4th Army due to their good rail infrastructure.[13] Prior to the issue of mobilisation orders for the 4th Army, the 4th Army District headquarters had been involved in planning border defences and conducting exercises for border troops, including demolition plans for bridges and other infrastructure in the event of war.[14]

On 8 June 1940, the Yugoslav Supreme Command had issued orders to the 4th Army District headquarters to make all necessary preparations for defence and demolitions and ordered a 14-day exercise for border troops. 4th Army District headquarters submitted a progress report on this work on 30 January 1941. This report indicated that along the Hungarian border, bunkers and trenches had been constructed for the immediate defence of the Drava along the Yugoslav-Hungarian border, in particular at Varaždin, Koprivnica, Virovitica and Slatina, but no obstacles such as barbed wire entanglements or anti-tank ditches had been developed.[14]

Wartime organisation

The 4th Army was commanded by Armijski đeneral[lower-alpha 3] Petar Nedeljković, and his chief of staff was Brigadni đeneral[lower-alpha 4] Anton Lokar.[15] The 4th Army consisted of:[15]

- 27th Infantry Division Savska

- 40th Infantry Division Slavonska

- 42nd Infantry Division Murska

- Detachment Ormozki (brigade-strength)

- 127th Infantry Regiment

- 81st Cavalry Regiment

Army-level support was provided by the motorised 1st Heavy Artillery Regiment, the 81st Army Artillery Regiment, the motorised 4th Anti-Aircraft Battalion, six border guard battalions and the motorised 4th Army Anti-Aircraft Company. The 4th Air Reconnaissance Group comprising eighteen Breguet 19s was attached from the Royal Yugoslav Air Force (Serbo-Croatian: Vazduhoplovstvo Vojske Kraljevine Jugoslavije, VVKJ) and was based at Pleso airfield near Velika Gorica just south of Zagreb.[15][16] The troops of the 4th Army included a high percentage of Croats.[17]

Deployment plan

_location_map.svg.png)

The 4th Army was part of the 1st Army Group, which was responsible for the defence of northwestern Yugoslavia, with the 4th Army defending the eastern sector along the Hungarian border, and the 7th Army along the Reich and Italian borders. The 1st Cavalry Division was to be held as the 1st Army Group reserve around Zagreb. On the left of the 4th Army, the boundary with the 7th Army ran from Gornja Radgona on the Mura through Krapina and Karlovac to Otočac. On the right of the 4th Army was the 2nd Army of the 2nd Army Group, with the boundary running from just east of Slatina through Požega towards Banja Luka. The Yugoslav defence plan saw the 4th Army deployed in a cordon behind the Drava between Varaždin and Slatina.[18] The planned deployment of the 4th Army from west to east was:[19]

- Detachment Ormozki, responsible for the border between Gornja Radgona and the triple border with the Reich and Hungary, but with its main defences along the Drava between the confluence with the Dravinja and Petrijanec and its headquarters in Klenovnik;

- 42nd Infantry Division Murska, opposite the Hungarian city of Nagykanizsa, between the triple border with the Reich and Hungary and the confluence of the Mura at Legrad, with divisional headquarters at Seketin, just south of Varaždin;[20]

- 27th Infantry Division Savska, opposite the Hungarian village of Gyékényes, between the confluence of the Mura at Legrad and Kloštar Podravski, with divisional headquarters at Kapela, north of Bjelovar; and[21]

- 40th Infantry Division Slavonska opposite the Hungarian town of Barcs, between Kloštar Podravski and Čađavica, with the main line of defence along the northern slopes of the Bilogora mountain range, and divisional headquarters at Pivnica Slavonska.[22]

Border guard units in the 4th Army area of responsibility consisted of:[23]

- the 601st Independent Battalion in the sector of the Detachment Ormozki,

- the 341st Reserve Regiment in the sector of the 42nd Infantry Division Murska,

- the 3rd Battalion of the 393rd Reserve Regiment and 576th Independent Battalion in the sector of the 27th Infantry Division Savska, and

- the 2nd Battalion of the 393rd Reserve Regiment in the sector of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska.

Mobilisation

After unrelenting pressure from Adolf Hitler, Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941. On 27 March, a military coup d'état overthrew the government that had signed the pact, and a new government was formed under the VVKJ commander, Armijski đeneral Dušan Simović.[24] A general mobilisation was not called by the new government until 3 April 1941, out of fear of offending Hitler and thus precipitating war.[25] However, on the same day as the coup Hitler issued Führer Directive 25 which called for Yugoslavia to be treated as a hostile state, and on 3 April, Führer Directive 26 was issued, detailing the plan of attack and command structure for the invasion.[26]

According to a post-war U.S. Army study, by the time the invasion commenced, the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska was partly mobilised, and the remaining two divisions had only commenced mobilisation.[27] The Yugoslav historian Velimir Terzić describes the mobilisation of the 4th Army as a whole on 6 April as "only partial",[28] and states the headquarters of the 4th Army was mobilising northeast of Dugo Selo, 20 kilometres (12 mi) east of Zagreb, with 30–35 percent of the staff officers and 10 percent of the soldiers having reported for duty.[22]

Detachment Ormozki

Detachment Ormozki was an adhoc formation based on the headquarters of the 1st Cavalry Brigade, with an infantry regiment attached from the 32nd Infantry Division Triglavski, and two cavalry regiments and a squadron of cavalry artillery attached from the 1st Cavalry Division. On 6 April, it was concentrating in the Ormož area, as follows:[29]

- the detachment commander and his headquarters staff were in Čakovec;

- the 39th Infantry Regiment was marching from Celje via Lepoglava to Varaždin, but on 6 April had only reached Rogatec;

- the 6th Cavalry Regiment was mobilising in Zagreb;

- the 8th Cavalry Regiment was mobilising in Čakovec;

- a squadron of cavalry artillery was moving from Varaždin to the concentration area, and had reached Vratno; and

- the 1st Bicycle Battalion had departed Ljubljana, and on 5 April had reached Žalec.

The 39th Infantry Regiment was subsequently transferred to the 42nd Infantry Division Murska, leaving Detachment Ormozki predominantly as a cavalry formation.[20]

42nd Infantry Division Murska

The 42nd Infantry Division Murska had only commenced mobilisation, and was largely in its mobilisation centres or moving to concentration areas. On 6 April, the elements of the division were located as follows:[20]

- the divisional commander Divizijski đeneral[lower-alpha 5] Borisav Ristić and his headquarters staff were mobilising in the Zagreb area

- the 36th Infantry Regiment was concentrating in the Ludbreg district

- the 105th Infantry Regiment, with about 55 percent of its troops, was concentrating in the Varaždin area

- the 126th Infantry Regiment was mobilising in Zagreb

- the 42nd Artillery Regiment headquarters and two batteries were mobilising in Zagreb, with the remaining two batteries mobilising in Varaždin

- the divisional cavalry squadron was located in Čakovec

- the remainder of the divisional units were mobilising in Zagreb

Orders were subsequently issued for the 36th Infantry Regiment to join the 27th Infantry Division Savska, replaced by the 39th Infantry Regiment from Detachment Ormozki. Two artillery batteries from the 40th Artillery Regiment of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska that were mobilising in Varaždin were ordered to join the 42nd Infantry Division Murska.[20]

27th Infantry Division Savska

The 27th Infantry Division Savska had only commenced mobilisation, and was largely in its mobilisation centres or moving to concentration areas.[21] On 4 April, Nedeljković had reported that the division could not move for another 24 hours due to lack of vehicles.[30] A small proportion of the division was in its planned positions on 6 April:[21]

- the divisional commander Divizijski đeneral August Marić and his headquarters staff were mobilising in Zagreb

- the 35th Infantry Regiment (less its 3rd Battalion) was marching from Zagreb to Križevci, with its 3rd Battalion still in Zagreb

- the 53rd Infantry Regiment, with about 50 percent of its troops and 15 percent of its animals, was moving by rail from its mobilisation centre in Karlovac via Križevci to Koprivnica, with its 1st Battalion detraining in Koprivnica

- the 104th Infantry Regiment was marching from its mobilisation centre in Sesvete via Dugo Selo to Bjelovar

- Two batteries of the 27th Artillery Regiment were in position in Novigrad Podravski and near Koprivnica, with the rest of the 27th Artillery Regiment still mobilising in Zagreb and Varaždin

- the divisional cavalry squadron was mobilising in Čakovec but had no horses, and the divisional machine gun battalion was mobilising in Zagreb but had no animal transport

- the remainder of the divisional units were at their mobilisation centres in and around Zagreb

40th Infantry Division Slavonska

The 40th Infantry Division Slavonska was partially mobilised, with some elements of the division still mobilising, some in concentration areas, and only a small proportion actually deployed in their planned positions:[22]

- the divisional commander Brigadni đeneral Ratko Raketić and his headquarters staff were mobilising in Bjelovar

- the 42nd Infantry Regiment with two battalions was marching towards their positions near Daruvar, while the rest of the regiment was mobilising in Bjelovar and could not move due to lack of draught animals

- the 43rd Infantry Regiment, with about 75–80 percent of its troops and 30 percent of its animals, was marching from its mobilisation centre in Požega towards Našice, but had only reached Jakšić, 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) northeast of Požega

- the 108th Infantry Regiment was marching from Bjelovar but had only reached Severin

- the 40th Artillery Regiment was still mobilising with the headquarters and one battery in Osijek and two batteries in Varaždin

- the divisional cavalry squadron and machine gun battalion were unable to deploy from Virovitica due to lack of animals, although on 5 April, Nedeljković had requisitioned private cars for the machine gun battalion and ordered it to concentrate at Lukač northeast of Virovitica

- the remainder of the divisional units were at their mobilisation centres in and around Bjelovar

The 43rd Infantry Regiment was ordered to march east to join the 17th Infantry Division Vrbaska, which was part of the 2nd Army Group's 2nd Army. The 89th Infantry Regiment, originally allocated to the 17th Infantry Division Vrbaska, was ordered to march from its mobilisation location in Sisak and join the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska to replace the 43rd Infantry Regiment. The divisional cavalry did not receive sufficient horses, and had to deploy on foot as infantry. The division was without artillery support throughout the fighting because the 40th Artillery Regiment did not complete mobilisation.[31]

Army-level support

Army-level support units were mobilising as follows:[32]

- the 81st Heavy Artillery Regiment was mobilising in Zagreb, but there were only sufficient strong draught animals to pull the guns of two of the four batteries. These two batteries were moving towards the border, but en route they were weakened by desertion

- the 81st Cavalry Regiment was mobilised with personnel from the Cazin district of northwest Bosnia, but due to sabotage by the Croatian fascist organisation, the Ustaše, no horses had been mobilised from the Zagreb military district

- the 4th Army anti-aircraft units were deployed at Lipik

- supply units were poorly mobilised due to lack of vehicles and draught animals

Overall condition of the 4th Army

At the time of the invasion, many units of the 4th Army were still at their mobilisation centres or in their concentration areas, and only a small number of units had actually deployed into their planned positions to defend the border. A significant number of conscripts did not report to their mobilisation centres. The logistics of the 4th Army were in a poor state, mainly due to a lack of livestock and vehicles for transport, but also due to fifth column sabotage by the Ustaše and their sympathisers, to the extent that many units did not even have 10 per cent of their transport needs. It was also equipped poorly, lacking in many tools of modern warfare, including tanks, light artillery, anti-aircraft weapons and air support. These deficiencies affected both its fighting power and morale.[33]

Operations

6 April

German Army headquarters wanted to capture the bridges over the Drava intact, and from 1 April had issued orders to the 2nd Army to conduct preliminary operations aimed at seizing the bridges at Barcs and Gyékényes by coup de main. As a result, limited objective attacks were launched along the line of the Drava by the XLVI Motorised Corps, despite the fact that they were not expected to launch offensive operations until 10 April.[34] Similar operations occurred on the extreme left flank of the 4th Army, where raiding parties and patrols from LI Infantry Corps seized high ground on the south side of the Drava.[35]

