34th Infantry Division (United States)

| 34th Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

|

34th Infantry Division shoulder sleeve insignia | |

| Active |

1917–1963 1991–present |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Rosemount, MN |

| Nickname(s) |

"Red Bull" "The Sandstorm Division" |

| Motto(s) | "Attack, Attack, Attack!" |

| March |

"March of the Red Bull Legions" |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Brig. Gen. Jon Jensen[1] |

| Notable commanders |

Charles W. Ryder Charles L. Bolte Richard C. Nash |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia |

|

The 34th Infantry Division is an infantry division of the United States Army, part of the National Guard, that participated in World War I, World War II and multiple current conflicts. It was the first American division deployed to Europe in World War II, where it fought with great distinction in the Italian Campaign.[2]

The division was deactivated in 1945, and the 47th "Viking" Infantry Division later created in the division's former area. In 1991 the 47th Division was redesignated the 34th. Since 2001 division soldiers have served on homeland security duties in the continental United States, in Afghanistan, and in Iraq. The 34th has also been deployed to support peacekeeping efforts in the former Yugoslavia and elsewhere.[3]

The division continues to serve today, with most of the division part of the Minnesota and Iowa National Guard. In 2011, it was staffed by roughly 6,500 soldiers from the Minnesota National Guard,[4] 2,900 from the Iowa National Guard, about 300 from the Nebraska National Guard, and about 100 from other states.[5]

World War I

The division was established as the 34th of the National Guard in August 1917, consisting of units from North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota. On 25 August 1917, it was placed under the command of Maj. Gen. Augustus P. Blocksom,[6] who was succeeded by Brig. Gen. Frank G. Mauldin briefly on 18 September 1917 but was back in command by 10 December 1917.[7]

The division initially included the 67th Infantry Brigade, formed in August 1917 in the Iowa and Nebraska National Guards[8] and the 68th Infantry Brigade. The 67th Brigade comprised the 133rd Infantry Regiment and the 134th Infantry Regiment. The 68th Brigade comprised the 135th Infantry Regiment and the 136th Infantry Regiment.

The division takes its name from the shoulder sleeve insignia designed for a 1917 training camp contest by American regionalist artist Marvin Cone, who was then a soldier enlisted in the unit.[9] Cone's design evoked the desert training grounds of Camp Cody, New Mexico, by superimposing a red steer skull over a black Mexican water jug called an "olla." In World War I, the unit was called the "Sandstorm Division." German troops in World War II, however, called the U.S. division's soldiers "Red Devils" and "Red Bulls," the division later officially adopted the divisional nickname Red Bulls.[10]

Brig. Gen. Frank G. Mauldin took command.[11] The 34th Division arrived in France in October 1918 but it was too late for the division to be sent to the front, as the end of hostilities was near, an armistice being signed the following month.

Brig. Gen. John A. Johnston took command 26 October 1918, and some personnel were sent to other units to support their final operations. The 34th returned to the U.S. and was inactivated in December 1918.[12]

The 67th Infantry Brigade was disbanded in February 1919, but formed again in 1921, still as part of the 34th Division.

Between the world wars

On 17 January 1921, the 109th Observation Squadron was federally recognized as the first aviation unit in the Minnesota National Guard. The squadron was assigned as a divisional observation unit for the 34th Division, at that time recruiting from Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, and North Dakota.[13] The 34th was reorganized as the 1st Infantry Regiment, Minnesota National Guard on 31 January 1920.

