United States presidential election, 1864

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 233 electoral votes of the Electoral College 117 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout |

73.8%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

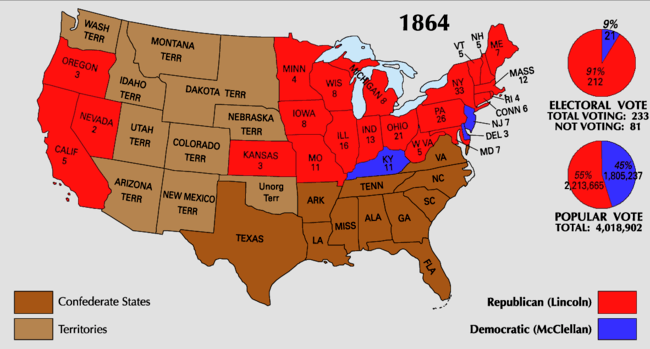

Presidential election results map. light red denotes states won by Lincoln/Johnson, blue denotes those won by McClellan/Pendleton, and brown denotes Confederate states; two Confederate states (Louisiana and Tennessee) were controlled by the Union by 1864 and held elections (although their electors were not ultimately counted). Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1864 was the 20th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 1864. In this match, incumbent president Republican Abraham Lincoln ran for reelection against Democratic candidate George B. McClellan, who tried to portray himself to the voters as the "peace candidate" who wanted to bring the American Civil War to a speedy end. Lincoln was re-elected president by a landslide in the Electoral College.

Since the election of 1860, the Electoral College had expanded with the admission of Kansas, West Virginia, and Nevada as free-soil states. As the Civil War was still raging, no electoral votes were counted from any of the eleven southern states that had joined the Confederate States of America.[2]

Lincoln won by more than 400,000 popular votes, partly as a result of the recent Union victory at the Battle of Atlanta[3] and was the first president to be re-elected since Democrat Andrew Jackson in 1832. The second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln took place on March 4, 1865, but he was assassinated on April 15, 1865, only 42 days later. Lincoln's second term is the second shortest term served by any U.S. president, next to the 31-day presidency of William Henry Harrison.

Background

The Presidential election of 1864 took place during the American Civil War. According to the Miller Center for the study of the presidency, the election was noteworthy for occurring at all, an unprecedented democratic exercise in the midst of a civil war.[4]

A group of Republican dissidents who called themselves Radical Republicans formed a party named the Radical Democracy Party and nominated John C. Frémont as their candidate for president. Frémont later withdrew and endorsed Lincoln. In the Border States, War Democrats joined with Republicans as the National Union Party, with Lincoln at the head of the ticket.[5] The National Union Party was a temporary name used to attract War Democrats and Border State Unionists who would not vote for the Republican Party. It faced off against the regular Democratic Party, including Peace Democrats.

Nominations

The 1864 presidential election conventions of the parties are considered below in order of the party's popular vote.

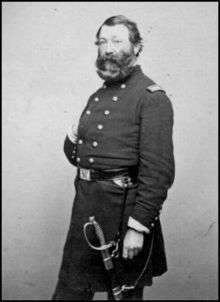

National Union Party nomination

National Union candidates:

- Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States

- Ulysses S. Grant, Commanding General from Illinois

National Union Party Presidential candidates gallery

National Union Party Vice-Presidential candidates gallery

Former Senator Andrew Johnson from Tennessee

Former Senator Daniel Dickinson from New York

General Lovell Rousseau from Kentucky

Temporary split in the Republican Party

As the Civil War progressed, political opinions within the Republican Party began to diverge. Senators Charles Sumner and Henry Wilson from Massachusetts wanted the Republican Party to advocate constitutional amendments to prohibit slavery and guarantee racial equality before the law. Initially, not all northern Republicans supported such measures.

Democratic leaders hoped that the radical Republicans would put forth their own ticket in the election. The New York World, particularly interested in undermining the National Union Party, ran a series of articles predicting a delay for the National Union Convention until late in 1864 to allow Frémont time to collect delegates to win the nomination. Frémont supporters in New York City established a newspaper called the New Nation, which declared in one of its initial issues that the National Union Convention would be a "nonentity".

