Royal Engineers

| Royal Engineers | |

|---|---|

|

Cap badge of the Corps of Royal Engineers. | |

| Active | 1716–present |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Size | 15 Regiments |

| Part of | Commander Land Forces |

| Garrison/HQ | Chatham, Kent, England |

| Motto(s) | Ubique Quo Fas Et Gloria Ducunt ("Everywhere That Right And Glory Lead"; in Latin fas implies "sacred duty")[1] |

| March | Wings (Quick march) |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Brigadier D L D Bigger |

| Chief Royal Engineer | Lieutenant General Sir Mark Mans KCB, CBE, DL |

| Insignia | |

| Tactical recognition flash |

|

|

| Arms of the British Army |

|---|

| Combat Arms |

|

|

| Combat Support Arms |

| Combat Services |

|

|

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually just called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the Sappers, is one of the corps of the British Army. It is highly regarded throughout the military, and especially the Army.

It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is headed by the Chief Royal Engineer. The Regimental Headquarters and the Royal School of Military Engineering are in Chatham in Kent, England. The corps is divided into several regiments, barracked at various places in the United Kingdom and around the world.

History

The Royal Engineers trace their origins back to the military engineers brought to England by William the Conqueror, specifically Bishop Gundulf of Rochester Cathedral, and claim over 900 years of unbroken service to the crown. Engineers have always served in the armies of the Crown; however, the origins of the modern corps, along with those of the Royal Artillery, lie in the Board of Ordnance established in the 15th century.[2]

In Woolwich in 1716, the Board formed the Royal Regiment of Artillery and established a Corps of Engineers, consisting entirely of commissioned officers. The manual work was done by the Artificer Companies, made up of contracted civilian artisans and labourers. In 1772, a Soldier Artificer Company was established for service in Gibraltar, the first instance of non-commissioned military engineers. In 1787, the Corps of Engineers was granted the Royal prefix and adopted its current name and in the same year a Corps of Royal Military Artificers was formed, consisting of non-commissioned officers and privates, to be officered by the RE. Ten years later the Gibraltar company, which had remained separate, was absorbed and in 1812 the name was changed to the Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners.[2]

The Corps has no battle honours. In 1832, the regimental motto, Ubique Quo Fas Et Gloria Ducunt ("Everywhere That Right And Glory Lead"; in Latin fas implies "sacred duty"), was granted.[1] The motto signified that the Corps had seen action in all the major conflicts of the British Army and almost all of the minor ones as well.[3][4]

In 1855 the Board of Ordnance was abolished and authority over the Royal Engineers, Royal Sappers and Miners and Royal Artillery was transferred to the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, thus uniting them with the rest of the Army. The following year, the Royal Engineers and Royal Sappers and Miners became a unified corps as the Corps of Royal Engineers and their headquarters were moved from the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, to Chatham, Kent.[2]

The re-organisation of the British military that began in the mid-Nineteenth Century and stretched over several decades included the reconstitution of the Militia, the raising of the Volunteer Force, and the ever-closer organisation of the part-time forces with the regular army.[5] The old Militia had been an infantry force, other than the occasional employment of Militiamen to man artillery defences and other roles on an emergency basis. This changed in 1861, with the conversion of some units to artillery roles. Militia and Volunteer Engineering companies were also created, beginning with the conversion of the militia of Anglesey and Monmouthshire to engineers in 1877. The Militia and Volunteer Force engineers supported the regular Royal Engineers in a variety of roles, including operating the boats required to tend the submarine mine defences that protected harbours in Britain and its empire. These included a submarine mining militia company that was authorised for Bermuda in 1892, but never raised, and the Bermuda Volunteer Engineers that wore Royal Engineers uniforms and replaced the regular Royal Engineers companies withdrawn from the Bermuda Garrison in 1928.[6][7] The various part-time reserve forces were amalgamated into the Territorial Force in 1908,[8] which was retitled the Territorial Army after the First World War, and the Army Reserve in 2014.[9]

In 1911 the Corps formed its Air Battalion, the first flying unit of the British Armed Forces. The Air Battalion was the forerunner of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force.[10]

In 1915, in response to German mining of British trenches under the then static siege conditions of the First World War, the corps formed its own tunnelling companies. Manned by experienced coal miners from across the country, they operated with great success until 1917, when after the fixed positions broke, they built deep dugouts such as the Vampire dugout to protect troops from heavy shelling.[11]

Before the Second World War, Royal Engineers recruits were required to be at least 5 feet 4 inches tall (5 feet 2 inches for the Mounted Branch). They initially enlisted for six years with the colours and a further six years with the reserve or four years and eight years. Unlike most corps and regiments, in which the upper age limit was 25, men could enlist in the Royal Engineers up to 35 years of age. They trained at the Royal Engineers Depot in Chatham or the RE Mounted Depot at Aldershot.[12]

The Royal Engineers Museum is in Gillingham in Kent.[13]

Significant constructions

Britain having acquired an Empire, it fell to the Royal Engineers to conduct some of the most significant "civil" engineering schemes around the world. Some examples of great works of the era of empire can be found in A. J. Smithers's book Honourable Conquests.[14]

British Columbia

The Royal Engineers, Columbia Detachment, commanded by Richard Clement Moody, was responsible for the foundation and settlement of British Columbia as the Colony of British Columbia.[15][16]

Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is one of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, recognisable the world over. Since its opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from every kind of performance genre have appeared on its stage. Each year it hosts more than 350 performances including classical concerts, rock and pop, ballet and opera, tennis, award ceremonies, school and community events, charity performances and lavish banquets. The Hall was designed by Captain Francis Fowke and Major-General Henry Y. D. Scott of the Royal Engineers and built by Lucas Brothers.[17] The designers were heavily influenced by ancient amphitheatres, but had also been exposed to the ideas of Gottfried Semper while he was working at the Victoria and Albert Museum.[18]

