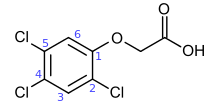

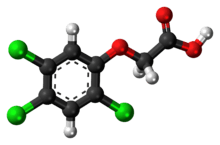

2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic acid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxy)acetic acid | |

| Other names

2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic acid 2,4,5-T Trioxone | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.068 |

| KEGG | |

| RTECS number | AJ8400000 |

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8H5Cl3O3 | |

| Molar mass | 255.48 g/mol |

| Appearance | Off-white to yellow crystalline solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 1.80 g/cm3, 20 °C |

| Melting point | 154 to 158 °C (309 to 316 °F; 427 to 431 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposes[1] |

| 238 mg/kg (30 °C) | |

| Vapor pressure | 1×10−7 mmHg[1] |

| Hazards | |

| R-phrases (outdated) | 22-36/37/38-50/53 |

| S-phrases (outdated) | 24-60-61 |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LD50 (median dose) |

381 mg/kg (guinea pig, oral) 300 mg/kg (rat, oral) 425 mg/kg (hamster, oral) 242 mg/kg (mouse, oral)[2] |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

| PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 10 mg/m3[1] |

| REL (Recommended) |

TWA 10 mg/m3[1] |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) |

250 mg/m3[1] |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

2,4-D auxin |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (also known as 2,4,5-T), a synthetic auxin, is a chlorophenoxy acetic acid herbicide used to defoliate broad-leafed plants. It was developed in the late 1940s and was widely used in the agricultural industry until being phased out, starting in the late 1970s due to toxicity concerns. Agent Orange, a defoliant used by the British in the Malayan Emergency and the U.S. in the Vietnam War, was equal parts 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid). 2,4,5-T itself is toxic with a NOAEL of 3 mg/kg/day and a LOAEL of 10 mg/kg/day.[3] Additionally, the manufacturing process for 2,4,5-T contaminates this chemical with trace amounts of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). TCDD is a carcinogenic persistent organic pollutant with long-term effects on the environment. With proper temperature control during production of 2,4,5-T, TCDD levels can be held to about .005 ppm. Before the TCDD risk was well understood, early production facilities lacked proper temperature controls and individual batches tested later were found to have as much as 60 ppm of TCDD.

In 1970, the United States Department of Agriculture halted the use of 2,4,5-T on all food crops except rice, and in 1985, the EPA terminated all remaining uses in the U.S. of this herbicide. The international trade of 2,4,5-T is restricted by the Rotterdam Convention. 2,4,5-T has since largely been replaced by dicamba and triclopyr.

Human health effects from 2,4,5-T at low environmental doses or at biomonitored levels from low environmental exposures are unknown. Intentional overdoses and unintentional high dose occupational exposures to chlorophenoxy acid herbicides have resulted in weakness, headache, dizziness, nausea, abdominal pain, myotonia, hypotension, renal and hepatic injury, and delayed neuropathy.. Cometabolism of 2,4,5-T is possible to produce 3,5-dichlorocatechol[4] which, in turn, can be degraded by Pseudomona bacteria.[5] IARC considers the chlorophenoxyacetic acids group of chemicals as possibly carcinogenic to humans.[6] In 1963 a production vessel for 2,4,5-T exploded in the Philips-Duphar plant in the Netherlands. Six workers that cleaned up afterwards got seriously intoxicated and developed chloracne. After twelve years, four of the six cleaners had died.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0583". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ "2,4,5-T". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Pamela Sodhy (1991). The US-Malaysian nexus: Themes in superpower-small state relations. Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia. pp. 284–290.

- ↑ Raymond S. Horvath (June 1972), Microbial Co-Metabolism and the Degradation of Organic Compounds in Nature, Bacteriological Reviews, American Society for Microbiology, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 146–155

- ↑ A. M. Chakrabarty (1976), Plasmids in Pseudomonas, Annual Review of Genetics, Vol. 10, pp. 7–30

- ↑ CDC, Biomonitoring Summary

Further reading

- Tschirley FH. Defoliation in Vietnam. Science. 1969;163:779-786.

- Orians GH, Pfeiffer EW. Ecological effects of the war in Vietnam. Science. 1970;168:544-554.

- Neilands JB, Orians GH, Pfeiffer EW, Vennema A, Westing AH. Harvest of Death: Chemical Warfare in Vietnam and Cambodia. New York: Free Press; 1972.

- Gochfeld M. The other victims of the Vietnam war. BioScience. 1975;25:540-541.

- Westing AH, ed. Herbicides in War. The Long Term Ecological and Human Consequences. London: Taylor and Francis; 1984.

- Schecter AJ, Tong HY, Monson SJ, Goss ML. Levels of 2,3,7,8-TCDD in silt samples collected between 1985-86 from rivers in the North and South of Vietnam. Chemosphere. 1989;19:547-550.

- Schecter AJM, Dai LC, Thuy LTB, et al. Agent Orange and the Vietnamese: the persistence of elevated dioxin levels in human tissues. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:516-522.

- Kahn PC, Gochfeld M, Nyugen M, Hansson M, Rappe C, Velez H. Dioxins and dibenzofurans in blood and adipose tissue of Agent Orange-exposed Vietnam veterans and matched controls. JAMA. 1988;259:1661-1667.

- Fingerhut MA, Halperin WE, Marlow DA, et al. Cancer mortality in workers exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:212-218.

External links

- 2,4,5-T - Identification, toxicity, use, water pollution potential, ecological toxicity and regulatory information

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards