335th Bombardment Squadron

335th Bombardment Squadron

| |

|---|---|

|

Boeing B-52D Stratofortress as flown by the 335th Bomb Sq refueling from a KC-135A | |

| Active | 1942–1945; 1947–1949; 1952–1963 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Role | Bombardment |

| Part of | Strategic Air Command |

| Engagements | European Theater of World War II |

| Decorations | Distinguished Unit Citation |

| Insignia | |

| 335th Bombardment Squadron emblem (approved 20 April 1956)[1] |

|

| World War II Squadron fuselage code[2][3] | OE |

| World War II 95th group tail code[2] | Square B |

The 335th Bombardment Squadron is an inactive United States Air Force unit. It was last assigned to the 4130th Strategic Wing at Bergstrom Air Force Base, Texas on 15 September 1963.

The squadron was first activated in June 1942. It saw combat in the European Theater of World War II, where it was assigned to the 95th Bombardment Group, the only group in Eighth Air Force to earn three Distinguished Unit Citations.[4]

From 1947 to 1949 the 335th Bombardment Squadron served in the reserves. It was inactivated when Continental Air Command reorganized its reserve flying units under the wing base organization model.

During the Cold War, the squadron was part of Strategic Air Command (SAC)'s 95th Bombardment Wing and performed strategic bombardment training with Convair B-36 Peacemaker bombers at Biggs Air Force Base. Texas. In 1959, as part of SAC's program to disperse its Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bombers over a larger number of bases to make them less vulnerable to a Soviet missile attack, the squadron moved to Bergstrom Air Force Base, where it operated the B-52. It supported SAC's global commitments until 1963, when SAC replaced its strategic wings and their components with wings that continued the histories of units that had participated in combat in World War II.

History

World War II

Training in the United States

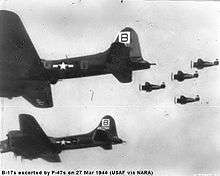

The squadron was constituted in early 1942 as the 335th Bombardment Squadron before activating at Barksdale Field, Louisiana in June as one of the four original squadrons of the 95th Bombardment Group.[1][5] The squadron began training in August at Geiger Field, Washington,[4] where it was equipped with Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses. The unit trained for combat operations until moving overseas starting in March.[5]

The air echelon processed at Kearney Army Air Field, Nebraska and flew its Forts via the southern route, flying to Florida, Trinidad, the northern coast of Brazil, Dakar, Senegal, and Marrakesh, Morocco to RAF Alconbury in the United Kingdom. The ground echelon moved to Camp Kilmer, then sailed on the RMS Queen Elizabeth to Scotland, arriving in May. The squadron then reunited at RAF Framlingham.[4]

Combat with Eighth Air Force

The squadron arrived in England equipped with late model B-17F aircraft equipped with "Tokyo Tanks", additional fuel cells located outboard in the wings that gave this model additional range.[6] It flew its first combat mission on 13 May 1943 against an airfield near Saint-Omer, France. For the next two months the squadron focused on attacking airfields and V-1 flying bomb launch sites in France.[5]

Eighth Air Force's early experience with its Martin B-26 Marauders convinced it that the Marauders were stationed too far from the continent of Europe to reach a selection of targets.[7] It determined to move them closer to the target areas, and an exchange of bases began. The entire 95th group moved to RAF Horham in June, where they replaced the 323d Bombardment Group, which departed the previous day.[5][8] A few days later their place at Framlingham was taken by the newly arrived 390th Bombardment Group.[5][9]

The 335th began strategic bombing operations in July and continued until flying its last operation on 20 April 1945. Its targets included harbors, marshalling yards and other industrial targets along with attacks on cities. The squadron received its first Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC) during an attack on an aircraft factory at Regensburg, Germany on 17 August 1943 when it maintained its defensive formation despite severe attacks by enemy interceptor aircraft.[5]