Indian infrastructure

Much of the British colonial era infrastructure of India, of which elements survive today, was created by engineers of the three presidencies' armies and the Royal Engineers. Lieutenant (later General Sir) Arthur Thomas Cotton (1803–99), Madras Engineers, was responsible for the design and construction of the great irrigation works on the river Cauvery, which watered the rice crops of Tanjore and Trichinopoly districts in the late 1820s. In 1838 he designed and built sea defences for Vizagapatam. He masterminded the Godavery Delta project where 720,000 acres (2,900 km2) of land were irrigated and 500 miles (800 km) of land to the port of Cocanada was made navigable in the 1840s. Such regard for his lasting legacy was shown when in 1983, the Indian Government erected a statue in his memory at Dowleswaram.[19]

Other irrigation and canal projects included the Ganges Canal, where Colonel Sir Colin Scott-Moncrieff (1836–1916) acted as the Chief Engineer and made modifications to the original work. Among other engineers trained in India, Scott-Moncrieff went on to become Under Secretary of State Public Works, Egypt where he restored the Nile barrage and irrigation works of Lower Egypt.[20]

Rideau Canal

The construction of the Rideau Canal was proposed shortly after the War of 1812, when there remained a persistent threat of attack by the United States on the British colony of Upper Canada. The initial purpose of the Rideau Canal was military, as it was intended to provide a secure supply and communications route between Montreal and the British naval base in Kingston, Ontario. Westward from Montreal, travel would proceed along the Ottawa River to Bytown (now Ottawa), then southwest via the canal to Kingston and out into Lake Ontario. The objective was to bypass the stretch of the St. Lawrence River bordering New York State, a route which would have left British supply ships vulnerable to attack or a blockade of the St. Lawrence. The construction of the canal was supervised by Lieutenant-Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers. In 2007 it was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site recognizing it as a work of human creative genius. The Rideau Canal was recognized as the best preserved example of a slack water canal in North America demonstrating the use of European slackwater technology in North America on a large scale. Lt. Denison was one of the junior Royal Engineers who worked under Lt. Colonel John By, RE on the Rideau Canal in Upper Canada (1826–1832). Of note, Denison carried out experiments under the direction of Lt. Col. By to determine the strength, for construction purposes of the old growth timber in the vicinity of Bytown. His findings were published by the Institution of Civil Engineers in England who bestowed upon him the prestigious Telford Medal.[21]

Dover's Western Heights

The Western Heights of Dover are one of the most impressive fortifications in Britain. They comprise a series of forts, strong points and ditches, designed to protect the United Kingdom from invasion. They were created to augment the existing defences and protect the key port of Dover from both seaward and landward attack. First given earthworks in 1779 against the planned invasion that year, the high ground west of Dover, England, now called Dover Western Heights, was properly fortified in 1804 when Lieutenant-Colonel William Twiss was instructed to modernise the existing defences. This was part of a huge programme of fortification in response to Napoleon's planned invasion of the United Kingdom. To assist with the movement of troops between Dover Castle and the town defences Twiss made his case for building the Grand Shaft in the cliff:

"... the new barracks. ... are little more than 300 yards horizontally from the beach. ... and about 180 feet (55 m) above high-water mark, but in order to communicate with them from the centre of town, on horseback the distance is nearly a mile and a half and to walk it about three-quarters of a mile, and all the roads unavoidably pass over ground more than 100 feet (30 m) above the barracks, besides the footpaths are so steep and chalky that a number of accidents will unavoidably happen during the wet weather and more especially after floods. I am therefore induced to recommend the construction of a shaft, with a triple staircase ... the chief objective of which is the convenience and safety of troops ... and may eventually be useful in sending reinforcements to troops or in affording them a secure retreat."[22]

Twiss's plan was approved and building went ahead. The shaft was to be 26 feet (7.9 m) in diameter, 140 feet (43 m) deep with a 180 feet (55 m) gallery connecting the bottom of the shaft to Snargate Street, and all for under an estimated £4000. The plan entailed building two brick-lined shafts, one inside the other. In the outer would be built a triple staircase, the inner acting as a light well with "windows" cut in its outer wall to illuminate the staircases. Apparently, by March 1805 only 40 feet (12 m) of the connecting gallery was left to dig and it is probable that the project was completed by 1807.[22]

Pentonville Prison

Two Acts of Parliament allowed for the building of Pentonville Prison for the detention of convicts sentenced to imprisonment or awaiting transportation. Construction started on 10 April 1840 and was completed in 1842. The cost was £84,186 12s 2d. Captain (later Major General Sir) Joshua Jebb designed Pentonville Prison, introducing new concepts such as single cells with good heating, ventilation and sanitation.[23]

Boundary Commissions

Although mapping by what became the Ordnance Survey was born out of military necessity it was soon realised that accurate maps could be also used for civic purposes. The lessons learnt from this first boundary commission were put to good use around the world where members of the Corps have determined boundaries on behalf of the British as well as foreign governments; some notable boundary commissions include:[24]

- 1839 – Canada-United States

- 1858 – Canada-United States (Captain (later General Sir) John Hawkins RE)

- 1856 and 1857 – Russo-Turkish (Lieutenant Colonel (later Sir) Edward Stanton RE)

- 1857 – Russo-Turkish (Colonel (later Field Marshal Sir) Lintorn Simmons RE)

- 1878 – Bulgarian

- 1880 – Græco-Turkish (Major (later Major General Sir) John Ardagh RE)

- 1884 – Russo-Afghan (Captain (later Colonel Sir) Thomas Holdich RE)

- 1894 – India-Afghanistan (Captain (later Colonel Sir) Thomas Holdich RE)

