Hungarian Revolution of 1956

| Hungarian Revolution of 1956 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||

Flag of Hungary, with the communist coat of arms cut out. The flag with a hole became the symbol of the revolution. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

31,550 troops 1,130 tanks[1] Unknown number of government loyalists | Unknown number of soldiers, militia, and armed civilians | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Soviet casualties: 722 killed or missing 1,540 wounded[2] |

2,500–3,000 killed (est.) 13,000 wounded (est.)[3] | ||||||

| 3,000 civilians killed[4] | |||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

By topic |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 or the Hungarian Uprising of 1956[5] (Hungarian: 1956-os forradalom or 1956-os felkelés) was a nationwide revolt against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic and its Soviet-imposed policies, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956. Though leaderless when it first began, it was the first major threat to Soviet control since the USSR's forces drove Nazi Germany from its territory at the end of World War II.

The revolt began as a student demonstration, which attracted thousands as they marched through central Budapest to the Parliament building, calling out on the streets using a van with loudspeakers. A student delegation, entering the radio building to try to broadcast the students' demands, was detained. When the delegation's release was demanded by the demonstrators outside, they were fired upon by the State Security Police (ÁVH) from within the building. One student died and was wrapped in a flag and held above the crowd. This was the start of the revolution. As the news spread, disorder and violence erupted throughout the capital.

The revolt spread quickly across Hungary and the government collapsed. Thousands organised into militias, battling the ÁVH and Soviet troops. Pro-Soviet communists and ÁVH members were often executed or imprisoned and former political prisoners were released and armed. Radical impromptu workers' councils wrested municipal control from the ruling Hungarian Working People's Party and demanded political changes. A new government formally disbanded the ÁVH, declared its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact, and pledged to re-establish free elections. By the end of October, fighting had almost stopped and a sense of normality began to return.

After announcing a willingness to negotiate a withdrawal of Soviet forces, the Politburo changed its mind and moved to crush the revolution. On 4 November, a large Soviet force invaded Budapest and other regions of the country. The Hungarian resistance continued until 10 November. Over 2,500 Hungarians and 700 Soviet troops were killed in the conflict, and 200,000 Hungarians fled as refugees. Mass arrests and denunciations continued for months thereafter. By January 1957, the new Soviet-installed government had suppressed all public opposition. These Soviet actions, while strengthening control over the Eastern Bloc, alienated many Western Marxists, leading to splits and/or considerable losses of membership for communist parties in capitalist states.

Public discussion about this revolution was suppressed in Hungary for more than 30 years. Since the thaw of the 1980s, it has been a subject of intense study and debate. At the inauguration of the Third Hungarian Republic in 1989, 23 October was declared a national holiday.

Prelude

During World War II Hungary was a member of the Axis powers, allied with the forces of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Romania, and Bulgaria. In 1941, the Hungarian military participated in the occupation of Yugoslavia and the invasion of the Soviet Union. The Red Army was able to force back the Hungarian and other Axis invaders, and by 1944 was advancing towards Hungary.

Fearing invasion, the Hungarian government began armistice negotiations with the Allies. These ended when Nazi Germany invaded and occupied the country and set up the pro-Axis Government of National Unity.

Both Hungarian and German forces stationed in Hungary were subsequently defeated when the Soviet Union invaded the country in 1945.

Postwar occupation

Towards the end of World War II, the Soviet Army occupied Hungary, with the country coming under the Soviet Union's sphere of influence. Immediately after World War II, Hungary was a multiparty democracy, and elections in 1945 produced a coalition government under Prime Minister Zoltán Tildy. However, the Hungarian Communist Party, a Marxist–Leninist group who shared the Soviet government's ideological beliefs, constantly wrested small concessions in a process named salami tactics, which sliced away the elected government's influence, despite the fact that it had received only 17% of the vote.[6][7]

After the elections of 1945, the portfolio of the Interior Ministry, which oversaw the Hungarian State Security Police (Államvédelmi Hatóság, later known as the ÁVH), was transferred from the Independent Smallholders Party to a nominee of the Communist Party.[8] The ÁVH employed methods of intimidation, falsified accusations, imprisonment, and torture to suppress political opposition.[9] The brief period of multi-party democracy came to an end when the Communist Party merged with the Social Democratic Party to become the Hungarian Working People's Party, which stood its candidate list unopposed in 1949. The People's Republic of Hungary was then declared.[7]

The Hungarian Working People's Party set about to modify the economy into socialism by undertaking radical nationalization based on the Soviet model. This forced method of economic socialisation during infrastructural recovery from the war initially resulted in economic stagnation, lower standards of living, and a deep malaise. Writers and journalists were the first to voice open criticism of the government and its policies, publishing critical articles in 1955.[10] By 22 October 1956, Technical University students had resurrected the banned MEFESZ student union,[11] and staged a demonstration on 23 October that set off a chain of events leading directly to the revolution.

Political repression and economic decline

Hungary became a communist state under the authoritarian leadership of Mátyás Rákosi.[12] Under Rákosi's reign, the Security Police (ÁVH) began a series of purges, first within the Communist Party to end opposition to Rákosi's reign. The victims were labeled as "Titoists," "western agents," or "Trotskyists" for as insignificant a crime as spending time in the West to participate in the Spanish Civil War. In total, about half of all the middle and lower level party officials—at least 7,000 people—were purged.[13][14][15]

From 1950 to 1952, the Security Police forcibly relocated thousands of people to obtain property and housing for the Working People's Party members, and to remove the threat of the intellectual and 'bourgeois' class. Thousands were arrested, tortured, tried, and imprisoned in concentration camps, deported to the east, or were executed, including ÁVH founder László Rajk.[14][16] In a single year, more than 26,000 people were forcibly relocated from Budapest. As a consequence, jobs and housing were very difficult to obtain. The deportees generally experienced terrible living conditions and were interned as slave labor on collective farms. Many died as a result of poor living conditions and malnutrition.[15]

The Rákosi government thoroughly politicised Hungary's educational system to supplant the educated classes with a "toiling intelligentsia".[17] Russian language study and Communist political instruction were made mandatory in schools and universities nationwide. Religious schools were nationalized and church leaders were replaced by those loyal to the government.[18] In 1949 the leader of the Hungarian Catholic Church, Cardinal József Mindszenty, was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment for treason.[19] Under Rákosi, Hungary's government was among the most repressive in Europe.[7][16]

The post-war Hungarian economy suffered from multiple challenges. Hungary agreed to pay war reparations approximating US$300 million to the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia and to support Soviet garrisons.[20] The Hungarian National Bank in 1946 estimated the cost of reparations as "between 19 and 22 per cent of the annual national income."[21] In 1946, the Hungarian currency experienced marked depreciation, resulting in the highest historic rates of hyperinflation known.[22] Hungary's participation in the Soviet-sponsored COMECON (Council Of Mutual Economic Assistance) prevented it from trading with the West or receiving Marshall Plan aid.[23]

In addition, Rákosi began his first Five-Year Plan in 1950-based on Joseph Stalin's industrial program of the same name that sought to raise industrial output by 380 percent.[13] Like its Soviet counterpart, the Five-Year Plan never achieved these outlandish goals due in part to the crippling effect of the exportation of most of Hungary's raw resources and technology to the Soviet Union as well as Rákosi's purges of much of the former professional class. In fact, the Five-Year Plan weakened Hungary's existing industrial structure and caused real industrial wages to fall by 18 percent between 1949 and 1952.[13] Rákosi's agricultural programs met with the same lack of success, with attempted collectivization of the peasantry causing a marked fall in agricultural output and a rise in food shortages.

