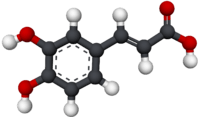

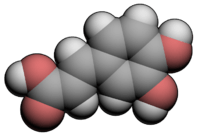

Caffeic acid

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-2-propenoic acid 3,4-Dihydroxy-cinnamic acid trans-Caffeate 3,4-Dihydroxy-trans-cinnamate (E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-2-propenoic acid 3,4-Dihydroxybenzeneacrylicacid 3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-2-propenoic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.784 |

| KEGG | |

| PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H8O4 | |

| Molar mass | 180.16 g/mol |

| Density | 1.478 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 223 to 225 °C (433 to 437 °F; 496 to 498 K) |

| UV-vis (λmax) | 327 nm and a shoulder at c. 295 nm in acidified methanol[1] |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Chlorogenic acid Cichoric acid Coumaric acid Quinic acid |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Caffeic acid is an organic compound that is classified as a hydroxycinnamic acid. This yellow solid consists of both phenolic and acrylic functional groups. It is found in all plants because it is a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of lignin, one of the principal components of plant biomass and its residues.[2]

Natural occurrences

Caffeic acid can be found in the bark of Eucalyptus globulus.[3] It can also be found in the freshwater fern Salvinia molesta[4] or in the mushroom Phellinus linteus.[5]

Occurrences in food

Caffeic acid is found at a very modest level in coffee, at 0.03 mg per 100 ml.[6] It is one of the main natural phenols in argan oil.[7]

It is found at a high level in some herbs, especially thyme, sage and spearmint (at about 20 mg per 100 g), at high levels in spices, especially Ceylon cinnamon and star anise (at about 22 mg per 100 g), found at fairly high level in sunflower seeds (8 mg per 100 g), and at modest levels in red wine (1.88 mg per 100 ml) and in apple sauce, apricots and prunes (at about 1 mg per 100 g). It is at a super high level in black chokeberry (141 mg per 100 g) and in fairly high level in lingonberry (6 mg per 100 g).[6] It is also quite high in the South American herb yerba mate (150 mg per 100 g based on thin layer chromatography densiometry [8] and HPLC [9]).

It is also found in barley grain,[10] and in rye grain.[6]

Metabolism

Biosynthesis

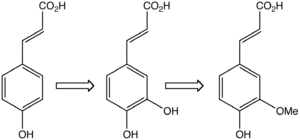

Caffeic acid, which is unrelated to caffeine, is biosynthesized by hydroxylation of coumaroyl ester of quinic acid (esterified through a side chain alcohol). This hydroxylation produces the caffeic acid ester of shikimic acid, which converts to chlorogenic acid. It is the precursor to ferulic acid, coniferyl alcohol, and sinapyl alcohol, all of which are significant building blocks in lignin.[2] The transformation to ferulic acid is catalyzed by the enzyme caffeate O-methyltransferase.

Caffeic acid and its derivative caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) are produced in many kinds of plants.[11][12][13]

In plants, caffeic acid (middle) is formed from 4-hydroxycinnamic acid (left) and is transformed to ferulic acid.

In plants, caffeic acid (middle) is formed from 4-hydroxycinnamic acid (left) and is transformed to ferulic acid.

Dihydroxyphenylalanine ammonia-lyase was presumed to use 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (L-DOPA) to produce trans-caffeate and NH3. However, the EC number for this purported enzyme was deleted in 2007, as no evidence has emerged for its existence.[14]

Biotransformation

Caffeate O-methyltransferase is an enzyme responsible for the transformation of caffeic acid into ferulic acid.

Caffeic acid and related o-diphenols are rapidly oxidized by o-diphenol oxidases in tissue extracts.[15]

Biodegradation

Caffeate 3,4-dioxygenase is an enzyme that uses caffeic acid and oxygen to produce 3-(2-carboxyethenyl)-cis,cis-muconate.

Glysosides

3-O-caffeoylshikimic acid (dactylifric acid) and its isomers, are enzymic browning substrates found in dates (Phoenix dactylifera fruits).[16]

Pharmacology

Caffeic acid has a variety of potential pharmacological effects in in vitro studies and in animal models, and the inhibitory effect of caffeic acid on cancer cell proliferation by an oxidative mechanism in the human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cell line has recently been established.[17]

Caffeic acid is an antioxidant in vitro and also in vivo.[13] Caffeic acid also shows immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activity. Caffeic acid outperformed the other antioxidants, reducing aflatoxin production by more than 95 percent. The studies are the first to show that oxidative stress that would otherwise trigger or enhance Aspergillus flavus aflatoxin production can be stymied by caffeic acid. This opens the door to use as a natural fungicide by supplementing trees with antioxidants.[18]

Studies of the carcinogenicity of caffeic acid have mixed results. Some studies have shown that it inhibits carcinogenesis, and other experiments show carcinogenic effects.[19] Oral administration of high doses of caffeic acid in rats has caused stomach papillomas.[19] In the same study, high doses of combined antioxidants, including caffeic acid, showed a significant decrease in growth of colon tumors in those same rats. No significant effect was noted otherwise. Caffeic acid is listed under some Hazard Data sheets as a potential carcinogen,[20] as has been listed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a Group 2B carcinogen ("possibly carcinogenic to humans").[21] More recent data show that bacteria in the rats' guts may alter the formation of metabolites of caffeic acid.[22][23] Other than caffeic acid being a thiamine antagonist (antithiamine factor), there have been no known ill effects of caffeic acid in humans.

Chemistry

Caffeic acid is susceptible to autoxidation. Glutathione and thiol compounds (cysteine, thioglycolic acid or thiocresol) or ascorbic acid have a protective effect on browning and disappearance of caffeic acid.[24] This browning is due to the conversion of o-diphenols into reactive o-quinones. Chemical oxidation of caffeic acid in acidic conditions using sodium periodate leads to the formation of dimers with a furan structure (isomers of 2,5-(3′,4′-dihydroxyphenyl)tetrahydrofuran 3,4-dicarboxylic acid).[25] Caffeic acid can also be polymerized using the horseradish peroxidase/H2O2 oxidizing system.[26]

Other uses

Caffeic acid may be the active ingredient in caffenol, a do-it-yourself black-and-white photographic developer made from instant coffee.[27] The developing chemistry is similar to that of catechol or pyrogallol.[28]

It is also used as a matrix in MALDI mass spectrometry analyses.[29]

Isomers

Isomers with the same molecular formula and in the hydroxycinammic acids family are:

- Umbellic acid (2,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid)

- 2,3-Dihydroxycinnamic acid

- 2,5-Dihydroxycinnamic acid

References

- ↑ Gould, Kevin S.; Markham, Kenneth R.; Smith, Richard H.; Goris, Jessica J. (2000). "Functional role of anthocyanins in the leaves of Quintinia serrata A. Cunn.". Journal of Experimental Botany. 51 (347): 1107–1115. PMID 10948238. doi:10.1093/jexbot/51.347.1107.

- 1 2 Boerjan, Wout; Ralph, John; Baucher, Marie (2003). "Ligninbiosynthesis". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 54: 519–546. PMID 14503002. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938.

- ↑ Santos, Sónia A. O.; Freire, Carmen S. R.; Domingues, M. Rosário M.; Silvestre, Armando J. D.; Pascoal Neto, Carlos (2011). "Characterization of Phenolic Components in Polar Extracts of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. Bark by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 59 (17): 9386–9393. PMID 21761864. doi:10.1021/jf201801q.

- ↑ Choudhary, M. Iqbal; Naheed, Nadra; Abbaskhan, Ahmed; Musharraf, Syed Ghulam; Siddiqui, Hina; Atta-Ur-Rahman (2008). "Phenolic and other constituents of fresh water fern Salvinia molesta". Phytochemistry. 69 (4): 1018–1023. PMID 18177906. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.10.028.

- ↑ Lee, Y.-S.; Kang, Y.-H.; Jung, J.-Y.; Lee, Sanghyun; Ohuchi, Kazuo; Shin, Kuk Hyun; Kang, Il-Jun; Park, Jung Han Yoon; Shin, Hyun-Kyung; Soon, Sung (October 2008). "Protein glycation inhibitors from the fruiting body of Phellinus linteus". Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 31 (10): 1968–1972. PMID 18827365. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.1968. Archived from the original on 2012-12-19.

- 1 2 3 http://phenol-explorer.eu/contents/polyphenol/457

- ↑ Charrouf, Z.; Guillaume, D. (2007). "Phenols and Polyphenols from Argania spinosa". American Journal of Food Technology. 2 (7): 679–683. doi:10.3923/ajft.2007.679.683.