- 1902 – Chile-Argentine (Colonel Sir Delme Radcliffe RE)

- 1911 – Peru-Bolivia (Major A. J. Woodroffe RE)

Much of this work continues to this day. The reform of the voting franchise brought about by the Reform Act (1832), demanded that boundary commissions were set up. Lieutenants Dawson and Thomas Drummond (1797–1839), Royal Engineers, were employed to gather the statistical information upon which the Bill was founded, as well as determining the boundaries and districts of boroughs. It was said that the fate of numerous boroughs fell victim to the heliostat and the Drummond light, the instrument that Drummond invented whilst surveying in Ireland.[25]

Abney Level

An Abney level is an instrument used in surveying which consists of a fixed sighting tube, a movable spirit level that is connected to a pointing arm, and a protractor scale. The Abney level is an easy to use, relatively inexpensive, and when used correctly an accurate surveying tool. The Abney level was invented by Sir William de Wiveleslie Abney (1843–1920) who was a Royal Engineer, an English astronomer and chemist best known for his pioneering of colour photography and colour vision. Abney invented this instrument under the employment of the Royal School of Military Engineering in Chatham, England, in the 1870s.[26]

H.M. Dockyards

In 1873, Captain Henry Brandreth RE was appointed Director of the Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, later the Admiralty Works Department. Following this appointment many Royal Engineer officers superintended engineering works at Royal Navy Dockyards in various parts of the world, including the Royal Naval Dockyard, Bermuda.[27]

Chatham Dockyard

Chatham, being the home of the Corps, meant that the Royal Engineers and the Dockyard had a close relationship since Captain Brandreth's appointment. At the Chatham Dockyard, Captain Thomas Mould RE designed the iron roof trusses for the covered slips, 4, 5 and 6. Slip 7 was designed by Colonel Godfrey Greene RE on his move to the Corps from the Bengal Sappers & Miners. In 1886 Major Henry Pilkington RE was appointed Superintendent of Engineering at the Dockyard, moving on to Director of Engineering at the Admiralty in 1890 and Engineer-in-Chief of Naval Loan Works, where he was responsible for the extension of all major Dockyards at home and abroad.[28]

Trades

All members of the Royal Engineers are trained combat engineers and all sappers (privates) and non-commissioned officers also have another trade. These trades include: air conditioning fitter, electrician, general fitter, plant operator mechanic, plumber, bricklayer, plasterer / painter, carpenter & joiner, fabricator, building materials technician, design draughtsman, electrical & mechanical draughtsman, geographic support technician, survey engineer, armoured engineer, driver, engineer IT, engineer logistics specialist, amphibious engineer, bomb disposal specialist, diver or search specialist.[29] They may also undertake the specialist selection and training to qualify as Commandos or Military Parachutists. Women are eligible for all Royal Engineer specialities.[30]

Units

Brigades & Groups

- 8th Engineer Brigade

- 12 Force Support Group[31]

- 21 Engineer Regiment

- 32 Engineer Regiment

- 36 Engineer Regiment

- 39 Engineer Regiment

- 25 (Close Support) Engineer Group

- 22 Engineer Regiment

- 26 Engineer Regiment

- 35 Engineer Regiment

- 29 EOD & Search Group[32]

- 33 Engineer Regiment (EOD)

- 101 Engineer Regiment (EOD)

- 11 EOD Regiment RLC

- 1 Military Working Dog Regiment

- 170 (Infrastructure Support) Engineer Group (previously Military Works Force)[33]

- HQ Works Group

- Royal Engineers Specialist Advisory Team (RESAT)

- Technical Information Centre Royal Engineers

- 62 Works Group (Water utilities, water development and well drilling)

- 506 STRE (Water Infrastructure) (Volunteers)

- 519 STRE (Works)

- 523 STRE (Works)

- 521 STRE (Water Development)

- 63 Works Group (Electrical power generation and distribution)

- 504 STRE (Power Infrastructure) (Volunteers)

- 518 STRE (Works)

- 528 STRE (Power)

- 535 STRE (Works)

- 64 Works Group (Fuels, fuel production and distribution) A written statement in December 2016 stated that it will be rationalised, with all manpower in this unit being redeployed to other areas of the British Army.[34]

- 503 STRE (Fuel Infrastructure) (Volunteers)

- 516 STRE (Fuels)

- 524 STRE (Works)

- 527 STRE (Works)

- 65 (Volunteers) Works Group (Civilian infrastructure, railway and ports infrastructure)

- 503 STRE (Fuels)

- 504 STRE (Power)

- 506 STRE (Water)

- 507 STRE (Rail)

- 509 STRE (Ports)

- 510 STRE (Air)

- 66 Works Group (Air Support and geotechnical engineering)

- 510 STRE (Air Support)(Volunteers)

- 517 STRE (Works)

- 522 STRE (Works)

- 530 STRE (Materials)

- 67 Works Group

- 502 STRE (Works)

- 505 STRE (Works)

- HQ Works Group

- 12 Force Support Group[31]

Regiments

- 21 Engineer Regiment:[35]

- 7 Headquarters and Support Squadron

- 1 Field Squadron Squadron

- 4 Field Squadron Squadron

- 103 (1st Newcastle) Field Squadron (Newcastle/Sunderland)

- 106 (West Riding) Field Squadron (Sheffield/Bradford)

- Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers Light Aid Detachment

- 22 Engineer Regiment:[36]

- 6 Headquarters and Support Squadron

- 3 Armoured Engineer Squadron

- 5 Armoured Engineer Squadron

- 52 Armoured Engineer Squadron

- Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers Light Aid Detachment

- 23 Parachute Engineer Regiment – part of 16 Air Assault Brigade[37]

- 12 (Nova Scotia) Headquarters and Support Squadron (Air Assault)

