United States presidential election, 1840

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 294 electoral votes of the Electoral College 148 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout |

80.2%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Presidential election results map. Buff denotes states won by Harrison/Tyler, blue denotes those won by Van Buren & one of his three running mates. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

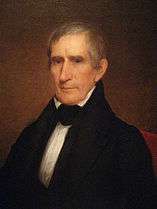

The United States presidential election of 1840 was the 14th quadrennial presidential election, held from Friday, October 30, to Wednesday, December 2, 1840. It saw President Martin Van Buren fight for re-election during a time of great economic depression against a Whig Party unified for the first time behind a single candidate: war hero William Henry Harrison. Under these circumstances, the Whigs easily defeated Van Buren.

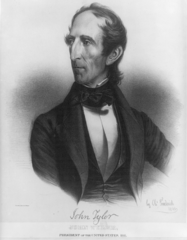

This election was unique in that electors cast votes for four men who had been or would become President of the United States: current President Martin Van Buren; President-elect William Henry Harrison; Vice President-elect John Tyler, who would succeed Harrison upon his death; and James K. Polk, who received one electoral vote for vice president, and who would succeed Tyler in 1845. 42.4% of the voting age population voted for Harrison, the highest percentage in the history of the United States up to that time.[1]

The 67-year-old Harrison was the oldest US president elected until Ronald Reagan, followed by Donald Trump in 2016. Harrison died little more than a month after his inauguration. His vice president John Tyler succeeded him, though no law at the time precisely outlined the details of presidential succession, and Tyler's precedent of assuming the full office was followed by convention until ratification of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967.

The choice of Tyler for Vice President proved to be disastrous for the Whigs. While Tyler had been a staunch supporter of Clay at the convention, he was a former Democrat and a passionate supporter of states' rights who blocked the Whigs' domestic legislative agenda after assuming the presidency. In September 1841, he was expelled from the party.

The Whigs would only elect one other president, in 1848: Zachary Taylor. Taylor would also die in office, only serving for little more than a year, and his successor Millard Fillmore destroyed the Whig image and the Whig Party dissolved after the election of 1852. President Martin Van Buren, who lost this election, attempted to regain the Democratic nomination in 1844. Upon losing, he won the nomination of the Free-Soil party in 1848.

Nominations

Democratic Party nomination

Democratic candidates

Van Buren, the incumbent president, was re-nominated in Baltimore in May 1840. The party refused to re-nominate his sitting vice president, Richard M. Johnson, but could not agree on an alternative, and so nominated no one. This remains the only time since the passage of the 12th Amendment, that a major party failed to do so. In the electoral college, the Democratic vice presidential votes were divided among Johnson, Littleton W. Tazewell, and James K. Polk.

Whig Party nomination

Whig candidates

Three years after Democrat Martin Van Buren was elected President in the election of 1836 over three Whig candidates, the Whigs met in national convention determined to unite behind a single candidate. The convention was chaired by Isaac C. Bates of Massachusetts and James Barbour of Virginia presided over the convention. The party nominated the popular retired general William Henry Harrison of Ohio for President, the most successful of the three Whig presidential candidates from the previous election. Harrison, though a slave-owner and aristocrat, was perceived as being simple and a commoner.[2] The convention nominated former Senator John Tyler from Virginia for Vice President. The two would go on to win the 1840 presidential election by defeating Van Buren.

Because Harrison (born in Virginia) was considered a Northerner (as a resident of Ohio), the Whigs needed to balance the ticket with a Southerner. They also sought a Clay supporter to help unite the party. Tyler was finally chosen by the convention after several Southern Clay supporters had been approached but refused. Tyler had previously been the running-mate of Hugh Lawson White and Willie Person Mangum during the four-way Whig campaign at the previous election.

Anti-Masonic Party nomination

After the negative views of Freemasonry among a large segment of the public began to wane in the mid 1830s, the Anti-Masonic Party had begun to disintegrate. Its leaders began to move one by one to the Whig party. Party leaders met in September 1837 in Washington, D.C., and agreed to maintain the party. The third Anti-Masonic Party National Convention was held in Philadelphia on November 13-14, 1838. By this time, the party had been almost entirely supplanted by the Whigs. The delegates unanimously voted to nominate William Henry Harrison for president (who the party had supported for president the previous election along with Francis Granger for Vice President) and Daniel Webster for Vice President. However, when the Whig National Convention nominated Harrison with John Tyler as his running mate, the Anti-Masonic Party did not make an alternate nomination and ceased to function and was fully absorbed into the Whigs by 1840.

| Presidential vote | Vice Presidential vote | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| William Henry Harrison | 119 | Daniel Webster | 119 |

Liberty Party nomination

The Liberty Party was announced in November 1839, and first gathered in Warsaw, New York. Its first national convention took place in Arcade on April 1, 1840.

