California gubernatorial recall election

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|

County results (recall question) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Elections in California | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

The 2003 California gubernatorial recall election was a special election permitted under California state law. It resulted in voters replacing incumbent Democratic Governor Gray Davis with Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger. Davis was ineligible to run for a third term due to term limits after the recall election. The recall effort spanned the latter half of 2003. Other California governors, including Pat Brown, Ronald Reagan, Jerry Brown, and Pete Wilson, had faced unsuccessful recall attempts.

After several legal and procedural efforts failed to stop it, California's first-ever gubernatorial recall election was held on October 7, and the results were certified on November 14, 2003, making Davis the first governor recalled in the history of California, and just the second in U.S. history (the first was North Dakota's 1921 recall of Lynn Frazier).[1] In 1988, a recall election had been scheduled for Arizona governor Evan Mecham, but he was impeached, convicted, and removed from office before his qualified recall election could occur. California is one of 19 states that allow recalls.[2] The third U.S. gubernatorial recall election occurred in Wisconsin in 2012.

California recall history

The California recall process became law in 1911 as the result of Progressive Era reforms that spread across the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The ability to recall elected officials came along with the initiative and referendum processes. The movement in California was spearheaded by Republican then-Governor Hiram Johnson, a reformist, who called the recall process a "precautionary measure by which a recalcitrant official can be removed." No illegality has to be committed by politicians in order for them to be recalled. If an elected official commits a crime while in office, the state legislature can hold impeachment trials. For a recall, only the will of the people is necessary to remove an official.[3]

Before the successful recall of Gray Davis, no California statewide official had ever been recalled, though there had been 117 previous attempts. Only seven of those even made it onto the ballot, all for state legislators. Every governor since Ronald Reagan in 1968 has been subject to a recall effort, but Gray Davis was the first governor whose opponents gathered the necessary signatures to qualify for a special election. Davis also faced a recall petition in 1999, but that effort failed to gain enough signatures to qualify for the ballot. The 1999 recall effort was prompted by several actions taken by Davis, including his preventing the enactment of Proposition 187 by keeping it from being appealed to the US Supreme Court and his signing of two new highly restrictive gun-control laws. As Davis's recall transpired before he had served half of his term as governor, he remains eligible to serve another term, should he win a future election for the California governor post.

Nineteen states, along with the District of Columbia, allow the recall of state officials,[4] but Davis's recall was only the second in US history. The first governor recall occurred in 1921 when North Dakota's Lynn J. Frazier was recalled over a dispute about state-owned industries, and was replaced by Ragnvald A. Nestos.[5] The third recall occurred in Wisconsin in 2012.

Background

California law

Under California law, any elected official may be the target of a recall campaign.[6] To trigger a recall election, proponents of the recall must gather a certain number of signatures from registered voters within a certain time period. The number of signatures statewide must equal 12% of the number of votes cast in the previous election for that office.[7] For the 2003 recall election, that meant a minimum of 897,156 signatures, based on the November 2002 statewide elections, but 1.2 million were needed to ensure that there were enough valid signatures.[8]

The effort to recall Gray Davis began with Republicans Ted Costa, Mark Abernathy, and Howard Kaloogian, who filed their petition with the California Secretary of State and started gathering signatures. The effort was not taken seriously, until Rep. Darrell Issa, who hoped to run as a replacement candidate for governor, donated $2 million towards the effort. This infusion of money allowed Costa and Kaloogian to step up their efforts. Eventually, proponents gathered about 1.6 million signatures, of which 1,356,408 were certified as valid.[8]

Under most circumstances in which a recall campaign against a statewide elected official has gathered the required number of signatures, the governor is required to schedule a special election for the recall vote.[9] If the recall campaign qualified less than 180 days prior to the next regularly scheduled election, then the recall becomes part of that regularly scheduled election.[10] In the case of a recall against the governor, the responsibility for scheduling a special election falls on the lieutenant governor,[11] who in 2003 was Cruz Bustamante.[12]

Political climate

The political climate was largely shaped by the then-recent and costly California electricity crisis of the early 2000s, in which many saw the cost of their monthly energy bills triple.