- 9 Parachute Squadron

- 51 Parachute Squadron

- 299 Para Field Squadron (Reserve) Wakefield/Hull/Gateshead

- 24 Commando Engineer Regiment – part of 3 Commando Brigade, Royal Marines (based at Chivenor). Formed in 2008 as part of the Delivering Security in a Changing World review, when the engineering support for 3 Commando Brigade was increased to a full regiment.[38]

- 54 Commando Squadron

- 59 Commando Squadron

- 131 Commando Squadron (Reserve) - based in Kingsbury, Plymouth, Birmingham and Bath

- 26 Engineer Regiment:[39]

- 38 Headquarters and Support Squadron

- 8 Armoured Engineer Squadron

- 30 Armoured Engineer Squadron

- 33 Armoured Engineer Squadron

- 32 Engineer Regiment:[40]

- 2 Headquarters and Support Squadron

- 26 Armoured Engineer Squadron

- 31 Armoured Engineer Squadron

- 33 Engineer Regiment (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) (Hybrid Regiment with Regular & Army Reserve Squadrons):[41]

- 35 Engineer Regiment:[42] Disbandment of this unit was announced in December 2016[34]

- 36 Engineer Regiment (Search):[43]

- 50 Headquarters & Support Squadron

- 20 Field Squadron

- 69 Gurkha Field Squadron

- 70 Gurkha Field Support Squadron

- 39 Engineer Regiment:[44]

- 60 Headquarters and Support Squadron (Air Support)

- 10 Field Squadron (Air Support)

- 34 Field Squadron (Air Support)

- 48 Field Squadron (Air Support)

- 53 Field Squadron (Air Support)

- REME Workshop

- 42 Engineer Regiment (Geographic):[45]

- 13 Geographic Squadron

- 14 Geographic Squadron

- 16 Geographic Support Squadron

- 135 Geographic Squadron (Reserve)

- 71 Engineer Regiment[46]

- 10 (Orkney) Troop - Kirkwall

- RHQ [Leuchars Station]

- 102 Field Squadron [Paisley/Barnsford Bridge]

- 124 Field Support Squadron [Cumbernauld, Leuchars, Kinloss and Orkney]

- 236 Troop - Kinloss Barracks

- 591 (Antrim Artillery) Field Squadron [Bangor, NI]

- 75 Engineer Regiment (Field)[47]

- 107 (Lancashire and Cheshire) Field Squadron [Birkenhead]

- 202 Field Support Squadron [Manchester]

- 412 Amphibious Engineer Troop(Volunteers) Reserve ( MINDEN, GERMANY )

- 101 (City of London) Engineer Regiment (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) [Hybrid Regiment with Regular & Army Reserve Squadrons]:[48]

- Royal Monmouthshire Royal Engineers (Militia)[49]

- RHQ Troop [Monmouth]

- 100 Field Squadron [Cwmbran/Bristol/Cardiff/Swansea]

- 225 Field Squadron [Birmingham]

- Jersey Field Squadron [St Helier]

- Reserve EOD Regiment (to be formed)[34]

- Engineer and Logistic Staff Corps (Volunteers)[50]

- The Nottinghamshire Band of The Royal Engineers [Nottingham][51]

The Royal School of Military Engineering

The Royal School of Military Engineering is the British Army's Centre of Excellence for Military Engineering, Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD), and counter terrorist search training. Located on several sites in Chatham, Kent, Camberley in Surrey and Bicester in Oxfordshire the Royal School of Military Engineering offers superb training facilities for the full range of Royal Engineer skills. The RSME was founded by Major (later General Sir) Charles Pasley, as the Royal Engineer Establishment in 1812.[52] It was renamed the School of Military Engineering in 1868 and granted the "Royal" prefix in 1962.[53]

- Royal School of Military Engineering[54]

- Combat Engineer School

- 3 Royal School of Military Engineering Regiment

- 55 Training Squadron Royal Engineers

- 57 Training Squadron Royal Engineers

- 63 Training Support Squadron Royal Engineers

- Communication Information Systems Wing

- 3 Royal School of Military Engineering Regiment

- Construction Engineer School

- 1 Royal School of Military Engineering Regiment

- 24 Training Squadron Royal Engineers

- 36 Training Squadron Royal Engineers

- Civil Engineering Wing

- Electrical and Mechanical Wing

- 1 Royal School of Military Engineering Regiment

- Royal Engineers Warfare Wing (Founded in 2011 and split between Brompton Barracks, Chatham and Gibraltar Barracks at Minley in Hampshire, this is the product of the amalgamation between Command Wing, where Command and Tactics were taught and Battlefield Engineering Wing, where combat engineering training was facilitated.)

- United Kingdom Mine Information and Training Centre

- Defence Explosive Munitions and Search School (formally Defence EOD School and the National Search Centre)

- Combat Engineer School

- 28 Training Squadron, Army Training Regiment[55]

- Diving Training Unit (Army), (DTU(A))[56]

- Band of the Corps of Royal Engineers (The Band are part of the Corps of Army Music, but wear the uniform of the Royal Engineers)[57]

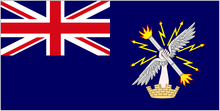

Corps' Ensign

The Royal Engineers, Ports Section, operated harbours and ports for the army and used mainly specialised vessels such as tugs and dredgers. During the Second World War the Royal Engineers' Blue Ensign was flown from the Mulberry harbours.[58]

Bishop Gundulf, Rochester and King's Engineers

Bishop Gundulf, a monk from the Abbey of Bec in Normandy came to England in 1070 as Archbishop Lafranc's assistant at Canterbury. His talent for architecture had been spotted by King William I and was put to good use in Rochester where he was sent as Bishop in 1077. Almost immediately the King appointed him to supervise the construction of the White Tower, now part of the Tower of London in 1078. Under William Rufus he also undertook building work on Rochester Castle. Having served three Kings of England and earning "the favour of them all", Gundulf is accepted as the first "King's Engineer".[59]