On 16 May 1934, the truck driver's union initiated a strike (Minneapolis Teamsters Strike of 1934), which quickly degenerated into open violence in the streets of Minneapolis. Minnesota Governor Floyd B. Olson activated the National Guard, and 4,000 Guardsmen to suppress the chaos. Utilizing roving patrols, curfews, and security details, the 34th quickly restored order, thus enabling negotiated settlement of the labor dispute.[14]

On 18 June 1939, a tornado hit Anoka, Minnesota, and Governor Harold E. Stassen called on the Guard again. 300 Guardsmen patrolled the streets and imposed a quasi-martial law while the community was stabilized.[15]

Prelude to World War II

The expanding war in Europe threatened to draw a reluctant United States into the conflict. As the potential of U.S. involvement in World War II became more evident, initial steps were taken to prepare troops what for lay ahead through "precautionary training."[14] The division was deemed one of the most service-ready units, and Ellard A. Walsh was promoted to major general in June 1940, and then succeeded to division commander in August, following month-long command tours intended to honor senior generals Lloyd D. Ross (Iowa), George E. Leach (Minnesota), and David S. Ritchie (North Dakota) before their retirements.[16]

The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 was signed into law 16 September, and the first conscription in U.S. history during peacetime commenced.[17]

The 34th was subsequently activated on 10 February 1941, with troops from North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Iowa. The division was transported by rail and truck convoys to the newly constructed Camp Claiborne in Rapides Parish, Louisiana near Alexandria.[18]

The soldiers started rigorous training including maneuvers in Alexandria starting 7 April 1941. The climate during the summer was especially harsh. The division then participated in what became known as the Louisiana Maneuvers, and became a well-disciplined, high spirited, and well prepared unit.[18]

In the early phase of the maneuvers, General Walsh, who suffered from chronic ulcers, became too ill to continue in command, and was replaced by Major General Russell P. Hartle on 5 August 1941.[18]

World War II

Organization

34th Infantry Division, Mediterranean Theater of Operations, World War II

- 34th Division Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 133rd Infantry Regiment

- 135th Infantry Regiment

- 168th Infantry Regiment

- 168th Commandos

- 100th Infantry Battalion (9 Sep 43 – 31 Mar 44)

- 442nd Regimental Combat Team (12 Jun 44 – 10 Aug 44)

- 34th Division Artillery, Headquarters and Headquarters Battery

- 125th Field Artillery Battalion (105mm)

- 151st Field Artillery Battalion (105mm)

- 175th Field Artillery Battalion (105mm)

- 185th Field Artillery Battalion (155mm)

- 34th Military Police Company

- 34th Quartermaster Company

- 34th Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized)

- 34th Signal Company

- 109th Engineer (Combat) Battalion

- 109th Medical Battalion

- 734th Ordnance (Light Maintenance) Company

- 1st Ranger Battalion (separate, but activated with 80% 34ID personnel)

In common with other U.S. Army divisions during World War II the 34th was reorganized from a square to a triangular division before seeing combat. The division's three infantry regiments became the 133rd, 135th, and 168th Infantry Regiments, together with supporting units.

On 8 January 1942, the 34th Division was transported by train to Fort Dix, New Jersey to quickly prepare for overseas movement. The first contingent embarked at Brooklyn on 14 January 1942 and sailed from New York the next day. The initial group of 4,508 men stepped ashore at 12:15 hrs on 26 January 1942 at Dufferin Quay, Belfast, Northern Ireland. They were met by a delegation including the Governor (Duke of Abercorn), the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland (John Miller Andrews), the Commander of British Troops Northern Ireland (Lieutenant General Sir Harold Franklyn), and the Secretary of State for Air (Sir Archibald Sinclair).[19]

While in Northern Ireland, Hartle was tasked with organizing an American version of the British Commandos, a group of small "hit and run" forces, and promoted his aide-de-camp, Captain William Orlando Darby to lead the new unit.[19] Darby assembled volunteers, and of the first 500 U.S. Army Rangers, 281 came from the 34th Infantry Division. On 20 May 1942, Hartle was designated commanding general of V Corps and Major General Charles Ryder, a distinguished veteran of World War I, took command of the 34th Division. The division trained in Northern Ireland until it boarded ships to travel to North Africa for Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, in November 1942.