In the early hours of 6 April 1941, units of the 4th Army were located at their mobilisation centres or were marching toward the Hungarian border.[36] LI Infantry Corps seized the intact bridge over the Mura at Gornja Radgona.[35] About 05:20, the Yugoslav 601st Independent Battalion on the border in the Prekmurje region forward of Detachment Ormozki was attacked by German troops advancing across the Reich border, and began withdrawing south into the Međimurje region. About 06:20, Germans troops also crossed the Hungarian border and attacked border troops at Dolnja Lendava. Shortly after this, further attacks were made along the Drava between Ždala and Gotalovo in the area of the 27th Infantry Division Savska with the intention of securing crossings over the river, but they were unsuccessful. The Germans cleared most of Prekmurje up to Murska Sobota and Ljutomer during the day.[37]

A bicycle-mounted detachment of the 183rd Infantry Division captured Murska Sobota without encountering resistance.[35] During the day, the German Luftwaffe bombed and strafed Yugoslav positions and troops on the march. By the afternoon, German troops had captured Dolnja Lendava,[37] and by the evening it had become clear to the Germans that the Yugoslavs would not be resisting stubbornly at the border. XLVI Motorised Corps was then ordered to begin seizing bridges over the Mura at Mursko Središće and Letinja, and over the Drava at Gyékényes and Barcs. The local attacks were sufficient to inflame dissent within the largely Croat 4th Army, who refused to resist Germans they considered their liberators from Serbian oppression during the interwar period.[38] In the afternoon, German Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers of Sturzkampfgeschwader 77 escorted by Messerschmitt Bf 109E fighters caught the Breguet 19s of the 4th Air Reconnaissance Group on the ground at Velika Gorica, destroying most of them.[39]

The continuing mobilisation and concentration of the 4th Army was hampered by escalating fifth column activities and propaganda fomented by the Ustaše. Some units stopped mobilising, or began returning to their mobilisation centres from their concentration areas. During the day, Yugoslav sabotage units attempted to destroy bridges over the Mura at Letinja, Mursko Središće and Kotoriba, and over the Drava at Gyékényes. These attempts were only partially successful, due to the influence of Ustaše propaganda and the countermanding of the demolition orders by the chief of staff of the 27th Infantry Division Savska, Major Anton Marković.[37] The Yugoslav radio network in the 4th Army area was sabotaged by the Ustaše on 6 April, and radio communications within the 4th Army remained poor throughout the fighting.[40]

7 April

Mura bridgeheads

Reconnaissance units of the XLVI Motorised Corps crossed the Mura at Letenye and Mursko Središće early on 7 April, and captured Čakovec.[41] Ustaše propaganda led the bulk of two regiments from the 42nd Infantry Division Murska to revolt; only two battalions from the units deployed to their allocated positions.[36] In the face of the German advance, the border troops of the 601st Independent Battalion and 341st Reserve Regiment withdrew towards the Drava.[42]

Gyékényes bridgehead

About 05:00 on 7 April, two to three battalions of the XLVI Motorised Corps commenced crossing the Drava at Gyékényes,[41] and attacked towards Koprivnica.[36] In response to the German crossing at Gyékényes, the 53rd Infantry Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division Savska withdrew towards Koprivnica and took up defensive positions in a series of villages including Torčec. In order to stop this German penetration and gain more time for the concentration of the 27th Infantry Division Savska, elements of the 27th Artillery Regiment were sent to support the defensive line near Torčec, which was placed under the command of the division's commanding officer for infantry.[41] About 07:30, the commander of the Yugoslav 1st Army Group, Armijski đeneral Milorad Petrović met with Nedeljković at Zagreb and ordered him to go to Koprivnica and prepare a counterattack against the bridgehead, to commence at 15:00. The counterattack plan was unable to be carried out, as the necessary units could not reach their positions.[41]

About 10:30, the Germans reached the defensive line near Torčec, and fighting began.[41] The few remaining Breguet 19s of the 4th Air Reconnaissance Group mounted attacks on the bridge over the Drava at Gyékényes.[43] After the Germans reinforced their bridgehead with two more battalions, they overcame the Yugoslav defenders, who had suffered significant losses and were running low on artillery ammunition. About 18:00, the 53rd Infantry Regiment withdrew to Koprivnica with its artillery support, and it remained in the town during the night.[44] At 23:00, following orders from Petrović that he was to attack on 8 April at all costs, Nedeljković issued orders for a counterattack to be carried out early on 8 April.[42]

Barcs bridgehead

About 19:00 on 7 April, German units in regimental strength with a few tanks began to cross the Drava near Barcs in the sector of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska. They quickly overcame the resistance of the 2nd Battalion of the 393rd Reserve Regiment, who were affected by Ustaše propaganda. The Yugoslavs abandoned their positions and weapons and retreated to Virovitica.[42] The 108th Infantry Regiment of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska had mobilised in Bjelovar and on 7 April was marching towards Virovitica to take up positions. That night, Croat members of that regiment revolted, arresting their Serb officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers. The regiment then marched back to Bjelovar, where it joined up with other rebellious units about noon on 8 April.[36]

As the 108th Infantry Regiment was responsible for the right sector of the divisional defence, this meant that the 42nd Infantry Regiment, which was originally responsible only for the left sector, had to extend across the entire divisional frontage.[21] During the night, the commander of the divisional cavalry squadron sent patrols towards the German bridgehead, but local Ustaše sympathisers misled them into believing the Germans were already across the Drava at Barcs in strength.[42] The Germans were subsequently able to consolidate their bridgehead at Barcs overnight.[36]

Overall situation

By late evening on 7 April, Petrović's reports to Supreme Headquarters noted that the 4th Army was exhausted and its morale had been degraded significantly, and that Nedeljković concurred with his commander's assessment. During the day, Nedeljković moved his headquarters from Zagreb to Bjelovar.[42]

8 April

On 8 April, the German XLVI Motorised Corps continued with its limited objective attacks to expand their bridgeheads at Barcs and Gyékényes, capturing Kotoriba, a village upstream from Legrad. A German regiment broke through the border troops in the sector of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska, and approached Virovitica. At this point, the entire divisional sector was defended by the divisional cavalry squadron which had been transported there in requisitioned cars due to the lack of horses. Two understrength and wavering battalions of the 42nd Infantry Regiment arrived at Pčelić, 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) southwest of Virovitica.[45]

