1935 Labor Day hurricane

| Category 5 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Weather Bureau surface weather map of the hurricane moving up the west coast of Florida | |

| Formed | August 29, 1935 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 10, 1935 |

| (Extratropical after September 6) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 185 mph (295 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure |

892 mbar (hPa); 26.34 inHg (Lowest recorded in continental United States) |

| Fatalities | 408 total |

| Areas affected | |

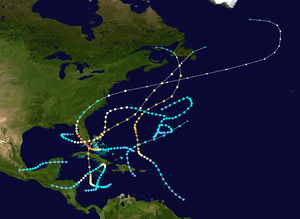

| Part of the 1935 Atlantic hurricane season | |

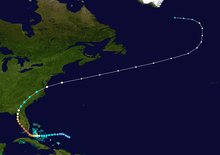

The 1935 Labor Day Hurricane was the most intense hurricane to make landfall in the United States on record, as well as the 3rd most intense Atlantic hurricane ever.[1] The second tropical cyclone, second hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 1935 Atlantic hurricane season, the Labor Day Hurricane was the first of three Category 5 hurricanes to strike the United States at that intensity during the 20th century (the other two being 1969's Hurricane Camille and 1992's Hurricane Andrew). After forming as a weak tropical storm east of the Bahamas on August 29, it slowly proceeded westward and became a hurricane on September 1.

On Long Key it struck about midway through the calm. The waters quickly receded after carving new channels connecting the bay with the ocean. But gale force winds and high seas persisted into Tuesday, preventing rescue efforts. The storm continued northwest along the Florida west coast, weakening before its second landfall near Cedar Key, Florida, on September 4.

The compact and intense hurricane caused extreme damage in the upper Florida Keys, as a storm surge of approximately 18 to 20 feet (5.5–6 meters) swept over the low-lying islands. The hurricane's strong winds and the surge destroyed nearly all the structures between Tavernier and Marathon. The town of Islamorada was obliterated. Portions of the Key West Extension of the Florida East Coast Railway were severely damaged or destroyed. The hurricane also caused additional damage in northwest Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas.

Meteorological history

“The first indications of conditions favorable to the origin of this disturbance were noted during the last 2 or 3 days of August, to the eastward and northward of Turks Islands; but it was not until August 31 that a definite depression appeared near Long Island in the southeastern Bahamas, and deepened rapidly as it moved westward. … Hurricane intensity was doubtless reached by the developing disturbance near the south end of Andros Island on September 1.”[2] “A broad recurve brought it to the Florida Keys late on September 2. By that time it was of small diameter but of tremendous force. … There was a calm of forty minutes on Lower Matecumbe Key and about fifty-five minutes at the Long Key fishing camp, 9:20 to 10:15 p.m. The rate of progress of the hurricane was about ten miles an hour and the calm center must have been nine to ten miles in diameter. After leaving the Keys, the storm skirted the Florida Gulf coast on a broad recurve, passed inland at Cedar Keys and finally left the continent near Cape Henry.”[3] Heavy rainfall spread in advance and magnified to the left of the track across the Mid-Atlantic states. Rainfall totals of 16.7 inches (420 mm) in Easton, Maryland, and 13.4 inches (340 mm) at Atlantic City, New Jersey, were the highest seen with the storm.[4]

The storm continued into “the North Atlantic Ocean, where, off southern Greenland, it was lost on September 10 by merging with a cyclone of extratropical origin.”[2]

The first recorded instance of an aircraft flown for the specific purpose of locating a hurricane occurred on the afternoon of September 2. The Weather Bureau’s 1:30 PM advisory[5] placed the center of the hurricane at north latitude 23° 20’, west longitude 80° 15’, moving slowly westward. This was about 27 miles north of Isabela de Sagua, Villa Clara, Cuba, and 145 miles east of Havana. Captain Leonard Povey of the Cuban Army Air Corps volunteered to investigate the threat to the capital. Flying a Curtis Hawk II, Captain Povey, an American expatriate who was the CEAC's chief training officer, observed the storm north of its reported position but, flying an open-cockpit biplane, opted not to fly into it.[6][7][8] He later proposed an aerial hurricane patrol.[9] Nothing further came of this idea until June 1943 when Colonel Joe Duckworth and Lieutenant Ralph O'Hair flew into a hurricane near Galveston, Texas.[10]

Records

The Labor Day Hurricane was the most intense storm ever known to have struck the United States, having the lowest sea level pressure ever recorded in the United States—a central pressure of 892 mb (26.35 inHg)—suggesting an intensity of between 162 kt and 164 kt (186.4 mph – 188.7 mph). The somewhat compensating effects of a slow (7 kt, 8.1 mph) translational velocity along with an extremely tiny radius of maximum wind (5 nmi, 9.3 miles) led to an analyzed intensity at landfall of 160 kt (184.1 mph, Category 5). This is the highest intensity for a U.S. landfalling hurricane in HURDAT2, as 1969’s Hurricane Camille has been recently reanalyzed to have the second highest landfalling intensity with 150 kt (172.6 mph).[11]

Records of the lowest pressure were secured from three aneroid barometers, the values ranging from 26.75 to 26.98 inches. However, none of these barometers had previously been compared to standard. One of the barometers, owned by Ivar Olson, was shipped to the Weather Bureau in Washington where it was tested in the Instrument Division. Careful laboratory tests showed it to be an exceptionally responsive and reliable instrument and that the correct reading at the position of the needle indicated by Mr. Olson at the center of the storm was 26.35 inches. This is the world's lowest record of pressure at a land station.[12]

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Landfall pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 mbar (hPa) |

| 2 | Gilbert | 1988 | 900 mbar (hPa) |

| Camille | 1969 | ||

| 4 | Dean | 2007 | 905 mbar (hPa) |

| Source: National Hurricane Center | |||

| Most intense Atlantic hurricanes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Pressure | ||

| hPa | inHg | ||||

| 1 | Wilma | 2005 | 882 | 26.05 | |

| 2 | Gilbert | 1988 | 888 | 26.23 | |

| 3 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 | 26.34 | |

| 4 | Rita | 2005 | 895 | 26.43 | |

| 5 | Allen | 1980 | 899 | 26.55 | |

| 6 | Camille | 1969 | 900 | 26.58 | |

| 7 | Katrina | 2005 | 902 | 26.64 | |

| 8 | Mitch | 1998 | 905 | 26.73 | |

| Dean | 2007 | ||||

| 10 | "Cuba" | 1924 | 910 | 26.88 | |

| Ivan | 2004 | ||||

| Source: HURDAT[13] | |||||

| Strongest U.S. landfalling hurricanes*† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Wind speed | ||

| Mph | Km/h | ||||

| 1 | “Labor Day” | 1935 | 185 | 295 | |

| 2 | Camille | 1969 | 175 | 280 | |

| 3 | Andrew | 1992 | 165 | 265 | |

| 4 | |||||

| “Last Island” | 1856 | 150 | 240 | ||

| “Indianola” | 1886 | 150 | 240 | ||

| “Florida Keys” | 1919 | 150 | 240 | ||

| “Freeport” | 1932 | 150 | 240 | ||

| Charley | 2004 | 150 | 240 | ||

| 9 | "Great Miami" | 1926 | 145 | 230 | |

| "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 145 | 230 | ||

| Source: HURDAT,[13] Hurricane Research Division[14] | |||||

| *List refers to hurricanes that struck the lower 48 states, excluding U.S. territories elsewhere. †Strength refers to maximum sustained wind speed | |||||

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Landfall pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 mbar (hPa) |

| 2 | Camille | 1969 | 900 mbar (hPa) |

| 3 | Katrina | 2005 | 920 mbar (hPa) |

| 4 | Andrew | 1992 | 922 mbar (hPa) |

| 5 | "Indianola" | 1886 | 925 mbar (hPa) |

| 6 | "Florida Keys" | 1919 | 927 mbar (hPa) |

| 7 | "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 929 mbar (hPa) |

| 8 | "Great Miami" | 1926 | 930 mbar (hPa) |

| Donna | 1960 | 930 mbar (hPa) | |

| 10 | Carla | 1961 | 931 mbar (hPa) |

| Source: HURDAT,[13] Hurricane Research Division[14] | |||

Preparations

Northeast storm warnings[15] were ordered displayed from Fort Pierce to Fort Myers in the September 1, 9:30 AM Weather Bureau advisory.[16] Upon receipt of this advisory the U.S. Coast Guard Station, Miami, FL, sent a plane along the coast to advise boaters and campers of the impending danger by dropping message blocks. A second flight was made Sunday afternoon. All planes were placed in the hangar and its door closed at 10:00 AM Monday morning.[17][18] The 3:30 AM advisory, September 2 (Labor Day), predicted the disturbance "will probably pass through the Florida Straits Monday" and cautioned "against high tides and gales Florida Keys and ships in path."[19] The 1:30 PM advisory ordered hurricane warnings[15] for the Key West district[16] which extended north to Key Largo.[20] At around 2:00 PM, Fred Ghent, Assistant Administrator, Florida Emergency Relief Administration, requested a special train to evacuate the veterans work camps located in the upper keys.[21] It departed Miami at 4:25 PM; delayed by a draw bridge opening, obstructions across the track, poor visibility and the necessity to back the locomotive below Homestead (so it could head out on the return trip[22]) the train finally arrived at the Islamorada station on Upper Matecumbe Key at about 8:20 PM. This coincided with an abrupt wind shift from northeast (Florida Bay) to southeast (Atlantic Ocean) and the arrival on the coast of the storm surge.[2]

Impact

Three ships ran afoul of the storm. ″The Danish motorship Leise Maersk was carried over Alligator Reef and grounded nearly 4 miles beyond, after being totally disabled by the wind and sea, with engine room flooded."[23] This was just offshore of Upper Matecumbe Key. No one died and the ship was salvaged on Sept. 20. ″The American tanker Pueblo drifted helplessly in the storm from 2 to 10 p. m. of September 2; she went out of control near 24°40′N 80°25′W / 24.667°N 80.417°W, and was carried completely around the storm center, finding herself in 8 hours about 25 miles northeastward of her original position, and just barely able to claw off Molasses Reef.″[23] However, the ship that made the headlines was the American steamship Dixie out of New Orleans, with a crew of 121 and 229 passengers.[24] It ran aground on French Reef, near Key Largo, without loss of life; it was re-floated on September 19 and towed to New York.[2]

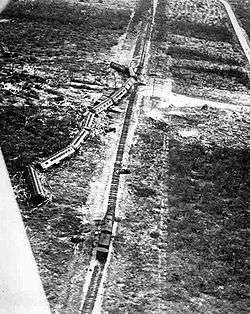

On Upper Matecumbe Key, near Islamorada, the eleven-car evacuation train encountered a powerful storm surge topped by cresting waves. Eleven cars[25] were swept from the tracks, leaving only the locomotive and tender upright. Remarkably, everyone on the train survived.[26] Only the locomotive and tender remained on the rails, and both were barged back to Miami several months later.

The hurricane left a path of near destruction in the Upper Keys, centered on what is today the village of Islamorada. The eye of the storm passed a few miles to the southwest creating a calm of about 40 minutes duration over Lower Matecumbe and 55 minutes (9:20 - 10:15 PM) over Long Key. At Camp #3 on Lower Matecumbe the surge arrived near the end of the calm with the wind close behind.[27] Nearly every structure was demolished, and some bridges and railway embankments were washed away. The links — rail, road, and ferry boats — that chained the islands together were broken. The main transportation route linking the Keys to mainland Florida was one railroad line, the Florida Overseas Railroad portion of the Florida East Coast Railway. The Islamorada area was devastated, although the hurricane's destructive path was narrower than most tropical cyclones. Its eye was eight miles (13 km.) across and the fiercest winds extended 15 miles (24 km.) off the center, less than 1992's Hurricane Andrew, which was also a relatively small and catastrophic Category 5 hurricane. Craig Key, Long Key, and Upper Matecumbe and Lower Matecumbe Keys suffered the worst. The storm caused wind and flood damage along the Florida panhandle and into Georgia, with significant damage to the Tampa Bay Area.[28] After the third day of the storm corpses swelled and split open in the subtropical heat, according to rescue workers. Public health officials ordered plain wood coffins holding the dead to be stacked and burned in several locations. The National Weather Service estimated 408 deaths from the hurricane. Bodies were recovered as far away as Flamingo and Cape Sable on the southwest tip of the Florida mainland.

The United States Coast Guard and other state and federal agencies organized evacuation and relief efforts. Boats and airplanes carried injured survivors to Miami. The railroad was never rebuilt, but temporary bridges and ferry landings were under construction as soon as materials arrived. On March 29, 1938, the last gap in the Overseas Highway linking Key West to the mainland was completed. The new highway incorporated the roadbed and surviving bridges of the railway.

Response

Veterans' work camps

Three veterans’ work camps existed in the Florida Keys before the hurricane: #1 on Windley Key, #3 and #5 on Lower Matecumbe Key.[29] The camp payrolls for August 30 listed 695 veterans.[30] They were employed in a project to complete the Overseas Highway connecting the mainland with Key West. The camps, including 7 in Florida and 4 in South Carolina, were established by Harry L. Hopkins, director of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). In the autumn of 1934 the problem of transient veterans in Washington DC “threatened … to become acute and did become acute in January.”[31] Facilities in the capital were inadequate to handle the large numbers of veterans seeking jobs.[32][33] President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with Mr. Hopkins and Robert Fechner, director of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to discuss solutions. He “suggested the Southern camp plan and approved the program worked out by Mr. Hopkins for their establishment and maintenance.”[34] The VA identified eligible veterans.[35] FERA offered grants to the states for their construction projects if they would accept the veterans as laborers. The state Emergency Relief Administrations were responsible for the daily management of the camps.[36] In practice the state ERAs were very much the creatures of FERA, to the extent of handpicking the administrators.[37][38] That only two states participated was perhaps attributable to the then popular impression that the transient veterans were “diseased” bums and hoboes.[39] It was a characterization enthusiastically fed by the media. In August 1935 both Time Magazine[40] and the New York Times published sensational articles.[41][42] On Aug. 15, 1935, Hopkins announced the termination of the veterans work program and closure of all the camps.[43]

On August 26 and 27, 1935, one of the veterans, Albert C. Keith, wrote letters to both the President and Eleanor Roosevelt urging that the camps not be closed. Keith was editor of the weekly camp paper, the Key Veteran News. He was emphatic that the veterans were being defamed and that their work program was actually a success story, rehabilitating many veterans for return to civilian life. The News published occasional reports from Camp #2, Mullet Key, St. Petersburg, Florida, at the entrance to Tampa Bay. This was the "colored" veterans camp; the Keys camps were white only. In early August the colored veterans were transferred to the new Camp #8 in Gainesville, Florida.[44]

Rescue

Improved weather conditions on Wednesday, September 4, permitted the evacuation of survivors to begin. Participating in the rescue were

- American Red Cross,

- Florida National Guard,

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA),

- Works Progress Administration (WPA),

- Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC),

- United States Coast Guard,

- American Legion,[45]

- Veterans of Foreign Wars,

- Dade County Undertakers Association,

- Dade County Medical Society,

- city and county officials,

- and numerous individuals (including Ernest Hemingway). Headquarters of the operation was the near shore of Snake Creek on Plantation Key. With the bridge over the creek washed out this was the farthest point south on the highway. On September 5 at a meeting of all public and private agencies involved Governor David Sholtz placed the sheriffs of Monroe and Dade Counties in overall control.[46]

On the evening of September 4, 1935, Brigadier General Frank T. Hines, VA Administrator, received a phone call from Hyde Park, New York. It was Stephen Early, the President’s press secretary. He had orders from the President who was very distressed by the news from Florida. The VA was to: 1. Cooperate with FERA in seeing that everything possible be done for those injured in the hurricane; 2. See that the bodies were properly cared for shipment home to relatives, and that those bodies for which shipment home was not requested be sent to Arlington National Cemetery; and, 3. Conduct a very careful joint investigation with Mr. Hopkins’ organization, to determine whether there was any fault that would lie against anyone in the Administration. Hines’ representative in Florida was to take full charge of the situation and all other organizations and agencies were ordered to cooperate.[47]

The President’s first order was straight forward and promptly executed. 124 injured veterans were treated in Miami area hospitals; 9 of these died. 56 were later transferred to VA medical facilities.[48] Uninjured veterans were removed to Camp Foster in Jacksonville and evaluated for transfer to the CCC; those declining transfer or deemed unemployable were paid off and given tickets home.[49] All of the FERA transient camps were closed in November 1935.[50] In December 1935 FERA itself was absorbed within the new WPA, also directed by Hopkins.[51]

Recovery

The second and third orders, however, were almost immediately compromised. At a news conference on September 5, Hopkins asserted that there was no negligence traceable to FERA in the failed evacuation of the camps as the Weather Bureau advisories had given insufficient warning. He also dispatched his assistant, Aubrey Willis Williams, to Florida to coordinate FERA efforts and to investigate the deaths.[52] Williams and Hines’ assistant, Colonel George E. Ijams, both arrived in Miami on September 6. Ijams concentrated on the dead, their collection, identification and proper disposition.[53] This was to prove exceptionally difficult. Bodies were scattered throughout the Keys and their rapid decomposition created ghastly conditions. State and local health officials demanded a ban on all movement of bodies and their immediate burial or cremation in place; the next day Governor Sholtz so ordered.[54] This was reluctantly agreed to by Hines with the understanding that those buried would be later disinterred and shipped home or to Arlington when permitted by the State health authorities.[55]

The cremations began on Saturday, September 7; 38 bodies were burned together at the collection point beside Snake Creek. Over the next week 136 bodies were cremated on Upper Matecumbe Key at 12 different locations. On Lower Matecumbe Key 82 were burned at 20 sites. On numerous small keys in Florida Bay bodies were either burned or buried where found. This effort continued into November. 123 bodies had been transported to Miami before the embargo. These were processed at a temporary morgue staffed by fingerprint experts and 8 volunteer undertakers under tents at Woodlawn Park Cemetery (3260 SW 8th St, Miami). The intention was to identify the remains and prepare them for burial or further shipment. With the embargo in force immediate burial of all the bodies at Woodlawn was mandatory. FERA purchased a plot in Section 2A. The VA coordinated the ceremony with full military honors on September 8.[56] 109 bodies were buried in the FERA plot: 81 veterans, 9 civilians and 19 unidentified bodies.[57]

Some records claim 259 veterans were victims of the Hurricane:

- 47 civilians and 34 veterans cremated

- 61 civilians and 128 veterans {unknown} cremated

Total: 108 civilians and 162 veterans {cremated}

Of the rest:

- 42 civilians and 81 veterans known/buried

- 6 civilians and 9 veterans sent to relatives

- 7 civilians and 7 veterans unknown/buried

Total: 55 civilians and 97 veterans buried Total: 163 civilians and 259 veterans =422[58]

Although the Congressional Record [59] gives a report of 485 victims of the hurricane {257 veterans and 259 civilians}[60] the Record also breaks down 694 World War I veterans by name and their status as:

Survived:

- 443 number {437 living + 6 living, identification tentative}

Died:

- 251 broken down as:

- 2 listed as dead—dispositions of remains not listed

- 6 reburied in Hometowns

- 26 cremated

- 44 tentatively identified as dead

- 84 reburied in Woodlawn Cemetery, Miami

- 89 missing—believed dead [61]

The Florida Emergency Relief Administration reported that as of November 19, 1935, the total of dead stood at 423: 259 veterans and 164 civilians. These numbers are reflected on the Veterans Storm Relief Map (which see). By March 1, 1936, 62 additional bodies had been recovered bringing the total to 485: 257 veterans and 228 civilians.[62] The discrepancy in veterans’ deaths resulted from the difficulty in identifying bodies, particularly those found months after the hurricane, and a question of definition; whether to count just those on the camp payrolls or to include others, not enrolled, who happened to be veterans.