The public, due to the complex nature of the energy crisis, held Davis partly responsible. General speculation regarding the factors influencing the recall's outcome continues to center on the idea that Californians simply voted for a "change" because Davis had mismanaged the events leading up to the energy crisis, e.g., Davis had not fought more vigorously for Californians against the energy fraud nor had he pushed for legislative or emergency executive action soon enough; because Davis had signed deals agreeing to pay energy companies fixed yet inflated prices for years to come based on those paid during the crisis; and/or because the fraudulent corporations had prevailed, and a corporate-friendly Republican governor could politically shield California from further corporate fraud. Others speculated that the corporations involved sought not only profit, but were acting in concert with Republican political allies to cause political damage to the nationally influential Democratic governor. Still others, such as Arianna Huffington, argued that Davis' persistent fundraising and campaign contributions from various companies, including energy companies, made him unable to confront his contributors. Davis accepted $2,000,000 from the California Correctional Peace Officers Association and used his political connections to pass an estimated $5,000,000,000 raise for them over the coming years. This led many people throughout California to believe Davis was guilty of corruption even if he did not meet the standard necessary for prosecution.[13]

Arguments about the recall drive

Backers of the recall effort cited Davis's alleged lack of leadership combined with California's weakened and hurt economy. According to the circulated petition:

[Governor Davis' actions were a] gross mismanagement of California Finances by overspending taxpayers' money, threatening public safety by cutting funds to local governments, failing to account for the exorbitant cost of the energy, and failing in general to deal with the state's major problems until they get to the crisis stage.

Opponents of the recall said the situation was more complicated, for several reasons.

The entire United States and many of its economic trading partners had been in economic recession. California was hit harder than other states at the end of the speculative bubble known as the "dot-com bubble"—from 1996 to 2000—when Silicon Valley was the center of the internet economy. California state expenditures soared when the government was flush with revenues. Some Californians blamed Davis and the state legislature for continuing to spend heavily while revenues dried up, ultimately leading to record deficits.

Also, the California electricity crisis of 2000–2001 caused great financial damage to the state of California. There is much consternation among the citizens of California regarding Davis's handling of the crisis; see that article for more. The legal issues still were not resolved in time to alleviate California's dire need for electricity, and the state instituted "rolling blackouts" and in some cases instituted penalties for excess energy use. In the recall campaign, Republicans and others opposed to Davis's governance sometimes charge that Davis did not "respond properly" to the crisis. In fact most economists disagree, believing that Davis could do little else—and anyone in the governor's office would have had to capitulate as Davis did, in the absence of Federal help. The Bush administration rejected requests for federal intervention, responding that it was California's problem to solve.[14] Still, subsequent revelations of corporate accounting scandals and market manipulation by some Texas-based energy companies did little to quiet the criticism of Davis's handling of the crisis.

Furthermore, there is a high correlation between the success of the recall signature gathering effort and the inability for the California Legislature and the governor to agree on a new state budget. The new year's California budget was finally passed on August 1, 2003, several days after the recall drive qualified, and many believe the deadlock involved in the budget negotiations added fuel to the fire driving the recall effort. Some were further antagonized by the fact that the budget ultimately passed relied on loans and borrowing—which they said amounted to not fixing California's budget problems at all.

Additionally, many Republicans believe that California's taxes are too high, discouraging investment and driving businesses out of the state. Many candidates also criticized Davis's immigration policy, and were particularly enraged by Davis's seeming support of the court ruling striking down most of Proposition 187 as unconstitutional and his more recent support for issuing driver's licenses to illegal immigrants.

Many other California governors have faced recall attempts and many others have governed through tough economic circumstances, but none ever faced a special recall election until Davis. Some political experts believe a "perfect storm" of circumstances led to the success of the recall drive.

