1837 Racer's hurricane

Racer's hurricane was a destructive tropical cyclone that had severe effects on northeastern Mexico and the Gulf Coast of the United States in early October 1837. It takes its name from the Royal Navy ship Racer, which sustained some damage when it encountered the hurricane in the northwestern Caribbean Sea. The storm first affected Jamaica with flooding rainfall and strong winds on September 26 and 27, before entering the Gulf of Mexico by October 1. As the hurricane approached northern Tamaulipas and southern Texas, it slowed to a crawl and turned sharply eastward. The storm battered the Gulf Coast from Texas to the Florida Panhandle between October 3 and 7, and after crossing the Southeastern United States, it emerged into the Atlantic shipping lanes off the Carolinas. For most of the storm's duration, the strongest winds and heaviest rains were confined to the northern side of its track.

The effects of the tropical cyclone were far-reaching. Matamoros, on the southern bank of the Rio Grande, faced hurricane conditions for several days, with significant damage to ships. Many towns along the Texas shoreline were inundated by the storm surge, which flooded the coastal plains for miles inland. Galveston Island was devastated, with nearly every building washed away and most vessels driven ashore. To the east, a water level rise of 8 ft (2.4 m) on Lake Pontchartrain submerged low-lying areas of New Orleans, where strong winds unroofed houses. Many buildings along the shores of the lake were swept away, and multiple steamboats were destroyed. The hurricane destroyed the first American lighthouse constructed outside the Thirteen Colonies. Storm surge and wind damage extended into Mississippi and Alabama, but to a lesser degree of severity. In the interior Southeast, sugar cane and cotton crops took heavy losses. As the weakening storm buffeted the Outer Banks of North Carolina on October 9, a passenger steamboat called the SS Home ran aground about 300 ft (91 m) off Cape Hatteras, and rapidly broke up in the pounding surf. Of the 130 passengers and crewmen, about 90 perished. Overall, Racer's hurricane killed an estimated 105 people.

Meteorological history

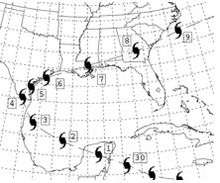

Little is known about the origins of the storm, though modern reanalysis efforts suggest that it was first noted at Barbados on September 22.[1] The intensifying hurricane passed just south of Jamaica on September 26 and 27,[2] affecting the island with strong winds and heavy rains. On September 28, HMS Racer, a Royal Navy sloop-of-war, encountered the storm in the northwestern Caribbean.[3] She was dismasted and blown on her beam ends twice before re-righting,[2] and a young boy plus two crewmen aboard the ship died during the hurricane.[4] Since the ship was apparently the first to observe the cyclone at sea, writers and historians have commonly referred to the system as Racer's storm or Racer's hurricane.[5][3]

As the Racer endured the gale, another vessel to her north, HMS Ringdove, felt the storm around the same time. Both ships recorded easterly winds for several days as they traversed the Yucatán Channel, indicating that the storm center remained to their south.[5] The hurricane crossed the northern Yucatán Peninsula and moved west-northwestward across the Gulf of Mexico, nearing the mouth of the Rio Grande by early on October 3.[3] The storm is estimated to have peaked as the equivalence of a Category 4 or stronger on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale.[6] As the hurricane approached a strong high pressure area to the north, it slowed drastically and recurved sharply to the northeast while its center was just off southern Texas.[7][8]

The slow-moving hurricane battered the Texas shoreline for several days from October 3 through 5,[9] and continued eastward parallel to the Gulf Coast. It passed the Sabine River on the night of October 5–6,[10] and later struck southeastern Louisiana near Venice.[11] At New Orleans, the worst of the storm came late on October 6 with winds from the south and southeast.[12] Extensive damage to forests in interior Louisiana and Mississippi indicated that the strongest winds occurred away from the coast, on the northern side of the hurricane's circulation. This was likely the result of a tight pressure gradient between the storm and the expansive high pressure area centered over the Ohio Valley. According to weather historian David Ludlum, the storm likely moved ashore between Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida.[13] Although the cyclone's path across the southern United States is uncertain, it was located along the coast of the Carolinas as a minimal hurricane by October 8,[8][12] and subsequently exited into the Atlantic. It continued northeastward, ultimately passing north of Bermuda as it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[14]

Impact

Racer's storm was described by David Ludlum as "one of the most famous and destructive hurricanes of the century." It killed an estimated 105 people along its course.[15]