The 34th, under command of Major General Ryder, saw its first combat in French Algeria on 8 November 1942. As a member of the Eastern Task Force, which included two brigades of the British 78th Infantry Division, and two British Commando units, they landed at Algiers and seized the port and outlying airfields. Elements of the 34th Division took part in numerous subsequent engagements in Tunisia during the Allied build-up, notably at Sened Station,[20] Sidi Bou Zid and Faid Pass, Sbeitla, and Fondouk Gap.[21] In April 1943 the division assaulted Hill 609, capturing it on 1 May 1943, and then drove through Chouigui Pass to Tebourba and Ferryville.[22] The Battle of Tunisia was won, and the Axis forces surrendered.

The division skipped the Allied invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) and instead trained intensively for the invasion of the Italian mainland, with the main landings being at Salerno (Operation Avalanche) on 9 September 1943, D-Day, to be undertaken by elements of the U.S. Fifth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Mark Clark. The 151st Field Artillery Battalion went in on D-Day, 9 September, landing at Salerno, while the rest of the division followed on 25 September. Engaging the enemy at the Calore River, 28 September, the 34th, as part of the VI Corps under Major General John Lucas, relentlessly drove north to take Benevento, crossed the winding Volturno three times in October and November, assaulted Monte Patano, and took one of its four peaks before being relieved on 9 December.

In January 1944, the division was back on the front line battering the Bernhardt Line defenses. Persevering through bitter fighting along the Mignano Gap, the 34th used goat herds to clear the minefields.[23] The 34th took Monte Trocchio without resistance as the German defenders withdrew to the main prepared defenses of the Gustav Line. On 24 January 1944, during the First Battle of Monte Cassino they pushed across the Gari River into the hills behind and attacked Monastery Hill which dominated the town of Monte Cassino. While they nearly captured the objective, in the end their attacks on the monastery and the town failed. The performance of the 34th Infantry Division in the mountains has been called one of the finest feats of arms carried out by any soldiers during the war.[24] The unit sustained losses of about 80 per cent in the infantry battalions. They were relieved from their positions 11–13 February 1944. Eventually, it took the combined force of five Allied infantry divisions to finish what the 34th nearly accomplished on its own.

After rest and rehabilitation, the 34th Division landed at the Anzio beachhead 25 March 1944. The division maintained defensive positions until the offensive of 23 May, when it broke out of the beachhead, took Cisterna, and raced to Civitavecchia and the Italian capital of Rome. After a short rest, the division, now commanded by Major General Charles Bolte, drove across the Cecina River to liberate Livorno, 19 July 1944, and continued on to take Monte Belmonte in October during the fighting on the Gothic Line. Digging in south of Bologna for the winter, the 34th jumped off the Spring 1945 offensive in Italy, 15 April 1945, and captured Bologna on 21 April. Pursuit of the routed enemy to the French border was halted on 2 May upon the German surrender in Italy and the end of World War II in Europe.[12]

On 27 June 1944 the 16th SS-Panzer Grenadiers command post in San Vincenzo, Italy was overrun by the 1st Battalion of the 133rd Infantry Regiment. The command post was a town center apartment which had been commandeered, when the owners returned to their apartment they found a signed large leather bound Stieler's Hand Atlas which had been left behind; more on this story here http://generalheinrichvonvietinghoff.wordpress.com/

The division participated in six major Army campaigns in North Africa and Italy. The division is credited with amassing 517 days of front-line combat,[25] more than any other division in the U.S. Army. One or more 34th Division units were engaged in actual combat for 611 days. The 1st Battalion, 133rd Infantry and the Ironman Battalion still holds the record over the rest of the U.S. Army for days in combat. The division was credited with more combat days than any other division in the war. The 34th Division suffered 2,866 killed in action, 11,545 wounded in action, 622 missing in action, and 1,368 men taken prisoner by the enemy, for a total of 16,401 battle casualties. Casualties of the division are considered to be the highest of any division in the theatre when daily per capita fighting strengths are considered. The division's soldiers were awarded ten Medals of Honor, ninety-eight Distinguished Service Crosses, one Distinguished Service Medal, 1,153 Silver Stars, 116 Legion of Merit medals, one Distinguished Flying Cross, 2,545 Bronze Star Medals, fifty-four Soldier's Medals, thirty-four Air Medals, with duplicate awards of fifty-two oak leaf clusters, and 15,000 Purple Hearts.