On 10 October, during an attack on marshalling yards at Münster, Germany, the squadron was subjected to concentrated fighter attacks on the approach to the target and intense flak over the objective.[5] Despite these obstacles, the formation's bombs were clustered close to the target.[10] It was awarded a second DUC for withstanding these attacks to bomb its objective. From 20 to 25 February 1944 the squadron participated in the Big Week offensive against the German aircraft manufacturing industry. A few days later, on 4 March, the squadron attacked Berlin despite adverse weather that led other units to either abandon the operation or attack secondary targets. Despite snowstorms and heavy cloud cover, the unit struck its target while under attack from enemy fighters,[5] although the cloud cover required the group to rely on a pathfinder from the 482d Bombardment Group to determine the release point.[11] It received its third DUC for this operation.[5] This mission was the first time any unit from Eighth Air Force had bombed Berlin.[4]

The squadron was diverted to bombing priority tactical targets during the preparation for and execution of Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy in June 1944, attacking communications and coastal defenses. It hit enemy troop concentrations to facilitate the Allied breakout at Saint-Lô. The 335th attacked enemy troop concentrations during the Battle of the Bulge from December 1944 to January 1945 and bombed airfields to support Operation Varsity, the airborne assault across the Rhine in March.[5]

One of the unit's more unusual missions was flown on 18 September 1944, when the 95th group led the 13th Combat Bombardment Wing[12] to Warsaw to drop ammunition, food and medical supplies to Polish resistance forces fighting against German occupation forces,[5] landing at bases in the Soviet Union. The squadron had previously participated in shuttle missions to the Soviet Union.[13]

The unit flew its last mission on 20 April 1945, when it attacked marshalling yards near Oranienburg. In the first week of May, it airdropped food to Dutch citizens in Operation Chow Hound. From V-E Day until departing the theater in June, it transported liberated prisoners of war and displaced persons.[5][14] The air echelon flew their planes back to Bradley Field, Connecticut, while the ground echelon sailed once more on the Queen Elizabeth.[4] The squadron was reunited at Sioux Falls Army Air Field, South Dakota, where it was inactivated on 28 August 1945.[5]

Cold War

Air Force Reserve

The 335th Bombardment Squadron was reactivated as a reserve unit under Air Defense Command (ADC) at Memphis International Airport, Tennessee in May 1947 as a Boeing B-29 Superfortress unit. At Memphis its training was supervised by the 468th AAF Base Unit (later the 2584th Air Force Reserve Training Center).[15] It is not clear whether or not the squadron was fully staffed or equipped. In 1948 Continental Air Command assumed responsibility for managing reserve units from ADC.[16] The 335th was inactivated when Continental Air Command reorganized its reserve units under the wing base organization system in June 1949.[5] The squadron's personnel and equipment were transferred to elements of the 516th Troop Carrier Wing.[15]

Strategic Air Command

.jpg)

The squadron activated on 16 June 1952 at Biggs Air Force Base, Texas. However it was minimally manned until September 1953, when it began strategic bombardment training with Convair B-36 Peacemakers.[17] It operated in support of Strategic Air Command (SAC)'s global commitments beginning in April 1954. The squadron deployed with the entire 95th Bombardment Wing to Andersen Air Force Base, Guam from July to November 1955.[17]

From 1959 to 1960, the 95th wing phased out its B-36 and received Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses to replace them. In the late 1950s, SAC established strategic wings to disperse its B-52s over a larger number of bases, thus making it more difficult for the Soviet Union to knock out the entire fleet with a surprise first strike.[18] As part of this program, the squadron moved to Bergstrom Air Force Base, Texas on 15 January 1959, where it was assigned to the 4130th Strategic Wing.[1]

Starting in 1960, one third of the squadron's aircraft were maintained on fifteen-minute alert, fully fueled, armed and ready for combat to reduce vulnerability to a Soviet missile strike. This was increased to half the squadron's aircraft in 1962.[19] The 335th continued to maintain an alert commitment until it was inactivated.[1]