The Liberty Party nominated James G. Birney, a Kentuckian, former slaveholder, and prominent abolitionist, for President while Thomas Earle of Pennsylvania was selected as his running mate.

General election

Campaign

In the wake of the Panic of 1837, Van Buren was widely unpopular, and Harrison, following Andrew Jackson's strategy, ran as a war hero and man of the people while presenting Van Buren as a wealthy snob living in luxury at the public expense. Although Harrison was comfortably wealthy and well educated, his "log cabin" image caught fire, sweeping all sections of the country.

Harrison avoided campaigning on the issues, with his Whig Party attracting a broad coalition with few common ideals. The Whig strategy overall was to win the election by avoiding discussion of difficult national issues such as slavery or the national bank and concentrate instead on exploiting dissatisfaction over the failed policies of the Van Buren administration with colorful campaigning techniques.

Log cabin campaign of William Henry Harrison

Harrison was the first president to campaign actively for office. He did so with the slogan "Tippecanoe and Tyler too". Tippecanoe referred to Harrison's military victory over a group of Shawnee Indians at a river in Indiana called Tippecanoe in 1811. For their part, Democrats laughed at Harrison for being too old for the presidency, and referred to him as "Granny", hinting that he was senile. Said one Democratic newspaper: "Give him a barrel of hard cider, and ... a pension of two thousand [dollars] a year ... and ... he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin."

Whigs took advantage of this quip and declared that Harrison was "the log cabin and hard cider candidate", a man of the common people from the rough-and-tumble West. They depicted Harrison's opponent, President Martin Van Buren, as a wealthy snob who was out of touch with the people. In fact, it was Harrison who came from a family of wealthy planters, while Van Buren's father was a tavernkeeper. Harrison however moved to the frontier and for years lived in a log cabin, while Van Buren had been a well-paid government official.

Nonetheless, the election was held during the worst economic depression in the nation's history, and voters blamed Van Buren, seeing him as unsympathetic to struggling citizens. Harrison campaigned vigorously and won.

Results

Harrison won the support of western settlers and eastern bankers alike. The extent of Van Buren's unpopularity was evident in Harrison's victories in New York (the president's home state) and in Tennessee, where Andrew Jackson himself came out of retirement to stump for his former vice-president.

Few Americans were surprised when Van Buren lost by an electoral vote of 234 to 60. But many were amazed by the close popular vote. Of 2,400,000 votes cast, Van Buren lost by only 146,000. Given the circumstances, it is surprising that the Democrats did as well as they did.[3]

Of the 1,179 counties/independent cities making returns, Harrison won in 699 (59.29%) while Van Buren carried 477 (40.46%). Three counties (0.25%) in the South split evenly between Harrison and Van Buren.

Harrison's victory won him precious little time as chief executive of the United States. After giving the longest inauguration speech in U.S. history (about 1 hour, 45 minutes, in cool weather), Harrison served only one month as president before dying of pneumonia on April 4, 1841. This was the first election in US history in which a candidate won more than a million popular votes.

This was the last election where Indiana voted for the Whigs. It is also the only election where the Whigs won Maine, Michigan, and Mississippi. The election was also the last time that Mississippi voted against the Democrats until 1872, the last in which Indiana did so until 1860 and the last in which Maine and Michigan did so until 1856.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a) | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| William Henry Harrison | Whig | Ohio | 1,275,390 | 52.9% | 234 | John Tyler | Virginia | 234 |

| Martin Van Buren | Democratic | New York | 1,128,854 | 46.8% | 60 | Richard Mentor Johnson | Kentucky | 48 |

| Littleton W. Tazewell | Virginia | 11 | ||||||

| James Knox Polk | Tennessee | 1 | ||||||

| James G. Birney | Liberty | New York | 6,797 | 0.3% | 0 | Thomas Earle | Pennsylvania | 0 |

| Other | 767 | 0.0% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 2,411,808 | 100% | 294 | 294 | ||||

| Needed to win | 148 | 148 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1840 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

(a) The popular vote figures exclude South Carolina where the Electors were chosen by the state legislature rather than by popular vote.