- Activated: 10 February 1941 (National Guard Division from North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota)

- Overseas: May 1942

- Days of combat: 517

- Distinguished Unit Citations: 3

- Awards:

- Medals of Honor: 11

- Distinguished Service Crosses: 98

- Distinguished Service Medals: 1

- Silver Stars: 1,153

- Bronze Stars: 2,545

- Legions of Merit: 116

- Soldier's Medals: 54

- Purple Hearts: 15,000

- Foreign awards:

- French Croix de Guerre

- Casualties:[26]

- Killed in action: 2,866

- Wounded in action: 11,545

- Missing in action: 622

- Prisoner of war: 1,368

- Total battle casualties: 16,401

- Commanders:

- Maj. Gen. Ellard A. Walsh (February–August 1941)

- Maj. Gen. Russell P. Hartle (August 1941 – May 1942)

- Maj. Gen. Charles W. Ryder (May 1942 – July 1944)

- Maj. Gen. Charles L. Bolte (July 1944 to inactivation)

- Returned to U.S.: 3 November 1945

- Inactivated: 3 November 1945

- Reorganized in Iowa

- Maj. Gen. Ray C. Fountain (19 Nov 1946 – 31 Aug 1954)

- Maj. Gen. Warren C. Wood (1 Sept 1954 – 30 Nov 1962)

- Maj. Gen. Frank P. Williams (1 Dec 1962 – 31 Dec 1967)

- Inactivated: 1968

Cold War to 2001

The 34th was inactivated on 3 November 1945. The division was reformed within the Iowa and Nebraska National Guards in 1946–7, but it disbanded again in 1963, being replaced in part by the 67th Infantry Brigade. It also retained its Division HQ as a Command HQ to supervise training of combat and support units in the former division area for some years. The 47th Infantry Division was headquartered at St Paul, Minn., by 1963, as the National Guard division covering the former 34th's area.

The division was reactivated as a National Guard division (renaming the 47th Division) for Minnesota and Iowa on 10 February 1991 upon the fiftieth anniversary of its federal activation for World War II. At that point the division transitioned into a medium division, with a required strength of 18,062 soldiers.

In 2000 the Minnesota Legislature renamed all of Interstate 35 in Minnesota the "34th Division (Red Bull) Highway," in honor of the division and its service in the World Wars.[27]

Twenty-first century

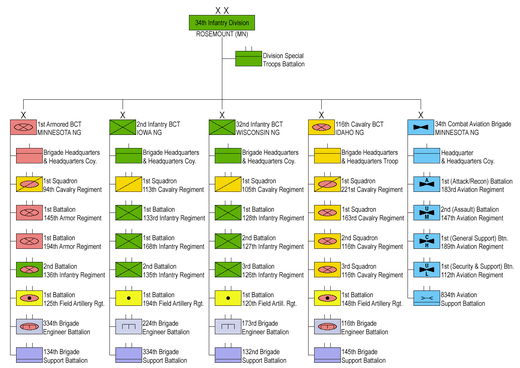

Shortly after its rebirth in 1991, the division began a process of reorganization and change that has continued to the present. One of the most significant developments was transformation from its old brigade structure into brigade combat teams and the broadening of its multi-state base. The Rosemount-based 34th Red Bull Infantry Division provides command and control for 23,000 Citizen-Soldiers in eight different states. In Minnesota the 34th ID includes the 1st Armored Brigade Combat Team, 34th Combat Aviation Brigade, 84th Troop Command and the 347th Regional Support Group. Known as the Red Bulls, the 34th Infantry Division is capable of deploying its Main Command Post, Tactical Command Post, and Division Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion to provide command and control for Army brigades.[28]

Outside Minnesota, the 34th Infantry Division provides training and operational guidance to the 1–112th Security & Support Battalion, ND National Guard; 1–183rd Aviation Battalion, Idaho National Guard; 1–189th Aviation Battalion, Mont. National Guard; 115th Fires Brigade, Wyo. National Guard; 116th Heavy Brigade Combat Team, Idaho National Guard; 141st Maneuver Enhancement Brigade, ND National Guard; 157th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade, Wis. National Guard; 196th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade, SD National Guard; 2nd Brigade Combat Team, Iowa National Guard; and the 32nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team, Wis. National Guard. Combined, the division represents 23,000 Citizen-Soldiers in units stationed across eight different states.