In Jamaica, heavy rainfall triggered widespread street flooding, forcing nearly all businesses in Kingston to close for the duration of the storm. Along the coast, several ships broke from their moorings; one of them struck a wharf, damaging another vessel, and was scuttled to prevent further destruction.[16]

Matamoros, Tamaulipas, on the southern bank of the Rio Grande, experienced the hurricane for several days beginning on October 2.[10] Along the coast, several ships were wrecked.[17] The Mexican custom house, situated at the mouth of the river, was destroyed. It was later rebuilt at a more sheltered location farther inland.[3]

United States

The storm wrought destruction along the entire Texas shoreline, with substantial shipping losses. All ships in the harbors at Brazos Santiago and Velasco were sunk or driven aground.[3][9] Communities along the shores of Matagorda Bay were heavily damaged, as buildings and wharves were swept away.[3] Farther north, a 6 to 7 ft (1.8 to 2.1 m) storm surge flooded Galveston Island, where nearly every building was destroyed, along with all supplies and provisions.[9] Of the 30 vessels present in the harbor at Galveston when the storm began, only one remained moored following its passage.[18] Some ships were pushed several miles inland; in one case, a brig was driven against a three-story warehouse, causing it to collapse.[9][18] Among the ships destroyed at Galveston were two Texas Navy schooners. In a scene of "utter desolation", individuals in Galveston survived the flooding by grasping to floating debris for days.[18] Floodwaters surged inland for many miles over the coastal prairies, drowning livestock.[19] At Houston, the surf action, accompanied by a 4 ft (1.2 m) surge, altered the coastline. Near Sabine Pass, the storm washed a three-masted barque 7 mi (11 km) inland, where residents would salvage its timbers for firewood and home building materials for decades to come.[9] Despite the damage throughout coastal Texas, only two people are known to have died, including one in Galveston.[18]

In New Orleans, the storm produced an 8 ft (2.4 m) storm surge on Lake Pontchartrain that flooded parts of the city as far south as Burgundy Street, with water 2 ft (0.6 m) deep invading many homes.[13] Strong winds in the city toppled chimneys, brought down trees and fences, and unroofed homes, carrying some roofs up to 100 ft (30 m) away from the damaged buildings. In particular, the City Exchange hotel (where the Omni Royal Orleans now sits) was extensively damaged while in the final stages of its construction.[20][21] In the settlement known then as Port Pontchartrain, a pier and breakwater sustained a combined $50,000 (1837 USD) in damage, and most buildings there were swept away. At least one person was killed in the area, and several more went missing while evacuating their homes. Numerous steamboats were wrecked on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, and much of the Pontchartrain Railroad was flooded or washed out, with damage estimated at $100,000.[13] The hurricane also destroyed the original Bayou St. John Light, the first American lighthouse built outside the Thirteen Colonies.[20] In addition to the wind and coastal flooding, torrential rains overspread areas north of the storm's track. In Clinton, Louisiana, heavy precipitation lasted nearly two days.[13] Across Louisiana and Mississippi, the storm killed at least six people.[20]

All of the wharves along the coast of Mississippi were reportedly ruined.[20] In Mobile, Alabama, the storm uprooted trees and damaged several buildings, including a church. Tides rose several feet above normal, flooding low-lying streets such that fishermen were able to deliver their catches directly to market by boat. Some businesses sustained minor water damage, but overall, the city was spared any significant destruction, and received little impact on shipping.[22] To the east, there were unconfirmed reports of significant damage to wharves and warehouses along the Florida Panhandle, but these accounts may have been exaggerated by rival companies.[13]

Throughout the Southeast, the storm caused heavy agricultural damage,[13] with up to a third of the sugar cane and cotton crops destroyed in the hardest-hit plantations.[23] Reports of strong winds extended as far inland as eastern Tennessee.[13] At Norfolk, Virginia, northeasterly gales on October 8 and 9 kept steamboats at dock.[8] Several ships, including the Enterprise and the Cumberland, were lost along the Outer Banks.[24] One sailor fell overboard and drowned when a schooner ran aground at Swansboro, North Carolina.[25]

SS Home

The newly built passenger steamboat SS Home was en route from New York City to Charleston, South Carolina, when she encountered strengthening northeasterly winds on October 8.[24][26] As the storm worsened that night, the 220 ft (67 m) craft began to leak due to a broken boiler feed pipe.[27][28] The next morning, as the Home took on more water than the pumps could handle, the captain steered her aground 22 mi (35 km) north of Cape Hatteras. The vessel got underway again shortly thereafter, in an effort to reach the relative shelter of the cape's leeward side and beach her there.[26]