National Union Party

Before the election, some War Democrats joined the Republicans to form the National Union Party.[6] With the outcome of the Civil War still in doubt, some political leaders, including Salmon P. Chase, Benjamin Wade, and Horace Greeley, opposed Lincoln's re-nomination on the grounds that he could not win. Chase himself became the only candidate to contest Lincoln's re-nomination actively, but he withdrew in March when a slew of Republican officials, including some within the state of Ohio upon whom Chase's campaign depended, endorsed Lincoln for re-nomination. Lincoln was still popular with most members of the Republican Party, and the National Union Party nominated him for a second term as president at their convention in Baltimore, Maryland, on June 7–8, 1864.[7] The party platform included these goals:

...pursuit of the war until the Confederacy surrendered unconditionally; a constitutional amendment for the abolition of slavery; aid to disabled Union veterans; continued European neutrality; enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine; encouragement of immigration; and construction of a transcontinental railroad. It also praised the use of black troops and Lincoln's management of the war.[8]

Andrew Johnson, the former senator from and current military governor of Tennessee, was named as Lincoln's vice presidential running-mate. Others who were considered for the nomination, at one point or another, were former Senator Daniel Dickinson, Major General Benjamin Butler, Major General William Rosecrans, Joseph Holt, and former Treasury Secretary and Senator John Dix.

Democratic Party nomination

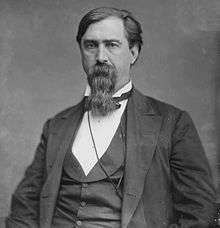

Democratic Presidential candidates:

- George B. McClellan, General from New Jersey

- Thomas H. Seymour, Former Governor of Connecticut

Democratic Party candidates gallery

Democratic Party Vice-Presidential candidates gallery

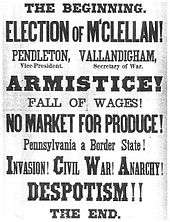

The Democratic Party was bitterly split between War Democrats and Peace Democrats, a group further divided among competing factions. Moderate Peace Democrats who supported the war against the Confederacy, such as Horatio Seymour, were preaching the wisdom of a negotiated peace. After the Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, moderate Peace Democrats proposed a negotiated peace that would secure Union victory. They believed this was the best course of action, because an armistice could finish the war without devastating the South.[9] Radical Peace Democrats known as Copperheads, such as Thomas H. Seymour, declared the war to be a failure and favored an immediate end to hostilities without securing Union victory.[10]

George B. McClellan vied for the presidential nomination. Additionally, friends of Horatio Seymour insisted on placing his name before the convention, which was held in Chicago, Illinois, on August 29–31, 1864. But on the day before the organization of that body, Horatio Seymour announced positively that he would not be a candidate.

Since the Democrats were divided by issues of war and peace, they sought a strong candidate who could unify the party. The compromise was to nominate pro-war General George B. McClellan for president and anti-war Representative George H. Pendleton for vice-president. McClellan, a War Democrat, was nominated over the Copperhead Thomas H. Seymour. Pendleton, a close associate of the Copperhead Clement Vallandigham, balanced the ticket, since he was known for having strongly opposed the Union war effort.[11] The convention then adopted a peace platform[12] — a platform McClellan personally rejected.[13] McClellan supported the continuation of the war and restoration of the Union, but the party platform, written by Vallandigham, opposed this position.

Radical Democracy Party nomination

Radical Democracy Party candidates gallery

Former Senator John C. Frémont from California

(Withdrew Sep 22, 1864)

Radical Democracy Party Vice-Presidential candidates gallery

General John Cochrane from New York

The Radical Democracy Convention assembled in Ohio with delegates arriving on May 29, 1864. The New York Times reported that the hall which the convention organizers had planned to use had been double-booked by an opera troupe. Almost all delegates were instructed to support Frémont, with a major exception being the New York delegation, which was composed of War Democrats who supported Ulysses S. Grant. Various estimates of the number of delegates were reported in the press; the New York Times reported 156 delegates, but the number generally reported elsewhere was 350 delegates. The delegates came from 15 states and the District of Columbia. They adopted the name "Radical Democracy Party."[14]

A supporter of Grant was appointed chairman. The platform was passed with little discussion, and a series of resolutions that bogged down the convention proceedings were voted down decisively. The convention nominated Frémont for president, and he accepted the nomination on June 4, 1864. In his letter, he stated that he would step aside if the National Union Convention would nominate someone other than Lincoln. John Cochrane was nominated for vice-president.[15]

General election

%2C_by_Thomas_Nast.png)

The 1864 election was the first time since 1812 that a presidential election took place during a war.

For much of 1864, Lincoln himself believed he had little chance of being re-elected. Confederate forces had triumphed at the Battle of Mansfield, the Battle of the Crater, and the Battle of Cold Harbor. In addition, the war was continuing to take a very high toll in terms of casualties. The prospect of a long and bloody war started to make the idea of "peace at all cost" offered by the Copperheads look more desirable. Because of this, McClellan was thought to be a heavy favorite to win the election. Unfortunately for Lincoln, Frémont's campaign got off to a good start.