Although national income per capita rose in the first third of the 1950s, the standard of living fell. Huge income deductions to finance industrial investment reduced disposable personal income; mismanagement created chronic shortages in basic foodstuffs resulting in rationing of bread, sugar, flour, and meat.[24] Compulsory subscriptions to state bonds further reduced personal income. The net result was that disposable real income of workers and employees in 1952 was only two-thirds of what it had been in 1938, whereas in 1949, the proportion had been 90%.[25] These policies had a cumulative negative effect and fueled discontent as foreign debt grew and the population experienced shortages of goods.[26]

International events

On 5 March 1953, Joseph Stalin died, ushering in a period of moderate liberalization, when most European communist parties developed a reform wing. In Hungary, the reformist Imre Nagy replaced Rákosi, "Stalin's Best Hungarian Disciple", as Prime Minister.[27] However, Rákosi remained General Secretary of the Party, and was able to undermine most of Nagy's reforms. By April 1955, he had Nagy discredited and removed from office.[28] After Khrushchev's "secret speech" of February 1956, which denounced Stalin and his protégés,[29] Rákosi was deposed as General Secretary of the Party and replaced by Ernő Gerő on 18 July 1956.[30] Radio Free Europe would broadcast the "secret speech" to Eastern Europe on the advice of Ray S. Cline, who saw it as a way to "as I think I told [Allen Dulles] to say, 'indict the whole Soviet system'." [31]

On 14 May 1955, the Soviet Union created the Warsaw Pact, binding Hungary to the Soviet Union and its satellite states in Central and Eastern Europe. Among the principles of this alliance were "respect for the independence and sovereignty of states" and "non-interference in their internal affairs".[32]

In 1955, the Austrian State Treaty and ensuing declaration of neutrality established Austria as a demilitarised and neutral country.[33] This raised Hungarian hopes of also becoming neutral and in 1955 Nagy had considered "... the possibility of Hungary adopting a neutral status on the Austrian pattern".[34]

In June 1956, a violent uprising by Polish workers in Poznań was put down by the government, with scores of protesters killed and wounded. Responding to popular demand, in October 1956, the government appointed the recently rehabilitated reformist communist Władysław Gomułka as First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party, with a mandate to negotiate trade concessions and troop reductions with the Soviet government. After a few tense days of negotiations, on 19 October the Soviets finally gave in to Gomułka's reformist demands.[35] News of the concessions won by the Poles, known as Polish October, emboldened many Hungarians to hope for similar concessions for Hungary and these sentiments contributed significantly to the highly charged political climate that prevailed in Hungary in the second half of October 1956.[36]

Within the Cold War context of the time, by 1956, a fundamental tension had appeared in US policy towards Hungary and the Eastern Bloc generally. The United States hoped to encourage European countries to break away from the bloc through their own efforts but wanted to avoid a US-Soviet military confrontation, as escalation might lead to nuclear war. For these reasons, US policy makers had to consider other means of diminishing Soviet influence in Eastern Europe, short of a rollback policy. This led to the development of containment policies such as economic and psychological warfare, covert operations, and, later, negotiation with the Soviet Union regarding the status of the Eastern states.[37] Vice President Richard Nixon had also argued to the National Security Council that it would serve US interests if the Soviet Union would turn on another uprising as they had in Poland, providing a source of anti-Communist propaganda.[38] However, while CIA director Allen Dulles had claimed he was creating an extensive network in Hungary, at the time the agency had no Hungarian station, almost no agents who spoke the language, and unreliable, corrupt local assets. The agency's own secret history would admit "at no time did we have anything that could or should have been mistaken for an intelligence operation".[39]

In the summer of 1956, relations between Hungary and the US began to improve. At that time, the US responded very favourably to Hungary's overtures about a possible expansion of bilateral trade relations. Hungary's desire for better relations was partly attributable to the country's catastrophic economic situation. Before any results could be achieved, however, the pace of negotiations was slowed by the Hungarian Ministry of Internal Affairs, which feared that better relations with the West might weaken Communist rule in Hungary.[37]

Social unrest builds

Rákosi's resignation in July 1956 emboldened students, writers, and journalists to be more active and critical in politics. Students and journalists started a series of intellectual forums examining the problems facing Hungary. These forums, called Petőfi circles, became very popular and attracted thousands of participants.[40] On 6 October 1956, László Rajk, who had been executed by the Rákosi government, was reburied in a moving ceremony that strengthened the party opposition.[41]

On 16 October 1956, university students in Szeged snubbed the official communist student union, the DISZ, by re-establishing the MEFESZ (Union of Hungarian University and Academy Students), a democratic student organization, previously banned under the Rákosi dictatorship.[11] Within days, the student bodies of Pécs, Miskolc, and Sopron followed suit. On 22 October, students of the Technical University compiled a list of sixteen points containing several national policy demands.[42] After the students heard that the Hungarian Writers' Union planned on the following day to express solidarity with pro-reform movements in Poland by laying a wreath at the statue of Polish-born General Bem, a hero of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 (1848–49), the students decided to organize a parallel demonstration of sympathy.[36][43]

Revolution

First shots

On the afternoon of 23 October 1956, approximately 20,000 protesters convened next to the statue of József Bem—a national hero of Poland and Hungary.[44] Péter Veres, President of the Writers' Union, read a manifesto to the crowd, which included: The desire for Hungary to be independent from all foreign powers; a political system based on democratic socialism (land reform and public ownership of businesses); Hungary joining the United Nations; and citizens of Hungary should have all the rights of free men.[45] After the students read their proclamation, the crowd chanted a censored patriotic poem the "National Song", with the refrain: "This we swear, this we swear, that we will no longer be slaves." Someone in the crowd cut out the Communist coat of arms from the Hungarian flag, leaving a distinctive hole, and others quickly followed suit.[46] Afterwards, most of the crowd crossed the River Danube to join demonstrators outside the Parliament Building. By 18:00, the multitude had swollen to more than 200,000 people;[47] the demonstration was spirited, but peaceful.[48]

At 20:00, First Secretary Ernő Gerő broadcast a speech condemning the writers' and students' demands.[48] Angered by Gerő's hard-line rejection, some demonstrators decided to carry out one of their demands, the removal of Stalin's 30-foot-high (9.1 m) bronze statue that was erected in 1951 on the site of a church, which was demolished to make room for the monument.[49] By 21:30, the statue was toppled and crowds celebrated by placing Hungarian flags in Stalin's boots, which was all that was left of the statue.[48]

At about the same time, a large crowd gathered at the Radio Budapest building, which was heavily guarded by the ÁVH. The flash point was reached as a delegation attempting to broadcast their demands was detained and the crowd grew increasingly unruly as rumours spread that the protesters had been shot. Tear gas was thrown from the upper windows and the ÁVH opened fire on the crowd, killing many.[50] The ÁVH tried to re-supply itself by hiding arms inside an ambulance, but the crowd detected the ruse and intercepted it. Hungarian soldiers sent to relieve the ÁVH hesitated and then, tearing the red stars from their caps, sided with the crowd.[46][50] Provoked by the ÁVH attack, protesters reacted violently. Police cars were set ablaze, guns were seized from military depots and distributed to the masses and symbols of the Communist regime were vandalised.[51]

Fighting spreads, government falls

During the night of 23 October, Hungarian Working People's Party Secretary Ernő Gerő requested Soviet military intervention "to suppress a demonstration that was reaching an ever greater and unprecedented scale."[35] The Soviet leadership had formulated contingency plans for intervention in Hungary several months before.[52] By 02:00 on 24 October, acting in accordance with orders of Georgy Zhukov, the Soviet defence minister, Soviet tanks entered Budapest.[53]

By noon, on 24 October, Soviet tanks were stationed outside the Parliament, and Soviet soldiers guarded key bridges and crossroads. Armed revolutionaries quickly set up barricades to defend Budapest, and were reported to have already captured some Soviet tanks by mid-morning.[46] That day, Imre Nagy replaced András Hegedüs as Prime Minister.[54] On the radio, Nagy called for an end to violence and promised to initiate political reforms that had been shelved three years earlier. The population continued to arm itself as sporadic violence erupted.[55]

Armed protesters seized the radio building. At the offices of the Communist newspaper Szabad Nép unarmed demonstrators were fired upon by ÁVH guards who were then driven out as armed demonstrators arrived.[55] At this point, the revolutionaries' wrath focused on the ÁVH;[56] Soviet military units were not yet fully engaged, and there were reports of some Soviet troops showing open sympathy for the demonstrators.[57]