Davis swept into the governor's office in 1998 in a landslide victory and a 60% approval rating as California's economy roared to new heights during the dot-com boom. Davis took his mandate from the voters and sought out a centrist political position, refusing some demands from labor unions and teachers' organizations on the left. The Democratic Davis, already opposed by Republicans, began losing favor among members of his own party. Nevertheless, Davis's approval ratings remained above 50%.

When the California electricity crisis slammed the state in 2001, Davis was blasted for his slow and ineffective response. His approval rating dropped into the 30s and never recovered. When the energy crisis settled down, Davis's administration was hit with a fund-raising scandal. California had a $95 million contract with Oracle Corporation that was found to be unnecessary and overpriced by the state auditor. Three of Davis's aides were fired or resigned after it was revealed that the governor's technology adviser accepted a $25,000 campaign contribution shortly after the contract was signed. The money was returned, but the scandal fueled close scrutiny of Davis's fundraising for his 2002 re-election bid.

In the 2002 primary election, Davis ran unopposed for the Democratic nomination. He spent his campaign funds on attack ads against California Secretary of State Bill Jones and Los Angeles mayor Richard Riordan, the two well known moderates in the Republican primary. The result was that his opponent in the general election was conservative Republican and political newcomer Bill Simon, who was popular within his own party but unknown by the majority of the state population. The intense criticism of both candidates caused Davis and Simon to run one of the most negative campaigns in recent state history. The attacks on both sides turned off voters and suppressed turnout; Davis ultimately won with 47% of the vote. The suppressed turnout had the effect of lowering the threshold for the 2003 recall petition to qualify.

On December 18, 2002, just over a month after being reelected, Davis announced that California would face a record budget deficit possibly as high as $35 billion, a forecast $13.7 billion higher than one a month earlier. The number was finally estimated to be $38.2 billion, more than all 49 other states' deficits combined. Already suffering from low approval ratings, Davis's numbers hit historic lows in April 2003 with 24% approval and 65% disapproval, according to a California Field Poll. Davis was almost universally disliked by both Republicans and Democrats in the state and a recall push was high.

A hot button issue that seemed to galvanize the public was the vehicle license fee increase Davis implemented under provisions of legislation passed by his predecessor which originally reduced the fees.[15] On June 20, 2003 the Davis administration reinstituted the full vehicle license fee, and to date the action has withstood legal challenge. The action was a key step in the plan to close the $38 billion shortfall in the 2003–2004 budget. The increase tripled the vehicle license fee for the average car owner, and began appearing in renewal notices starting August 1. The California state budget passed in late July 2003 included the projected $4 billion in increased vehicle license fee revenue.

Proponents of the Governor's recall characterized the increase as a tax hike and used it as an issue in the recall campaign. In mid-August 2003, Davis floated a plan to reverse the increase, making up the revenue with taxes on high income earners, cigarettes, and alcoholic beverages.

When Gray Davis was recalled and Arnold Schwarzenegger was elected governor in October 2003, Schwarzenegger vowed that his first act as governor would be to revoke the vehicle license fee increase. On November 17, just after his inauguration, Gov. Schwarzenegger signed Executive Order S-1-03, rescinding the vehicle license fee retroactive to October 1, 2003 when the fee increase went into effect. Analysts predicted that this would add more than $4 billion to the state deficit. Schwarzenegger did not indicate how cities and counties would be reimbursed for the lost revenue they receive from the license fee to support public safety and other local government activities.