Mura bridgeheads

In the areas of the 42nd Infantry Division Murska and Detachment Ormozki, the Germans cleared the territory north of the Drava, and border guard units were withdrawn south of the river. On this day, the 39th Infantry Regiment was transferred to the 42nd Infantry Division Murska from the Detachment Ormozki, and the 36th Infantry Regiment of the former joined the 27th Infantry Division Savska.[46]

Fall of Bjelovar

By noon, the rebels of the 108th Infantry Regiment were approaching Bjelovar, where they were joined by elements of the 42nd Infantry Regiment and other units of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska. The leader of the rebels in Bjelovar was Kapetan[lower-alpha 6] Ivan Mrak, a reserve aviator. When Nedeljković became aware of the rebels approach, he ordered the local gendarmerie commander to maintain order, but was advised this would not be possible, as local conscripts would not report for duty.[45] Headquarters of the 4th Army reported the presence of the rebels to Headquarters 1st Army Group, and it was suggested that the VVKJ could bomb the rebel units.[47] The 8th Bomber Regiment at Rovine was even warned to receive orders to use its Bristol Blenheim Mk I light bombers to bomb the 108th Infantry Regiment, but the idea was subsequently abandoned.[48] Instead, it was decided to request that the leader of the Croatian Peasant Party, Vladko Maček intervene with the rebels.[47]

Josip Broz Tito and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, then located in Zagreb, along with the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia, sent a delegation to 4th Army headquarters urging them to issue arms to workers to help defend Zagreb. Pavle Gregorić, who was a member of both Central Committees, went to the headquarters twice, and was able to speak briefly with Nedeljković, but could not convince him to do so. On the same day, Maček, who had returned to Zagreb after briefly joining Simović's post-coup government, agreed to send an emissary to the 108th Infantry Regiment of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska urging them to obey their officers, but they did not respond to his appeal.[49]

Later in the day, two trucks of rebels arrived at 4th Army headquarters in Bjelovar with the intention of killing the staff. The headquarters guard force prevented this, but the operations staff immediately withdrew from Bjelovar to Popovača.[47] After the rebels issued several unanswered ultimatums, around 8,000 rebels attacked Bjelovar, assisted by fifth-columnists within the city. The city then surrendered, and many Yugoslav officers and soldiers were captured by the rebels. When Nedeljković heard of the fall of the city, he called the Mayor of Bjelovar, Julije Makanec and threatened to bomb the city if the prisoners were not immediately released. Detained officers from 4th Army headquarters and the 108th Infantry Regiment were then sent to Zagreb. About 16:00, Nedeljković informed the Ban of Croatia, Ivan Šubašić of the revolt, but Šubašić was powerless to influence events. About 18:00, Makanec proclaimed that Bjelovar was part of an independent Croatian state.[46]

Gyékényes bridgehead

.jpg)

On the morning of 8 April, the 27th Infantry Division Savska was deployed around Koprivnica. The 104th Infantry Regiment supported by elements of the 27th Artillery Regiment was deployed northeast of the town behind the Drava between Molve and Hlebine. The 2nd Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division, which had been riding from its mobilisation centre in Virovitica to Zagreb, was allocated to the 27th Infantry Division Savska to assist with establishing its forward defences, and was deployed with two artillery batteries between the outskirts of Koprivnica and Bregi. The 53rd Infantry Regiment, and the remnants of the 2nd Battalion of the 36th Infantry Regiment and the 1st Battalion of the 35th Infantry Regiment (totalling around 500 men), and the 1st Battery of the 27th Artillery Regiment were located in the town itself. The 2nd Battalion of the 36th Infantry Regiment had not yet arrived in Koprivnica, and the divisional cavalry squadron had reached as far as Ivanec. The majority of the 81st Cavalry Regiment, which were army-level troops, were on the road from Zagreb to Koprivnica, although its 1st Squadron, which had been transported to Koprivnica in cars on 7 April, was deployed as part of an outpost line forward of Koprivnica supporting the 1st Battalion of the 53rd Infantry Regiment. The divisional headquarters was located 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) southwest of Koprivnica at Reka.[46]

In accordance with Nedeljković's orders, Marić's 27th Infantry Division Savska was to undertake a counterattack against the Gyékényes bridgehead on 8 April. Supported by two batteries of Skoda 75 mm Model 1928 mountain guns of the 27th Artillery Regiment, the attack consisted of three columns converging on the bridgehead. The right column, attacking from the area of Bregi, was to consist of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment supported by the divisional machine gun company. The centre column, consisting of the 53rd Infantry Regiment and the remnants of the 2nd Battalion of the 36th Infantry Regiment and the 1st Battalion of the 35th Infantry Regiment, directly supported by the 1st Battery of the 27th Artillery Regiment, would attack from Koprivnica. The left column, attacking from the vicinity of Herešin, was to consist of the dismounted 81st Cavalry Regiment.[46] As promised support from the 36th Infantry Regiment, 81st Cavalry Regiment and army-level artillery had not materialised, Marić postponed the counterattack to 16:00. When it was eventually launched, only the 2nd Cavalry Regiment and the 1st Squadron of the 81st Cavalry Regiment remained in contact with the Germans, south of Peteranec, and the 2nd Cavalry Regiment held that area throughout the night of 8/9 April, despite heavy German artillery fire. Of the other units involved in the counterattack, most were only at 25 percent of their full strength due to Ustaše-influenced desertions sparked by the rebellion within the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska. Two battalions of the 36th Infantry Regiment deserted during 8 April.[50]

Overall situation

By the evening of 8 April, the Yugoslav Supreme Headquarters was under the mistaken impression that the situation in the 4th Army's area of operation was relatively good, believing the penetration of German troops had been temporarily halted.[50] However, the effect of the rebellions and desertions within the 4th Army was significant within the flanking 2nd and 7th Armies, and contributed to further withdrawals. This was particularly marked in the area of the 7th Army, which was forced to withdraw from the Drava on the night of 8/9 April due to the situation in the 4th Army on its right flank, leading to the loss of Maribor.[51]