All passengers and crewmen were ordered to assist in bailing out the water pouring into the hold, but despite their best efforts, the engine rooms were inundated and the Home was forced to continue under sail. On the night of October 9–10, the vessel grounded out 300 ft (90 m) from the shore,[27] just south of Cape Hatteras.[26] The largely submerged Home rapidly broke up amid the hurricane's pounding surf, and of the 130 people aboard the steamboat, only about 40 made it to shore alive: 20 out of 90 passengers and 20 crew members, including the captain.[27] A lifeboat carrying between 10 and 15 passengers capsized shortly after being launched, leading to their deaths,[29] and the two other lifeboats were destroyed before they could be used.[30] Two men used the only two life preservers aboard the Home to safely reach the beach.[29] Following the disaster, Congress passed a law requiring commercial vessels to carry enough life preservers for all passengers.[31]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Chenoweth, Michael (May 2006). "A Reassessment of Historical Atlantic Basin Tropical Cyclone Activity, 1700–1855" (PDF). Climate Change. National Hurricane Center. 76 (1): p. 63. doi:10.1007/s10584-005-9005-2. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- 1 2 Geiser, p. 60

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ludlum, p. 145

- ↑ Reid, p. 136

- 1 2 Reid, p. 133

- ↑ Elsner, James. "Storm 9 – 1837 – Possible Track" (PDF). Florida State University. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Redfield, p. 34

- 1 2 3 Elsner, James. "1837 – No. 2 – Racer's Storm – Oct. 1–6 – Pt. 2" (PDF). Florida State University. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roth, David (January 17, 2010). "Texas Hurricane History" (PDF). National Weather Service. p. 14. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- 1 2 Geiser, p. 61

- ↑ Roth, David (July 16, 2001). "Virginia Hurricane History: Early Nineteenth Century". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- 1 2 Redfield, p. 33

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ludlum, p. 146

- ↑ Reid, p. 143

- ↑ National Hurricane Center (January 20, 2016). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ↑ Reid, p. 141

- ↑ "Maritime Disasters". Boston Post. November 6, 1837. p. 2. Retrieved January 21, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 Ludlum, pp. 145–146

- ↑ "Texas". Democratic Free Press. November 15, 1837. p. 2. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Roth, David (April 8, 2010). "Louisiana Hurricane History" (PDF). National Weather Service Camp Springs, Maryland. pp. 15–16. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Effects of the storm". The Baltimore Sun. October 16, 1837. p. 2. Retrieved January 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Another Gale". The Baltimore Sun. October 16, 1837. p. 2. Retrieved January 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Latest from New Orlans (sic)". Maumee City Express. November 18, 1837. p. 2. Retrieved January 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Hudgins, James E. (October 2007). "Tropical Cyclones Affecting North Carolina Since 1856 – An Historical Perspective" (PDF). National Weather Service Blacksburg, Virginia. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ↑ "None". Newbern Spectator. October 27, 1837. p. 3. Retrieved January 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Ludlum, p. 147

- 1 2 3 Fraser, p. 110

- ↑ Howland, p. 18

- 1 2 Fraser, p. 111

- ↑ Howland, p. 29

- ↑ Fraser, p. 112

Sources

- Fraser, Walter J., Jr. (2009). Lowcountry Hurricanes. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-2866-9.

- Geiser, Samuel W. (1944). "Racer's storm (1837) with notes on other Texas hurricanes in the period 1818-1886" (PDF). Field & Laboratory. Southern Methodist University Press. 12 (2): pp. 59–67.

- Howland, Southworth Allen (1840). Steamboat disasters and railroad accidents in the United States : to which is appended accounts of recent shipwrecks, fires at sea, thrilling incidents, etc. Dorr, Howland & Co.

- Ludlum, David M. (1963). Early American hurricanes, 1492–1870. American Meteorological Society. ISBN 0-933876-16-5.

- Redfield, William C. (1846). On Three Several Hurricanes of the Atlantic, and Their Relations to the Northers of Mexico and Central America: With Notices of Other Storms. B.L. Hamlen.

- Reid, William (1850). An attempt to develop the law of storms by means of facts: arranged according to place and time; and hence to point out a cause for the variable winds, with the view to practical use in navigation (3rd ed.). John Weale.