Recall election

Background

On February 5, 2003, anti-tax activist Ted Costa announced a plan to start a petition drive to recall Davis. Several committees were formed to collect signatures, but Costa's Davis Recall Committee was the only one authorized by the state to submit signatures. One committee "Recall Gray Davis Committee", organized by Republican political consultant Sal Russo and former Republican assemblyman Howard Kaloogian played a supporting role in drumming up support. Kaloogian served as chairman, Russo as chief strategist of the committee.[16] After the recall both Kaloogian and Russo went on to found Move America Forward.[17][18]

By law, the committee had to collect signatures from registered California voters amounting to 12% of the number of Californians who voted in the previous gubernatorial election (November 2002) for the special recall vote to take place. The organization was given the go-ahead to collect signatures on March 25, 2003. Organizers had 160 days to collect signatures. Specifically, they had to collect at least 897,158 valid signatures from registered voters by September 2, 2003.

The recall movement began slowly, largely relying on talk radio, a website, cooperative e-mail, word-of-mouth, and grassroots campaigning to drive the signature gathering. Davis derided the effort as "partisan mischief" by "a handful of right-wing politicians" and called the proponents losers. Nevertheless, by mid-May recall proponents said they had gathered 300,000 signatures. They sought to gather the necessary signatures by July in order to get the special election in the fall of 2003 instead of March 2004 during the Democratic presidential primary election, when Democratic Party turnout would presumably be higher. The effort continued to gather signatures, but the recall was far from a sure thing and the proponents were short on cash to promote their cause.

The movement took off when wealthy U.S. Representative Darrell Issa, a Republican representing San Diego, California, announced on May 6 that he would use his personal money to push the effort. All told, he contributed $1.7 million of his own money to finance advertisements and professional signature-gatherers. With the movement accelerated, the recall effort began to make national news and soon appeared to be almost a sure thing. The only question was whether signatures would be collected quickly enough to force the special election to take place in late 2003 rather than in March 2004.

The Issa recall committee's e-mail claimed that California Secretary of State Kevin Shelley, belonging to the same party as the Governor, resisted certification of the recall signatures as long as possible. By mid-May, the recall organization was calling for funds to begin a lawsuit against Shelley, and publicly considered a separate recall effort for the Secretary of State (also an elected official in California).

However, by July 23, 2003, recall advocates turned in over 110% of the required signatures, and the Secretary of State announced that the signatures had been certified and a recall election would take place. Proponents had set a goal of 1.2 million to provide a buffer in case of invalid signatures. In the end, there were 1,363,411 valid signatures out of 1,660,245 collected (897,156 required). The next day, Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante announced that Davis would face a recall election on October 7. California's Constitution requires that a recall election be held within 80 days of the date the recall petition is certified, or within 180 days if a regularly scheduled statewide election comes within that time. Had the petition been certified at the deadline of September 2, the election would have been held in March 2004, the next scheduled statewide election. Instead, Bustamante chose a date 76 days from the date of certification, October 7. This was to be the second gubernatorial recall election in the United States history and the first in the history of California.

Later that month, the committee's periodic e-mail said that state funds were being illegally used to fight the recall effort. In particular, four million dollars of California State University funds were said to have been funded to educate union members in "Workers Against Recall" or "WAR." Recall supporters organized an authorized (licensed by local police) march opposite a hotel hosting a WAR seminar on August 15, 2003. News video showed a dozen union members with WAR T-shirts crossing the street and assaulting marchers, sending one to a hospital.

Notable candidates

The October 7 recall election had many declared candidates, several of whom were prominent celebrities. In total, there were 135 candidates who qualified for the ballot in the election, including four candidates who obtained at least 1% of the vote:

Democratic

- Cruz Bustamante, lieutenant governor[19]

Green

- Peter Camejo, 2002 Green Party candidate for governor

Republican

Campaign

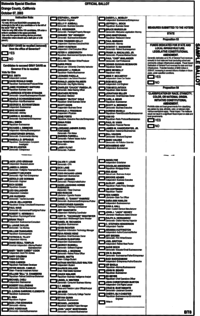

The ballot consisted of two questions; voters could vote on one or the other, or on both. The first question asked whether Gray Davis should be recalled. It was a simple yes/no question, and if a majority voted no, then the second question would become irrelevant and Gray Davis would remain California governor. If a majority voted yes, then Davis would be removed from office once the vote was certified, and the second question would determine his successor. Voters had to choose one candidate from a long list of 135 candidates. Voters who voted against recalling Gray Davis could still vote for a candidate to replace him in case the recall vote succeeded. The candidate receiving the most votes (a plurality) would then become the next governor of California. Certification by the Secretary of State of California would require completion within 39 days of the election, and history indicated that it could require that entire time frame to certify the statewide election results. Once the results were certified, a newly elected governor would have to be sworn into office within 10 days.