On 25 October, a mass of protesters gathered in front of the Parliament Building. ÁVH units began shooting into the crowd from the rooftops of neighbouring buildings.[58][59] Some Soviet soldiers returned fire on the ÁVH, mistakenly believing that they were the targets of the shooting.[46][60] Supplied by arms taken from the ÁVH or given by Hungarian soldiers who joined the uprising, some in the crowd started shooting back.[46][58]

During this time, the Hungarian Army was divided as the central command structure disintegrated with the rising pressures from the protests on the government. The majority of Hungarian military units in Budapest and the countryside remained uninvolved, as the local commanders generally avoided using force against the protesters and revolutionaries.[61] From 24 to 29 October, however, there were 71 cases of armed clashes between the army and the populace in fifty communities, ranging from the defence of attacks on civilian and military objectives to fighting with insurgents depending on the commanding officer.[61]

One example is in the town of Kecskemét on 26 October, where demonstrations in front of the office of State Security and the local jail led to military action by the Third Corps under the orders of Major General Lajos Gyurkó, in which seven protesters were shot and several of the organizers were arrested. In another case, a fighter jet strafed a protest in the town of Tiszakécske, killing 17 people and wounding 117.[61]

The attacks at the Parliament forced the collapse of the government.[62] Communist First Secretary Ernő Gerő and former Prime Minister András Hegedüs fled to the Soviet Union; Imre Nagy became Prime Minister and János Kádár First Secretary of the Communist Party.[63] Revolutionaries began an aggressive offensive against Soviet troops and the remnants of the ÁVH.

_t%C3%A9r%2C_a_p%C3%A1rth%C3%A1z_ostromakor_kiv%C3%A9gzett_v%C3%A9d%C5%91_holtteste._Fortepan_24462.jpg)

Units led by Béla Király, after attacking the building of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, executed dozens of suspected communists, state security members, and military personnel. Photographs showed victims with signs of torture. On 30 October, Király's forces attacked the Central Committee of the Communist Party building.[64] Hungarian politician János Berecz referred to how rebels detained thousands of people, and that thousands more had their names on death lists. In the city of Kaposvár, 64 persons including 13 army officers were detained on 31 October.[65]

In Budapest and other areas, the Hungarian Communist committees organised defence. At the Csepel neighbourhood of Budapest, some 250 Communists defended the Csepel Iron and Steel Works. On 27 October, army units were brought in to secure Csepel and restore order. They later withdrew on 29 October, after which the rebels seized control of the area. Communists of Budapest neighbourhood Angyalföld led more than 350 armed workers and 380 servicemen from the Láng Factory. Anti-fascist resistance veterans from World War II participated in the offensive by which the Szabad Nép newspaper's building was recaptured. In the countryside, defence measures were taken by pro-Communist forces. In Békés County, in and around the town of Szarvas, the armed guards of the Communist Party were in control throughout.[66]

As the Hungarian resistance fought Soviet tanks using Molotov cocktails in the narrow streets of Budapest, revolutionary councils arose nationwide, assumed local governmental authority, and called for general strikes. Public Communist symbols such as red stars and Soviet war memorials were removed, and Communist books were burned. Spontaneous revolutionary militias arose, such as the 400-man group loosely led by József Dudás, which attacked or murdered Soviet sympathisers and ÁVH members.[67] Soviet units fought primarily in Budapest; elsewhere the countryside was largely quiet. One armoured division stationed in Budapest, commanded by Pál Maléter, instead opted to join the insurgents. Soviet commanders often negotiated local cease-fires with the revolutionaries.[68]

In some regions, Soviet forces managed to quell revolutionary activity. In Budapest, the Soviets were eventually fought to a stand-still and hostilities began to wane. Hungarian general Béla Király, freed from a life sentence for political offences and acting with the support of the Nagy government, sought to restore order by unifying elements of the police, army and insurgent groups into a National Guard.[69] A ceasefire was arranged on 28 October, and by 30 October most Soviet troops had withdrawn from Budapest to garrisons in the Hungarian countryside.[70]

Interlude

Fighting ceased between 28 October and 4 November, as many Hungarians believed that Soviet military units were withdrawing from Hungary.[71] There were approximately 213 Hungarian Working People's Party members lynched or executed during this period.[72]

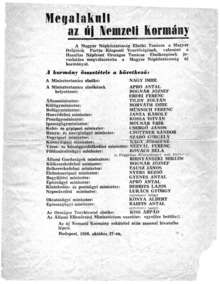

New Government

The rapid spread of the uprising in the streets of Budapest and the abrupt fall of the Gerő-Hegedüs government left the new national leadership surprised, and at first disorganised. Nagy, a loyal party reformer described as possessing "only modest political skills",[73] initially appealed to the public for calm and a return to the old order. Yet Nagy, the only remaining Hungarian leader with credibility in both the eyes of the public and the Soviets, "at long last concluded that a popular uprising rather than a counter-revolution was taking place".[74] At 13:20 on 28 October, Nagy announced an immediate and general cease-fire over the radio and, on behalf of the new national government, declared the following:

- that the government would assess the uprising not as counter-revolutionary but as a "great, national and democratic event"

- an unconditional general ceasefire and amnesty for those who participated in the uprising; negotiations with the insurgents

- the dissolution of the ÁVH

- the establishment of a national guard

- the immediate withdrawal of Soviet troops from Budapest and negotiations for the withdrawal of all Soviet forces from Hungary

On 1 November, in a radio address to the Hungarian people, Nagy formally declared Hungary's withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact as well as Hungary's stance of neutrality.[61][75][76] Because it held office only ten days, the National Government had little chance to clarify its policies in detail. However, newspaper editorials at the time stressed that Hungary should be a neutral, multi-party social democracy.[77] Many political prisoners were released, most notably Cardinal József Mindszenty.[78] Political parties that were previously banned, such as the Independent Smallholders and the National Peasant Party (under the name "Petőfi Party"),[79] reappeared to join the coalition.[80]

_k%C3%B6r%C3%BAt_sarok._Fortepan_23591.jpg)

During this time, in 1,170 communities across Hungary there were 348 cases in which revolutionary councils and protesters dismissed employees of the local administrative councils, 312 cases in which they sacked the persons in charge, and 215 cases in which they burned the local administrative files and records. In addition, in 681 communities demonstrators damaged symbols of Soviet authority such as red stars, Stalin or Lenin statues; 393 in which they damaged Soviet war memorials, and 122 communities in which book burnings took place.[13][61]

Local revolutionary councils formed throughout Hungary,[81][82][83][84] generally without involvement from the preoccupied National Government in Budapest, and assumed various responsibilities of local government from the defunct Communist party.[85] By 30 October, these councils had been officially sanctioned by the Hungarian Working People's Party, and the Nagy government asked for their support as "autonomous, democratic local organs formed during the Revolution".[85] Likewise, workers' councils were established at industrial plants and mines, and many unpopular regulations such as production norms were eliminated. The workers' councils strove to manage the enterprise while protecting workers' interests, thus establishing a socialist economy free of rigid party control.[86] Local control by the councils was not always bloodless; in Debrecen, Győr, Sopron, Mosonmagyaróvár and other cities, crowds of demonstrators were fired upon by the ÁVH, with many lives lost. The ÁVH were disarmed, often by force, in many cases assisted by the local police.[85]

In total there were approximately 2,100 local revolutionary and workers councils with over 28,000 members. These councils held a combined conference in Budapest, deciding to end the nationwide labour strikes and resume work on 5 November, with the more important councils sending delegates to the Parliament to assure the Nagy government of their support.[61]

Soviet perspective

On 24 October, the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (the Politburo) discussed the political upheavals in Poland and Hungary. A hard-line faction led by Molotov was pushing for intervention, but Khrushchev and Marshal Zhukov were initially opposed. A delegation in Budapest reported that the situation was not as dire as had been portrayed. Khrushchev stated that he believed that Party Secretary Ernő Gerő's request for intervention on 23 October indicated that the Hungarian Party still held the confidence of the Hungarian public. In addition, he saw the protests not as an ideological struggle, but as popular discontent over unresolved basic economic and social issues.[35] The concurrent Suez Crisis was another reason to not intervene; as Khrushchev said on 28 October, it would be a mistake to imitate the "real mess" of the French and British.[87]

After some debate,[88][89] the Presidium on 30 October decided not to remove the new Hungarian government. Even Marshal Georgy Zhukov said: "We should withdraw troops from Budapest, and if necessary withdraw from Hungary as a whole. This is a lesson for us in the military-political sphere." They adopted a Declaration of the Government of the USSR on the Principles of Development and Further Strengthening of Friendship and Cooperation between the Soviet Union and other Socialist States, which was issued the next day. This document proclaimed: "The Soviet Government is prepared to enter into the appropriate negotiations with the government of the Hungarian People's Republic and other members of the Warsaw Treaty on the question of the presence of Soviet troops on the territory of Hungary."[90] Thus for a brief moment it looked like there could be a peaceful solution.