However, several political and military events eventually made Lincoln's re-election inevitable. In the first place, the Democrats had to confront the severe internal strains within their party at the Democratic National Convention. The political compromises made at the Democratic National Convention were contradictory and made McClellan's efforts to campaign seem inconsistent.

Secondly, the Democratic National Convention influenced Frémont's campaign. Frémont was appalled at the Democratic platform, which he described as "union with slavery." After three weeks of discussions with Cochrane and his supporters, Frémont withdrew from the race in September 1864. In his statement, Frémont declared that winning the Civil War was too important to divide the Republican vote. Although he still felt that Lincoln was not going far enough, the defeat of McClellan was of the greatest necessity. General Cochrane, who was a War Democrat, agreed and withdrew with Frémont. Frémont also brokered a political deal in which Lincoln removed U.S. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair from office. McClellan's chances of victory faded after Frémont withdrew from the presidential race.

Lastly, with the fall of Atlanta on September 2, there was no longer any question that a Union military victory was inevitable and close at hand.

In the end, the Union Party mobilized the full strength of both the Republicans and the War Democrats under the its slogan "Don't change horses in the middle of a stream." It was energized as Lincoln made emancipation the central issue, and state Republican parties stressed the perfidy of the Copperheads.[16]

Results

Because eleven Southern states had declared secession from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America, only twenty-five states participated in the election. Three new states participated for the first time: Kansas, West Virginia, and Nevada. The reconstructed portions of Louisiana and Tennessee chose presidential electors, although Congress did not count their votes.

McClellan won just three states: Kentucky, Delaware, and his home state of New Jersey. Lincoln won in every state he carried in 1860 except New Jersey, and also carried a state won four years earlier by Stephen Douglas (Missouri), one carried by John C. Breckinridge (Maryland) and all three newly admitted states (Kansas, Nevada and West Virginia). Altogether, 212 electoral votes were counted in Congress for Lincoln - more than enough to win the presidency even if all of the states in rebellion had participated.

Lincoln was highly popular with soldiers and they in turn recommended him to their families back home.[17][18] The following states allowed soldiers to cast ballots: California, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin. Out of the 40,247 army votes cast, Lincoln received 30,503 (75.8%) and McClellan 9,201 (22.9%), with the rest (543 votes) scattering (1.3%). Only soldiers from Kentucky gave McClellan a majority of their votes, and he carried the army vote in the state by a vote of 2,823 (70.3%) to 1,194 (29.7%).[19]

Of the 1,129 counties making returns, Lincoln won in 728 (64.48%), while McClellan carried 400 (35.43%). One county (0.09%) in Iowa split evenly between Lincoln and McClellan.

This was the last election when the Republicans won Maryland until 1896.[20]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a) | Electoral vote(a), (b), (c) |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote(a), (b), (c) | ||||

| Abraham Lincoln (Incumbent) | National Union | Illinois | 2,218,388 | 55.0% | 212(b) | Andrew Johnson | Tennessee | 212(b) |

| George Brinton McClellan | Democratic | New Jersey | 1,812,807 | 45.0% | 21 | George Hunt Pendleton | Ohio | 21 |

| Other | 692 | 0.0% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 4,031,887 | 100% | 233(b) | 233(b) | ||||

| Needed to win | 117(b) | 117(b) | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1864 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

(a) The states in rebellion did not participate in the election of 1864.

(b) The electors from Tennessee and Louisiana were rejected. Had they not been rejected, Lincoln would have garnered 229 electoral votes out of a total of 250.

(c) One elector from Nevada did not vote

Geography of results

Cartographic gallery

Map of presidential election results by county

Map of presidential election results by county Results explicitly indicating the percentage for the National Union candidate in each county

Results explicitly indicating the percentage for the National Union candidate in each county Results explicitly indicating the percentage for the Democratic candidate in each county

Results explicitly indicating the percentage for the Democratic candidate in each county Results explicitly indicating the percentage for "other" candidate(s) in each county

Results explicitly indicating the percentage for "other" candidate(s) in each county Cartogram of presidential election results by county

Cartogram of presidential election results by county Cartogram of National Union presidential election results by county

Cartogram of National Union presidential election results by county Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

Source: Data from Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential ballots, 1836–1892 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp. 247–57.