The Veterans’ Affairs Administration (VA) compiled its own list of veterans’ deaths:

121 Dead-positive identification,

90 Missing, and 45 Dead-identification tentative, totaling 256.

Five others are named in a footnote. One proved to be a misidentification of a previously listed veteran; two were state employees working at the camps; and two were unaffiliated veterans caught in the storm. This gives a total for all veterans of 260.[63] Adding this to the Florida Emergency Relief Administration number for civilians gives a total of 488 for all deaths. 12 of the dead were listed as "colored".[64]

Ernest Hemingway visited the veteran's camp by boat after weathering the hurricane at his home in Key West; he wrote about the devastation in a critical article titled "Who Killed the Vets?" for The New Masses magazine.[65] Hemingway implied that the FERA workers and families, who were unfamiliar with the risks of Florida hurricane season, were unwitting victims of a system that appeared to lack concern for their welfare. From Ernest Hemingway's statement on the tragedy:[66]

...wealthy people, yachtsmen, fishermen such as President Hoover and President Roosevelt, do not come to the Florida Keys in hurricane months.... There is a known danger to property. But veterans, especially the bonus-marching variety of veterans, are not property. They are only human beings; unsuccessful human beings, and all they have to lose is their lives. They are doing coolie labor for a top wage of $45 a month and they have been put down on the Florida Keys where they can't make trouble. It is hurricane months, sure, but if anything comes up, you can always evacuate them, can't you?...It is not necessary to go into the deaths of the civilians and their families since they were on the Keys of their own free will; they made their living there, had property and knew the hazards involved. But the veterans had been sent there; they had no opportunity to leave, nor any protection against hurricanes; and they never had a chance for their lives. Who sent nearly a thousand war veterans, many of them husky, hard-working and simply out of luck, but many of them close to the border of pathological cases, to live in frame shacks on the Florida Keys in hurricane months?

In the same issue of The New Masses appeared an editorial charging criminal negligence and a cartoon by Russell T. Limbach, captioned, An Act of God, depicting burning corpses.[67] A Washington Post editorial on Sept. 5, titled Ruin in the Veterans' Camps, stated the widely held opinion that the ″camps were havens of rest designed to keep Bonus Marchers away from Washington... Most of these veterans are drifters, psychopathic cases or habitual troublemakers... Those who are nor physically or mentally handicapped have no claim whatsoever to special rewards in return for bonus agitation."[68]

Investigation

Williams meanwhile rushed to complete the investigation. He finished on Sunday, September 8, the day an elaborate memorial service and mass burial of hurricane victims (both coordinated by Ijams) were held in Miami.[69] Ijams who had been too busy to participate in the investigation and had not questioned any of the 12 witnesses interrogated by Williams, nonetheless signed the 15 page report to the President.[70] That night Williams released it to the Miami press in a radio broadcast immediately following the memorial ceremony. Ijams considered the timing unfortunate after receiving several critical telephone messages.[71] The report exonerated everyone involved and concluded: “To our mind the catastrophe must be characterized as an act of God and was by its very nature beyond the power of man or instruments at his disposal to foresee sufficiently far enough in advance to permit the taking of adequate precautions capable of preventing the death and desolation which occurred.”[72] Early also found the publicity around the report "unfortunate". In a telegram to his colleague, assistant Presidential secretary Marvin H. McIntyre, Early wrote that he had authorized Hines to proceed with a "complete and exhaustive" joint investigation with Hopkins. Significantly Hines was to "instruct his investigator that under no circumstances will any statement be made to the Press until final report has been submitted to the President."[73] Hopkins gave similar instructions to his investigator. McIntyre also was involved in damage control. On Sept. 10, 1935, the Greater Miami Ministerial Association wrote the President an angry letter labeling the report a "whitewash". McIntyre forwarded it to FERA for a response. Williams returned a draft for the President's signature on Sept. 25th insisting the report was only preliminary and that the "final and detailed report ... will be both thorough and searching".[74]

Williams assigned John Abt, assistant general counsel for FERA, to complete the investigation. On Sept. 11, 1935, Hines directed the skeptical and meticulous David W. Kennamer to investigate the disaster. There was immediate friction between them; Kennamer believed Abt did not have an open mind and Abt felt further investigation was unnecessary.[75] Working with Harry W. Farmer, another VA investigator, Kennamer completed his 2 volume report on October 30, 1935. Farmer added a third volume concerning the identification of the veterans. Kennamer's report included 2,168 pages of exhibits,[76] 118 pages of findings,[77] and a 19 page general comment.[78] His findings differed substantially from those of Williams, citing three officials of the Florida Emergency Relief Administration as negligent (Administrator Conrad Van Hyning, Asst. Administrator Fred Ghent and Camp Superintendent Ray Sheldon). In a response to Abt's draft report to the President,[79] Ijams sided with Kennamer.[80] Hines and Hopkins never agreed on a final report, and Kennamer’s findings were suppressed. They remained so for decades.[81]

One might speculate that Hines wished to avoid a public quarrel with Hopkins, who had enjoyed Roosevelt’s patronage since his term as New York Governor. Hines was a holdover from the Hoover administration. Such an internal dispute would embarrass the Roosevelt administration at the time a vote on the Adjusted Compensation Payment Act (“Bonus Bill”) was upcoming (it passed on Jan. 27, 1936, over the President’s veto).[82] Also, 1936 was a presidential election year. Kennamer did appear at the House hearings in April 1936, along with Hines, Ijams, Williams and the 3 officials he pilloried in his report. He was not questioned about his controversial findings nor did he volunteer his opinions.[83]

On November 1, 1935, the American Legion completed its own report on the hurricane. The Legion's National Commander, Ray Murphy, mailed a copy to President Roosevelt. It concluded that:

...the blame for the loss of life can be placed on "Inefficiency, Indifference, and Ignorance." Inefficiency in the setup of the camps. Indifference of someone in charge as to the safety of the men. Ignorance of the real danger from a tropical hurricane. And these "I's" can be added together and they spell "Murder at Matacombe" [sic].[The] committee early in its investigation noticed a tendency on the part of some to reflect on the character of the men who were veterans in the camps. Several parties referred to them as "bums," "drunkards," "crazy men," "riff-raff" and the like. They seem to think that "they got what was coming to them."