Geography of results

Cartographic gallery

Map of presidential election results by county

Map of presidential election results by county Map of Whig presidential election results by county

Map of Whig presidential election results by county Map of Democratic presidential election results by county

Map of Democratic presidential election results by county Map of Liberty presidential election results by county

Map of Liberty presidential election results by county Map of "Other" presidential election results by county

Map of "Other" presidential election results by county Cartogram of presidential election results by county

Cartogram of presidential election results by county Cartogram of Whig presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Whig presidential election results by county Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county Cartogram of Liberty presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Liberty presidential election results by county Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

Source: Data from Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential ballots, 1836-1892 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp 247-57.

| William Henry Harrison Whig |

Martin Van Buren Democratic |

James G. Birney Liberty |

State Total | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | |||||

| Alabama | 7 | 28,515 | 45.62 | - | 33,996 | 54.38 | 7 | no ballots | 62,511 | AL | ||||||

| Arkansas | 3 | 5,160 | 43.58 | - | 6,679 | 56.42 | 3 | no ballots | 11,839 | AR | ||||||

| Connecticut | 8 | 31,598 | 55.55 | 8 | 25,281 | 44.45 | - | no ballots | 56,879 | CT | ||||||

| Delaware | 3 | 5,967 | 54.99 | 3 | 4,872 | 44.89 | - | no ballots | 10,852 | DE | ||||||

| Georgia | 11 | 40,339 | 55.78 | 11 | 31,983 | 44.22 | - | no ballots | 72,322 | GA | ||||||

| Illinois | 5 | 45,574 | 48.91 | - | 47,441 | 50.92 | 5 | 160 | 0.17 | - | 93,175 | IL | ||||

| Indiana | 9 | 65,302 | 55.86 | 9 | 51,604 | 44.14 | - | no ballots | 116,906 | IN | ||||||

| Kentucky | 15 | 58,488 | 64.20 | 15 | 32,616 | 35.80 | - | no ballots | 116,865 | KY | ||||||

| Louisiana | 5 | 11,296 | 59.73 | 5 | 7,616 | 40.27 | - | no ballots | 18,912 | LA | ||||||

| Maine | 10 | 46,612 | 50.23 | 10 | 46,190 | 49.77 | - | no ballots | 92,802 | ME | ||||||

| Maryland | 10 | 33,528 | 53.83 | 10 | 28,752 | 46.17 | - | no ballots | 62,280 | MD | ||||||

| Massachusetts | 14 | 72,852 | 57.44 | 14 | 52,355 | 41.28 | - | 1,618 | 1.28 | - | 126,825 | MA | ||||

| Michigan | 3 | 22,933 | 51.71 | 3 | 21,096 | 47.57 | - | 321 | 0.72 | - | 44,350 | MI | ||||

| Mississippi | 4 | 19,515 | 53.43 | 4 | 17,010 | 46.57 | - | no ballots | 36,525 | MS | ||||||

| Missouri | 4 | 22,954 | 43.37 | - | 29,969 | 56.63 | 4 | no ballots | 52,923 | MO | ||||||

| New Hampshire | 7 | 26,310 | 43.88 | - | 32,774 | 54.66 | 7 | 872 | 1.45 | - | 59,956 | NH | ||||

| New Jersey | 8 | 33,351 | 51.74 | 8 | 31,034 | 48.15 | - | 69 | 0.11 | - | 64,454 | NJ | ||||

| New York | 42 | 226,001 | 51.18 | 42 | 212,733 | 48.18 | - | 2,809 | 0.64 | - | 441,543 | NY | ||||

| North Carolina | 15 | 46,567 | 57.68 | 15 | 34,168 | 42.32 | - | no ballots | 80,735 | NC | ||||||

| Ohio | 21 | 148,157 | 54.10 | 21 | 124,782 | 45.57 | - | 903 | 0.33 | - | 273,842 | OH | ||||

| Pennsylvania | 30 | 144,010 | 50.00 | 30 | 143,676 | 49.88 | - | 340 | 0.12 | - | 288,026 | PA | ||||

| Rhode Island | 4 | 5,278 | 61.22 | 4 | 3,301 | 38.29 | - | 42 | 0.49 | - | 8,621 | RI | ||||

| South Carolina | 11 | no popular vote | no popular vote | 11 | no popular vote | - | SC | |||||||||

| Tennessee | 15 | 60,194 | 55.66 | 15 | 47,951 | 44.34 | - | no ballots | 108,145 | TN | ||||||