The Institution of Royal Engineers

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1148711.jpg)

The Institution of Royal Engineers, the professional institution of the Corps of Royal Engineers, was established in 1875 and in 1923 it was granted its Royal Charter by King George V. The Institution is collocated with the Royal Engineers Museum, within the grounds of the Royal School of Military Engineering at Brompton in Chatham, Kent.[60]

The History of the Corps of Royal Engineers is currently in its 12th volume. The first two volumes were written by Major General Whitworth Porter and published in 1889.[61]

The Sapper is published by the Royal Engineers Central Charitable Trust and is a monthly magazine for all ranks.[62]

The Royal Engineers' Association

The Royal Engineers Association was formed to promote and support the Corps among members of the Association in the following ways:[63]

- By fostering esprit de corps and a spirit of comradeship and service.

- By maintaining an awareness of Corps traditions.

- By acting as a link between serving and retired members of the Corps.

- To provide financial and other assistance to serving and former members of the Corps, their wives, widows and dependants who are in need through poverty.

- To make grants, within Association guidelines, to the Army Benevolent Fund and to other charities which further the objectives of the Association.

Royal Engineers' Yacht Club

The Royal Engineers' Yacht Club, which dates back to 1812, promotes the skill of watermanship in the Royal Engineers.[64]

The Royal Engineers Amateur Football Club

The club was founded in 1863, under the leadership of Major Francis Marindin. Sir Frederick Wall, who was the secretary of The Football Association 1895–1934, stated in his memoirs that the "combination game" was first used by the Royal Engineers A.F.C. in the early 1870s.[65][66][67] Wall states that the "Sappers moved in unison" and showed the "advantages of combination over the old style of individualism".

FA Cup

The Engineers played in the first-ever FA Cup Final, losing 1–0 at Kennington Oval on 16 March 1872, to regular rivals Wanderers.[68] They also lost the 1874 Final, to Oxford University A.F.C..

Their greatest triumph was the 1874–75 FA Cup.[68] In the final against Old Etonians, they drew 1–1 with a goal from Renny-Tailyour and went on to win the replay 2-0 with a goal each from Renny-Tailyour and Stafford.[69]

The winning side was:[69]

- Capt. W. Merriman; Lt. G.H. Sim; Lt. G.C. Onslow; Lt. R.M. Ruck; Lt. P.G. von Donop; Lt. C.K. Wood; Lt. H.E. Rawson; Lt. W.F.H. Stafford; Lt. H. W. Renny-Tailyour; Lt. A. Mein; and Lt. C. Wingfield-Stratford.

A match programme from an Old Etonians FA Cup Final sold in an auction held at Sotheby's, New Bond street. The game was played at Kennington Oval on 25 March 1882 and shot past the £20,000-25,000 estimate to hit £30,000. It was bought at the sale on 13–14 May 2014 appropriately enough, by the Old Etonians Football Club to go on display at Eton College's Museum of Eton Life.[70]

A sword owned by Royal Engineers defender G.H. Sim who played in two FA Cup Finals in 1875 against the Old Etonians is going under the hammer at John Mullock auctions on 15 April 2015.[71] John Mullock has been quoted as stating "Any FA Cup artifacts pre-1900s are like hen's teeth".[72]

Their last FA Cup Final appearance came in 1878, again losing to the Wanderers.[68] They last participated in 1882–83 FA Cup, losing 6–2 in the fourth round to Old Carthusians F.C..[68]

The Engineers' Depot Battalion won the FA Amateur Cup in 1908.[73]

On 7 November 2012, the Royal Engineers played against the Wanderers in a remake of the 1872 FA Cup Final at The Oval.[74] Unlike the actual final, the Engineers won, and by a large margin, 7–1 being the final score.[75]

Rugby

The Army were represented in the very first international by two members of the Royal Engineers, both playing for England, Lieutenant Charles Arthur Crompton RE and Lieutenant Charles Sherrard RE.[76]

Successor units

Several units have been formed from the Royal Engineers.

- The Air Battalion Royal Engineers (formed 1911) was the precursor of the Royal Flying Corps (formed 1912) which evolved into the Royal Air Force in 1918.[10]

- The Telegraph Troop, founded in 1870,[77]:121 became the Telegraph Battalion Royal Engineers who then became the Royal Engineers Signals Service, which in turn became the independent Royal Corps of Signals in 1920.[78]

- The Royal Engineers were responsible for railway and inland waterway transport, port operations and movement control until 1965, when these functions were transferred to the new Royal Corps of Transport. (See also Railway Operating Division.)[79]

- In 1913, the Army Post Office Corps (formed in 1882) and the Royal Engineers Telegraph Reserve (formed in 1884) amalgamated to form the Royal Engineers (Postal Section) Special Reserve. This later became the Defence Postal and Courier Service and remained part of the RE until the formation of the Royal Logistic Corps in 1993 – see (British Forces Post Office).[80]

Notable personnel

- Category:Royal Engineers soldiers

- Category:Royal Engineers officers

Engineering equipment

Order of precedence

| Preceded by Royal Regiment of Artillery |

Order of Precedence | Succeeded by Royal Corps of Signals |

Decorations

Victoria Cross

The following Royal Engineers have been awarded the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.[81]

- Tom Edwin Adlam, 1916, Thiepval, France

- Adam Archibald, 1918, Ors, France

- Fenton John Aylmer, 1891, Nilt Fort, India

- Mark Sever Bell, 1874, Battle Of Ordashu, Ashanti (now Ghana)