Those Californians wishing to run for governor were given until August 9 to file. The requirements to run were relatively low and attracted a number of interesting and strange candidates. A California citizen needed only to gather 65 signatures from their own party and pay a nonrefundable $3,500 fee to become a candidate, or in lieu of the fee collect up to 10,000 signatures from any party, the fee being prorated by the fraction of 10,000 valid signatures the candidate filed. No candidate in fact collected more than a handful of signatures-in-lieu, so that all paid almost the entire fee. In addition, however, candidates from recognized third parties were allowed on the ballot with no fee if they could collect 150 signatures from their own party.

The low requirements attracted many "average joes" with no political experience to file as well as several celebrity candidates. Many prominent potential candidates chose not to run. These included Democratic U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, widely regarded as the most popular statewide office-holding Democrat in California, who cited her own experience with a recall drive while she was mayor of San Francisco. Darrell Issa, who bankrolled the recall effort and said he would run for governor, abruptly dropped out of the race on August 7 among accusations that he had bankrolled the recall effort solely to get himself into office. Issa claimed that Schwarzenegger's decision to run did not affect his decision and he dropped out because he was assured that there were several strong candidates running in the recall.[23] The San Francisco Chronicle claimed that Davis's attacks on Issa's "checkered past" and polls showing strong Republican support for Schwarzenegger caused Issa to withdraw.[23] Former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan and actor Arnold Schwarzenegger (a fellow Republican) agreed that only one of them would run; when Schwarzenegger announced on The Tonight Show that he would be a candidate, Riordan dropped out of the race. Riordan was surprised and those close to him say angered when he learned Schwarzenegger was running. Riordan did end up endorsing Schwarzenegger, but his endorsement was described as terse and matter-of-fact in contrast to his usually effusive way.[23] State Insurance Commissioner John Garamendi (a Democrat) announced on August 7 that he would be a candidate for governor. However, just two days later and only hours before the deadline to file, he announced "I will not engage in this election as a candidate", adding, "this recall election has become a circus." Garamendi had been under tremendous pressure to drop out from fellow Democrats who feared a split of the Democratic vote between him and Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante should the recall succeed.

On September 3, five top candidates—independent Arianna Huffington, Democratic Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante, Green Party candidate Peter Camejo, Republican State Senator Tom McClintock, and former baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth—participated in a live television debate. Noticeably absent was Arnold Schwarzenegger who opponents charged was not adequately prepared.[24] Schwarzenegger had repeatedly stated that he would not participate in such events until later in the election cycle. Prior to this first debate, Gov. Davis spent 30 minutes answering questions from a panel of journalists and voters.

Due to the media attention focused on some candidates, GSN held a game show debate entitled Who Wants to Be Governor of California? – The Debating Game, a political game show featuring seven candidates unlikely to win the election, including former child star Gary Coleman and porn star Mary Carey.

Several candidates who would still be listed on the ballot dropped out of the campaign before the October 7 election. On August 23, Republican Bill Simon (the 2002 party nominee) announced he was dropping out. He said, "There are too many Republicans in this race and the people of our state simply cannot risk a continuation of the Gray Davis legacy." Simon did not endorse any candidates at the time, but several weeks later he endorsed front-runner Arnold Schwarzenegger, as did Darrell Issa, who had not filed for the race. On September 9, former MLB commissioner and Los Angeles Olympic Committee President Peter Ueberroth withdrew his candidacy in the recall election.