_t%C3%A9r%2C_MDP_Budapesti_P%C3%A1rtbizotts%C3%A1g%C3%A1nak_sz%C3%A9kh%C3%A1za._Fortepan_24495.jpg)

On 30 October, armed protesters attacked the ÁVH detachment guarding the Budapest Hungarian Working People's Party headquarters on Köztársaság tér (Republic Square), incited by rumours of prisoners held there and the earlier shootings of demonstrators by the ÁVH in the city of Mosonmagyaróvár.[85][91][92] Over 20 ÁVH officers were killed, some of them lynched by the mob. Hungarian army tanks sent to rescue the party headquarters mistakenly bombarded the building.[92] The head of the Budapest party committee, Imre Mező, was wounded and later died.[93][94] Scenes from Republic Square were shown on Soviet newsreels a few hours later.[95] Revolutionary leaders in Hungary condemned the incident and appealed for calm, and the mob violence soon died down,[96] but images of the victims were nevertheless used as propaganda by various Communist organs.[94]

On 31 October the Soviet leaders decided to reverse their decision from the previous day. There is disagreement among historians whether Hungary's declaration to exit the Warsaw Pact caused the second Soviet intervention. Minutes of 31 October meeting of the Presidium record that the decision to intervene militarily was taken one day before Hungary declared its neutrality and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact.[97] Historians who deny that Hungarian neutrality—or other factors such as Western inaction in Hungary or perceived Western weakness due to the Suez crisis—caused the intervention state that the Soviet decision was based solely on the rapid loss of Communist control in Hungary.[87] However, some Russian historians who are not advocates of the Communist era maintain that the Hungarian declaration of neutrality caused the Kremlin to intervene a second time.[98]

Two days earlier, on 30 October, when Soviet Politburo representatives Anastas Mikoyan and Mikhail Suslov were in Budapest, Nagy had hinted that neutrality was a long-term objective for Hungary, and that he was hoping to discuss this matter with the leaders in the Kremlin. This information was passed on to Moscow by Mikoyan and Suslov.[99][100] At that time, Khrushchev was in Stalin's dacha, considering his options regarding Hungary. One of his speech writers later said that the declaration of neutrality was an important factor in his subsequent decision to support intervention.[101] In addition, some Hungarian leaders of the revolution as well as students had called for their country's withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact much earlier, and this may have influenced Soviet decision making.[102]

Several other key events alarmed the Presidium and cemented the interventionists' position:[103][104]

- Simultaneous movements towards multi-party parliamentary democracy, and a democratic national council of workers, which could "lead towards a capitalist state." Both movements challenged the pre-eminence of the Soviet Communist Party in Eastern Europe and perhaps Soviet hegemony itself. Hannah Arendt considered the councils "the only free and acting soviets (councils) in existence anywhere in the world".[105][106]

- Khrushchev stated that many in the Communist Party would not understand a failure to respond with force in Hungary. Destalinisation had alienated the more conservative elements of the Party, who were alarmed at threats to Soviet influence in Eastern Europe. On 17 June 1953, workers in East Berlin had staged an uprising, demanding the resignation of the government of the German Democratic Republic. This was quickly and violently put down with the help of the Soviet military, with 84 killed and wounded and 700 arrested.[107] In June 1956, in Poznań, Poland, an anti-government workers' revolt had been suppressed by the Polish security forces with between 57[108] and 78[109][110] deaths and led to the installation of a less Soviet-controlled government. Additionally, by late October, unrest was noticed in some regional areas of the Soviet Union: while this unrest was minor, it was intolerable.

- Hungarian neutrality and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact represented a breach in the Soviet defensive buffer zone of satellite nations.[111] Soviet fear of invasion from the West made a defensive buffer of allied states in Eastern Europe an essential security objective.

_utca_fel%C5%91l_a_Honv%C3%A9d_utca_fel%C3%A9_n%C3%A9zve._A_szovjet_csapatok_ideiglenes_kivonul%C3%A1sa_1956._okt%C3%B3ber_31-%C3%A9n._Fortepan_24787.jpg)

In the light of what was taking place in China and the news from Budapest, these militants arrived at the conclusion that "the Party is the incarnation of bureaucratic despotism" and that "socialism can develop only on the foundations of direct democracy". For them the struggle of the Hungarian workers was a struggle "for the principle of direct democracy" and "all power should be transferred to the Workers Committees of Hungary".[112] The Presidium decided to break the de facto ceasefire and crush the Hungarian revolution.[113] The plan was to declare a "Provisional Revolutionary Government" under János Kádár, who would appeal for Soviet assistance to restore order. According to witnesses, Kádár was in Moscow in early November,[114] and he was in contact with the Soviet embassy while still a member of the Nagy government.[115] Delegations were sent to other Communist governments in Eastern Europe and China, seeking to avoid a regional conflict, and propaganda messages prepared for broadcast when the second Soviet intervention had begun. To disguise these intentions, Soviet diplomats were to engage the Nagy government in talks discussing the withdrawal of Soviet forces.[97]

According to some sources, the Chinese leader Mao Zedong played an important role in Khrushchev's decision to suppress the Hungarian uprising. Chinese Communist Party Deputy Chairman Liu Shaoqi pressured Khrushchev to send in troops to put down the revolt by force.[116][117] Although the relations between China and the Soviet Union had deteriorated during the recent years, Mao's words still carried great weight in the Kremlin, and they were frequently in contact during the crisis. Initially, Mao opposed a second intervention, and this information was passed on to Khrushchev on 30 October, before the Presidium met and decided against intervention.[118] Mao then changed his mind in favour of intervention but, according to William Taubman, it remains unclear when and how Khrushchev learned of this and thus if it influenced his decision on 31 October.[119]

From 1 to 3 November, Khrushchev left Moscow to meet with his European allies and inform them of the decision to intervene. At the first such meeting, he met with Władysław Gomułka in Brest. Then, he had talks with the Romanian, Czechoslovak, and Bulgarian leaders in Bucharest. Finally Khrushchev flew with Malenkov to Yugoslavia, where they met with Josip Broz Tito, who was on holiday on his island Brioni in the Adriatic. The Yugoslavs also persuaded Khrushchev to choose János Kádár instead of Ferenc Münnich as the new leader of Hungary.[120][121] Two months after the Soviet crackdown, Tito confided in Nikolai Firiubin, the Soviet ambassador to Yugoslavia, that "the reaction raised its head, especially in Croatia, where the reactionary elements openly incited the employees of the Yugoslav security organs to violence."[122]

International reaction

Although John Foster Dulles, the United States Secretary of State recommended on 24 October for the United Nations Security Council to convene to discuss the situation in Hungary, little immediate action was taken to introduce a resolution,[123] in part because other world events unfolded the day after the peaceful interlude started, when allied collusion started the Suez Crisis. The problem was not that Suez distracted US attention from Hungary but that it made the condemnation of Soviet actions very difficult. As Vice President Richard Nixon later explained, "We couldn't on one hand, complain about the Soviets intervening in Hungary and, on the other hand, approve of the British and the French picking that particular time to intervene against [Gamel Abdel] Nasser".[37]