In February 1963, The 340th Bombardment Wing moved on paper from Whiteman Air Force Base. Missouri and assumed the aircraft, personnel and equipment of the discontinued 4130th wing.[20] The 4130th was a Major Command controlled (MAJCON) wing, which could not carry a permanent history or lineage,[21] and SAC wanted to replace it with a permanent unit. The 335th was inactivated and its mission, personnel and equipment were transferred to the 340th wing's 486th Bombardment Squadron.[22]

Lineage

- Constituted as the 335th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy) on 28 January 1942

- Activated on 15 Jun 1942

- Redesignated 335th Bombardment Squadron, Heavy on 20 August 1943

- Inactivated on 28 August 1945

- Redesignated 335th Bombardment Squadron, Very Heavy on 13 May 1947

- Activated in the reserve on 29 May 1947

- Inactivated on 27 June 1949

- Redesignated 335th Bombardment Squadron, Medium on 4 June 1952

- Activated on 16 June 1952

- Redesignated 335th Bombardment Squadron, Heavy on 8 November 1952[23]

- Discontinued and inactivated on 1 September 1963[24]

Assignments

- 95th Bombardment Group, 15 June 1942 – 28 August 1945

- 95th Bombardment Group, 29 May 1947 – 27 June 1949

- 95th Bombardment Wing, 16 June 1952

- 4130th Strategic Wing, 15 January 1959[23] – 1 September 1963[24]

Stations

|

|

Aircraft

- Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, 1942–1945

- Convair B-36 Peacemaker, 1953–1959

- Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, 1959[23]–1963[24]

Awards and campaigns

| Award streamer | Award | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distinguished Unit Citation, Regensburg, Germany | 17 August 1943 | [1] | |

| Distinguished Unit Citation, Münster, Germany | 10 October 1943 | [1] | |

| Distinguished Unit Citation, Berlin, Germany | 4 March 1944 | [1] |

| Campaign Streamer | Campaign | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Offensive, Europe | 11 May 1943 – 5 June 1944 | [1] | |

| Normandy | 6 June 1944 – 24 July 1944 | [1] | |

| Northern France | 25 July 1944 – 14 September 1944 | [1] | |

| Rhineland | 15 September 1944 – 21 March 1945 | [1] | |

| Ardennes-Alsace | 16 December 1944 – 25 January 1945 | [1] | |

| Central Europe | 22 March 1944 – 21 May 1945 | [1] | |

| Air Combat, EAME Theater | 11 May 1943 – 11 May 1945 | [1] |

See also

- B-17 Flying Fortress units of the United States Army Air Forces

- List of B-52 Units of the United States Air Force

- List of MAJCOM wings of the United States Air Force

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. pp. 413–414. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556.

- 1 2 Watkins, Robert (2008). Battle Colors: Insignia and Markings of the Eighth Air Force In World War II. Vol I (VIII) Bomber Command. Atglen, PA: Shiffer Publishing Ltd. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0-7643-1987-6.

- ↑ After December 1944, squadrons of the 95th Bombardment Group no longer displayed their fuselage codes. Watkins, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Freeman, Roger A. (1970). The Mighty Eighth: Units, Men and Machines (A History of the US 8th Army Air Force). London, England, UK: Macdonald and Company. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-87938-638-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1983) [1961]. Air Force Combat Units of World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. pp. 163–165. ISBN 0-912799-02-1. LCCN 61060979.