On September 24, the remaining top five candidates (Schwarzenegger, Bustamante, Huffington, McClintock, and Camejo) gathered in the University Ballroom at California State University, Sacramento, for a live televised debate[25] that resembled the red-carpet premiere of a movie in Hollywood. Schwarzenegger's marquee name attracted large crowds, a carnival atmosphere, and an army of hundreds of credentialed media from around the world. While the candidate and his staff rode on buses named Running Man and Total Recall, the reporters' buses were named after Predator.[26]

The aftermath of the debate was swift. On September 30, author Arianna Huffington withdrew her candidacy on the Larry King Live television program and announced that she was opposing the recall entirely in light of Arnold Schwarzenegger's surge in the polls. Apparently in response to her withdrawal, Cruz Bustamante endorsed her plan for public financing of election campaigns, an intended anti-corruption measure.

On October 7, the recall election was held, and voters decisively voted to recall Davis and to elect Schwarzenegger as his replacement. At 10 p.m. local time, Davis conceded that he had lost to Schwarzenegger, saying, "We've had a lot of good nights over the last 20 years, but tonight the people did decide that it's time for someone else to serve, and I accept their judgment." About 40 minutes later, in his acceptance speech, Schwarzenegger said, "Today California has given me the greatest gift of all: You've given me your trust by voting for me. I will do everything I can to live up to that trust. I will not fail you."

The result was officially certified on November 14 and Schwarzenegger was sworn in on November 17. 4,206,284 voters chose Schwarzenegger for governor, while 4,007,783 voted to keep Davis in office; thus, worries about a potentially anomalous result were assuaged.

Election logistics

Concurrent alternatives

On July 29, 2003, federal judge Barry Moskowitz ruled section 11382 of the California election code unconstitutional. The provision required that only those voters who had voted in favor of the recall could cast a vote for a candidate for governor. The judge ruled that a voter could vote for or against the recall election and still vote for a replacement candidate. Secretary of State Kevin Shelley did not contest the ruling, thereby setting a legal precedent.

Availability of Spanish-speaking poll workers

In August, a federal judge in San Jose announced that he was considering issuing an order postponing the recall election. Activists in Monterey County had filed suit, claiming that Monterey County, and other counties of California affected by the Voting Rights Act were violating the act by announcing that, because of budgetary constraints, they were planning on hiring fewer Spanish-speaking poll watchers, and were going to cut back by almost half the number of polling places. On September 5, a three-member panel of federal judges ruled that the county's election plans did not constitute a violation of the federal Voting Rights Act.

Punch card ballots

A lawsuit filed in Los Angeles by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) claimed that the use of the "hanging chad" style punch-card ballots still in use in six California counties (Los Angeles, Mendocino, Sacramento, San Diego, Santa Clara, and Solano) were in violation of fair election laws. U.S. District Judge Stephen V. Wilson in Los Angeles ruled on August 20 that the election would not be delayed because of the punch-card ballots. The ruling was appealed, and heard by three judges in the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. On September 15 the judges issued a unanimous ruling postponing the recall election until March 2004 on the grounds that the existence of allegedly obsolete voting equipment in some counties violated equal protection, thus overruling the lower district court which had rejected this argument.

Recall proponents questioned why punch-card ballots were adequate enough to elect Governor Davis, but were not good enough to recall him. Proponents planned to appeal the postponement to the U.S. Supreme Court. However, an 11-judge panel, also from the ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals quickly gathered to rehear the controversial case. On the morning of September 23, the panel reversed the three-judge ruling in a unanimous decision, arguing that the concerns about the punch-card ballots were outweighed by the harm that would be done by postponing the election.

Further legal appeals were discussed but did not occur. The ACLU announced it would not make an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, and Davis was widely quoted in the press as saying "Let's just get it over with." Thus the election proceeded as planned on October 7.