The US response was reliant on the CIA to covertly effect change, with both covert agents and Radio Free Europe. However, their Hungarian operations collapsed rapidly and they could not locate any of the weapon caches hidden across Europe, nor be sure who they'd send arms too. The agency's main source of information were the newspapers and a State Department employee in Budapest called Geza Katona.[39] By 28 October, on the same night that the new Nagy government came to power, RFE was ramping up its broadcasts—encouraging armed struggle, advising on how to combat tanks and signing off with "Freedom or Death!"—on the orders of Frank Wisner. When Nagy did come to power, CIA director Allen Dulles advised the White House that Cardinal Mindszenty would be a better leader (due to Nagy's communist past); he had CIA radio broadcasts run propaganda against Nagy, calling him a traitor who'd invited Soviet troops in. Broadcasts continued to broadcast armed response while the CIA mistakenly believed that the Hungarian army was switching sides and the rebels were gaining arms.[124] (Wisner was recorded as having a "nervous breakdown" by William Colby as the uprising was crushed[125])

Responding to the plea by Nagy at the time of the second massive Soviet intervention on 4 November, the Security Council resolution critical of Soviet actions was vetoed by the Soviet Union; instead resolution 120 was adopted to pass the matter onto the General Assembly. The General Assembly, by a vote of 50 in favour, 8 against and 15 abstentions, called on the Soviet Union to end its Hungarian intervention, but the newly constituted Kádár government rejected UN observers.[126]

US President Dwight D. Eisenhower was aware of a detailed study of Hungarian resistance that recommended against US military intervention,[127] and of earlier policy discussions within the National Security Council that focused upon encouraging discontent in Soviet satellite nations only by economic policies and political rhetoric.[37][128] In a 1998 interview, Hungarian Ambassador Géza Jeszenszky was critical of Western inaction in 1956, citing the influence of the United Nations at that time and giving the example of UN intervention in Korea from 1950 to 1953.[129]

During the uprising, the Radio Free Europe (RFE) Hungarian-language programs broadcast news of the political and military situation, as well as appealing to Hungarians to fight the Soviet forces, including tactical advice on resistance methods. After the Soviet suppression of the revolution, RFE was criticised for having misled the Hungarian people that NATO or United Nations would intervene if citizens continued to resist.[130] Allen Dulles lied to Eisenhower that RFE had not promised US aid; Eisenhower believed him, as the transcripts of the broadcasts were kept secret.[124]

Soviet intervention of 4 November

On 1 November, Imre Nagy received reports that Soviet forces had entered Hungary from the east and were moving towards Budapest.[131] Nagy sought and received assurances (which proved false) from Soviet ambassador Yuri Andropov that the Soviet Union would not invade. The Cabinet, with János Kádár in agreement, declared Hungary's neutrality, withdrew from the Warsaw Pact, and requested assistance from the diplomatic corps in Budapest and the UN Secretary-General to defend Hungary's neutrality.[132] Ambassador Andropov was asked to inform his government that Hungary would begin negotiations on the removal of Soviet forces immediately.[133][134]

On 3 November, a Hungarian delegation led by the Minister of Defense Pál Maléter were invited to attend negotiations on Soviet withdrawal at the Soviet Military Command at Tököl, near Budapest. At around midnight that evening, General Ivan Serov, Chief of the Soviet Security Police (KGB) ordered the arrest of the Hungarian delegation,[135] and the next day, the Soviet army again attacked Budapest.[136]

During the early morning hours of 4 November, Ferenc Münnich announced on Radio Szolnok the establishment of the "Revolutionary Workers'-Peasants' Government of Hungary".

The second Soviet intervention, codenamed "Operation Whirlwind", was launched by Marshal Ivan Konev.[104][137] The five Soviet divisions stationed in Hungary before 23 October were augmented to a total strength of 17 divisions.[138] The 8th Mechanized Army under command of Lieutenant General Hamazasp Babadzhanian and the 38th Army under Lieutenant General Hadzhi-Umar Mamsurovs from the nearby Carpathian Military District were deployed to Hungary for the operation.[139] Some rank-and-file Soviet soldiers reportedly believed they were being sent to Berlin to fight German fascists.[140] By 21:30 on 3 November, the Soviet Army had completely encircled Budapest.[141]

At 03:00 on 4 November, Soviet tanks penetrated Budapest along the Pest side of the Danube in two thrusts: one up the Soroksári road from the south and the other down the Váci road from the north. Thus before a single shot was fired, the Soviets had effectively split the city in half, controlled all bridgeheads, and were shielded to the rear by the wide Danube river. Armoured units crossed into Buda and at 04:25 fired the first shots at the army barracks on Budaörsi Road. Soon after, Soviet artillery and tank fire was heard in all districts of Budapest.[141] Operation Whirlwind combined air strikes, artillery, and the co-ordinated tank-infantry action of 17 divisions.[142]

_k%C3%B6zn%C3%A9l._Harck%C3%A9ptelenn%C3%A9_tett_ISU-152-es_szovjet_rohaml%C3%B6vegek%2C_a_h%C3%A1tt%C3%A9rben_egy_T-34-85_harckocsi._Fortepan_24854.jpg)

Between 4 and 9 November, the Hungarian Army put up sporadic and disorganised resistance, with Marshal Zhukov reporting the disarming of twelve divisions, two armoured regiments, and the entire Hungarian Air Force. The Hungarian Army continued its most formidable resistance in various districts of Budapest and in and around the city of Pécs in the Mecsek Mountains, and in the industrial centre of Dunaújváros (then called Stalintown). Fighting in Budapest consisted of between ten and fifteen thousand resistance fighters, with the heaviest fighting occurring in the working-class stronghold of Csepel on the Danube River.[143] Although some very senior officers were openly pro-Soviet, the rank and file soldiers were overwhelmingly loyal to the revolution and either fought against the invasion or deserted. The United Nations reported that there were no recorded incidents of Hungarian Army units fighting on the side of the Soviets.[144]

At 05:20 on 4 November, Imre Nagy broadcast his final plea to the nation and the world, announcing that Soviet Forces were attacking Budapest and that the Government remained at its post.[145] The radio station, Free Kossuth Rádió, stopped broadcasting at 08:07.[146] An emergency Cabinet meeting was held in the Parliament but was attended by only three ministers. As Soviet troops arrived to occupy the building, a negotiated evacuation ensued, leaving Minister of State István Bibó as the last representative of the National Government remaining at his post.[147] He wrote For Freedom and Truth, a stirring proclamation to the nation and the world.[148]

_k%C3%B6r%C3%BAt%2C_a_Royal_Sz%C3%A1ll%C3%B3val_(ma_Corinthia_Hotel)_szemben._Fortepan_15317.jpg)

At 06:00, on 4 November,[149] in the town of Szolnok, János Kádár proclaimed the "Hungarian Revolutionary Worker-Peasant Government". His statement declared "We must put an end to the excesses of the counter-revolutionary elements. The hour for action has sounded. We are going to defend the interest of the workers and peasants and the achievements of the people's democracy."[150] Later that evening, Kádár called upon "the faithful fighters of the true cause of socialism" to come out of hiding and take up arms. However, Hungarian support did not materialise; the fighting did not take on the character of an internally divisive civil war, but rather, in the words of a United Nations report, that of "a well-equipped foreign army crushing by overwhelming force a national movement and eliminating the Government."[151]

By 08:00 organised defence of the city evaporated after the radio station was seized, and many defenders fell back to fortified positions.[152] During the same hour, the parliamentary guard laid down their arms, and forces under Major General K. Grebennik captured Parliament and liberated captured ministers of the Rákosi-Hegedüs government. Among the liberated were István Dobi and Sándor Rónai, both of whom became members of the re-established socialist Hungarian government.[143] As they came under attack even in civilian quarters, Soviet troops were unable to differentiate military from civilian targets.[153] For this reason, Soviet tanks often crept along main roads firing indiscriminately into buildings.[152] Hungarian resistance was strongest in the industrial areas of Budapest, with Csepel heavily targeted by Soviet artillery and air strikes.[154]

The longest holdouts against the Soviet assault occurred in Csepel and in Dunaújváros, where fighting lasted until 11 November before the insurgents finally succumbed to the Soviets.[61] At the end of the fighting, Hungarian casualties totalled at around 2,500 dead with an additional 20,000 wounded. Budapest bore the brunt of the bloodshed, with 1,569 civilians killed.[61] Approximately 53 percent of the dead were workers, and about half of all the casualties were people younger than thirty. On the Soviet side, 699 men were killed, 1,450 men were wounded, and 51 men were missing in action. Estimates place around 80 percent of all casualties occurring in fighting with the insurgents in the eighth and ninth districts of Budapest.[61][155][156]

Soviet version of the events

Soviet reports of the events surrounding, during, and after the disturbance were remarkably consistent in their accounts, more so after the Second Soviet intervention cemented support for the Soviet position among international Communist Parties. Pravda published an account 36 hours after the outbreak of violence, which set the tone for all further reports and subsequent Soviet historiography:[157]

- On 23 October, the honest socialist Hungarians demonstrated against mistakes made by the Rákosi and Gerő governments.