- John Rouse Merriott Chard, 1879, Rorke's Drift, South Africa

- Brett Mackay Cloutman, 1918, Pont-Sur-Sambre, France

- Clifford Coffin, 1917, Westhoek, Belgium

- James Morris Colquhoun Colvin, 1897, Mohmand Valley, India

- James Lennox Dawson, 1915, Hohenzollern Redoubt, France

- Robert James Thomas Digby-Jones, 1900, Ladysmith, South Africa

- Thomas Frank Durrant, 1942, St. Nazaire, France

- Howard Craufurd Elphinstone, 1855, Sevastopol, Crimea

- George de Cardonnel Elmsall Findlay, 1918, Catillon, France

- Gerald Graham, 1855, Sevastopol, Crimea

- William Hackett, 1916, Givenchy, France

- Reginald Clare Hart, 1879, Bazar Valley, Afghanistan

- Lanoe Hawker, 1915 {While serving with the RFC}

- Charles Alfred Jarvis, 1914, Jemappes, Belgium

- Frederick Henry Johnson, 1915, Hill 70, France

- William Henry Johnston, 1914, Missy, France

- Frank Howard Kirby, 1900, Delagoa Bay Railway, South Africa

- Cecil Leonard Knox, 1918, Tugny, France

- Edward Pemberton Leach, 1879, Maidanah, Afghanistan

- Peter Leitch, 1855, Sevastopol, Crimea

- William James Lendrim, 1855, Sevastopol, Crimea

- Wilbraham Oates Lennox, 1854, Sevastopol, Crimea

- Henry MacDonald, 1855, Sevastopol, Crimea

- Cyril Gordon Martin, 1915, Spanbroekmolen on the Messines Ridge, Belgium

- James McPhie, 1918, Aubencheul-Au-Bac, France

- Philip Neame, 1914, Neuve Chapelle, France

- John Perie, 1855, Sevastopol, Crimea

- Claude Raymond, 1945, Talaku, Burma (now Myanmar)

- John Ross, 1855, Sevastopol, Crimea

- Michael Sleavon, 1858, Jhansi, India

- Arnold Horace Santo Waters, 1918, Ors, France

- Thomas Colclough Watson, 1897, Mamund Valley, India

- Theodore Wright, 1914, Mons, Belgium

The Sapper VCs

In 1998, HMSO published an account of the 55 British and Commonwealth 'Sappers' who have been awarded the Victoria Cross. The book was written by Colonel GWA Napier, former Royal Engineers officer and a former Director of the Royal Engineers Museum. The book defines a 'Sapper' as any "member of a British or Empire military engineer corps, whatever their rank, speciality or national allegiance", and is thus not confined to Royal Engineers.[82]

Memorials

- Rochester Cathedral, Kent has major historical links with the Corps and contains many memorials including stained glass, mosaics and plaques. The cathedral hosts services on the annual Corps Memorial Weekend and is supported by the Corps on Remembrance Sunday.

- Royal Engineers First World War memorial at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre

- National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, Staffordshire

- The memorial to the Royal Engineers at Arromanches, the site of the Mulberry Harbours during the Second World War[83]

See also

- Mine Information Training Centre

- Royal Engineers, Columbia Detachment

- Bermuda Volunteer Engineers, a territorial unit that replaced the Regular Army RE companies of the Bermuda Garrison in 1930. Disbanded 1946.

- Canadian Military Engineers, created in 1903 to provide a replacement for the RE in Canada

- List of international professional associations

- The Association of British Columbia Land Surveyors

- Institution of Engineers

- AVRE

References

- 1 2 "No. 18952". The London Gazette. 10 July 1832. p. 1583.

- 1 2 3 "A brief history of the Royal Engineers" (PDF). The Masons Livery Company. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ British Army Website: Corps of Royal Engineers Badges and Emblems

- ↑ Anon (1916) Regimental Nicknames and Traditions of the British Army. 5th Ed. London: Gale and Polden Ltd. p. 36

- ↑ War Office Circular, 12 May 1859, published in The Times, 13 May.

- ↑ Army Notes. Royal United Services Institution Journal, Volume 73, Issue 490, 1928

- ↑ UK Parliament house of commons debate: ARMY ESTIMATES, 1928. 8 March 1928. vol 214 cc1261-310 1261

- ↑ Tony Mason and Eliza Ried, Sport and the Military: The British Armed Forces 1880–1960 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) p.39

- ↑ "Territorial Army 'to be renamed the Army Reserve'". BBC News. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- 1 2 "The Air Battalion". The RAF Museum. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ "Tunnelling Companies in the Great War". Tunnellers Memorial. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ War Office, His Majesty's Army, 1938

- ↑ "Royal Engineers Museum". British listed buildings. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ Smithers, A. J. (1991). Honourable Conquests: An Account of the Enduring Work of the Royal Engineers Throughout the Empire. Pen & Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85052-725-4.

- ↑ "The Royal Engineers: Colonel Richard Clement Moody". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Volume 90, Issue 1887, 1887, pp. 453-455, OBITUARY. MAJOR-GENERAL RICHARD CLEMENT MOODY, R.E., 1813-1181.

- ↑ "Charles Lucas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2004. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ "Royal Albert Hall". Famous Wonders. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ Cotton, Lady (1900). General Sir Arthur Cotton, RE, KCSI: His Life and Work.

- ↑ Scott-Moncrieff, Sir Colin Campbell. The Indian Biographical Dictionary. 1915.

- ↑ Watson, Ken. "Bye By: The Story of Lieutenant-Colonel John By, R.E. and his fall from grace". Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- 1 2 Ingleton, Roy (2012). Fortress Kent. Pen & Sword Military. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-1848848887.