| States won by Lincoln/Johnson | ||||||||||||||

| States won by McClellan/Pendleton | ||||||||||||||

| Abraham Lincoln National Union |

George B. McClellan Democratic |

State Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | ||||||

| California | 5 | 62,053 | 58.6 | 5 | 43,837 | 41.4 | - | 105,890 | 100 | |||||

| Connecticut | 6 | 44,673 | 51.4 | 6 | 42,285 | 48.6 | - | 86,958 | 100 | |||||

| Delaware | 3 | 8,155 | 48.2 | - | 8,767 | 51.8 | 3 | 16,922 | 100 | |||||

| Illinois | 16 | 189,512 | 54.4 | 16 | 158,724 | 45.6 | - | 348,236 | 100 | |||||

| Indiana | 13 | 149,887 | 53.5 | 13 | 130,230 | 46.5 | - | 280,117 | 100 | |||||

| Iowa | 8 | 83,858 | 63.1 | 8 | 49,089 | 36.9 | - | 132,947 | 100 | |||||

| Kansas | 3 | 17,089 | 81.7 | 3 | 3,836 | 18.3 | - | 21,580 | 100 | |||||

| Kentucky | 11 | 27,787 | 30.2 | - | 64,301 | 69.8 | 11 | 92,088 | 100 | |||||

| Maine | 7 | 67,805 | 59.1 | 7 | 46,992 | 40.9 | - | 114,797 | 100 | |||||

| Maryland | 7 | 40,153 | 55.1 | 7 | 32,739 | 44.9 | - | 72,892 | 100 | |||||

| Massachusetts | 12 | 126,742 | 72.2 | 12 | 48,745 | 27.8 | - | 175,487 | 100 | |||||

| Michigan | 8 | 91,133 | 55.1 | 8 | 74,146 | 44.9 | - | 165,279 | 100 | |||||

| Minnesota | 4 | 25,031 | 59 | 4 | 17,376 | 41 | - | 42,407 | 100 | |||||

| Missouri | 11 | 72,750 | 69.7 | 11 | 31,596 | 30.3 | - | 104,346 | 100 | |||||

| Nevada | 2 | 9,826 | 59.8 | 2 | 6,594 | 40.2 | - | 16,420 | 100 | |||||

| New Hampshire | 5 | 36,596 | 52.6 | 5 | 33,034 | 47.4 | - | 69,630 | 100 | |||||

| New Jersey | 7 | 60,724 | 47.2 | - | 68,020 | 52.8 | 7 | 128,744 | 100 | |||||

| New York | 33 | 368,735 | 50.5 | 33 | 361,986 | 49.5 | - | 730,721 | 100 | |||||

| Ohio | 21 | 265,674 | 56.4 | 21 | 205,609 | 43.6 | - | 471,283 | 100 | |||||

| Oregon | 3 | 9,888 | 53.9 | 3 | 8,457 | 46.1 | - | 18,345 | 100 | |||||

| Pennsylvania | 26 | 296,292 | 51.6 | 26 | 277,443 | 48.4 | - | 573,735 | 100 | |||||

| Rhode Island | 4 | 14,349 | 62.2 | 4 | 8,718 | 37.8 | - | 23,067 | 100 | |||||

| Vermont | 5 | 42,419 | 76.1 | 5 | 13,321 | 23.9 | - | 55,750 | 100 | |||||

| West Virginia | 5 | 23,799 | 68.2 | 5 | 11,078 | 31.8 | - | 34,877 | 100 | |||||

| Wisconsin | 8 | 83,458 | 55.9 | 8 | 65,884 | 44.1 | - | 149,342 | 100 | |||||

| TOTALS: | 233 | 2,218,388 | 55 | 212 | 1,812,807 | 45 | 21 | 4,031,887 | 100 | |||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1864 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

States with close margins of victory

States in red were won by Republican Abraham Lincoln; states in blue were won by Democrat George B. McClellan.

Below is the state where the margin of victory was under 1%. This closely won state totaled 33 electoral votes:

- New York 0.92% (33 electoral votes)

Below are the states where the margin of victory was under 5%. These closely won states totaled 35 electoral votes:

- Connecticut 2.76% (6 electoral votes)

- Pennsylvania 3.51% (26 electoral votes)

- Delaware 3.62% (3 electoral votes)

See also

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- Electoral history of Abraham Lincoln

- History of the United States (1849–1865)

- Second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln

- Third Party System

- United States House elections, 1864

Footnotes

- ↑ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- 1 2 Elections were held in the Union-occupied military districts in the states of Louisiana and Tennessee, but no electoral votes were counted from them. Including these two states increases Lincoln's states carried from 22 to 24 and the total participating states from 25 to 27. Donald, David Herbert; Baker, Jean Harvey; Holt, Michael F. (2001). The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 427.

