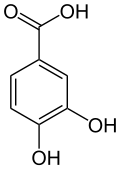

Protocatechuic acid

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | |

| Other names

3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid PCA Protocatechuate | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.509 |

| EC Number | 202-760-0 |

| PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number | UL0560000 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C7H6O4 | |

| Molar mass | 154.12 g/mol |

| Appearance | light brown solid |

| Density | 1.54 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 221 °C (430 °F; 494 K) (decomposes) |

| 1.24 g/100 mL | |

| Solubility | soluble in ethanol, ether insoluble in benzene |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.48 [1] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | MSDS |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Protocatechuic acid (PCA) is a dihydroxybenzoic acid, a type of phenolic acid. It is a major metabolite of antioxidant polyphenols found in green tea. It has mixed effects on normal and cancer cells in in vitro and in vivo studies.[2]

Biological effects

Protocatechuic acid (PCA) is antioxidant and anti-inflammatory. PCA extracted from Hibiscus sabdariffa protected against chemically induced liver toxicity in vivo. In vitro testing documented antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of PCA, while liver protection in vivo was measured by chemical markers and histological assessment.[3]

PCA has been reported to induce apoptosis of human leukemia cells, as well as malignant HSG1 cells taken from human oral cavities,[4] but PCA was found to have mixed effects on TPA-induced mouse skin tumours. Depending on the amount of PCA and the time before application, PCA could reduce or enhance tumour growth.[5] Similarly, PCA was reported to increase proliferation and inhibit apoptosis of neural stem cells.[6] In an in vitro model using HL-60leukemia cells, protocatechuic acid showed an antigenotoxic effect and tumoricidal activity.[7]

Occurrence in nature

Protocatechuic acid can be isolated from the stem bark of Boswellia dalzielii.[8] and from leaves of Diospyros melanoxylon [9]

The hardening of the protein component of insect cuticle has been shown to be due to the tanning action of an agent produced by oxidation of a phenolic substance. In the analogous hardening of the cockroach ootheca, the phenolic substance concerned is protocatechuic acid.[10]

In foods

Açaí oil, obtained from the fruit of the açaí palm (Euterpe oleracea), is rich in protocatechuic acid (630 ± 36 mg/kg).,[11] Protocatechuic acid also exists in the skins of some strains of onion as an antifungal mechanism, increasing endogenous resistance against smudge fungus. It is also found in Allium cepa (17,540 ppm).[12]

PCA occurs in roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa), which is used worldwide as a food and beverage.[3]

Protocatechuic acid is also found in mushrooms such as Agaricus bisporus[13] or Phellinus linteus.[14]

Metabolism

Protocatechuic acid is one of the main catechins metabolites found in humans after consumption of green tea infusions.[15]

Enzymes

- Biosynthesis enzymes

- 3-dehydroshikimate dehydratase

- (3S,4R)-3,4-dihydroxycyclohexa-1,5-diene-1,4-dicarboxylate dehydrogenase

- Terephthalate 1,2-cis-dihydrodiol dehydrogenase

- 3-hydroxybenzoate 4-monooxygenase

- 4-hydroxybenzoate 3-monooxygenase (NAD(P)H)

- 4-sulfobenzoate 3,4-dioxygenase

- Vanillate monooxygenase

- 3,4-dihydroxyphthalate decarboxylase

- 4,5-dihydroxyphthalate decarboxylase

- Degradation enzymes

The enzyme protocatechuate decarboxylase uses 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate to produce catechol and CO2.

The enzyme protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase uses 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate and O2 to produce 3-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate.

See also

References

- ↑ Dawson, R. M. C. et al., Data for Biochemical Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1959.

- ↑ Lin HH, Chen JH, Huang CC, Wang CJ (June 2007). "Apoptotic effect of 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid on human gastric carcinoma cells involving JNK/p38 MAPK signaling activation.". Int J Cancer. 120 (11): 2306–2316. PMID 17304508. doi:10.1002/ijc.22571.

- 1 2 Liu, CL; Wang, JM; Chu, CY; Cheng, MT; Tseng, TH (2002). "In vivo protective effect of protocatechuic acid on tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced rat hepatotoxicity". Food Chem Toxicol. 40 (5): 635–41. PMID 11955669. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00002-9.

- ↑ Babich H, Sedletcaia A, Kenigsberg B (November 2002). "In vitro cytotoxicity of protocatechuic acid to cultured human cells from oral tissue: involvement in oxidative stress". Pharmacol. Toxicol. 91 (5): 245–253. PMID 12570031. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.910505.x.

- ↑ Nakamura Y, Torikai K, Ohto Y, Murakami A, Tanaka T, Ohigashi H (October 2000). "A simple phenolic antioxidant protocatechuic acid enhances tumor promotion and oxidative stress in female ICR mouse skin: dose-and timing-dependent enhancement and involvement of bioactivation by tyrosinase". Carcinogenesis. 21 (10): 1899–1907. PMID 11023549. doi:10.1093/carcin/21.10.1899.

- ↑ Guan S, Ge D, Liu TQ, Ma XH, Cui ZF (March 2009). "Protocatechuic acid promotes cell proliferation and reduces basal apoptosis in cultured neural stem cells". Toxicology in Vitro. 23 (2): 201–208. PMID 19095056. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2008.11.008.

- ↑ Anter J, Romero-Jiménez M, Fernández-Bedmar Z, Villatoro-Pulido M, Analla M, Alonso-Moraga A, Muñoz-Serrano A.,"Antigenotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and apoptosis induction by apigenin, bisabolol, and protocatechuic acid." J Med Food. 2011 Mar;14(3):276-83

- ↑ Antibacterial phenolics from Boswellia dalzielii. Alemika Taiwo E, Onawunmi Grace O and Olugbade, Tiwalade O, Nigerian Journal of Natural Products and Medicines, 2006 (abstract)

- ↑ Mallavadhani UV, Mahapatra A. A new aurone and two rare metabolites from the leaves of Diospyros melanoxylon. Nat Prod Res 2005; 19:91-97

- ↑ Hackman, R. H.; Pryor, M. G.; Todd, A. R. (1948). "The occurrence of phenolic substances in arthropods". The Biochemical Journal. 43 (3): 474–477. PMC 1274717

. PMID 16748434. doi:10.1042/bj0430474.

. PMID 16748434. doi:10.1042/bj0430474. - ↑ Pacheco-Palencia LA, Mertens-Talcott S, Talcott ST (Jun 2008). "Chemical composition, antioxidant properties, and thermal stability of a phytochemical enriched oil from Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.)". J Agric Food Chem. 56 (12): 4631–6. PMID 18522407. doi:10.1021/jf800161u.

- ↑ http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/duke/highchem.pl

- ↑ Delsignore, A; Romeo, F; Giaccio, M (1997). "Content of phenolic substances in basidiomycetes". Mycological Research. 101 (5): 552–6. doi:10.1017/S0953756296003206.

- ↑ Lee YS, Kang YH, Jung JY, et al. (October 2008). "Protein glycation inhibitors from the fruiting body of Phellinus linteus". Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 31 (10): 1968–72. PMID 18827365. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.1968. Archived from the original on 2012-12-19.

- ↑ Pietta, P. G.; Simonetti, P.; Gardana, C.; Brusamolino, A.; Morazzoni, P.; Bombardelli, E. (1998). "Catechin metabolites after intake of green tea infusions". BioFactors. 8 (1-2): 111–118. PMID 9699018. doi:10.1002/biof.5520080119.