Polling

Public opinion was divided on the recall, with many passionately-held positions on both sides of the recall election. Californians were fairly united in their disapproval of Governor Davis's handling of the state, with his approval numbers in the mid-20s. On the question of whether he should be recalled, Californians were more divided, but polls in the weeks leading up to the election consistently showed that a majority would vote to remove him.

Polls also showed that the two leading candidates, Lt. Governor Cruz Bustamante, a Democrat, and Hollywood actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, were neck and neck with about 25–35% of the vote each, and Bustamante with a slight lead in most polls. Republican State Senator Tom McClintock also polled in the double-digits. Remaining candidates polled in the low single digits. Polls in the final week leading up to the election showed support for Davis slipping and support for Schwarzenegger growing.

Many observers outside California, and some members of the press, consistently called the recall chaos and madness as well as a media circus and nightmare. With the candidacies of a few celebrities and many regular Californians, the entire affair became a joke to some (there were tongue-in-cheek references to Schwarzenegger's role within the science fiction film Total Recall) as well as an "only-in-California" event. Nevertheless, most Californians took the recall seriously, with the future of the governor's office at stake. The election drew in many Californians who had never voted before and voter registration increased.

Results

The ballot had two questions.

The first question was whether Davis, the sitting governor, should be recalled; those voting on it were 55.4% in favor of recall and 44.6% opposed.

The second question was who would replace the governor in the event of a majority voted on the recall question. Among those voting on the potential replacement, Schwarzenegger received a plurality of 48.6%, by surpassing Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante's 31.5% – about a 3-to-2 ratio. Republican Tom McClintock received 13.5% of the vote – less than half the share of the candidate he trailed. Green Party candidate Peter Camejo polled 2.8%, trailing the third-place candidate almost 4-to-1. Each remaining candidate polled 0.6% or less.

Schwarzenegger's votes exceeded those for the next five candidates combined, despite the presumed division of Republican voters between him and McClintock. There were also more votes for Schwarzenegger than votes against recalling Davis, avoiding the theoretical scenario of the replacement having less support than the recalled governor.

Following the election, all 58 of California's counties had 28 days (until November 4, 2003) each to conduct a countywide canvass of their votes. Counties used this time to count any absentee ballots or provisional ballots not yet counted, to reconcile the number of signatures on the roster of registered voters with the number of ballots recorded on the ballot statement, to count any valid write-in votes, to reproduce any damaged ballots, if necessary, and to conduct a hand count of the ballots cast in 1% of the precincts, chosen at random by the elections official.

Counties then had seven days from the conclusion of canvassing (November 11, 2003, 35 days after the election) to submit their final vote totals to the California Secretary of State's office. The Secretary of State had to certify the final statewide vote by 39 days (until November 15) after the election. The vote was officially certified on November 14, 2003. Once the vote was certified, governor-elect Schwarzenegger had to be sworn into office within ten days.[27] His inauguration took place on November 17.

| Key: | Withdrew prior to contest |

| California gubernatorial recall election, 2003[28][29][30] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote on recall | Votes | Percentage | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 4,976,274 | 55.4% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 4,007,783 | 44.6% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Invalid or blank votes | 429,431 | 4.6% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Totals | 9,413,488 | 100.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Voter turnout | 61.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Party | Candidate | Votes | Percentage | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Republican | Arnold Schwarzenegger | 4,206,284 | 48.6% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Democratic | Cruz Bustamante | 2,724,874 | 31.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Republican | Tom McClintock | 1,161,287 | 13.4% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Green | Peter Camejo | 242,247 | 2.8% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Independent | Arianna Huffington | 47,505 | 0.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| All other listed and write-in candidates (see below for details) | 275,719 | 3.2% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Invalid or blank votes | 755,575 | 8.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Totals | 9,413,490 | 100.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Voter turnout | 61.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Republican gain from Democratic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note that San Bernardino County did not report write-in votes for individual candidates.[29]