Since October 2001, division personnel served in Operation Joint Forge in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Operation Joint Guardian in Kosovo. Other deployments during the same time period have included Operation Vigilant Hammer in Europe, the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, and Egypt, and Joint Task Force Bravo – Honduras.[25]

The 34th Infantry Division has deployed approximately 11,000 soldiers on operations since October 2001. At home this has included troops deployed for Operation Noble Eagle; abroad units and individual soldiers have deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq.

Afghanistan

- 2004 In May 2004, the 1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment (augmented by Company D, 2nd Battalion, 135th Infantry Regiment), 2nd Brigade, 34th Infantry Division, and with nearly 100 key positions filled by members of the 1st Battalion (Ironman), 133rd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade, 34th Infantry Division, commenced combat operations at 13 Provincial Reconstruction Team sites throughout Afghanistan as part of Operation Enduring Freedom, returning the 34th Infantry Division to combat after 59 years and becoming first unit in the division to wear the Red Bull patch as a right-shoulder combat patch since World War II. The 2011 book Words in the Dust by former 34th ID soldier Trent Reedy is a novel based on the experiences of the 34th ID soldiers assigned to the Farah, Afghanistan PRT.[29]

- 2010 In August 2010, nearly 3,000 Iowa National Guard soldiers, with 28 hometown send-offs, left for a year-long deployment to Afghanistan, making it the largest deployment of the Iowa National Guard since World War II. Augmented by the 1–134th Cavalry Reconnaissance and Surveillance Squadron of the Nebraska National Guard, the brigade conducted pre-mobilization training in Mississippi and California. The troops partnered with Afghan security forces to provide security and assist in training.[30]

Iraq

- 2003–2005 In November 2003, 34th ID's own D 216 ADA from Monticello, MN was activated for deployment in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. From November 2003 through March 2004, the battery trained under the 81st Enhanced Separate Brigade (Armored) in preparation for the deployment at Ft. Lewis, Yakima Training Center, and Ft. Irwin/National Training Center (NTC). While training at NTC, D 216 ADA was reassigned to the 1st CAV, 2nd BCT, 4/5 ADA. In March 2004, the unit moved to Camp New York in Kuwait, then convoyed northward to Baghdad in early April 2004. From April 2004 through March 2005, the Battery performed a wide range of missions to quell a growing insurgency and secure areas of Baghdad ahead of Iraq's first elections. These missions included securing neighborhoods adjacent to Route Irish, maintaining a QRF force for Route Irish, conduct combat operations across a 100 km² area in the vicinity of Al Radwaniyah Presidential Complex (RPC), and gate/perimeter security across several locations on the perimeter of Victory Base Complex (VBC). In recognition of D 216 ADA's exemplary service, the unit was awarded the Valorous Unit Award.

- 2004–2006 In November and December 2004, two platoons of the 634th Military Intelligence Battalion of the 34th Infantry Division activated to train and deploy as AAI RQ-7 Shadow Unmanned Aerial Vehicle operators. The two platoons provided near real time video reconnaissance supporting units from various locations in northern Iraq from the Iran to the Syrian borders. First platoon received an award for being one of the best Shadow units in the Army for their safe flight record and mission effectiveness. The units were activated for over 20 months spending only 12 in Iraq.

