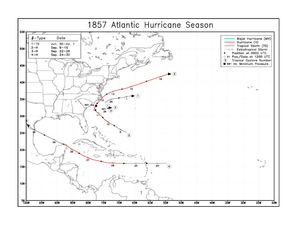

1857 Atlantic hurricane season

| 1857 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 30, 1857 |

| Last system dissipated | September 30, 1857 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Two and Four |

| • Maximum winds | 105 mph (165 km/h) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 424 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

|

| |

The 1857 Atlantic hurricane season was the earliest season documented by HURDAT – the official Atlantic hurricane database – to feature no major hurricane.[nb 1] A total of four tropical cyclones were observed during the season, three of which strengthened into hurricanes. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea are known, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 has been estimated.[2] Additionally, documentation by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz included a fifth tropical cyclone near Port Isabel, Texas;[3] this storm has since been removed from HURDAT as it was likely the same system as the fourth tropical cyclone.[4]

The first storm was tracked beginning on June 30 offshore North Carolina. It moved eastward and was last noted on the following day. However, no tropical cyclones were reported in the remainder of July or August. Activity resume when another tropical storm was located southeast of the Bahamas on September 6. It intensified into a hurricane before making landfall in North Carolina and was last noted over the north Atlantic Ocean on September 17. The SS Central America sank offshore, drowning 424 passengers and crew members. Another hurricane may have existed east of South Carolina between September 22 and October 26, though little information is available. The final documented tropical cyclone was initially observed east of Lesser Antilles on September 24. It traversed the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, striking the Yucatán Peninsula and later Port Isabel, Texas. The storm dissipated on September 30. In Texas, damage was reported in several towns near the mouth of the Rio Grande River.

The season's activity was reflected with a low accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 43.[1] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. ACE is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 34 knots (39 mph, 63 km/h) or tropical storm strength.[5]

Systems

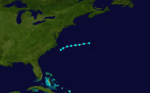

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 30 – July 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) |

The ship Star of the South experienced heavy gales offshore the East Coast of the United States on June 30.[3] HURDAT lists the first tropical cyclone of the season beginning at 0000 UTC, while located about 100 miles (160 km) southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.[6] The storm moved slightly north of due east with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[6] It was last noted about 265 miles (425 km) north-northwest of Bermuda by the bark Virginia late on July 1.[3][6]

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 6 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 961 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm was first observed east of the Bahamas on September 6. It moved slowly northwestward towards the coast of the United States and attained hurricane strength early on September 9. The cyclone continued travelling northwest along the US coast, becoming a Category 2 hurricane whilst off the coast of Georgia on September 11. On September 13 the cyclone made landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina, but then quickly weakened to a tropical storm and turned eastward into the Atlantic on September 14. Throughout September 15, whilst over water, the storm regained hurricane strength and continued northward before becoming extratropical in the mid-Atlantic on September 17.[6]

The hurricane caused much coastal damage particularly in the Cape Hatteras area during September 9 and September 10 and then to other parts of the North Carolina coast. Flooding was reported at New Bern.[7] Considerable wind damage also occurred. An article from the Wilmington Journal reported that, "It looked as though everything that could be blown down, was down. Fences were prostrated in all directions, and the streets filled with the limbs and bodies of trees up-rooted or twisted off.".[8] Several ships were caught in rough seas of the East Coast of the United States. The Norfolk was abandoned in pieces ten miles south of Chincoteague early on the morning of September 14.[3] Further south, on September 11, the hurricane struck the steamer Central America which sprung a leak and eventually sunk on the night of September 12 with the loss of 424 passengers and crew.[9] Also on board the ship were 30,000 pounds of gold, the loss of which contributed to the financial Panic of 1857.[10]

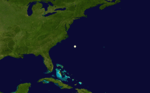

Hurricane Three

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 22 – September 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) |

Based on reports bark Aeronaut and the schooner Alabama indicating a severe gale, Partagas and Diaz identified a Category 1 hurricane about 405 miles (650 km) east of Charleston, South Carolina between September 22 and September 26.[3][6] Sustained wind speeds of 80 mph (130 km/h) were observed.[6] No evidence was found for a storm track so the hurricane was assigned a stationary position, at latitude 32.5°N, 3.5°W. Among the ships which encountered the hurricane was the brig Jerome Knight, which sprung a leak and sunk on the night of September 22.[3]

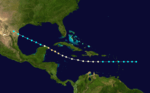

Hurricane Four

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) |

The final tropical cyclone was first observed at 0000 UTC on September 24, while located about 420 miles (680 km) east of Guadeloupe. Initially a tropical storm, it strengthened slightly before crossing the Leeward Islands on September 25.[6] In Guadeloupe, several ships at the port in Basseterre were swept out to sea.[3] Continuing eastward, the storm soon entered the Caribbean Sea. Early on September 26, the system strengthened into a hurricane.[6] By September 28, it was west of the Cayman Islands and had reached Category 2 strength. The storm weakened to a tropical storm after passing Cancun early on September 29 and impacted the Gulf coastline, near the United States–Mexico border, at that strength the next day before dissipating.[6] At Port Isabel, Texas, several hundred homes were swept away, and several towns near the mouth of the Rio Grande also sustained damage.[11]

See also

Notes

- ↑ A major hurricane is defined as a tropical cyclone reaching Category 3 or stronger on the modern day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale[1]

References

- 1 2 Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ Christopher W. Landsea (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 José Fernández-Partagás; Henry F. Diaz (1995). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources 1851-1880 Part 1: 1851-1870. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (April 11, 2017). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ James E. Hudgins (2000). Tropical cyclones affecting North Carolina since 1586 - An Historical Perspective (PDF). National Weather Service (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ Christopher W. Landsea; Craig Anderson; William Bredemeyer; Cristina Carrasco; Noel Charles; Michael Chenoweth; Gil Clark; Sandy Delgado; Jason Dunion; Ryan Ellis; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Steve Feuer; John Gamache; David Glenn; Andrew Hagen; Lyle Hufstetler; Cary Mock; Charlie Neumann; Ramon Perez Suarez; Ricardo Prieto; Jorge Sanchez-Sesma; Adrian Santiago; Jamese Sims; Donna Thomas; Lenworth Woolcock; Mark Zimmer (2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas (1996). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996: Cyclones with 25+ deaths. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ "Why Serious Coin Collectors Won’t Miss The Long Beach Expo". KIRO-TV. September 17, 2013. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ David W. Roth (February 4, 2010). Texas Hurricane History (PDF). Weather Prediction Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Weather Service. Retrieved March 5, 2014.