How anyone could arrive at such a conclusion is impossible for us to determine.

If these men were "bums," "drunkards," "crazy men" etc. then it was all the more necessary that every precaution be taken to protect them. If they fell into this category they were subnormal men and should have been treated as such. If they were incapable of caring for themselves then the government should have placed them in hospitals and not have sent them to a wilderness in the high-seas on a so called "rehabilitation program."

Others testified that the men were well-behaved and that a great majority of them would have preferred to have been placed under military discipline in the camps. But these observations are of no real value except to show that some people are trying to "cover up" the real guilt of responsible parties.[84]

Williams prepared a response for the President stating: "A final report, based upon the facts obtained in this investigation [by the VA and FERA], will be submitted to me shortly. At that time I shall transmit a copy of the report to you for your information and consideration."[85]

Memorials

Islamorada

Standing just east of U.S. 1 at mile marker 82 in Islamorada, near where Islamorada's post office stood, is a simple monument[86] designed by the Florida Division of the Federal Art Project and constructed using Keys limestone ("keystone") by the Works Progress Administration. It was unveiled on November 14, 1937, with several hundred people attending.[87] Hines had been invited to speak but he declined.[88] His attitude to the project was unenthusiastic. In a letter to Williams on June 24, 1937, regarding what to do with the many skeletons of veterans recently discovered in the Keys, he wrote: ″It occurs to me that if a large memorial is erected adjacent to this highway at the place of the disaster it will be observed by all persons using the highway and will serve as a constant reminder of the unfortunate catastrophe which occurred.″[89] Hines recommended the remains be buried at Woodlawn. A frieze depicts palm trees amid curling waves, fronds bent in the wind. In front of the sculpture a ceramic-tile mural of the Keys covers a stone crypt, which holds victims' ashes from the makeshift funeral pyres, commingled with the skeletons.[87]

Although this is a grave site not a single name appears anywhere on the monument. This is not a requirement for the estimated 228 civilian dead, 55 of whom were buried where found or in various cemeteries.[90] A memorial with identifying information is a statutory entitlement for the veterans.[91] 170 were cremated or never identified. The VA has chosen not to memorialize them, despite current Federal law and President Roosevelt's order that Hines provide a burial with full military honors for every veteran not claimed by his family.

On February 18, 1939, President Roosevelt had the opportunity to see the memorial for himself. His motorcade passed through Islamorada on the way to Key West where he was to begin a visit with the battle fleet on maneuvers. But there is no record that he made a stop; no mention in newspaper reports,[92] the President’s daily calendar,[93] or in a press conference[94] held during a lunch stop at the CCC camp on West Summerland Key (renamed Scout Key in 2010). This omission is puzzling in that he had sent a telegram to the dedication in which he expressed “heartfelt sympathy” and said “the disaster which made desolate the hearts of so many of our people brought a personal sorrow to me because some years ago I knew many residents of the keys.”[87] The welcoming committee included Key West Mayor Willard M. Albury, and other local officials.[95]

The memorial was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places on March 16, 1995.[96] A Heritage Monument Trail plaque mounted on a coral boulder before the memorial reads:

The Florida Keys Memorial, known locally as the "Hurricane Monument," was built to honor hundreds of American veterans and local citizens who perished in the "Great Hurricane" on Labor Day, September 2, 1935. Islamorada sustained winds of 200 miles per hour and a barometer reading of 26.35 inches for many hours on that fateful holiday; most local buildings and the Florida East Coast Railway were destroyed by what remains the most savage hurricane on record. Hundreds of World War I veterans who had been camped in the Matecumbe area while working on the construction of U.S. Highway One for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were killed. In 1937 the cremated remains of approximately 300 people were placed within the tiled crypt in front of the monument. The monument is composed of native keystone, and its striking frieze depicts coconut palm trees bending before the force of hurricane winds while the waters from an angry sea lap at the bottom of their trunks. Monument construction was funded by the WPA and regional veterans' associations. Over the years the Hurricane Monument has been cared for by local veterans, hurricane survivors, and descendants of the victims.[97]

Local residents hold ceremonies at the monument every year on Labor Day (on the Monday holiday) and on Memorial Day to honor the veterans and the civilians who died in the hurricane.[98]

Woodlawn Park Cemetery

On January 31, 1936, Harvey W. Seeds Post No. 29, American Legion, Miami, Florida, petitioned FERA for the deed to the Woodlawn plot.[99] The Legion would use the empty grave sites for the burial of indigent veterans and accept responsibility for care of the plot. After some initial confusion as to the actual owner,[100] the State of Florida approved the title transfer. A monument was placed on the plot, inscribed: Erected by Harvey W. Seeds Post No. 29, The American Legion, in Memory of Our Comrades Who Lost Their Lives on the Florida Keys during the 1935 Hurricane, Lest We Forget.[101]

As with the Islamorada memorial no names appear. Nor were the individual grave sites marked. Again the VA chose not to obey the President’s order, this time to rebury the unclaimed bodies at Arlington. Two bodies were, however, exhumed by the families: Brady C. Lewis on Nov. 12, 1936;[102] and, Thomas K. Moore[103] on Jan. 20, 1937 (reburied at Arlington). Five more received grave markers at Woodlawn, leaving 74 unmarked graves of identified veterans. Efforts are ongoing to mark all these graves.[104]

One other veteran killed in the storm rests at Arlington, Daniel C. Main.[105] His was a special case, the only veteran who died in the camps who was neither cremated in the Keys nor buried at Woodlawn. Main was the camp medical director and was killed in the collapse of the small hospital at Camp #1. His body was quickly recovered by survivors and shipped to his family before the embargo.[106][107]

