Chinese paper folding

Chinese paper folding, or zhezhi (Chinese: 摺紙; pinyin: zhézhǐ), is the art of paper folding that originated in China.

The work of Akira Yoshizawa widely popularized the Japanese name "origami"; however, in China and other Chinese speaking places, the art is referred to by the Chinese name, zhezhi. Traditional Chinese paper folding concentrates mainly on objects like boats or hats rather than the animals and flowers of Japanese origami. A recent innovation is Golden Venture where large representational objects are made from modular forms.

History

Paper was first invented by Cai Lun in the Eastern Han Dynasty in China. In the 6th century, Buddhist monks carried paper to Japan.[1] The earliest document showing paper folding is a picture of a small paper boat in an edition of Tractatus de sphaera mundi from 1490 by Johannes de Sacrobosco. However it is very likely that paper folding originated much earlier than that in China and Japan for ceremonial purposes. In China, traditional funerals include burning folded paper, most often representations of gold nuggets (yuanbao). This practice probably started when papers gradually become popular and cheaper in China, and it seems to have become quite common during the Sung Dynasty (905-1125 CE).[2] In Japan origami butterflies were used during the celebration of Shinto weddings to represent the bride and groom, so ceremonial paperfolding had probably already become a significant aspect of Japanese ceremony by the Heian period (794–1185) of Japanese history.[3]

It is possible that paper folding came to Japan from China when paper was introduced but there is no evidence for this.[4] The paper folding of China has typically been of objects like dishes, hats or boats rather than animals or flowers of Japan.[5] The Japanese treasure ship model is probably derived from the Chinese model which uses an unusual fold that may have been inspired by the folded sychee, however in general the models of the two countries are quite different.[6]

Significant early publications

Maying Soong's 1948 book, The Art of Chinese Paper Folding, helped popularise recreational paper folding in the 20th century, and was possibly the first to distinguish the difference between Chinese versus Japanese paper folding- where the Chinese focus primarily on inanimate objects, such as boats or pagoda, the Japanese include representations of living forms, such as the crane. It contains a number of simple traditional designs, some of which are also found in the traditions of other countries. A number of the models are folded from the blintz base, a form also common in traditional European and Japanese paper folding. The Old Scholar's Hat is among the old Chinese models found in this book. and the main quote of this book.

Tridimensional origami

In 1993, a group of Chinese refugees were detained on the ship Golden Venture and held in American prison, where they began making elaborate models combining traditional Chinese modular paperfolding (utilizing materials such as magazine covers) with a form of papier-mâché (using toilet tissue); these models were given to those aiding the refugees and sold at charity fund raisers. Media coverage of the refugees helped popularize traditional Chinese modular folding worldwide- which became known as 'Golden Venture folding'.[7]

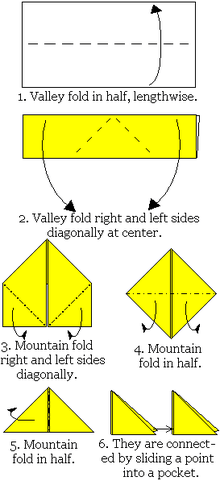

This type of modular folding is often done with Chinese paper money. Triangles are folded from multiple pieces of 1:2 aspect ratio paper, and connected by inserting a flap of one triangle into a pocket on the next. Popular subjects include pineapples, swans, and ships. This form of modular origami is commonly referred to as '3D origami'.

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Nick Robinson, The Origami Bible (2004), p. 10.

- ↑ Laing, Ellen Johnston (2004). Up In Flames. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3455-4.

- ↑ Raffaele Leonardi (1997). "A brief history of origami". Centro Diffusione Origami.

- ↑ David Lister. "Errors and misconceptions about the history of paperfolding". British Origami Society.

- ↑ Temko, Florence (1986). Paper Pandas and Jumping Frogs. p. 123. ISBN 0-8351-1770-7.

- ↑ Davis Lister. "Is the Junk Chinese?". British Origami Society.

- ↑ Origami-rs. "Origami-rs." Golden Venture Folding. Retrieved on 2007-05-24.

External links

- "Origami" at chine-culture.com. Retrieved October 9, 2016.