9 April

Mura bridgeheads

The Mura sector was quiet on 9 April. The 42nd Infantry Division Murska took the 39th Infantry Regiment under command, but the 105th Infantry Regiment and 341st Reserve Regiment began to disintegrate due to desertions. Due to the situation on the right flank of the 42nd Infantry Division Murska, 4th Army headquarters ordered it and Detachment Ormozki to withdraw from the Drava to behind the Bednja to conform to the line being held by the 27th Infantry Division Savska on its immediate right flank.[52]

Gyékényes bridgehead

On 9 April, the German XLVI Motorised Corps completed its preparations for full-scale offensive action by expanding its bridgehead at Gyékényes.[53] The cavalry units continued to fight the Germans around Peteranec, but the left sector of the divisional front line began to disintegrate. The commander of the right sector, Pukovnik[lower-alpha 7] Mihailo Georgijević ordered his troops to hold their positions and went to divisional headquarters to ask approval to discharge the Croats in his units. Marić would not inform 4th Army headquarters of this idea, so Georgijević went to Zagreb to speak to Petrović, and to further urge him to withdraw all troops that still wanted to fight to a line south of the Sava. According to Georgijević, Petrović ordered him to tell Marić to consider disarming his Croat troops, and to continue to hold positions on the line of the Bilogora, but to conduct a fighting withdrawal towards Zagreb and Sisak if the German pressure was too great. The intent of these orders was not implemented, as fifth column elements changed the wording so that orders were issued to discharge Croat troops and to retreat towards Zagreb without fighting.[54]

About 09:00, Marić and Marković went to Zagreb to see Petrović, who ordered them to immediately return to their division and continue to resist the Germans. On the return journey, they encountered most of their division withdrawing towards Križevci, with the exception of the cavalry units still fighting north of Koprivnica. Marić halted the retreat, and established positions around Mali Grabičani, making his headquarters at Križevci.[54] Georgijević dismissed his Croat troops and retreated with the rest of his force towards Zagreb, and the commander of the 104th Infantry Regiment discharged all his troops. In the afternoon, the hard-pressed cavalry units began to withdraw. About 14:00, the 2nd Cavalry Regiment withdrew to Novigrad Podravski via Bregi, but receiving a hostile reception from the Croat population, continued towards Bjelovar. About 18:00, the 1st Squadron of the 81st Cavalry Regiment withdrew via Koprivnica, reaching the rest of the division about 23:00. About 19:00, the Germans occupied Koprivnica without resistance. By evening, Marić's division numbered about 2,000 troops, the 36th Infantry Regiment and 81st Cavalry Regiment were widely dispersed, the 53rd Infantry Regiment had effectively ceased to exist, and his artillery regiment had only two horses to pull guns.[52]

The rebels in Bjelovar used the telegraph station and telephone exchange in the town to issue false orders to parts of the 104th Infantry Regiment directing them to withdraw from their positions. The rebels also contacted the Germans by telephone and sent representatives to meet the Germans at the Drava bridgeheads, to advise them that the roads had been cleared of obstacles, and Makanec invited them to enter Bjelovar. Nedeljković's threats to bomb the town did not materialise, and rebels and deserters began to converge on Bjelovar, bringing with them many Serb officers and soldiers who soon filled the town's jails.[53]

Barcs bridgehead

On the morning of 9 April, the German bridgehead at Barcs had expanded to Lukač, 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) north of Virovitica.[55] Following up the withdrawal of the divisional cavalry squadron, the Germans seized Suho Polje, west of Virovitica, cutting the main road to Slatina,[55] and the rebel Croat troops at Bjelovar made contact with them.[36] By 11:00, the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska front line consisted of the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 42nd Infantry Regiment and a troop of the divisional cavalry squadron on the right, and the 4th Battalion of the 42nd Infantry Regiment and a troop of the divisional cavalry on the left. The 3rd Battalion of the 42nd Infantry Regiment was held in depth. The left flank was screened by the rest of the divisional cavalry squadron deployed around Pitomača.[55] The 89th Infantry Regiment, marching from its concentration area in Sisak, arrived at divisional headquarters at Pivnica Slavonska,[55] to replace the 43rd Infantry Regiment, which had been transferred to the 17th Infantry Division Vrbaska.[21]

Other reinforcements included elements of the 4th Army anti-aircraft units sent from Lipik, but the divisional artillery regiment had not completed mobilisation.[55] The rebels in Bjelovar issued false orders to the 1st Battalion of the 42nd Infantry Regiment, directing it to fall back to Bjelovar.[53] At 11:15, Nedeljković arrived at divisional headquarters and shortly afterwards ordered Raketić to launch a counterattack on the German bridgehead at Barcs at dawn the following day. Nedeljković also visited Divizijski đeneral Dragoslav Milosavljević, the commander of the 17th Infantry Division Vrbaska on the right flank of the 4th Army, to arrange support from that division during the pending attack.[55] However, because the majority of that division's troops had yet to arrive from Bosnia, all it was able to do was advance its left flank, stationing battalions in Čačinci and Crnac west of Slatina.[54] The 40th Infantry Division Slavonska spent the remainder of the day preparing for the counterattack, but were hindered by German artillery and air attacks. In an indication of the state of his division, during a visit to the front line, Raketić and his chief of staff were fired at by troops of the 42nd Infantry Regiment.[55]

Overall situation

Elements of the 4th Army began to withdraw southwards on 9 April.[56] On the night of 9/10 April, those Croats that had remained with their units also began to desert or turn on their commanders,[57] and in the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska, almost all the remaining troops were Serbs.[55] Due to the increasing momentum of the revolt, Petrović concluded that the 4th Army was no longer an effective formation and could not resist the Germans.[53] Maček issued a further ineffectual plea to calm the rebellion.[52] On the evening of 9 April, Generaloberst Maximilian von Weichs, commander of the German 2nd Army, was ready to launch major offensive operations from the bridgeheads on the following day.[58] His plan involved two main thrusts. The first would be spearheaded by the 14th Panzer Division breaking out of the Gyékényes bridgehead and drive towards Zagreb,[59] and the second would see the 8th Panzer Division break out of the Barcs bridgehead and turn east between the Drava and Sava to attack towards Belgrade.[17]

10 April

Early on 10 April, Pukovnik Franjo Nikolić, the head of the operations staff with the headquarters of the 1st Army Group,[60] left his post and visited the senior Ustaše leader Slavko Kvaternik in Zagreb. He then returned to headquarters and redirected 4th Army units around Zagreb to either cease operations or to deploy to innocuous positions. These actions reduced or eliminated armed resistance to the German advance.[61]