- 2005 In January 2005, Company A, 1st Battalion, 194th Armor Regiment (1/194 AR) arrived at Camp Ashraf (about 80 km north of Baghdad) to conduct security and convoy operations in the surrounding area and conducted joint operations with Iraqi Army ahead of the October 2005 Iraqi constitution ratification vote. The 151 man unit was formed from nearly all of the soldiers in the 1/194th and Company A was chosen to honor the unit's lineage of the soldiers who fought to defend the Philippines against the Japanese and the Bataan Death March that followed. The unit was awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation for its exceptional service.[30]

- 2006 In March 2006, 1st Brigade, 34th Infantry Division commenced combat operations in central and southern Iraq as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom, marking the largest single unit deployment for the 34thsince World War II. Returning in July 2007, 1st Brigade served one of the longest consecutive combat operations by a United States National Guard unit (activated for 22 months total with 16 in Iraq).[30] In an effort to recreate the Living Red Bull Patch from Camp Cody, NM, in 1918, the 1st Brigade made its own Living Patch on the parade field at Camp Shelby, MS prior to its deployment to Iraq for OIF 06-08. On 16 July 2009 three members of the Fighting Red Bulls were killed in Basra, Iraq.[31]

- 2008–2009 More than 700 34th Combat Aviation Brigade soldiers deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.

- 2009–2010 The 34th Red Bull Infantry Division deployed more than 1,200 soldiers to Basra, Iraq where they provided command and control for 16,000 U.S. military members and oversaw operations in nine of Iraq’s 18 provinces.

- 2010 The Saint Cloud-based B, 2nd General Support Aviation Battalion, 211th Aviation Regiment, departed in November for a deployment in support of Operation New Dawn. Flying CH-47 Chinook cargo helicopters, the Company B mission is to provide aerial movement of troops, equipment and supplies for support of maneuver, combat and combat service support operations.

- 2011 In June 2011, 1st Brigade deployed to Kuwait, supplying troops for Operation New Dawn. The brigade was augmented with 1–180th Cavalry and 1–160th Field Artillery from the Oklahoma National Guard as well as the 112th Military Police Battalion from the Mississippi National Guard.[30]

- 2013 Personnel from the 34th Infantry Division participated in the exercise Talisman Saber to collectively train within the U.S. Pacific Command Theater of Operations. Division Headquarters personnel focused on offensive and defensive operations while fostering relationships with I Corps, U.S. Army Pacific and the Australian Defense Forces.[28]In May, the 34th Combat Aviation Brigade provided CH-47 and UH-60 helicopters and personnel to local government agencies to fight and contain three wildfires in northwest Minnesota. In 2013, the 34th Combat Aviation Brigade welcomed home the St. Cloud-based Company C, 2nd General Support Aviation Battalion, 211th Aviation Regiment from a deployment in support of Operation Enduring Freedom where they conducted more than 650 medical evacuation missions and flew 1,700 accident-free flight hours. The company also received six new CH-47F Chinook helicopters and trained more than 30 personnel in their operation.[28]In June, the 34th CAB participated in a full-spectrum Warfighter Exercise with the 40th Infantry Division at Fort Leavenworth. During this exercise, the brigade staff was able to successfully integrate with different levels of command and adjacent units.[28]

Current structure

![]() 34th Infantry Division exercises training and readiness oversight of the following elements, but they are not organic:[32]

34th Infantry Division exercises training and readiness oversight of the following elements, but they are not organic:[32]

- Main Command Post (MCP)

- Special Troops Battalion (STB)

- 1st Armored Brigade Combat Team (MN NG)[33]

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 1st Squadron, 94th Cavalry Regiment (Armored Recon)[34]

- 1st Battalion, 145th Armor Regiment[35][36]

- 1st Battalion, 194th Armor Regiment[37]

- 2nd Battalion, 136th Infantry Regiment

- 1st Battalion, 125th Field Artillery Regiment[38]

- 334th Brigade Engineer Battalion

- 134th Brigade Support Battalion[39]

- 2nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IA NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 1st Squadron, 113th Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) (IA NG)

- 1st Battalion, 133rd Infantry Regiment (IA NG)