| Vermont | 7 | 32,445 | 63.90 | 7 | 18,009 | 35.47 | - | 319 | 0.63 | - | 50,773 | VT | ||||

| Virginia | 23 | 42,637 | 49.35 | - | 43,757 | 50.65 | 23 | no ballots | 86,394 | VA | ||||||

| TOTALS: | 294 | 1,275,583 | 52.87 | 234 | 1,129,645 | 46.82 | 60 | 7,453 | 0.31 | - | 2,412,694 | US | ||||

| TO WIN: | 148 | |||||||||||||||

Campaign songs/slogans

Harrison

|

Abbreviated version

First verse and chorus. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

Full version

All twelve verses. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Van Buren

- Rockabye, baby, Daddy's a Whig

- When he comes home, hard cider he'll swig

- When he has swug

- He'll fall in a stu

- And down will come Tyler and Tippecanoe.

- Rockabye, baby, when you awake

- You will discover Tip is a fake.

- Far from the battle, war cry and drum

- He sits in his cabin a'drinking bad rum.

- Rockabye, baby, never you cry

- You need not fear of Tip and his Ty.

- What they would ruin, Van Buren will fix.

- Van's a magician, they are but tricks.

Election paraphernalia

Harrison "Tippecanoe Club" ribbon

Harrison "Tippecanoe Club" ribbon Ribbon for Harrison political rally

Ribbon for Harrison political rally Ribbon for Danvers, Mass. delegation to Harrison Rally, Bunker Hill, 1840; engraved by George Girdler Smith

Ribbon for Danvers, Mass. delegation to Harrison Rally, Bunker Hill, 1840; engraved by George Girdler Smith Delegate badge, Democratic convention

Delegate badge, Democratic convention Cover of Boston Harrison Club's Harrison Melodies, 1840[4]

Cover of Boston Harrison Club's Harrison Melodies, 1840[4]

Electoral college selection

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| Each Elector appointed by state legislature | South Carolina |

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide | (all other States) |

In popular culture

In the film Amistad, Van Buren (played by Nigel Hawthorne) is seen campaigning for re-election. These scenes have been criticized for their historical inaccuracy.[5]

See also

- History of the United States (1789-1849)

- Second Party System

- United States House of Representatives elections, 1840

- United States Senate elections, 1840

References

- 1 2 Between 1828-1928: "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections: 1828 - 2008". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- ↑ "About US President William Henry Harrison". What is USA News. 17 September 2013. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ↑ Watson, Harry L. (2006). Liberty and Power: The Politics of Jacksonian America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 226. ISBN 0-8090-6547-9.

- ↑ Boston Harrison Club. Harrison melodies: Original and selected. Boston: Weeks, Jordan and company, 1840. Google books

- ↑ Foner, Eric (March 1998). "The Amistad Case in Fact and Film".

Further reading

- Chambers, William Nisbet. "The Election of 1840" in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. (ed.) History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–1968 (1971) vol 2; analysis plus primary sources

- Formisano, Ronald P. "The new political history and the election of 1840," Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Spring 1993, Vol. 23 Issue 4, pp. 661–82 in JSTOR

- Gunderson, Robert Gray (1957). The Log-Cabin Campaign. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

- Greeley, Horace (1868). Recollections of a Busy Life.

- Greeley's description of the 1840 election is posted on Wikisource.

- Holt, Michael F. "The Election of 1840, Voter Mobilization, and the Emergence of the Second American Party System: A Reappraisal of Jacksonian Voting Behavior," in Holt and John McCardell, eds. A Master's Due: Essays in Honor of David Herbert Donald (1986); emphasizes economic factors; See Formisano (1993) for criticism

- Holt, Michael F. (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505544-6.

- Shade, William G. "Politics and Parties in Jacksonian America," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 110, No. 4 (Oct. 1986), pp. 483–507 online

- Zboray, Ronald J., and Mary Saracino Zboray. "Whig Women, Politics, and Culture in the Campaign of 1840: Three Perspectives from Massachusetts," Journal of the Early Republic Vol. 17, No. 2 (Summer, 1997), pp. 277–315 in JSTOR

External links

- Presidential Election of 1840: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- "The Campaign of 1840: William Henry Harrison and Tyler, Too" high school level lesson plans and documents

- "Overview of Whig National Convention of 1839". Our Campaigns.com. Retrieved 2006. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1840 popular vote by counties

- How close was the 1840 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Election of 1840 in Counting the Votes