Veterans Key

On February 27, 2006, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names approved a proposal by Jerry Wilkinson, President, Historical Preservation Society of the Upper Keys, to name a small island off the southern tip of Lower Matecumbe Key for the veterans who died in the hurricane. It is near where Camp #3 was located. Veterans Key[108] and several concrete pilings are all that remain of the 1935 bridge construction project.[109]

Department of Veterans Affairs Actions

Government furnished grave markers are provided for eligible veterans buried in National Cemeteries, State veterans cemeteries and private cemeteries. Under VA regulations the applicant for a marker may only be the veteran’s next of kin; so, too, for memorials when the body is not available for burial.[110] Prior to a 2009 revision, not enforced until 2012, any person with knowledge of the veteran could apply. The revision prompted objections from groups and volunteers working to mark the many unmarked veterans’ graves, mostly from the Civil War era. They argued that the next-of-kin (if any) was often impossible to locate and that the very existence of an unmarked grave was evidence of the family’s indifference.[111] Two bills were introduced in Congress, H. R. 2018 and S. 2700 which would have again allowed unrelated applicants. Both bills died in committee. On October 1, 2014, the VA proposed a rule change which would include in the categories of applicants unrelated individuals.[112] However, this pertained only to applications on behalf of veterans who served prior to April 6, 1917 (American entry into WWI). For all WWI and later veterans only a family member, a personal representative or a legally recognized official responsible for the interment could apply. For memorial headstones and markers only a member of the decedent’s family could apply regardless of the dates of service. As there can be little expectation that the very persons who failed to apply since 1935 will now do so, this classification effectively denies memorialization benefits to the 241 veterans interred at Islamorada and Woodlawn, those who still lack any recognition.

See also

Films & Video

- Gold Diggers of 1933, Warner Brothers, 1933, concludes with Joan Blondell and Etta Moten remembering their forgotten men. This classic Busby Berkeley number is notable for its sympathetic portrayal of destitute war veterans, the very men sent to work in the camps. It is available on YouTube.

- In a Warner Brothers film, Key Largo, 1948, Lionel Barrymore describes the horrors of the 1935 hurricane to an anxious Edward G. Robinson, as another hurricane bears down on the Florida Keys. Special effects were used on the Warner lot in the film to re-create a powerful hurricane.

- Hurricane '35: The Deadly Deluge, Miles Associates Productions, 1997, documentary includes interviews with survivors of the 1935 Hurricane. Download available at 1935 Hurricane Documentary 27 min. video

- Nature's Fury: Storm of the Century, Tower Productions, was a 2006 made-for-TV (History Channel) docudrama of the 1935 Hurricane.

- Neal Dorst talks to WPEC Channel 12 News in West Palm Beach about the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, Aug. 7, 2014.

- Soldiers' graves still unmarked in Miami after 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, Published on May 26, 2015. Eighty years later, soldiers killed in the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, most intense hurricane ever to hit the United States, remain in unmarked graves in a Miami cemetery. Veteran Jerry Wilkinson is calling on Washington to stop ignoring the 74 wooden caskets. (Video by Walter Michot / Miami Herald) You Tube.

- Remembering 1935 Labor Day hurricane, most intense to ever hit U.S., Published on May 29, 2015. Everett Albury and Alma Pinder Dalton were children, just 6 and 11, in the Florida Keys when they survived one of the most powerful hurricanes to ever strike the United States. (Video by Jenny Staletovich / Miami Herald staff) You Tube.

Books

Histories

- Best, Gary (1992). FDR and the Bonus Marchers, 1933-1935. Praeger. ISBN 0275937151.

- Dickson and Allen (2006). The Bonus Army: An American Epic. Walker & Company. ISBN 0802777384.

- Douglas, Marjory (1958). Hurricane. Rinehart. ISBN 0891760156. Excerpt: The Florida Keys, 1935

- Drye, Willie (2002). Storm of the Century: The Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922801-0-5.

- Gallagher, Dan (2003). Florida's Great Ocean Railway: Building the Key West Extension. Pineapple Press. ISBN 1561647098.

- Knowles, Thomas Neil (2009). Category 5: The 1935 Labor Day Hurricane. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130331-0-1.

- Scott, Phil (2006). Hemingway's Hurricane. McGraw Hill Professional Publishing. ISBN 0-0714791-0-4.

- Tannehill, Ivan (2013). Hurricanes: Their Nature and History, Particularly Those Of The West Indies And The Southern Coasts Of The United States. Literary Licensing, LLC (first edition: Princeton University Press, 1938). ISBN 1258796015.

Government Publications

- United States. Congress. House. Committee on World War Veterans' Legislation. Florida Hurricane Disaster: Hearings Before the Committee On World War Veterans' Legislation, House of Representatives, Seventy-fourth Congress, Second Session, On H.R. 9486, a Bill for the Relief of Widows, Children And Dependent Parents of World War Veterans Who Died As the Result of the Florida Hurricane At Windley Island And Matecumbe Keys September 2, 1935 ... Washington DC: U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1936. Full text viewability at HathiTrust Digital Library

- United States. Department of Agriculture. Miscellaneous Publication No. 197: The Hurricane by Ivan R. Tannehill, Principal Meteorologist, Weather Bureau. Washington DC: U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1939. Ebook available at Google Books

Dissertations

- Seiler, Christine Kay (2003). The Veteran Killer: the Florida Emergency Relief Administration and the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. Thesis (Ph. D.)--Florida State University. Manuscript, Archival Material: English Worldcat

Novels and Short Stories

- Harlow, Joan (2007). Blown Away!. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 1416907815.

- Lafaye, Vanessa (2015). Under a Dark Summer Sky. Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 1492612510.

- Robuck, Erika (2012). Hemingway's Girl. Penguin. ISBN 1101599367.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas wrote the short story "September-Remember" soon after the hurricane. It appeared in the Saturday Evening Post; 12/7/1935, Vol. 208, Issue 23, p 12. It was anthologized in 1990:

- Douglas, Marjory (1990). Nine Florida Stories by Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Ed. Kevin M. McCarthy. University of North Florida Press. ISBN 0813009944.

- The storm also features in novelist Craig McDonald's novel Toros & Torsos (2008, Bleak House Books), incorporating Ernest Hemingway.

Audio Recording

- Audio recording of a song titled "Storm of the Century"

- lyrics of song titled "Storm of the Century"

References

- ↑ Hensen, Bob. "Remembering the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 in the Florida Keys". Weather Underground. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Monthly Weather Review, September 1935, p. 269. American Meteorological Society

- ↑ Tannehill, Hurricanes, Their Nature and History, 1938, pgs. 214-215

- ↑ United States Corp of Engineers (1945). Storm Total Rainfall In The United States. War Department. p. SA 1–26.

- ↑ Hearings, p. 184, Hathi Digital Trust

- ↑ "80th Anniversary of the Labor Day Hurricane and first hurricane reconnaissance", NOAA Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ Matthew Sitkowski (April 9, 2012). "Investigation and Prediction of Hurricane Eyewall Replacement Cycles" (PDF). University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 49. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ↑ Drye, Storm of the Century, pages 129-130

- ↑ Cuba May Use Planes to Scout for Hurricanes, AP, Schenectady Gazette, Sept. 23, 1935, p. 7

- ↑ NOAA History, Stories and Tales of the Weather Service, The 1943 "Surprise" Hurricane, The First Flight Into A Hurricane's Eye

- ↑ American Meteorological Society, Journal of Climate, August 15, 2014, A Reanalysis of the 1931–43 Atlantic Hurricane Database, Landsea et al., pg. 6114

- ↑ Tannehill, Hurricanes, Their Nature and History, 1938, p. 84. That is, the record at sea-level. For comparative purposes, barometric pressures are reduced to sea-level. Pressure decreases with altitude, hence the pressures actually indicated by barometers are ordinarily lowest at the station with the highest elevation. For example, a reading of 26.35 inches is common at a height of 3500 feet above sea-level, but on reduction to sea-level a correction of approximately one inch for each thousand feet is added, the exact amount depending upon temperature and other conditions (page footnote)

- 1 2 3 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (April 11, 2017). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- 1 2 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (February 2015). "Continental United States Hurricanes (Detailed Description)". aoml.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- 1 2 The Hurricane Warning Service, p. 3, June 1, 1933 Flickr

- 1 2 Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 184. HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ Memorandum of interview with Lt. Olson and Lt. Clemmer Kennamer

- ↑ U. S. Coast Guard 1935 Hurricane Report Wilkinson

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, testimony of Ivan R. Tannehill, p. 184. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 199. HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 336, record of phone calls by Fred Ghent. HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ There were no turntables on the Florida East Coast Railway below Miami. In routine operations locomotives were reversed using the "wye (rail)" junctions at Homestead, Marathon or Key West. In this case it was decided to use the Homestead way and run the locomotive backward to Camp #3 on Lower Matecumbe, and then, using a siding, move it to the other end of the train facing forward for the return trip. Using the Marathon wye would have allowed running the engine forward on both legs, but would have added 45.6 miles to the route, much of which was over open water. As it happened the hurricane's eye passed directly over the Long Key crossings. Caught there the entire train would have been lost in the bay. Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, Statements by Loftin, p. 504, Beals, p. 509 and Branch, p. 514.

- 1 2 Monthly Weather Review, Sept. 1935

- ↑ Miami Daily News, Sept.3,1935 Google News

- ↑ 6 coaches, 2 baggage cars, and 3 box cars. The box cars were at the rear of the train; being empty and smaller than the other cars they blew off the tracks even before the storm surge arrived, stopping the train from continuing past Islamorada. A close examination of photographs of the wreck show one box car still coupled to the last baggage car. The other two broke off completely and were apparently carried by the surge half-way across the key towards the bay. Two other boxcars were on a siding before the storm and ended up wedged against the sides of coaches 5 and 6, counting back from the locomotive. Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, Statements by Loftin, p. 504, Aitcheson, p. 506, and Branch, p. 515

- ↑ Scott Loftin, FEC co-receiver, concluded on Sept 6, 1935, that the delays likely saved the crew and passengers; if the train had arrived an hour earlier it would have been on Lower Matecumbe or the narrow Indian Key fill when the surge struck and destroyed. "From what we now know it seems that the men could not have been extracted from the camps unless the train had left Miami about 10:00 am." Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 504. HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ Testimonies of Davis (p. 538) and Sheeran (p. 931), VA Investigation, National Archives Building, Washington, DC

- ↑ St. Petersburg Times, Sept. 5, 1935, p. 1. "Storm Danger Fades Here, Damage Heavy". Google News

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 3, Testimony of J. Hardin Peterson HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 390, Letter Hines to Rankin.HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ New York Times, Aug. 8, 1935, p. 11, “4,000 Veterans Placed in Southern Camps”, NYT

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 364, Testimony of Frank Hines. HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 443, Testimony of Aubrey Williams. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ New York Times, Aug. 8, 1935, p. 11, “4,000 Veterans Placed in Southern Camps” NYT

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 365. HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 435. HathiTrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 49, Testimony of Julius Stone. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 435, Testimony of Aubrey Williams. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 445, Testimony of Aubrey Williams. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Time, Aug. 26, 1935, “Relief: Playgrounds for Derelicts”. Time Magazine

- ↑ NYT, Aug. 7, 1935, p. 1, “Veterans Find a 'Heaven' In Federal Camp in South”. NYT

- ↑ NYT, Aug 14, 1935, p. 1, “Bonus Army Digs Old 'Swimmin' Hole' as Rehabilitation”. NYT

- ↑ NYT, Aug. 16, 1935, p. 9, “Veterans' Camps to be Abandoned”. NYT

- ↑ St. Petersburg Times, Sept. 5, 1935, p. 1. "Storm Danger Fades Here, Damage Heavy". Google News

- ↑ The American Legion Monthly, Volume 19, No. 5 (November 1935), p. 28, "Rendezvous with Death" by Fred C. Painton American Legion Digital Archive

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 331. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 371. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Letter, Machlan to Hines, Sept. 16, 1935, VA Investigative Records, National Archives Building, Washington DC

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 332. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ NYT, Oct. 10, 1936, "'Transients' Lose Federal Aid Soon", p. E11

- ↑ NYT, Nov. 20, 1935, "WPA Speeds Work to 'Wartime Rush'", p. 2

- ↑ NYT, Sept. 5, 1935, "Defends Failure to Move Veterans; Hopkins Says Action Was Not Warranted by the Reports of Hurricane's Course", p. 9. NYT

- ↑ Leithiser Report, Sept. 19, 1935 Flickr

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 332.Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Hines to Col. McIntyre, Third Report on Evacuation of Veterans from Florida, Sept. 7, 1935, Hurricane Records, FDR Library

- ↑ Miami Daily News, Sept. 9, 1935, p. 8. Google News

- ↑ Plot Plan, Woodlawn Park Cemetery of Hurricane Victims of Keys September 2nd & 3rd 1935 with notes, VA Report of Investigation, National Archives Building, Washington , DC. Plot Plan

- ↑ Labor Day memorial at find a grave

- ↑ [Congressional Inquiry H.R. 9486]

- ↑ History of the Keys

- ↑ [Note: 1 man reported missing later identified as dead; 1 man not listed here among hurricane dead had died in an accident in August 1935]

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 332, Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, ps. 390 - 400. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Veterans Storm Relief Map

- ↑ American Red Cross, South Florida Division: Remembering the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane.