See also

References

- ↑ Baldassare, Mark; Katz, Cheryl (2008). The Coming Age of Direct Democracy: California's Recall and Beyond. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 11. ISBN 9780742538719. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- ↑ Jennie Bowser. "Recall of State Officials". Ncsl.org. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ↑ Hiram Johnson. "Inaugural Address". Governors of California. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Recall of State Officials". National Conference of State Legislatures. July 12, 2011. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ↑ "2003 California Recall Election". University of California. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ↑ Constitution of California, Art. II, Sec. 13. The process is defined in Constitutional Article II, Sections 13–20 and California Elections Code Div. 11.

- ↑ Cal. Const., Art. II, Sec. 14(b).

- 1 2 Archived January 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Cal. Const. Art. II, Sec 15(a)

- ↑ Cal. Const. Art. II, Sec 15(b)

- ↑ Cal. Const. Art. II, Sec. 17

- ↑ "History of California Constitutional Officers" (PDF). sos.ca.gov. 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ↑ O'Hehir, Andrew (2001-01-27). "Gov. Davis and the failure of power – California". Salon.com. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ↑ Harriet Chiang; Chronicle Legal Affairs Writer (2001-05-14). "Davis urges Bush to cap 'obscene' power prices". Sfgate.com. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ↑ "HOT TOPICS" – IGS Library/UC Berkeley

- ↑ "California Gov. Davis Faces Recall Effort". CNN. 2003-06-17. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Marsetta, Diane (2004). "Moving America One Step Forward And Two Steps Back". PR Watch.com. Center for Media and Democracy. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ↑ "About Us". Move America Forward. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ↑ Bustamante, Cruz (2003). "Recall Information". sos.ca.gov. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ↑ LeDuff, Charlie (September 13, 2003). "G.O.P. Dealing With Split Over 2 Top Contenders". New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Schwarzenegger announces bid for governor". CNN. August 7, 2003. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Recall alphabet: Do you know your RWQs?". CNN. August 12, 2003.

- 1 2 3 Wildermuth, John (August 8, 2003). "Schwarzenegger's GOP rivals quitting / ISSA DROPS OUT: Lawmaker who led recall drive shocks supporters". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ "Top California recall candidates debate -- without Schwarzenegger". CNN. September 3, 2003. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Arnold steals show in California debate". Washington Times. 2003-09-25. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ↑ Schultz, David Andrew (editor). Lights, camera, campaign!: media, politics, and political advertising. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. p. 261. ISBN 0-8204-6831-2.

- ↑ Cal. Elections Code, § 11386.

- ↑ "RECALL QUESTION: Statewide Summary" (PDF). California Secretary of State. 2004-03-11. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- 1 2 "GOVERNOR: Statewide Summary" (PDF). California Secretary of State. 2004-03-11. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ "Report of Registration as of September 22, 2003" (PDF). California Secretary of State. 2003-11-20. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Gathright, Alan (August 24, 2003). "Governor's bid ends for slaying suspect / Silicon Valley man running in recall race linked to a '96 death". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Scott Davis Conviction Upheld". April 28, 2009.

External links

- Davis Recall – Costa's Group

- Rescue California – Issa's Group

- Recall Gray Davis Committee – Kaloogian's Group

- 2003 California Recall Election Web archive at the California Digital Library

Recall information

- Summary of returns

- Statewide Special Election Results

- Recall information from CA Secretary of State

- Gov. Davis Is Recalled; Schwarzenegger Wins

- Recall foes put tactics online. Petition workers complain of intimidation

- Recall Drive Halts Collections. Organizers Say They Have Enough Signatures to Force Vote on Davis

- Davis Recall Qualifies for Fall Ballot

- Davis' Reelection Team Regroups to Fight Recall

- Newspaper article with recall history

- Article 2 of the California state constitution governs initiatives, referenda, and recall

- California Elections Code, ss. 11381–11386 govern the conduct of recall elections