1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment

| 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

Flag of the United States, 1867-1877 | |

| Active | 11 November 1864 – 19 July 1867 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Infantry |

| Engagements | Harney Lake Valley[1] |

The 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment was an American Civil War era military regiment recruited in Oregon for the Union Army. The regiment was formed in November 1864. At full strength, it was composed of ten companies of foot soldiers. The regiment was used to guard trade routes and escorted immigrant wagon trains from Fort Boise to the Willamette Valley. Its troops were used to pursue and suppress Indian raiders in eastern Oregon and the Idaho Territory. Several detachments accompanied survey parties and built roads in central and southern Oregon. The regiment's last company was mustered out of service in July 1867.

Background

Following the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, most regular army troops were withdrawn from the Pacific Northwest for service in the war's eastern theatres. This left Oregon and the Washington and Idaho territories without sufficient troops to guard Indian reservations from trespassing miners, escort immigrant wagon trains, and protect settlers and traders from Indian raiders in eastern Oregon and southern Idaho. Oregon officials were also concerned about possible conflicts between pro-Union and pro-Confederate supporters.[2]

As a result, the commander of the United States Army's Department of the Pacific, Brigadier General George Wright asked Oregon Governor John Whiteaker to recruit an Oregon cavalry regiment. At the same time, Wright asked Henry M. McGill, Washington Territory's acting Governor, to raise an infantry regiment in Washington. Both recruiting efforts were successful.[3] The Washington infantry regiment was formed on 18 October 1861, and the 1st Oregon Cavalry was activated a month later on 21 November.[1]

Formation

The initial enlistment period for six of the seven Oregon cavalry companies and five of ten Washington infantry companies expired in the fall of 1864. As a result, Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord, the Army's senior commander in Oregon, asked Oregon's new Governor Addison C. Gibbs to raise a new infantry regiment and recruit backfills for the expected cavalry vacancies. Gibbs agreed, and formally asked Major General Irwin McDowell, who replaced Wright as commander of the Department of the Pacific, to request authority to recruit additional troops for military operations in Oregon. On 31 August 1864, Gibbs and McDowell sent a joint letter to the War Department in Washington, D.C. requesting permission to recruit a new infantry regiment and cavalry replacements. On 20 October 1864, the Governor received a positive reply from the War Department. The news arrived just one day before the end of Oregon's legislative session. Gibbs quickly asked the legislature to provide a $150 enlistment bounty, which the legislators enacted before going home.[3]

Governor Gibbs appointed well known civic leaders as county recruiting officers to give prestige to the effort. The state's pro-union newspapers including The Oregonian, the Oregon Statesman, and the Jacksonville Sentinel all encourage young men to join the new regiment. The publicity along with the $150 bounty helped make the recruiting drive a success.[3] The first companies of the 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment were officially activated on 11 November 1864. By June 1865, the regiment reached ten full-strength companies. Three senior officers from the 1st Oregon Cavalry were promoted and placed in charge of the new infantry regiment. Colonel George B. Currey became the regiment's commander. Lieutenant Colonel John M. Drake was second in command, and Major William V. Rinehart was given the third most senior post.[1]

Operations

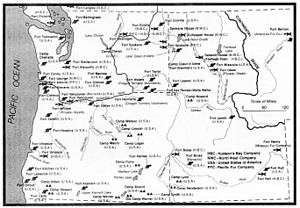

While some detachments of the 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment occasionally skirmished with hostile Indian bands, the regiment's main duties were much more mundane. Most companies spent their time in garrison duty at small posts in eastern Oregon, southeast Washington, and southern Idaho. They protected immigrant trails and escorted wagon trains from Fort Boise to the Willamette Valley. Two companies escorted survey parties, and another constructed a road in southwestern Oregon.[3][4]

While scouting sixteen miles from Camp Wright on the Selvies River, near present-day Burns, Captain Loren L. Williams and a party of twenty Oregon infantrymen from Company H were ambushed by a band of hostile Indians. Williams and his troops fought a harrowing retreat back to Camp Wright, defending themselves for about fifteen hours before they reached safety. All along the way Indians fired from concealed positions. At one point, they even set a brush fire in the soldiers path to prevent them from escaping. Despite their continuous attacks, the Indians only wounded two soldiers. In his report, Williams stated that his long-range rifles killed fifteen Indians. He also stated that his superior weaponry was the only thing that prevented his party from being overrun.[3]

In the summer of 1865, Lieutenant Cyrus H. Walker and the men of Company B were responsible for disarming friendly Indians and guarding numerous wagon trains as they crossed southern Idaho. They also established Camp Reed at Salmon Falls Creek and Camp Wallace at Camas Prairie, both in Idaho. The troops built a blockhouse at Camp Wallace, but later abandoned the site in favor of winter quarters near Fort Hall.[3]

Lieutenant William Grant and his detachment accompanied David P. Thompson and his government survey team through central Oregon as they plotted the Deschutes Meridian, a north-south line extending from the Columbia River to the California border. In another party, Lieutenant John M. McCall led a detachment of forty-eight men responsible for escorting State Surveyor Byron J. Pengra and his assistants as they surveyed the route of the Oregon Central Military Road. The route they surveyed ran from Eugene, Oregon along the Middle Fork of the Willamette River, through the Cascades near Diamond Peak, then across arid southeastern Oregon to Idaho's mining country.[3]