- ↑ http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jamc/2013/658596/

- ↑ http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/jf2008343

- ↑ Quinde-Axtell, Zory; Baik, Byung-Kee (2006). "Phenolic Compounds of Barley Grain and Their Implication in Food Product Discoloration". J. Agric. Food Chem. 54 (26): 9978–9984. PMID 17177530. doi:10.1021/jf060974w.

- ↑ Red Clover Flowers Herbal Information

- ↑ "Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases".

- 1 2 Olthof, M. R.; Hollman, P. C.; Katan, M. B. (January 2001). "Chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid are absorbed in humans". J. Nutr. 131 (1): 66–71. PMID 11208940.

- ↑

- ↑ Pierpoint, W. S. (1969). "o-Quinones formed in plant extracts. Their reactions with amino acids and peptides". Biochem. J. 112: 609–616. doi:10.1042/bj1120609.

- ↑ Maier, V. P.; Metzler, D. M.; Huber, A. F. (1964). "3-O-Caffeoylshikimic acid (dactylifric acid) and its isomers, a new class of enzymic browning substrates". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 14: 124–128. PMID 5836492. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(64)90241-4.

- ↑ Rajendra Prasad, N.; Karthikeyan, A.; Karthikeyan, S.; Reddy, B. V. (Mar 2011). "Inhibitory effect of caffeic acid on cancer cell proliferation by oxidative mechanism in human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cell line". Mol Cell Biochem. 349 (1–2): 11–19. doi:10.1007/s11010-010-0655-7.

- ↑ "Nuts’ New Aflatoxin Fighter: Caffeic Acid?".

- 1 2 Hirose, M.; Takesada, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Tamano, S.; Kato, T.; Shirai, T. (1998). "Carcinogenicity of antioxidants BHA, caffeic acid, sesamol, 4-methoxyphenol and catechol at low doses, either alone or in combination, and modulation of their effects in a rat medium-term multi-organ carcinogenesis model" (PDF). Carcinogenesis. 19 (1): 207–212. PMID 9472713. doi:10.1093/carcin/19.1.207.

- ↑ "Caffeic Acid". IARC Summary & Evaluation. 1993.

- ↑ Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, International Agency for Research on Cancer

- ↑ Peppercorn, M. A.; Goldman, P. (1972). "Caffeic acid metabolism by gnotobiotic rats and their intestinal bacteria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 69 (6): 1413–1415. PMC 426714

. PMID 4504351. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.6.1413.

. PMID 4504351. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.6.1413. - ↑ Gonthier, M.-P.; Verny, M.-A.; Besson, C.; Rémésy, C.; Scalbert, A. (1 June 2003). "Chlorogenic acid bioavailability largely depends on its metabolism by the gut microflora in rats". Journal of Nutrition. 133 (6): 1853–1859. PMID 12771329.

- ↑ Cilliers, Johannes J. L.; Singleton, Vernon L. (1990). "Caffeic acid autoxidation and the effects of thiols". J. Agric. Food Chem. 38 (9): 1789–1796. doi:10.1021/jf00099a002.

- ↑ Fulcrand, Hélène; Cheminat, Annie; Brouillard, Raymond; Cheynier, Véronique (1994). "Characterization of compounds obtained by chemical oxidation of caffeic acid in acidic conditions". Phytochemistry. 35 (2): 499–505. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94790-3.

- ↑ Xu, Peng; Uyama, Hiroshi; Whitten, James E.; Kobayashi, Shiro; Kaplan, David L. (2005). "Peroxidase-Catalyzed in Situ Polymerization of Surface Orientated Caffeic Acid". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (33): 11745–11753. PMID 16104752. doi:10.1021/ja051637r.

- ↑ "Caffenol-C-M, recipe". Caffenol blog.

- ↑ Williams, Scott. "A Use for that Last Cup of Coffee: Film and Paper Development". Technical Photographic Chemistry 1995 Class. Imaging and Photographic Technology Department, School of Photographic Arts and Sciences, Rochester Institute of Technology.

- ↑ Beavis, R. C.; Chait, B. T. (Dec 1989). "Cinnamic acid derivatives as matrices for ultraviolet laser desorption mass spectrometry of proteins". Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 3 (12): 432–435. PMID 2520223. doi:10.1002/rcm.1290031207.

External links

- "Chemical Land". Caffeic Acid as Carbocyclic Carboxylic Acid.