- ↑ Davis, William C. (1999). Lincoln's Men: How President Lincoln became Father to an Army and a Nation. Simon and Schuster. p. 211. ISBN 0-684-83337-9. The public entrusted Lincoln with another term in spite of widespread revulsion at the death toll in the Wilderness Campaign. Republicans had found success in gubernatorial races in Ohio and Pennsylvania by attracting the votes of furloughed soldiers. In order to copy the same success nationally, thirteen Union states allowed their citizens serving as soldiers in the field to cast ballots. Four additional Union states allowed "proxy" absentee voting. "By margins of three to one or better, the soldiers [lined up] behind Lincoln." In every state, those returning home influenced their friends and family. For an alternative account of army voting, see W. Dean Burnham, "Presidential Ballots: 1836–1892", pgs. 260–883. Out of the 40,247 Army votes cast in seven states, Lincoln carried six of them with 30,503 votes (75.8%).

- ↑ "Abraham Lincoln: Campaigns and Elections". American President: A Reference Resource. University of Virginia. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ↑ Martis, Kenneth C., "Atlas of the Political Parties in the United States Congress, 1789–1989" ISBN 0-02-920170-5 p. 117. Altogether they elected 9 Senators and 25 Representatives in Missouri, Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware.

- ↑ World Book

- ↑ The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents

- ↑ "HarpWeek | Elections | 1864 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- ↑ They Also Ran

- ↑ The American Pageant

- ↑ George Pendleton. Ohio History Central (May 23, 2013). Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ "Democratic Party Platforms: 1864 Democratic Party Platform".

- ↑ "George B. McClellan". Ohio History Central. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ↑ "HarpWeek: Explore History, 1864: Lincoln v. McClellan". Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ↑ US President – IR Convention Race – May 31, 1864. Our Campaigns (January 13, 2008). Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ Randall, J. G.; Current, Richard (1955). Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure. p. 307.

- ↑ Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (University Press of Kansas, 1994) pp 274–293

- ↑ Oscar O. Winther, "The Soldier Vote in the Election of 1864," New York History (1944) 25: 440–58

- ↑ Presidential Ballots: 1836–1892, W. Dean Burnham, pgs. 260–883

- ↑ Counting the Votes; Maryland

Further reading

- Balsamo, Larry T. "'We Cannot Have Free Government without Elections': Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864", Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (2001): 181-199.

- Dudley, Harold M. "The Election of 1864," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 18, No. 4 (Mar. 1932), pp. 500–518 in JSTOR

- Fehrenbacher, Don E. "The Making of a Myth: Lincoln and the Vice-Presidential Nomination in 1864". Civil War History 41.4 (1995): 273-290.

- Long, David E. Jewel of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln's Re-election and the End of Slavery (1994).

- Merrill, Louis Taylor "General Benjamin F. Butler in the Presidential Campaign of 1864." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 33 (March 1947): 537–570. in JSTOR

- Nelson, Larry E. Bullets, Ballots, and Rhetoric: Confederate Policy for the United States Presidential Contest of 1864 University of Alabama Press, 1980.

- Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: The War for the Union vol 8 (1971).

- Newman, Leonard. "Opposition to Lincoln in the Elections of 1864," Science & Society, vol. 8, no. 4 (Fall 1944), pp. 305–327. In JSTOR.

- Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (University Press of Kansas, 1994) pp 274–293.

- James G. Randall and Richard N. Current. Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure. Vol. 4 of Lincoln the President. 1955.

- Vorenberg, Michael. "'The Deformed Child': Slavery and the Election of 1864" Civil War History 2001 47(3): 240–257.

- Jack Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln: The Battle for the 1864 Presidency (1998).

- White, Jonathan W. "Canvassing the Troops: the Federal Government and the Soldiers' Right to Vote" Civil War History 2004 50(3): 291–317.

- White, Jonathan W. Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2014).

- Winther, Oscar O. "The Soldier Vote in the Election of 1864," New York and HistoryPages and do (1944) 25: 440–458.

External links

- Leip, Dave. "1864 Presidential Election – Home States". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- 1864 popular vote by counties

- 1864 State-by-state popular results

- Transcript of the 1864 Democratic Party Platform

- Harper's Weekly – Overview

- more from Harper's Weekly

- How close was the 1864 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Presidential Election of 1864: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Election of 1864 in Counting the Votes