- 1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment (IA NG)

- 2nd Battalion, 135th Infantry Regiment[40]

- 1st Battalion, 194th Field Artillery Regiment[41]

- 224th Brigade Engineer Battalion [42]

- 334th Brigade Support Battalion[43]

- 32nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (WI NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 1st Squadron, 105th Cavalry Regiment (RSTA)

- 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry Regiment

- 3rd Battalion, 126th Infantry Regiment

- 1st Battalion, 120th Field Artillery Regiment

- 173rd Brigade Engineer Battalion

- 132nd Brigade Support Battalion[44]

- 116th Cavalry Brigade Combat Team (ID NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company (ID NG)

- 1st Squadron, 221st Cavalry Regiment (Armored Recon) (NV NG)[45]

- 1st Squadron, 163rd Cavalry Regiment (Combined Arms) (MT NG)

- 2nd Squadron, 116th Cavalry Regiment (Combined Arms) (ID NG)

- 3rd Squadron, 116th Cavalry Regiment (Combined Arms) (OR NG)

- 1st Battalion, 148th Field Artillery Regiment (ID NG)

- 116th Brigade Engineer Battalion

- 145th Brigade Support Battalion (ID NG)

- 34th Combat Aviation Brigade (MN NG)

- Headquarters & Headquarters Company

- 1st Battalion, 112th Aviation Regiment (Support & Security) (ND NG)

- 2nd Battalion, 147th Aviation Regiment (Assault) (MN NG)

- 1st Battalion, 183rd Aviation Regiment (Attack) (ID NG)

- 1st Battalion, 189th Aviation Regiment (General Support) (MT NG)

- 834th Aviation Support Battalion (MN NG)

Attached units

- 115th Fires Brigade (WY NG)

- 141st Maneuver Enhancement Brigade (ND NG)

- 157th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade (WI NG)

- 347th Regional Support Group[46] (formerly 34th Division Support Command)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 147th Personnel Services Battalion

- 347th Personnel Services Detachment

- 34th Military Police Company

- 257th Military Police Company

- 114th Transportation Company

- 204th Medical Company (Area Support)

- 247th Finance Detachment

- 34th Infantry Division Band

- Service Battery, 1st Battalion, 214th Field Artillery Regiment (GA NG)

- Companies A and B, 2nd Battalion, 123rd Armor Regiment (KY ARNG)

Commanders

- Maj. Gen. David H. Lueck

- Maj. Gen. Clayton A Hovda

- Maj. Gen. Gerald A. Miller

- Maj. Gen. Rodney R. Hannula

- Maj. Gen. Larry Shellito

- Maj. Gen. Rick D. Erlandson

- Maj. Gen. Richard C. Nash

- Maj. Gen. David Elicerio

- Maj. Gen. Neal Loidolt

- Brig. Gen. Jon Jensen[25]

References

- ↑ "Minnesota National Guard".

- ↑ United States Army, Division, 34th (1945). The Story of the 34th Infantry Division – Louisiana to Piza. Information and Education Section, MTOUSA. p. 1.

- ↑ "34th Infantry Division (ARNG)". United States Army Combined Arms Center. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ "Guard101.ppt". Slide 6. Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Corell, Ben (Winter 2012). 34th Infantry Division Association. "2nd Brigade Combat Team, 34th Infantry Div 2010–11 Afghan Deployment Report" (PDF). The 34th ID Association Newsletter: 4. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Davis Jr., Henry Blaine (1998). Generals in Khaki. Pentland Press, Inc. p. 43. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151.

- ↑ "34th Infantry Division". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ McGrath, John J. (2004). The Brigade: A History Its Organization and Employment in the US Army (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. p. 169.

- ↑ Longden, Tom (October 19, 2009). "Marvin Cone". Des Moines Register. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ↑ "34th Infantry Division "Red Bull"". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ Davis Jr., Henry Blaine (1998). Generals in Khaki. Pentland Press, Inc. p. 247. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151.