Captain Franklin B. Sprague and twenty men of Company I built a section of road that linked the Rogue River with the John Day road. This connected Jacksonville and southwest Oregon with John Day's mining country. After the construction work was completed, Sprague published a list of the best camp sites along the road in the Jacksonville newspapers so that the wagon masters could find the best water and grass along the way. On 1 August 1865, two hunters from Sprague's party rediscovered Crater Lake, which had been first visited in 1853, but was never effectively recorded so that others could locate the lake. Based on directions from his hunters, Sprague and five other men visited the lake on 12 August. They climbed down the 800 foot caldera cliff to become the first explorers to reach the lake shore. Sprague's account of the visit to "Lake Majestic" was published in the Jacksonville Sentinel on 25 August.[5]

In the fall of 1865, Colonel Currey was planning a winter campaign against the Indians in eastern Oregon. To prepare, he sent detachments of the 1st Oregon Infantry along with Oregon cavalry units to Camp Alvord in the Alvord Valley; Camp Polk near present-day Sisters; Camp Currey near Silver Lake; Camp Logan and Camp Colfax along the Boise Road east of Canyon City; Camp Wallace; and Camp Lander near Fort Hall in the Idaho Territory. Detachment commanders were instructed to build winter quarters at their posts and prepare for a winter offensive. Winter provisions were to follow in supply wagons. However, the end of the Civil War in the east had freed up many regular officers for duty in the west, and as a result, Colonel Currey was released from duty in November 1865 along with the men from companies C, D, and E. Lieutenant Colonel Drake was released from service in December, so the planned winter campaign never got started.[3][6]

Disbanding

The remaining companies spent a long winter in field encampments waiting for orders. In February 1866, Major General Frederick Steele arrived at Fort Vancouver to take command of the Military Department of the Columbia. As soon as the weather improved he ordered the dispersed infantry units, except Captain Sprague's Company I, to report to Fort Vancouver where the volunteers were mustered out of service. Several officers were reassigned to regular Army units arriving from the east, but few were retained more than a year. On 19 July 1867, Captain Sprague, First Lieutenant Harrison B. Oatman, and the men of Company I were the last members of the 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment to be mustered out of the Army.[1][3]

Officers

The following is a list of officers who served in the 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The list was current as of 31 October 1865, the date the first members of the regiment were mustered out of service.[1]

- Colonel - George B. Currey (Commander)

- Lieutenant Colonel - John M. Drake

- Major - William V. Rinehart

- Captains - Charles Lafollett (Commander, Company A); Ephraim Palmer (Commander, Company B); Clark P. Crandall (Commander, Company C); William S. Powell (Commander, Company D); Ferdinand O. McGown (Commander, Company E); Ebner W. Waters (Commander, Company F); Andrew J. Boland (Commander, Company G); Loren L. Williams (Commander, Company H); Franklin B. Sprague (Commander, Company I); and Alphonso B. Ingram (Commander, Company J)

- First Lieutenants - William J. Shipley; Cyrus H. Walker; Thomas H. Reynolds; Samuel F. Kerns; Henry Catley (Quartermaster); John B. Dimick; Darius B. Randall; John L. Boone (Adjutant); William M. Rand; William Grant; Harrison B. Oatman; Byron Barlow

- Second Lieutenants - William R. Dunbar; John W. Cullen; Charles B. Roland; Charles H. Hill; Joseph M. Gale; James A. Balch; Daniel W. Applegate; Peter P. Gates; Charles N. Chapman; and Albert Applegate

- Surgeon - Horace Carpenter; Samuel Whitemore (Assistant Surgeon)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Official Army Register of the Volunteer Forces of the United States Army for the Years 1861, ’62, ’63, ’64, ‘65 (Part VII), Missouri, Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, California, Kansas, Oregon, Nevada., Adjutant General's Office, Secretary of War, Washington, D.C., 2 March 1865.

- ↑ Jette, Melinda, "Broadside, To Arms!", The Oregon History Project, Oregon Historical Society, 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Edwards, Glenn Thomas, Oregon Regiments in the Civil War Years: Duty on the Indian Frontier, unpublished Master of Arts thesis, Department of History, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, June 1960.

- ↑ "Oregon History: Civil War in Oregon", Oregon Blue Book, Oregon State Archives, Officer of the Oregon Secretary of State, Salem, Oregon, 5 November 2008.

- ↑ Greene, Linda, "Captain Franklin B. Sprague", Historic Research Study Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, Cultural Resources Branch, Denver Service Center, National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, Denver, Colorado, June 1984.

- ↑ Carey, Charles Henry, History of Oregon, The Pioneer Historical Publishing Company, Chicago & Portland, Oregon, 1922, pp. 673-74.

External links

- Oregon Blue Book - Civil War History

- Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War - Col. Edward D. Baker Camp

- 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry Civil War reenactors