- ↑ Freeman, p. 47

- ↑ Freeman, p. 50

- ↑ Maurer, Combat Units, pp. 203–204

- ↑ Maurer, Combat Units, pp. 277–278

- ↑ Freeman, p. 77

- ↑ Freeman, p. 113

- ↑ Freeman, pp. 175–176

- ↑ Freeman, p. 174

- ↑ Freeman, p. 230

- 1 2 See Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). Air Force Combat Wings, Lineage & Honors Histories 1947–1977 (PDF). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. pp. 283–284. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- ↑ "Abstract, Mission Project Closeup, Continental Air Command". Air Force History Index. 27 December 1961. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- 1 2 Ravenstein, Combat Wings, pp. 133–134

- ↑ "Abstract (Unclassified), Vol 1, History of Strategic Air Command, Jan–Jun 1957 (Secret)". Air Force History Index. 23 August 1985. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ↑ "Abstract (Unclassified), History of the Strategic Bomber since 1945 (Top Secret, downgraded to Secret)". Air Force History Index. 1 April 1975. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Ravenstein, Combat Wings, pp. 179–180

- ↑ Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). A Guide to Air Force Lineage and Honors (2d, Revised ed.). Maxwell AFB, AL: USAF Historical Research Center. p. 12.

- ↑ See Ravenstein, Combat Wings, pp. 179–180

- 1 2 3 4 Lineage, including assignments, stations and aircraft through 1962 in Maurer, Combat Squadrons, pp. 414–415

- 1 2 3 4 "Abstract, History 340 Bombardment Wing". Air Force History Index. 22 February 1990 [First published 1 September 1963]. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- 1 2 Station number in Anderson, Capt. Barry (1985). Army Air Forces Stations: A Guide to the Stations Where U.S. Army Air Forces Personnel Served in the United Kingdom During World War II (PDF). Maxwell AFB, AL: Research Division, USAF Historical Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

Bibliography

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

- Anderson, Capt. Barry (1985). Army Air Forces Stations: A Guide to the Stations Where U.S. Army Air Forces Personnel Served in the United Kingdom During World War II (PDF). Maxwell AFB, AL: Research Division, USAF Historical Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Freeman, Roger A. (1970). The Mighty Eighth: Units, Men and Machines (A History of the US 8th Army Air Force). London, England, UK: Macdonald and Company. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-87938-638-2.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1983) [1961]. Air Force Combat Units of World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. pp. 163–165. ISBN 0-912799-02-1. LCCN 61060979.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556.

- Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). Air Force Combat Wings, Lineage & Honors Histories 1947–1977 (PDF). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). A Guide to Air Force Lineage and Honors (2d, Revised ed.). Maxwell AFB, AL: USAF Historical Research Center.

- Watkins, Robert (2008). Battle Colors: Insignia and Markings of the Eighth Air Force In World War II. Vol I (VIII) Bomber Command. Atglen, PA: Shiffer Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7643-1987-6.

Further reading

- Andrews, Paul M. (1990). Operational Record of the 95th Bomb Group World War II. Bellevue, WA: 95th Bomb Group (H) Association.

- Cantwell, Gerald T. (1997). Citizen Airmen: a History of the Air Force Reserve, 1946–1994. Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program. ISBN 0-16049-269-6.

- Dwyer, John P., ed. (1945). The 95th Bombardment Group H, United States Army Air Forces. Cincinnati, OH: A.H. Pugh Printing Co.

- Hawkins, Dan (1990). B-17s Over Berlin: Personal Stories from the 95th Bomb Group (H). Washington, DC: Brassey's (U.S.).

- Hawkins, Dan (1987). Courage, Honor, Victory: A First Person History of the 95th Bomb Group (H). Bellevue, WA: 95th Bomb Group (H) Association.

- Yenne, Bill (2012). B-52 Stratofortress: The complete history of history's longest serving and best known bomber. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-4302-9. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

External links

- "95th Bomb Group (H) Memorials Foundation". 95thbg.org. 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- "95th B.G. Horham Heritage Association". 95th Bomb Group Heritage Association. 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- Broyhill, Marvin T. (2003). "95th Bombardment Wing, 95th Strategic Wing, 95th Air Base Wing". Strategic-Air-Command.com. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

_is_refueled_by_Boeing_KC-135A-BN_(SN_55-3127)_061127-F-1234S-009.jpg)

.svg.png)