Fall of Varaždin

About 09:45, the LI Infantry Corps began crossing the Drava, but construction of a bridge near Maribor was suspended because the river was in flood. Despite this, the 183rd Infantry Division managed to secure an alternative crossing point, and established a bridgehead.[58] This crossing point was a partially destroyed bridge, guarded by a single platoon of the 1st Bicycle Battalion of Detachment Ormozki. This crossing, combined with the withdrawal of the 7th Army's 38th Infantry Division Dravska from the line Slovenska Bistrica–Ptuj exposed the left flank of Detachment Ormozki. The Detachment attempted to withdraw south, but began to disintegrate during the night 10/11 April, and the 1st Bicycle Battalion left to return to Ljubljana. In the afternoon, the remaining elements of the 42nd Infantry Division Murska also began to withdraw though Varaždinske Toplice to Novi Marof, leaving the Ustaše to take control of Varaždin.[62]

Gyékényes bridgehead

On the same day, the 14th Panzer Division, supported by dive bombers, crossed the Drava and drove southwest towards Zagreb on snow-covered roads in extremely cold conditions. Initial air reconnaissance indicated large concentrations of Yugoslav troops on the divisional axis of advance, but these troops proved to be withdrawing towards Zagreb.[59] Degraded by revolt and fifth-column activity, the 27th Infantry Division Savska numbered about 2,000 effectives when the German attack began. The 14th Panzer Division vanguard reached their positions in the Bilogora range around 08:00, and the remnants of the division began withdrawing towards Križevci under heavy air attack. When they reached the town around 14:00, they were quickly encircled by German motorised troops that had outflanked them. The divisional headquarters staff escaped, but were captured a little further down the road at Bojnikovec. The remnants of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment had to fight its way towards Bjelovar, but was attacked by German tanks on the outskirts, captured and detained.[63] The 14th Panzer Division continued its almost completely unopposed drive on Zagreb using two routes, Križevci – Dugo Selo – Zagreb and Bjelovar – Čazma – Ivanić-Grad – Zagreb.[64]

Fall of Zagreb

About 17:45 on 10 April, Kvaternik and SS-Standartenführer[lower-alpha 8] Edmund Veesenmayer went to the radio station in Zagreb and Kvaternik proclaimed the creation of the Independent State of Croatia (Croatian: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH).[66] The 35th Infantry Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division Savska was disbanded by its commander when he heard news of the proclamation.[21] By 19:30 on 10 April, lead elements of the 14th Panzer Division had reached the outskirts of Zagreb, having covered nearly 160 kilometres (99 miles) in a single day.[59] By the time it entered Zagreb, the 14th Panzer Division was met by cheering crowds, and had captured 15,000 Yugoslav troops, including 22 generals.[67]

About 19:45, the 1st Army Group held a conference in Zagreb, just as German tanks were entering the city. Nedeljković told Petrović that he could no longer hold his positions, but despite this, Petrović ordered him to hold for at least 2–3 days to enable the withdrawal of the 7th Army to the Kupa river. Nedeljković replied that he no longer had an army, and suggested that all Serb officers and men be ordered back to form a defensive line along the Sava and Una rivers. Petrović refused to consider this, but ordered the 1st Cavalry Division to form a defensive line along the Sava between Jasenovac and Zagreb.[68]

Barcs bridgehead

The 40th Infantry Division Slavonska was battered by German artillery fire during the night 9/10 April. Seriously depleted by desertion and weakened by revolt, it was unable to mount the ordered counterattack against the Barcs bridgehead on the morning of 10 April. The 42nd Infantry Regiment could only muster 600 men, and the 86th Infantry Regiment slightly more. The divisional cavalry squadron was also heavily reduced in strength, and divisional artillery amounted to one anti-aircraft battery. The border units, responsible for demolition tasks on the line from Bjelovar south to Čazma, refused to follow orders. Having abandoned the counterattack, Raketić decided to establish a defensive line at Pćelić to hinder German movement east towards Slatina.[69]

Soon after dawn, the main thrust of the XLVI Motorised Corps, consisting of the 8th Panzer Division leading the 16th Motorised Infantry Division, crossed the Drava at Barcs.[17] Anti-tank fire destroyed a few of the lead tanks, but after the Germans reinforced their vanguard, the resistance of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska had been broken by noon. The remaining troops of the 42nd Infantry Regiment were either captured or fled into the hills to the south. Units of the 89th Infantry Regiment, which had been providing depth to the defensive position, began retreating south towards Slavonska Požega. Ustaše sympathisers and Yugoslav Volksdeutsche (ethnic German) troops either ran away or surrendered.[69] By 13:30, the hard-pressed divisional cavalry squadron began to withdraw south towards Daruvar, attacking rebelling troops along their route. Raketić himself fled to Nova Gradiška via Voćin and Slavonska Požega, during which his car was again fired on by rebel troops.[63] The 8th Panzer Division continued southeast between the Drava and Sava rivers, and meeting almost no further resistance, had reached Slatina by evening.[17] Right flank elements of the 8th Panzer Division penetrated south into the Bilogora range, reaching Daruvar and Voćin by evening.[69]

Overall situation

Late in the day, as the situation was becoming increasingly desperate throughout the country, Simović, who was both the Prime Minister and Yugoslav Chief of the General Staff, broadcast the following message:[17]

All troops must engage the enemy wherever encountered and with every means at their disposal. Don't wait for direct orders from above, but act on your own and be guided by your judgement, initiative, and conscience.