- Fascist, Hitlerite, reactionary, counter-revolutionary hooligans financed by the imperialist West took advantage of the unrest to stage a counter-revolution.

- The honest Hungarian people under Nagy appealed to Soviet (Warsaw Pact) forces stationed in Hungary to assist in restoring order.

- The Nagy government was ineffective, allowing itself to be penetrated by counter-revolutionary influences, weakening then disintegrating, as proven by Nagy's culminating denouncement of the Warsaw Pact.

- Hungarian patriots under Kádár broke with the Nagy government and formed a government of honest Hungarian revolutionary workers and peasants; this genuinely popular government petitioned the Soviet command to help put down the counter-revolution.

- Hungarian patriots, with Soviet assistance, smashed the counter-revolution.

The first Soviet report came out 24 hours after the first Western report. Nagy's appeal to the United Nations was not reported. After Nagy was arrested outside the Yugoslav embassy, his arrest was not reported. Nor did accounts explain how Nagy went from patriot to traitor.[158] The Soviet press reported calm in Budapest while the Western press reported a revolutionary crisis was breaking out. According to the Soviet account, Hungarians never wanted a revolution at all.[157]

In January 1957, representatives of the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania met in Budapest to review internal developments in Hungary since the establishment of the Soviet-imposed government. A communiqué on the meeting "unanimously concluded" that Hungarian workers, with the leadership of the Kádár government and support of the Soviet army, defeated attempts "to eliminate the socialist achievements of the Hungarian people".[159]

Soviet, Chinese, and other Warsaw Pact governments urged Kádár to proceed with interrogation and trial of former Nagy government ministers, and asked for punitive measures against the"counter-revolutionists".[159][160] In addition the Kádár government published an extensive series of "white books" (The Counter-Revolutionary Forces in the October Events in Hungary) documenting real incidents of violence against Communist Party and ÁVH members, and the confessions of Nagy supporters. These white books were widely distributed in several languages in most of the socialist countries and, while based in fact, present factual evidence with a colouring and narrative not generally supported by non-Soviet aligned historians.[161]

Aftermath

Hungary

In the immediate aftermath, many thousands of Hungarians were arrested. Eventually, 26,000 of these were brought before the Hungarian courts, 22,000 were sentenced and imprisoned, 13,000 interned, and 229 executed. Hundreds were also deported to the Soviet Union, many without evidence. Approximately 200,000[162] fled Hungary as refugees.[163][164][165] Former Hungarian Foreign Minister Géza Jeszenszky estimated 350 were executed.[129] Sporadic resistance and strikes by workers' councils continued until mid-1957, causing economic disruption.[166] By 1963, most political prisoners from the 1956 Hungarian revolution had been released.[167]

With most of Budapest under Soviet control by 8 November, Kádár became Prime Minister of the "Revolutionary Worker-Peasant Government" and General Secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party. Few Hungarians rejoined the reorganised Party, its leadership having been purged under the supervision of the Soviet Praesidium, led by Georgy Malenkov and Mikhail Suslov.[168] Although Party membership declined from 800,000 before the uprising to 100,000 by December 1956, Kádár steadily increased his control over Hungary and neutralised dissenters. The new government attempted to enlist support by espousing popular principles of Hungarian self-determination voiced during the uprising, but Soviet troops remained.[169] After 1956 the Soviet Union severely purged the Hungarian Army and reinstituted political indoctrination in the units that remained. In May 1957, the Soviet Union increased its troop levels in Hungary and by treaty Hungary accepted the Soviet presence on a permanent basis.[170]

The Red Cross and the Austrian Army established refugee camps in Traiskirchen and Graz.[165][171] Imre Nagy along with Georg Lukács, Géza Losonczy, and László Rajk's widow, Júlia, took refuge in the Embassy of Yugoslavia as Soviet forces overran Budapest. Despite assurances of safe passage out of Hungary by the Soviets and the Kádár government, Nagy and his group were arrested when attempting to leave the embassy on 22 November and taken to Romania. Losonczy died while on a hunger strike in prison awaiting trial when his jailers "carelessly pushed a feeding tube down his windpipe."[172]

The remainder of the group was returned to Budapest in 1958. Nagy was executed, along with Pál Maléter and Miklós Gimes, after secret trials in June 1958. Their bodies were placed in unmarked graves in the Municipal Cemetery outside Budapest.[173]

During the November 1956 Soviet assault on Budapest, Cardinal Mindszenty was granted political asylum at the United States embassy, where he lived for the next 15 years, refusing to leave Hungary unless the government reversed his 1949 conviction for treason. Because of poor health and a request from the Vatican, he finally left the embassy for Austria in September 1971.[174]

International

Despite Cold War rhetoric by western countries espousing a roll-back of the domination of Europe by the USSR and Soviet promises of the imminent triumph of socialism, national leaders of this period as well as later historians saw the failure of the uprising in Hungary as evidence that the Cold War in Europe had become a stalemate.[175]

The Foreign Minister of West Germany recommended that the people of Eastern Europe be discouraged from "taking dramatic action which might have disastrous consequences for themselves." The Secretary-General of NATO called the Hungarian revolt "the collective suicide of a whole people".[176] In a newspaper interview in 1957, Khrushchev commented "support by United States ... is rather in the nature of the support that the rope gives to a hanged man."[177]

In January 1957, United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld, acting in response to UN General Assembly resolutions requesting investigation and observation of the events in Soviet-occupied Hungary, established the Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary.[178] The Committee, with representatives from Australia, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Denmark, Tunisia, and Uruguay, conducted hearings in New York, Geneva, Rome, Vienna, and London. Over five months, 111 refugees were interviewed including ministers, military commanders and other officials of the Nagy government, workers, revolutionary council members, factory managers and technicians, Communists and non-Communists, students, writers, teachers, medical personnel, and Hungarian soldiers. Documents, newspapers, radio transcripts, photos, film footage, and other records from Hungary were also reviewed, as well as written testimony of 200 other Hungarians.[179]

The governments of Hungary and Romania refused the UN officials of the Committee entry, and the government of the Soviet Union did not respond to requests for information.[180] The 268-page Committee Report[181] was presented to the General Assembly in June 1957, documenting the course of the uprising and Soviet intervention, and concluding that "the Kádár government and Soviet occupation were in violation of the human rights of the Hungarian people."[182] A General Assembly resolution was approved, deploring "the repression of the Hungarian people and the Soviet occupation" but no other action was taken.[183] The chairman of the Committee was Alsing Andersen, a Danish politician and leading figure of Denmark's Social Democratic Party. He served in the Buhl government in 1942 during the Nazi German occupation of Denmark. He defended collaboration with the occupation forces and denounced the Resistance. He was appointed Interior Minister in 1947, but resigned because of scrutiny of his role in 1940 as Defence Minister. He then entered Denmark's UN delegation in 1948.[184][185]

The Committee Report and the motives of its authors were criticised by delegations to the United Nations. The Hungarian representative disagreed with the report's conclusions, accusing it of falsifying the events, and argued that the establishment of the Committee was illegal. The Committee was accused of being hostile to Hungary and its social system.[186] An article in the Russian journal "International Affairs", published by the Foreign Affairs Ministry, carried an article in 1957 in which it denounced the report as a "collection of falsehoods and distortions".[187]

Time magazine named the Hungarian Freedom Fighter its Man of the Year for 1956. The accompanying Time article comments that this choice could not have been anticipated until the explosive events of the revolution, almost at the end of 1956. The magazine cover and accompanying text displayed an artist's depiction of a Hungarian freedom fighter, and used pseudonyms for the three participants whose stories are the subject of the article.[188]

In 2006, Hungarian Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány referred to this famous Time Man of the Year cover as "the faces of free Hungary" in a speech to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1956 uprising.[189] Prime Minister Gyurcsány, in a joint appearance with British Prime Minister Tony Blair, commented specifically on the Time cover itself, that "It is an idealised image but the faces of the figures are really the face of the revolutionaries"[190]

At the Melbourne Olympics in 1956, the Soviet handling of the Hungarian uprising led to a boycott by Spain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.[191] At the Olympic Village, the Hungarian delegation tore down the Communist Hungarian flag and raised the flag of Free Hungary in its place. A confrontation between Soviet and Hungarian teams occurred in the semi-final match of the water polo tournament on 6 December. The match was extremely violent, and was halted in the final minute to quell fighting among spectators. This match, now known as the "blood in the water match", became the subject of several films.[192][193] The Hungarian team won the game 4–0 and later was awarded the Olympic gold medal. In 1957, Norway was invited to the first ever Bandy World Championship but declined because the Soviet Union was invited too.