- 1 2 "34th Infantry Division". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ http://www.nationalguard.mil/news/todayinhistory/january.aspx, accessed December 2012.

- 1 2 Johnson, Jack (Winter 2012). "Allies". Newsletter for Members and Friends of the Military Historical Society of Minnesota. XX (1): 1–3.

- ↑ "Anoka, Minnesota Tornado". United Press. GenDisasters. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Army and Navy Journal. 77. Washington, DC: Army and Navy Journal, Incorporated. 1904. p. 38.

Elevation of Generals Ross, Leach and Ritchie is merely an honor to outstanding senior officers and they will not be recognized as major generals by the War Department, no pay therefore being involved.

- ↑ "Background of Selective Service". Selective Service System. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Camp Claiborne, Louisiana". Western Maryland's Historical Library. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- 1 2 Jeffers, H. Paul (2007). Onward We Charge: The Heroic Story of Darby's Rangers in World War II. Chapter 2: Penguin Books.

- ↑ Staab, William (2009). Not for Glory. Vantage Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-533-16121-8.

- ↑ Howe, George. "U.S. Army in World War II, Mediterranean Theater of Operations – Northwest Africa: Seizing the Initiative in the West". Hyperwar Foundation. pp. 423–437. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ↑ Center of Military History (1943). To Bizerte With The II Corps. Historical Division, War Department. pp. 37–50.

- ↑ Atkinson, Rick (2008). The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944. Macmillan. p. 260.

- ↑ Majdalany, Fred (1957). Cassino: Portrait of a Battle. Longman, Green and Co. p. 87.

- 1 2 3 "History of the 34th Infantry Division". Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths in World War II, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ↑ 2000 Minn. Laws ch. 281, codified at Minn. Stat. 161.14 subd. 46.

- 1 2 3 4 "2013 Annual Report and 2014 Objectives" (PDF). Minnesota National Guard. 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Page Not Found – Chicago Tribune".

- 1 2 3 4 "Decade of change transforms Red Bulls". Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ "Our Fallen Troops". Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ "Torchbearer Special Report" (PDF). AUSA. December 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Minnesota National Guard Units".

- ↑ "1st Squadron, 94th Cavalry". Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ "1st Battalion, 145th Armor Regiment". Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ↑ http://www.minnesotanationalguard.org/units/134BC/assets/1-34%20ABCT%20Unit%20Overview_19SEP14.pdf

- ↑ "1st Combined Arms Battalion, 194th Armor Regiment". Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ "1st Battalion, 125th Field Artillery". Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ "134th Brigade Support Battalion". Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ "2nd Battalion, 135th Infantry Regiment". Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ↑ "1st Battalion, 194th Field Artillery Regiment". Iowa National Guard. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ http://www.thegazette.com/subject/life/people-places/passing-the-torch-ceremony-to-inactivate-cedar-rapids-based-national-guard-battalion-20160915

- ↑ "334th Brigade Support Battalion". Global Security. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ "132nd Support Battalion". Global Security. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ http://www.nv.ngb.army.mil/nvng/index.cfm/public-affairs/news-releases/bradley-vehicles-arrival-signals-new-era-new-combat-team-for-1-221st-cavalry1/

- ↑ "347th Regional Support Group". Minnesota National Guard. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

Bibliography

- Davis Jr., Henry Blaine (1998). Generals in Khaki. Pentland Press, Inc. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 34th Infantry Division (United States). |

- 34th Infantry Division webpage

- 34th Infantry Division Facebook page

- 34th Infantry Division Association

- World War II Reenactors – 34th Infantry Division 133rd

- 34th Division in Italy, World War II

- Wisconsin National Guard

- UNIT DESIGNATIONS IN THE ARMY MODULAR FORCE

- Camp Cody – 34th Division WWI

- 34th Division Soldiers respond to John Kerry comment

- The short film Big Picture: The Red Bull Attacks is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- 34th Infantry Division – Louisiana to Pisa (1945)

- Major Russell Hartle, leading the 34th Division to Northern Ireland in 1942