The XLVI Motorised Corps encountered little resistance from the 4th Army, particularly from the 27th Infantry Division Savska and 40th Infantry Division Slavonska, and by the evening of 10 April the whole 4th Army was disintegrating, and all aircraft of the 4th Air Reconnaissance Group had been destroyed. Petrović wanted to dismiss Marić as commander of the 27th Infantry Division Savska due to suspicions that he was an Ustaše sympathiser, but could not identify a suitable replacement.[70]

About 23:00, German 2nd Army headquarters directed the 14th Panzer Division to penetrate past Zagreb towards Karlovac to link up with the Italian 2nd Army, and also directed the 8th Panzer Division and 16th Motorised Infantry Division to drive to the north of Belgrade to link up with the First Panzer Group which was thrusting towards Belgrade from the east. At midnight, 2nd Army headquarters declared that the Yugoslav northern front had been decisively defeated, and tasked corps engineer units to consolidate bridging across major rivers, particularly over the Sava at Brežice west of Zagreb to facilitate the advance of the 14th Panzer Division towards Karlovac. The main body units of the XLVI Motorised Corps moved forward to Virovitica and Slatina, and 2nd Army headquarters moved forward to establish itself in Maribor, protected by the 538th Frontier Guard Division. At midnight, General der Panzertruppe Heinrich von Vietinghoff issued orders for the 8th Panzer Division to continue towards Belgrade via Osijek, but directed the 16th Motorised Infantry Division to thrust west as far as Sremska Mitrovica then turn south to drive towards Sarajevo via Zvornik.[70]

11 April

Held up by freezing weather and snow storms, LI Corps was approaching Zagreb from the north,[67] and broke through a hastily established defensive line between Pregrada and Krapina.[71] Bicycle-mounted troops of the 183rd Infantry Division turned east to secure Ustaše-controlled Varaždin. The German-installed NDH government called on all Croats to stop fighting, and in the evening, LI Infantry Corps entered Zagreb and relieved the 14th Panzer Division.[67]

On 11 April, Petrović and the staff of 1st Army Group headquarters were captured by Ustaše at Petrinja, and the rear area staff of 4th Army headquarters were captured by Ustaše at Topusko. The personnel of both headquarters were soon handed over to the Germans by their captors. Nedeljković and his operations staff escaped, and made their way to Prijedor.[72] Other units were retreating into Bosnia, including two battalions and 2–3 artillery batteries from the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska. Nedeljković attempted to deploy rear area units of the 17th Infantry Division Vrbaska into a defensive line along the Una at Bosanska Dubica, Bosanska Kostajnica, Bosanski Novi, Bosanska Krupa and Bihać, and called Sarajevo to request reinforcements. With his remaining troops, Raketić attempted to establish a defensive line along the Sava between Jasenovac and the mouth of the Vrbas. These efforts were significantly hampered by Ustaše propaganda.[73]

The 42nd Infantry Division Murska and Detachment Ormozki were cut off north of Zagreb, and those elements that did not disperse to their homes withdrew into the Ivanšćica and Kalnik mountains. Leaders of a Slovene nationalist movement announced that they no longer recognised the Yugoslav government, and began to call for Slovene soldiers to cease fighting and return home, compounding the effect of Ustaše propaganda on Croat military personnel and accelerating the disintegration of Yugoslav forces.[74]

Elements of the 14th Panzer Division thrust west from Zagreb into the rear of the withdrawing 7th Army and captured Karlovac on 11 April. [71] The break-up of the 4th Army and westward thrust of the 14th Panzer Division opened up the Bosnian interior to the Germans, and also threatened the left flank of the Yugoslav forces attempting to establish a defensive line along the Sava.[72] The German orders for the following day were to pursue the remnants of Yugoslav Army through Bosnia towards Sarajevo, where they would be met by the First Panzer Group attacking from the south and east.[71]

The 8th Panzer Division and 16th Motorised Infantry Division faced almost no resistance as they drove east towards Belgrade, capturing Našice, Osijek, Vinkovci and Vukovar during the day. On the night of 11/12 April, they captured Sremska Mitrovica, Ruma and secured a crossing over the Danube via an undamaged bridge near Bogojevo.[71]

12 April

On 12 April, Nedeljković received orders direct from Simović that he was to defend the Bosanska Krajina region by holding the Germans along the Sava and Una, using a new 4th Army formed from the remnants of the 4th and 7th Armies. However, by this time the 4th Army amounted to about 250–300 infantry and 12 artillery pieces, divided between Bosanska Kostajnica, Bosanski Novi, Bihać and Prijedor. In order to delay the German advance, he was ordered to destroy all the bridges on the Una before withdrawing to a line on the Vrbas.[75]

The 14th Panzer Division swiftly captured Vrbosko, linking up with the Italians as they attacked down the Adriatic coast, thereby cutting off the remaining elements of the 7th Army. It was then ordered to split into three columns to pursue the Yugoslavs across Bosnia. The northern column headed for Doboj, the central column for Sarajevo, and the southern column drove towards Mostar in Herzegovina.[75]

About 18:00, Nedeljković received a telephone call from Simović and reported that Bosanska Dubica, Bosanski Novi and Prijedor had all fallen, but that the bridges on the Sava and Una would be demolished later that night, and that he and his remaining staff would be leaving at 20:00 for Jajce. By this time, Serb officers and soldiers were also deserting in significant numbers.[75]

Fate

The following day, the northern column of the 14th Panzer Division drove via Glina and crossed the Una at both Bosanska Kostajnica and Bosanski Novi before continuing its push east. Elements of LI Infantry Corps also pushed east, establishing bridgeheads over the Kupa. A fragment of the 40th Infantry Division Slavonska, numbering around 300 troops, which had been holding a position on the Sava at Bosanska Gradiška, retreated to Jajce via Banja Luka. When they arrived at Jajce, Nedeljković ordered them to take up blocking positions on the narrow Vrbas valley at Krupa on the road between Banja Luka and Mrkonjić Grad. The rear area units of the 17th Infantry Division Vrbaska were ordered to block the road from Kotor Varoš to Doboj.[76]

In response to Nedeljković's request for reinforcements, Simović had sent a number of units by rail via Tuzla. These included a cadet battalion and a company of the 27th Infantry Regiment, detached from the 1st Infantry Division Cerska. By the time the reinforcements arrived, Banja Luka had been evacuated in the face of German tanks and an Ustaše-led revolt. The cadet battalion was redirected to Ključ to block the road Ključ – Mrkonjić Grad – Jajce. Nedeljković did not have the option of withdrawing via Bugojno or Prozor as those towns had been taken over by the Ustaše.[76]