On Sunday, 28 October 1956, as some 55 million Americans watched Ed Sullivan's popular television variety show, with the then 21-year-old Elvis Presley headlining for the second time, Sullivan asked viewers to send aid to Hungarian refugees fleeing from the effects of the Soviet invasion. Presley himself made another request for donations during his third and last appearance on Sullivan's show on 6 January 1957. Presley then dedicated a song for the finale, which he thought fit the mood of the time, namely the gospel song "Peace in the Valley". By the end of 1957, these contributions, distributed by the Geneva-based International Red Cross as food rations, clothing, and other essentials, had amounted to some SFR 26 million (US$6 million in 1957 dollars), the equivalent of $51,200,000 in today's dollars.[194] On 1 March 2011, István Tarlós, the Mayor of Budapest, made Presley an honorary citizen, posthumously, and a plaza located at the intersection of two of the city's most important avenues was named after Presley, as a gesture of gratitude.

Meanwhile, as the 1950s drew to a close, the events in Hungary produced ideological fractures within the Communist parties of Western Europe. Within the Italian Communist Party (PCI) a split ensued: most ordinary members and the Party leadership, including Palmiro Togliatti and Giorgio Napolitano, regarded the Hungarian insurgents as counter-revolutionaries, as reported in l'Unità, the official PCI newspaper.[195] However Giuseppe Di Vittorio, chief of the Communist trade union CGIL, repudiated the leadership position, as did the prominent party members Antonio Giolitti, Loris Fortuna, and many other influential Communist intellectuals, who later were expelled or left the party. Pietro Nenni, the national secretary of the Italian Socialist Party, a close ally of the PCI, opposed the Soviet intervention as well. Napolitano, elected in 2006 as President of the Italian Republic, wrote in his 2005 political autobiography that he regretted his justification of Soviet action in Hungary, and that at the time he believed in Party unity and the international leadership of Soviet communism.[196]

Within the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), dissent that began with the repudiation of Stalin by John Saville and E. P. Thompson, influential historians and members of the Communist Party Historians Group, culminated in a loss of thousands of party members as events unfolded in Hungary. Peter Fryer, correspondent for the CPGB newspaper The Daily Worker, reported accurately on the violent suppression of the uprising, but his dispatches were heavily censored.[140] Fryer resigned from the paper upon his return, and was later expelled from the Communist Party

In France, moderate Communists, such as historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, resigned, questioning the French Communist Party's policy of supporting Soviet actions. The French philosopher and writer Albert Camus wrote an open letter, The Blood of the Hungarians, criticising the West's lack of action. Even Jean-Paul Sartre, still a determined Communist, criticised the Soviets in his article Le Fantôme de Staline, in Situations VII.[197] Left Communists were particularly supportive of the revolution.

Commemoration

In December 1991, the preamble of the treaties with the dismembered Soviet Union, under Mikhail Gorbachev, and Russia, represented by Boris Yeltsin, apologised officially for the 1956 Soviet actions in Hungary. This apology was repeated by Yeltsin in 1992 during a speech to the Hungarian parliament.[129]

On 13 February 2006, the US State Department commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice commented on the contributions made by 1956 Hungarian refugees to the United States and other host countries, as well as the role of Hungary in providing refuge to East Germans during the 1989 protests against Communist rule.[198] US President George W. Bush also visited Hungary on 22 June 2006, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary.[199]

On 16 June 1989, the 31st anniversary of his execution, Imre Nagy's body was reburied with full honours.[173] The Republic of Hungary was declared in 1989 on the 33rd anniversary of the Revolution, and 23 October is now a Hungarian national holiday.[200]

In the north-west corner of MacArthur Park in Los Angeles, California, the Hungarian-American community built a commemorative statue to honour the Hungarian freedom fighters. Built in the late 1960s, the obelisk statue stands with an American eagle watching over the city of Los Angeles.

See also

- Significant events of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

- Cultural representations of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

- House of Terror Museum in Budapest

- "Blood in the Water match" on the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne

- Kronstadt rebellion

- Prague Spring

- Western betrayal

- Children of Glory

- 1953 East German Uprising

- Poznań 1956 protests

References

- ↑ Sources vary widely on numbers of Soviet forces involved in the intervention. The UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) estimated 75,000–200,000 troops and 1,600–4,000 tanks OSZK.hu (p. 56, para. 183), but recently released Soviet archives (available in Lib.ru, Maksim Moshkow's Library) list the troop strength of the Soviet forces as 31,550, with 1,130 tanks and self-propelled artillery pieces. Lib.ru Archived 9 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. (in Russian)

- ↑ Györkei, Jenõ; Kirov, Alexandr; Horvath, Miklos (1999). Soviet Military Intervention in Hungary, 1956. New York: Central European University Press. p. 370 table 111. ISBN 963-9116-35-1.

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter V footnote 8" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ "B&J": Jacob Bercovitch and Richard Jackson, International Conflict : A Chronological Encyclopedia of Conflicts and Their Management 1945–1995 (1997)

- ↑ Alternate references are "Hungarian Revolt" and "Hungarian Uprising". In Hungarian, first the term "felkelés" (uprising) was used, then in the 1957–1988 period, the term "ellenforradalom" (counter-revolution) was mandated by the government, while the new official name after 1990 has become "forradalom és szabadságharc" (revolution and freedom fight) to imitate the old expression for the 1848–1849 revolution. Another explanation of the terms is that "Revolution" conforms to both English (see US Department of State background on Hungary) and Hungarian ("forradalom") conventions. There is a distinction between the "complete overthrow" of a revolution and an uprising or revolt that may or may not be successful (Oxford English Dictionary). The 1956 Hungarian event, although short-lived, is a true "revolution" in that the sitting government was deposed. Unlike the terms "coup d'état" and "putsch" that imply action of a few, the 1956 revolution was initiated by the masses.

- ↑ Kertesz, Stephen D. (1953). "Chapter VIII (Hungary, a Republic)". Diplomacy in a Whirlpool: Hungary between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana. pp. 139–52. ISBN 0-8371-7540-2. Retrieved 8 October 2006

- 1 2 3 UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II. A (Developments before 22 October 1956), paragraph 47 (p. 18)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter IX D, para 426 (p. 133)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II.N, para 89(xi) (p. 31)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II. A (Developments before 22 October 1956), paragraphs 49 (p. 18), 379–80 (p. 122) and 382–85 (p. 123)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- 1 2 Crampton, R. J. (2003). Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century–and After, p. 295. Routledge: London. ISBN 0-415-16422-2.

- ↑ Video: Hungary in Flames CEU.hu producer: CBS (1958) – Fonds 306, Audiovisual Materials Relating to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, OSA Archivum, Budapest, Hungary ID number: HU OSA 306–0–1:40

- 1 2 3 4 Litván, György (1996). The Hungarian Revolution of 1956: Reform, Revolt and Repression. London: Longman.