- ↑ http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/16158

- ↑ The New Masses, September 17, 1935, Pg 3

- ↑ Washington Post, Sept. 5, 1935, Editorial, "Ruin in the Veterans' Camps"

- ↑ Miami Daily News, Sept. 9, 1935, p. 1i, “Thousands Bow in Tribute Paid to Storm Dead.” Google News

- ↑ Report, Williams and Ijams to Roosevelt, Sept. 8, 1935, FDR Library. Flickr

- ↑ Telegram, Ijams to Hines, Sept. 9, 1935. Flickr

- ↑ Miami Daily News, September 9, 1935, p. 9, “Storm Deaths an Act of God, Says Williams”. Google News

- ↑ Telegram, Early to McIntyre, Sept. 10, 1935. Flickr

- ↑ Correspondence regarding letter from the Greater Miami Ministerial Association, Sept. 10, 1935. Flickr

- ↑ Letter, Kennamer to Jared, Sept. 12, 1935 Flickr

- ↑ List of Exhibits from D. W. Kennamer's Investigation of the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 Flickr

- ↑ Administrative letters and findings from D. W. Kennamer's Investigation of the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. Flickr

- ↑ Memo dated Oct. 5, 1935 and General Comments by D. W. Kennamer Flickr

- ↑ Draft Report to the President regarding the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, ca. Dec. 1935. Flickr

- ↑ Memo, Ijams to Hines, Jan. 10, 1936. Flickr

- ↑ VA letter denying release of Kennamer's report, Mar. 26, 1968.Letter

- ↑ Miami Daily News, Jan. 27, 1936, p.1. Google News

- ↑ Florida Hurricane Disaster Hearings, p. 334. Hathitrust Digital Library

- ↑ Report of Special Investigation Committee, Florida Hurricane Disaster to National Executive Committee, The American Legion, by Quimby Melton,Georgia, Chairman, November 1, 1935, p. 6. Flickr

- ↑ Draft letter, Roosevelt to Murphy, November 14, 1935. Flickr

- ↑ Florida Keys Memorial Flickr

- 1 2 3 Matecumbe Monument Honors Victims of 1935 Hurricane, The Palm Beach Post. Page 10 - Nov 15, 1937 Flickr

- ↑ Letter, Hines to Mills, Nov. 2, 1937 Flickr

- ↑ Letter, Hines to Williams, June 24, 1937 Flickr

- ↑ Veterans Storm Relief Map

- ↑ 38 U.S. Code § 2306 (b) Cornell Law

- ↑ Miami Daily News, February 19, 1939, p. 1 and 10, Roosevelt. Google News

- ↑ FDR Presidential Library. Day by Day, February 18, 1939. FDR Library

- ↑ FDR Presidential Library, Press Conference #526, February 18, 1939, p. 152. FDR Library

- ↑ Miami Daily News, February 16, 1939, p.1, Florida Awaits Train Bearing Roosevelt Here. Google News

- ↑ National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places, Reference No. 95000238

- ↑ Heritage Monument Trail Plaque at Florida Keys Memorial

Heritage Monument Trail Plaque

Heritage Monument Trail Plaque - ↑ Matecumbe Historical Trust, Calendar of Events for May and September

- ↑ Resolution, Harvey W. Seeds Post No. 29, American Legion, Jan. 31, 1936 Resolution

- ↑ Letter, Wickenden to Trammell, March 9, 1936 Letter

- ↑ Inscription on Woodlawn Park Cemetery Hurricane Memorial

Woodlawn Hurricane Memorial

Woodlawn Hurricane Memorial - ↑ Find a grave

- ↑ Moore grave site Arlington Find a Grave

- ↑ Preservationist Jerry Wilkinson visits unmarked Miami graves of soldiers killed in the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane You Tube

- ↑ Main grave site Arlington NC Find a Grave

- ↑ Injured Recount Camp Gale Horror, by the Associated Press, New York Times, September 5, 1935, Pg. 3: “Dr. Lassiter Alexander, medical officer at Camp No. 1, Snake Creek, who had injuries to his back, related: … One of those killed in the collapse of the Snake Creek Hotel was Dr. E. [sic] C. Main, medical director of the camp, who lost his life before my eyes.”

- ↑ Sacco Report, Pg. 2, Body 6-A, Flickr

- ↑ Veterans Key, U.S. Board on Geographic Names

- ↑ Veterans Key Images Flickr

- ↑ 38 CFR 38.632 Cornell Law

- ↑ Hearing before the House Subcommittee on Disability Assistance and Memorial Affairs, Oct. 30, 2013 House Archives Archived 2015-06-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ AO95 - Proposed Rule - Applicants for VA Memorialization Benefits regulations.gov

External links

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory

- Images of historic Florida Hurricanes (State Archives of Florida)

- Keys Historeum, Historical Preservation Society of the Upper Keys

- Major Daniel C. Main killed in Hurricane

- Monroe County listings at National Register of Historic Places

- Florida Keys Memorial at Florida's Office of Cultural and Historical Programs

- 1935 Newspaper reports

- Link comparison of 1935 Hurricane and Hurricane Katrina

- Find A Grave 1935 Hurricane victims of 1935 Labor day memorial at Islamorada

- Find A Grave 1935 Hurricane Victims buried at Woodlawn Park North Cemetery and Mausoleum

- Horrific Florida Keys Hurricane, Labor Day 1935 Biot Report #631: July 05, 2009

- Florida Hurricane Disaster, Hearings Before the Committee on World War Veterans' Legislation, House of Representatives, Seventy-Fourth Congress, Second Session, On H. R. 9486, A Bill for the Relief of Widows, Children, and Dependent Parents of World War Veterans Who Died as the Result of the Florida Hurricane at Windley Island and Matecumbe Keys on September 2, 1935; U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1936. HathiTrust Digital Library

- "Who Murdered the Vets? A First-hand Report on the Florida Hurricane" by Ernest Hemingway. The New Masses, September 17, 1935

- Keys remembers killer storm 80 years later 2016