On 14 April, under pressure from the 14th Panzer Division, remnants of the 4th Army continued to withdraw towards Sarajevo via Jajce and Travnik. The cadet battalion at Ključ managed to briefly delay the German advance through Mrkonjić Grad, but were overcome by tanks and air attacks. The bridge at Jajce was demolished at 23:15, and Nedeljković withdrew his headquarters to Travnik. The remaining units of the 4th Army continued to disintegrate.[77] The vanguard of the northern column of 14th Panzer Division surged forward to Teslić, with the central column only reaching Jajce.[78]

Early on 15 April, the northern column of the 14th Panzer Division closed on Doboj, and after overcoming resistance around that town, arrived in Sarajevo at 20:45. Before noon, Nedeljković received orders that a ceasefire had been agreed, and that all 4th Army troops were to remain in place and not fire on German personnel.[79] After a delay in locating appropriate signatories for the surrender document, the Yugoslav Supreme Command unconditionally surrendered in Belgrade effective at 12:00 on 18 April.[80] Yugoslavia was then occupied and dismembered by the Axis powers, with Germany, Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria and Albania all annexing parts of its territory.[81]

Notes

- ↑ The Royal Yugoslav Army did not field corps, but their armies consisted of several divisions, and were therefore corps-sized.

- ↑ Equivalent to a U.S. Army lieutenant general.[1]

- ↑ Equivalent to a U.S. Army lieutenant general.[1]

- ↑ Equivalent to a U.S. Army brigadier general.[1]

- ↑ Equivalent to a U.S. Army major general.[1]

- ↑ Equivalent to a U.S. Army captain.[1]

- ↑ Equivalent to a U.S. Army colonel.[1]

- ↑ Equivalent to a U.S. Army colonel.[65]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Niehorster 2013a.

- ↑ Figa 2004, p. 235.

- ↑ Hoptner 1963, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 60.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 58.

- ↑ Brayley & Chappell 2001, p. 17.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Hoptner 1963, p. 161.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 57.

- 1 2 Tomasevich 1975, p. 63.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 111.

- ↑ Krzak 2006, p. 567.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 181.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 Niehorster 2013b.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 264.

- 1 2 3 4 5 U.S. Army 1986, p. 53.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, p. 37.

- ↑ Geografski institut JNA 1952, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Terzić 1982, p. 258.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Terzić 1982, p. 257.

- 1 2 3 Terzić 1982, p. 256.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 256–258.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 34–43.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 64.

- ↑ Trevor-Roper 1964, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Barefield 1993, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 256–259.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 258–260.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 269.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 259–260.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army 1986, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Krzak 2006, p. 583.

- 1 2 3 Terzić 1982, p. 293.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Shores, Cull & Malizia 1987, p. 201.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 265.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Terzić 1982, p. 308.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Terzić 1982, p. 312.

- ↑ Shores, Cull & Malizia 1987, p. 213.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 308–310.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 329.

- 1 2 3 4 Terzić 1982, p. 331.

- 1 2 3 Terzić 1982, p. 330.

- ↑ Shores, Cull & Malizia 1987, p. 215.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 50–52.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 332.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 333.

- 1 2 3 Terzić 1982, p. 348.

- 1 2 3 4 Terzić 1982, p. 345.

- 1 2 3 Terzić 1982, p. 347.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Terzić 1982, p. 346.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, p. 68.

- ↑ Krzak 2006, pp. 583–584.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 361.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army 1986, p. 58.

- ↑ Krzak 2006, p. 585.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 55.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 368.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 367.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 367–368.

- ↑ Stein 1984, p. 295.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 52–53.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army 1986, p. 60.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 364–366.

- 1 2 3 Terzić 1982, p. 366.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 364.

- 1 2 3 4 Terzić 1982, p. 388.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 386.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 386–387.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 387.

- 1 2 3 Terzić 1982, p. 402.

- 1 2 Terzić 1982, p. 415.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 430.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, p. 431.

- ↑ Terzić 1982, pp. 444–445.

- ↑ U.S. Army 1986, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 89–95.

References

Books

- Brayley, Martin; Chappell, Mike (2001). British Army 1939–45 (1): North-West Europe. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-052-0.

- Figa, Jozef (2004). "Framing the Conflict: Slovenia in Search of Her Army". Civil-Military Relations, Nation Building, and National Identity: Comparative Perspectives. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-04645-2 – via Questia. (Subscription required (help)).

- Geografski institut JNA (1952). "Napad na Jugoslaviju 6 Aprila 1941 godine" [The Attack on Yugoslavia of 6 April 1941]. Istorijski atlas oslobodilačkog rata naroda Jugoslavije [Historical Atlas of the Yugoslav Peoples Liberation War]. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Vojnoistorijski institut JNA [Military History Institute of the JNA].

- Hoptner, J.B. (1963). Yugoslavia in Crisis, 1934–1941. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. OCLC 404664 – via Questia. (Subscription required (help)).

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Shores, Christopher F.; Cull, Brian; Malizia, Nicola (1987). Air War for Yugoslavia, Greece, and Crete, 1940–41. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-07-6.

- Stein, George H. (1984). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–45. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9275-0.

- Terzić, Velimir (1982). Slom Kraljevine Jugoslavije 1941: Uzroci i posledice poraza [The Collapse of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1941: Causes and Consequences of Defeat] (in Serbo-Croatian). 2. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Narodna knjiga. OCLC 10276738.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1964). Hitler's War Directives: 1939–1945. London, England: Sidgwick and Jackson. ISBN 978-1-84341-014-0.

- U.S. Army (1986) [1953]. The German Campaigns in the Balkans (Spring 1941). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 16940402. CMH Pub 104-4.

Journals and papers

- Barefield, Michael R. (May 1993). "Overwhelming Force, Indecisive Victory: The German Invasion of Yugoslavia, 1941". Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 32251055.

- Krzak, Andrzej (2006). "Operation "Marita": The Attack Against Yugoslavia in 1941". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 19 (3): 543–600. ISSN 1351-8046. doi:10.1080/13518040600868123.

Websites

- Niehorster, Leo (2013a). "Royal Yugoslav Armed Forces Ranks". Dr. Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- Niehorster, Leo (2013b). "Balkan Operations Order of Battle Royal Yugoslavian Army 4th Army 6th April 1941". Dr. Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 12 May 2015.