- 1 2 Tőkés, Rudolf L. (1998). Hungary's Negotiated Revolution: Economic Reform, Social Change and Political Succession, p. 317. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-57850-7

- 1 2 John Lukacs (1994). Budapest 1900: A Historical Portrait of a City and Its Culture. Grove Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-8021-3250-5.

- 1 2 Gati, Charles (September 2006). Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt. Stanford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0-8047-5606-6. Gati describes "the most gruesome forms of psychological and physical torture ... The reign of terror (by the Rákosi government) turned out to be harsher and more extensive than it was in any of the other Soviet satellites in Central and Eastern Europe." He further references a report prepared after the collapse of communism, the Fact Finding Commission Törvénytelen szocializmus (Lawless Socialism): "Between 1950 and early 1953, the courts dealt with 650,000 cases (of political crimes), of whom 387,000 or 4 percent of the population were found guilty. (Budapest, Zrínyi Kiadó/Új Magyarország, 1991, 154).

- ↑ Kardos, József (2003). "Monograph" (PDF). Iskolakultúra (in Hungarian). University of Pécs. 6–7 (June–July 2003): 73–80. Retrieved 9 October 2006.

- ↑ Burant, Stephen R., ed. (1990). Hungary: a country study (2nd ed.). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 320., Chapter 2 (The Society and Its Environment) "Religion and Religious Organizations"

- ↑ Douglas, J. D. and Philip Comfort (eds.) (1992). Who's Who in Christian History, p. 478. Tyndale House: Carol Stream, Illinois. ISBN 0-8423-1014-2

- ↑ The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: Armistice Agreement with Hungary; 20 January 1945 Archived 9 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ↑ Kertesz, Stephen D. (1953). "Memorandum of the Hungarian National Bank on Reparations, Appendix Document 16". Diplomacy in a Whirlpool: Hungary between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana. ISBN 0-8371-7540-2.

- ↑ Magyar Nemzeti Bank – English Site: History Retrieved 27 August 2006 According to Wikipedia Hyperinflation article, 4.19 × 1016 percent per month (prices doubled every 15 hours).

- ↑ Kertesz, Stephen D. (1953). "Chapter IX (Soviet Russia and Hungary's Economy)". Diplomacy in a Whirlpool: Hungary between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana. p. 158. ISBN 0-8371-7540-2.

- ↑ Bognár, Sándor; Iván Pető; Sándor Szakács (1985). A hazai gazdaság négy évtizedének története 1945–1985 (The history of four decades of the national economy, 1945–1985). Budapest: Közdazdasági és Jogi Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963-221-554-0. pp. 214, 217 (in Hungarian)

- ↑ Transformation of the Hungarian economy The Institute for the History of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution (2003). Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ↑ Library of Congress: Country Studies: Hungary, Chapter 3 Economic Policy and Performance, 1945–85. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ↑ János M. Rainer (4 October 1997). "Stalin and Rákosi, Stalin and Hungary, 1949–1953". "European Archival Evidence. Stalin and the Cold War in Europe" workshop, Budapest, 1956 Institute. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Gati, Charles (September 2006). Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt. Stanford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-8047-5606-6.

- ↑ Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, First Secretary, Communist Party of the Soviet Union (24–25 February 1956). "On the Personality Cult and its Consequences". Special report at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Archived from the original on 4 August 2006. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II. A (Developments before 22 October 1956), paragraph 48 (p. 18)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA by Tim Weiner, p. 144 (2008 Penguin Books edition)

- ↑ Halsall, Paul (Editor) (November 1998). "The Warsaw Pact, 1955; Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance". Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Fordham University. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ↑ Video (in German): Berichte aus Budapest: Der Ungarn Aufstand 1956 {{CEU.hu Director: Helmut Dotterweich, (1986) – Fonds 306, Audiovisual Materials Relating to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, OSA Archivum, Budapest, Hungary ID number: HU OSA 306-0-1:27}}

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter VIII The Question Of The Presence And The Utilization Of The Soviet Armed Forces In The Light Of Hungary's International Commitments, Section D. The demand for withdrawal of Soviet armed forces, para 339 (p. 105)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- 1 2 3 "Notes from the Minutes of the CPSU CC Presidium Meeting with Satellite Leaders, 24 October 1956" (PDF). The 1956 Hungarian Revolution, A History in Documents. George Washington University: The National Security Archive. 4 November 2002. Retrieved 2 September 2006.

- 1 2 Machcewicz, Paweł (June 2006). "1956 – A European Date". culture.pl. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Borhi, László (1999). "Containment, Rollback, Liberation or Inaction? The United States and Hungary in the 1950s" (PDF). Journal of Cold War Studies. 1 (3): 67–108. doi:10.1162/152039799316976814. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ↑ Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA by Tim Weiner, page 145 (2008 Penguin Books edition)

- 1 2 Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA by Tim Weiner, p. 149 (2008 Penguin Books edition)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter IX. B (The background of the uprising), para 384 (p. 123)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ Andreas, Gémes (2006). James S. Amelang, Siegfried Beer, eds. International Relations and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution: a Cold War Case Study (PDF). Public Power in Europe. Studies in Historical Transformations. CLIOHRES. p. 231. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- ↑ Internet Modern History Sourcebook: Resolution by students of the Building Industry Technological University: Sixteen Political, Economic, and Ideological Points, Budapest, 22 October 1956. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ United Nations Report of the Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary. p. 145, para 441. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- ↑ Video (in Hungarian): The First Hours of the Revolution {{ director: György Ordódy, producer: Duna Televízió – Fonds 306, Audiovisual Materials Relating to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, OSA Archivum, Budapest, Hungary ID number: HU OSA 306-0-1:40}}

- ↑ "SIR, – The whole body of Hungarian intel- lectuals has issued the following Manifesto:". The Spectator Archive. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heller, Andor (1957). No More Comrades. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company. pp. 9–84. ASIN B0007DOQP0.

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II. A (Meetings and demonstrations), para 54 (p. 19)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- 1 2 3 UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II. C (The First Shots), para 55 (p. 20) & para 464 (p. 149)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ "A Hollow Tolerance". Time. 23 July 1965. Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- 1 2 UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II. C (The First Shots), para 56 (p. 20)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II. C (The First Shots), paragraphs 56–57 (p. 20)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ Gati, Charles (September 2006). Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt. Stanford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 0-8047-5606-6. Gati states: "discovered in declassified documents, the Soviet Ministry of Defense had begun to prepare for large-scale turmoil in Hungary as early as July 1956. Codenamed "Wave", the plan called for restoration of order in less than six hours ... the Soviet Army was ready. More than 30,000 troops were dispatched to—and 6,000 reached—Budapest by the 24th, that is, in less than a day."

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II.C, para 58 (p. 20)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter IV.C, para 225 (p. 71)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- 1 2 UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II.C, para 57 (p. 20)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II.N, para 89(ix) (p. 31)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter IV. B (Resistance of the Hungarian people) para 166 (p. 52) and XI. H (Further developments) para 480 (p 152)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- 1 2 UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter X.I, para 482 (p. 153)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ Gati, Charles (September 2006). Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt. Stanford University Press. p. 159. ISBN 0-8047-5606-6.

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II.F, para 64 (p. 22)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lendvai, Paul (2008). One Day That Shook the Communist World: The 1956 Hungarian Uprising and Its Legacy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II.F, para 65 (p. 22)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter XII.B, para 565 (p. 174)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ Олег Филимонов: Мифы о восстании – ПОЛИТ.РУ. Polit.ru (30 October 2006). Retrieved on 28 October 2016.

- ↑ János Berecz. 1956 Counter-Revolution in Hungary. Akadémiai Kiadó. 1986. p. 116

- ↑ Berecz, 117

- ↑ Cold War International History Project (CWIHP), KGB Chief Serov's report, 29 October 1956, (by permission of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars) Retrieved 8 October 2006

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter IV.C, para 167 (p. 53)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)

- ↑ Gati, Charles (2006). Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest, and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt (Cold War International History Project Series). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-5606-6. (pp. 176–77)

- ↑ UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II. F (Political Developments) II. G (Mr. Nagy clarifies his position), paragraphs 67–70 (p. 23)" (PDF). (1.47 MB)