- ↑ "Joshua Jebb on Pentonville Prison, London". Elton Engineering Books. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ↑ Fenwick, SC. "Boundary Commissions – 1832–1911". Corps History – Part 12: Engineers in a Civic role (1820–1911). Royal Engineers Museum.

- ↑ "Demonstrations 19 – Limelight". Leeds University. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Abney, William de Wiveleslie. Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. 2014. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-1-4419-9917-7.

- ↑ "Woolwich Dockyard Area" (PDF). University College London. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Chatham Royal Naval Barracks" (PDF). Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Your guide to the Royal Engineers" (PDF). Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Army life: your guide to the Royal Engineers" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. p. 3. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ "12 (Air Support) Engineer Group webpage".

- ↑ "29 EOD & Search Group webpage".

- ↑ "170 (Infrastructure Support) Engineer Group webpage".

- 1 2 3 "Strategic Defence and Security Review - Army:Written statement - HCWS367 - UK Parliament". Parliament.uk. 2014-12-04. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- ↑ "21 Engineer Regiment". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "22 Engr Regt". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "23 Engr Regt (Air Assault)". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ "24 (Commando) Engineer Regiment". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "26 Engr Regt". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "32 Engr Regt". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "Bomb Disposal and Search Specialists". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "35 Engr Regt". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "36 Engr Regt". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "39 Engr Regt". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "42 Engr Regt". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "71 Engineer Regiment". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "75 Engineer Regiment". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ "101 Engr Regt (EOD)". British Army. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "Royal Monmouthshire RE". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ↑ "Staff Corps Membership". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Nottinghamshire Band of The Royal Engineers". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Corps History Part 6 Royal Engineers Museum

- ↑ Corps History Part 17 Royal Engineers Museum

- ↑ "Royal School of Military Engineering". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Army Training Centre Pirbright say farewell to 76 Battery Royal Artillery". Royal Artillery Association. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Diving Training Unit (Army)". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Band of the Corps of Royal Engineers". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Flag, Blue Ensign: Royal Engineers". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "The Towers that Gundulf Built". Kate Shrewsday. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "The Institution of Royal Engineers". Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Institution of Royal Engineers (InstRE)". Articles. Royal Engineers Museum. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ↑ "The Sapper Magazine". Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Royal Engineers' Association". Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Sapper Sailing". Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Wall, Sir Frederick (2005). 50 Years of Football, 1884–1934. Soccer Books Limited. ISBN 1-86223-116-8.

- ↑ Cox, Richard (2002) The Encyclopaedia of British Football, Routledge, United Kingdom

- ↑ History of Football

- 1 2 3 4 Royal Engineers A.F.C. at the Football Club History Database

- 1 2 When the Sappers won the FA Cup 1875 Royal Engineers Museum

- ↑ Antiques Trade Gazette 20 May 2013

- ↑ John Mullocks Auctions

- ↑ BBC News 6 September 2012

- ↑ History Section - Welfare and Sports

- ↑ Cunningham, Sam (7 November 2012). "Wanderers and Royal Engineers set for FA Cup final remake ... 140 years after original showdown". Daily Mail. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ↑ Al-Samarrai, Riath (7 November 2012). "Engineers steamroll Wanderers 7-1 in repeat of first ever FA Cup final at The Oval ... 140 years after the original". Daily Mail. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ↑ Army Players and International Representation (1871 onwards)

- ↑ Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol II. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ↑ "Royal Signals Heritage". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Aves, William A. T. (2009). The Railway Operating Division on the Western Front : the Royal Engineers in France and Belgium 1915-1919. Donington : Shaun Tyas. ISBN 978-1900289993.

- ↑ "Tommy's Mail & the Army Post Office". World War 1 postcards. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Royal Engineers". Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "History Section - Sappers VCs". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on 10 August 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ "Monument to the Royal Engineers at Arromanches Saint-Combe-de-Fresne France". Retrieved 30 January 2015.

Further reading

- British Garrison Berlin 1945–1994, "No where to go", W. Durie ISBN 978-3-86408-068-5

- Follow the Sapper: An Illustrated History of the Corps of Royal Engineers, by Colonel Gerald Napier RE. Published by The Institution of Royal Engineers, 2005. ISBN 0-903530-26-0.

- The History of the Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners: From the Formation of the Corps in March 1772, to the Date when Its Designation was Changed to that of Royal Engineers, in October 1856, by Thomas William John Connolly. Published by Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1857.

- History of the Corps of Royal Engineers, by Whitworth Porter, Charles Moore Watson. Published by Longmans, Green, 1889.

- The Royal Engineer, by Francis Bond Head. Published by John Murray, 1869.

- Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers, by Great Britain Army. Royal Engineers. Published by The Corps, 1874.

- Professional Papers of the Corps of Royal Engineers, by Great Britain Army. Royal Engineers, Royal Engineers' Institute (Great Britain). Published by Royal Engineer Institute, 1892.

- The Royal Engineers in Egypt and the Sudan, by Edward Warren Caulfeild Sandes. Published by Institution of Royal Engineers, 1937.

- Citizen Soldiers of the Royal Engineers Transportation and Movements and the Royal Army Service Corps, 1859 to 1965, by Gerard Williams, Michael Williams. Published by Institution of the Royal Corps of Transport, 1969.

- Royal Engineers, by Derek Boyd. Published by Cooper, 1975. ISBN 0-85052-197-1.

- The Royal Engineers, by Terry Gander. Published by I. Allan, 1985. ISBN 0-7110-1517-1.

- Versatile Genius: The Royal Engineers and Their Maps: Manuscript Maps and Plans of the Eastern Frontier, 1822–1870, by University of the Witwatersrand Library, Yvonne Garson. Published by University of the Witwatersrand Library, 1992. ISBN 1-86838-023-8.

- The History of the Royal Engineer Yacht Club, by Sir Gerald Duke. Published by Pitman Press, 1982. ISBN 0-946403-00-7.

- From Ballon to Boxkite. The Royal Engineers and Early British Aeronautics, by Malcolm Hall. Published by Amberley, 2010. ISBN 978-1-84868-992-3.

- A Harbour Goes to War. The story of the Mulberry and the men who made it happen, by Evans, J. Palmer, E & Walter, R. Published by Brook House, 2000. ISBN 1-873547-30-7.

- Danger UXB. The Heroic Story of the WWII Bomb Disposal Teams, by James Owen. Published by Little, Brown, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4087-0195-9.

- Designed to Kill. Bomb Disposal from World War I to the Falklands, by Major Arthur Hogben. Published by Patrick Stevens, 1987. ISBN 0-85059-865-6.

- UXB Malta. Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal 1940–44, by S A M Hudson. Published by The History Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7524-5635-5.

- The Underground War. Vimy Ridge to Arras, by Robinson, P & Cave, N. Published by Pen and Sword, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84415-976-5.

- XD Operations. Secret British Missions Denying Oil to the Nazis, by Brazier, C. C. H. Published by Pen and Sword, 2004. ISBN 1-84415-136-0.

- Blowing Our Bridges. A Memoir from Dunkirk to Korea via Normandy, by Maj Gen Tony Younger. Published by Pen and Sword, 2004. ISBN 1-84415-051-8.

- Code Name Mulberry. The Planning - Building & Operation of the Normandy Harbours, by Guy Hartcup. Published by Pen and Sword, 2006. ISBN 1-84415-434-3.

- Summon up the Blood. The war diary of Corporal J A Womack, Royal Engineers, by Celia Wolfe. Published by Leo Cooper, 1997. ISBN 978-0-85052-537-3.

- Fight, Dig and Live. The Story of the Royal Engineers in the Korean War, by George Cooper. Published by Pen and Sword, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84884-684-5.

- Stick & String, by Terence Tinsley. Published by Buckland Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0-7212-0897-5.

- Honourable Conquests. An account of the enduring works of the Royal Engineers throughout the Empire, by Smithers, A. J. Published by Leo Cooper, 1991. ISBN 0-85052-725-2.

- Never a Shot in Anger, by Gerald Mortimer. Published by Square One Publications, 1993. ISBN 1-872017-71-1.

- Platoon Commander (Memoirs of a Royal Engineers Officer), by Peter Steadman. Published by Pentlandite Books, 2001. ISBN 1-85821-901-9.

- Commander Royal Engineers. The Headquarters of the Royal Engineers at Arnhem, by John Sliz. Published by Travelouge 219, 2013. ISBN 978-1-927679-04-3.

- The Lonely War. A story of Bomb Disposal in World War II by on who was there, by Eric Wakeling. Published by Square One Publication, 1994. ISBN 1-872017-84-3.

- Bombs & Bobby Traps, by H. J. Hunt. Published by Romsey Medal Centre, 1986. ISBN 0-948251-19-0.

- With the Royal Engineers in the Peninsula & France, by Charles Boothby. Published by Leonaur, 2011. ISBN 978-0-85706-781-4.

- Inland Water Transport in Mesopotamia, by Lt Col L. J. Hall. Published by Naval & Military Press, 1919. ISBN 1-84342-952-7.

- A Short History of the Royal Engineers, by The Institution of Royal Engineers. Published by The Institution of Royal Engineers, 2006. ISBN 0-903530-28-7.

- Don't Annoy The Enemy, by Eric Walker. Published by Gernsey Press Co. ISBN Not on publication.

- Oh! To be a Sapper, by M. J. Salmon. Published by The Institution of Royal Engineers. ISBN 0-9524911-4-1.

- Middle East Movers, Royal Engineers Transportation in the Suez Canal Zone 1947–1956, Hugh Mackintosh. Published by North Kent Books, 2000. ISBN 0-948305-10-X.

- Mediterranean Safari March 1943 - October 1944, by A. P. de T. Daniell. Published by Orphans Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7212-0816-9.

- A Sapper's War, by Leonard Watkins. Published by Minerva Press, 1996. ISBN 1-85863-715-5.

- A Game of Soldiers by C. Richard Eke. Published by Digaprint Ltd, 1997. ISBN 0-9534264-0-8.

- Wrong Again Dan! Karachi to Krakatoa, by Dan Raschen RE. Published by Buckland Publications, 1983. ISBN 0-7212-0638-7.

- Send Port & Pyjamas!, by Dan Raschen RE. Published by Buckland Publications, 1987. ISBN 0-7212-0763-4.

- Highly Explosive, The Exploits of Major Bill Hartley MBE GM late of Bomb Disposal, by John Frayn Turner. Published by George G. Harappa & Co Ltd, 1967. ISBN Not on Publication.

- Sapper Martin, The Secret War Diary of Jack Martin, by Richard Van Emden. Published by Bloomsbury, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4088-0311-0.

- Drainage Manual - Revised Edition, 1907, by Locock and Tyndale.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Engineers. |

- Official Royal Engineers MOD Site

- Institution of Royal Engineers

- Royal Engineers – Continuous Professional Development

- Site for finding current and former serving members of the Corps

- 7 Fd Sqn Memories

- 29 Fld Sqn (vets) Association

- 60 HQ & Sp Sqn History

- Royal Engineers Association

- Royal Engineers Museum, Library and Archive

- Royal Engineers Band

- The Royal Engineers in Halifax: Photographing the Garrison City, 1870–1885

- The Columbia Detachment of the Royal Engineers, an online history and biographies of the Royal Engineers in colonial-era British Columbia

- Airborne Engineers Association

- Engineering Council UK

- Rochester Cathedral

- "History of 555 Field Company Royal Engineers in WW2"

- Royal Engineers Companies 1944 - 1945 at www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk