United States presidential election, 1800

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

138 electoral votes of the Electoral College 70 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

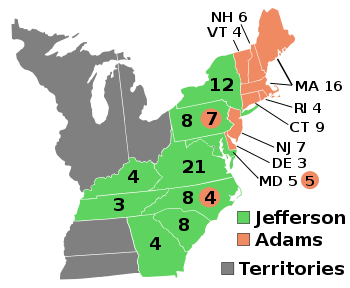

Presidential election results map. Green denotes states won by Jefferson, burnt orange denotes states won by Adams, and gray denotes non voting territories. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1800 was the fourth quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Friday, October 31 to Wednesday, December 3, 1800. In what is sometimes referred to as the "Revolution of 1800",[1][2] Vice President Thomas Jefferson defeated President John Adams. The election was a realigning election that ushered in a generation of Democratic-Republican Party rule and the eventual demise of the Federalist Party in the First Party System. It was a long, bitter re-match of the 1796 election between the pro-French and pro-decentralization Democratic-Republicans under Jefferson and Aaron Burr and the incumbent Adams and Charles Pinckney's pro-British and pro-centralization Federalists. The chief political issues revolved around the fallout from the French Revolution, including opposition to the tax imposed by Congress to pay for the mobilization of the new army and the navy in the Quasi-War against France in 1798. The Alien and Sedition Acts, by which Federalists were trying to stifle dissent from Democratic-Republican newspaper editors, also proved to be highly controversial.

While the Democratic-Republicans were well organized at the state and local levels, the Federalists were disorganized and suffered a bitter split between their two major leaders, President Adams and Alexander Hamilton. The jockeying for electoral votes, regional divisions, and the propaganda smear campaigns created by both parties made the election recognizably modern.[3]

The election exposed one of the flaws in the original Constitution of the United States. Members of the Electoral College were authorized by the original Constitution to vote for two names for President. (The two-vote ballot was created in order to try to maximize the possibility that one candidate received votes from a majority of the electors nationwide; the drafters of the Constitution had not anticipated the rise of organized political parties, which made it much easier to attain a nationwide majority.) The candidate with the most electoral votes would become President and the candidate with the second most would become Vice President. The Democratic-Republicans had planned for one of the electors to abstain from casting his second vote for Aaron Burr, which would have led to Jefferson receiving one electoral vote more than Burr, making Jefferson President and Burr Vice President. The plan, however, was mishandled. Each elector who voted for Jefferson also voted for Burr, resulting in a tied electoral vote. The election was then put into the hands of the outgoing House of Representatives, which, after 35 votes in which neither Jefferson nor Burr obtained a majority, elected Jefferson on the 36th ballot.

To rectify the flaw in the original presidential election mechanism, the Twelfth Amendment, ratified in 1804, was added to the United States Constitution. It called for electors to make a distinct choice between their selections for president and vice president.

The result of this election was affected by the three-fifths clause of the United States Constitution, by which slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of Congressional apportionment. Historians such as Garry Wills, Leonard L. Richards, and William W. Freehling have written that had slaves not been counted at all, Adams would have won the electoral vote.[4] Adams had never owned a slave and was opposed to slavery, while Jefferson was an avowed slave owner. Jefferson was subsequently criticized as having won "the temple of Liberty on the shoulders of slaves".[5] Akhil Reed Amar, a law and political science professor at Yale, argued that the election was a turning point in American history and claimed that "in a direct election system, the South would have lost every time."[6]

General election

Candidates

Democratic-Republican nomination

- Thomas Jefferson, Vice President of the United States from Virginia

- Aaron Burr, former U.S. Senator from New York

Federalist nomination

- John Adams, President of the United States from Massachusetts

- Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, former U.S. Minister to France from South Carolina

Campaign

The 1800 election was a re-match of the 1796 election. The campaign was bitter and characterized by slander and personal attacks on both sides. Federalists spread rumors that the Democratic-Republicans were radicals who would ruin the country (based on the Democratic-Republican support for the French Revolution). In 1798, George Washington had complained "that you could as soon scrub the blackamoor white, as to change the principles of a professed Democrat; and that he will leave nothing unattempted to overturn the Government of this Country".[7] Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republicans accused Federalists of subverting republican principles with the Alien and Sedition Acts, some of which were later declared unconstitutional after their expiration by the Supreme Court, and relying for their support on foreign immigrants; they also accused Federalists of favoring Britain and the other coalition countries in their war with France in order to promote aristocratic, anti-democratic values.[8]

Adams was attacked by both the opposition Democratic-Republicans and a group of so-called "High Federalists" aligned with Alexander Hamilton. The Democratic-Republicans felt that the Adams foreign policy was too favorable toward Britain; feared that the new army called up for the Quasi-War would oppress the people; opposed new taxes to pay for war; and attacked the Alien and Sedition Acts as violations of states' rights and the Constitution. "High Federalists" considered Adams too moderate and would have preferred the leadership of Alexander Hamilton instead.

Hamilton had apparently grown impatient with Adams and wanted a new president who was more receptive to his goals. During Washington's presidency, Hamilton had been able to influence the federal response to the Whiskey Rebellion (which threatened the government's power to tax citizens). When Washington announced that he would not seek a third term, Adams was widely recognized by the Federalists as next-in-line.

Hamilton appears to have hoped in 1796 that his influence within an Adams administration would be as great or greater than in Washington's. By 1800, Hamilton had come to realize that Adams was too independent and thought the Federalist vice presidential candidate, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina, more suited to serving Hamilton's interests. In his third sabotage attempt toward Adams,[9] Hamilton quietly schemed to elect Pinckney to the presidency. Given Pinckney's lack of political experience, he would have been expected to be open to Hamilton's influence. However, Hamilton's plan backfired and hurt the Federalist party, particularly after one of his letters, a scathing criticism of Adams that was fifty-four pages long,[10] fell into the hands of a Democratic-Republican and soon after became public. It embarrassed Adams and damaged Hamilton's efforts on behalf of Pinckney,[3] not to mention speeding Hamilton's own political decline.[10]

Selection method changes

Partisans on both sides sought any advantage they could find. In several states, this included changing the process of selecting electors to ensure the desired result. In Georgia, Democratic-Republican legislators replaced the popular vote with selection by the state legislature. Federalist legislators did the same in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. This may have had some unintended consequences in Massachusetts, where the makeup of the delegation to the House of Representatives changed from 12 Federalists and 2 Democratic-Republicans to 8 Federalists and 6 Democratic-Republicans, perhaps the result of backlash on the part of the electorate. Pennsylvania also switched to legislative choice, but this resulted in an almost evenly split set of electors. Virginia switched from electoral districts to winner-take-all, a move that probably switched one or two votes out of the Federalist column.

Voting

Because each state could choose its own election day in 1800, voting lasted from April to October. In April, Burr's successful mobilization of the vote in New York City succeeded in reversing the Federalist majority in the state legislature to provide decisive support for the Democratic-Republican ticket. With the two parties tied 63–63 in the Electoral College in the autumn of 1800, the last state to vote, South Carolina, chose eight Democratic-Republicans to award the election to Jefferson and Burr.

Under the United States Constitution as it then stood, each elector cast two votes, and the candidate with a majority of the votes was elected president, with the vice presidency going to the runner-up. The Federalists therefore arranged for one of their electors to vote for John Jay rather than for Pinckney. The Democratic-Republicans had a similar plan to have one of their electors cast a vote for another candidate instead of Burr, but failed to execute it, thus all of the Democratic-Republican electors cast their votes for both Jefferson and Burr, 73 in all for each of them. According to a provision of the United States Constitution, a tie in a case of this type had to be resolved by the House of Representatives, with each state casting one vote. Although the congressional election of 1800 turned over majority control of the House of Representatives to the Democratic-Republicans by 65 seats to 35,[11] the presidential election had to be decided by the outgoing House that had been elected in the congressional election of 1798 (at that time, the new presidential and congressional terms all started on March 4 of the year after a national election). In the outgoing House, the Federalists retained a majority of 90 seats to 54.[11][3]

Disputes

Defective certificates

When the electoral ballots were opened and counted on February 11, 1801, it turned out that the certificate of election from Georgia was defective. While it was clear that the electors had cast their votes for Jefferson and Burr, the certificate did not take the constitutionally mandated form of a "List of all the Persons voted for, and of the Number of Votes for each".[12] Vice President Jefferson, who was counting the votes in his role as President of the Senate, immediately counted the votes from Georgia as votes for Jefferson and Burr.[12] No objections were raised.[12] If the disputed Georgia ballots were rejected on these technicalities, Jefferson and Burr would have lost 4 electoral votes, leaving them with 69 electoral votes each. The counting of the votes would have failed to result in a majority of 70 votes for any of the four candidates, causing a constitutionally mandated Congressional runoff among the top five finishers. Instead, the total number of votes for Jefferson and Burr was 73, a majority of the total, but a tie between them.[12]

Results

Of the 155 counties and independent cities making returns, Jefferson won in 115 (74.19%), whereas Adams carried 40 (25.81%). This was the first time that New York voted for the Democratic-Republicans. This was also the last time that Vermont voted for the Federalists.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a), (b), (c) | Electoral vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| Thomas Jefferson | Democratic-Republican | Virginia | 41,330 | 61.4% | 73 |

| Aaron Burr | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 73 |

| John Adams (incumbent) | Federalist | Massachusetts | 25,952 | 38.6% | 65 |

| Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 64 |

| John Jay | Federalist | New York | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 67,282 | 100.0% | 276 | ||

| Needed to win | 70 | ||||

Source (Popular Vote): U.S. President National Vote. Our Campaigns. (February 10, 2006).

Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825[13]

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

(a) Votes for Federalist electors have been assigned to John Adams and votes for Democratic-Republican electors have been assigned to Thomas Jefferson.

(b) Only 6 of the 16 states chose electors by any form of popular vote.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

Breakdown by ticket

| Presidential candidate | Running mate | Electoral vote |

|---|---|---|

| Thomas Jefferson | Aaron Burr | 73 |

| John Adams | Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | 64 |

| John Adams | John Jay | 1 |

House election of 1801

The members of the House of Representatives balloted as states to determine whether Jefferson or Burr would become president. There were sixteen states, each with one vote; an absolute majority of nine was required for victory. It was the outgoing House of Representatives, controlled by the Federalist Party, that was charged with electing the new president. While everyone knew that Republicans intended Jefferson to be their candidate for president and Burr for vice president, that did not bind the Federalists. Many were unwilling to support Jefferson, their principal political enemy since 1791. Seizing an opportunity to deny Jefferson the presidency, most Federalists voted for Burr, giving Burr six of the eight states controlled by Federalists. The seven delegations controlled by Republicans all voted for Jefferson, and Georgia's sole Federalist representative also voted for him, giving him eight states. The Vermont delegation was evenly split and cast a blank ballot. The remaining state, Maryland, had five Federalist representatives to three Republicans; one of its Federalist representatives voted for Jefferson, forcing that state delegation also to cast a blank ballot.[14]

Over the course of seven days, from February 11 to 17, the House cast a total of 35 ballots, with Jefferson receiving the votes of eight state delegations each time—one short of the necessary majority of nine. During the contest, Hamilton recommended to Federalists that they support Jefferson because he was "by far not so dangerous a man" as Burr; in short, he would much rather have someone with wrong principles than someone devoid of any.[10] Hamilton embarked on a frenzied letter-writing campaign to get delegates to switch votes.[15]

On February 17, on the 36th ballot, Jefferson was elected. Federalist James A. Bayard of Delaware and his allies in Maryland and Vermont all cast blank ballots.[16] This resulted in the Maryland and Vermont votes changing from no selection to Jefferson, giving him the votes of 10 states and the presidency. Bayard, as the sole representative from Delaware, changed his vote from Burr to no selection.[3] The four representatives present from South Carolina, all Federalists, also changed their 3–1 selection of Burr to four abstentions.

Results

| State delegation | Ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd–35th(a) | 36th | |

| Overall results | 8 Jefferson 6 Burr 2 No result |

10 Jefferson 4 Burr 2 No result | |

| Georgia(b) | Jefferson (1–0) | Jefferson (1–0) | Jefferson (1–0) |

| Kentucky | Jefferson (2–0) | Jefferson (2–0) | Jefferson (2–0) |

| New Jersey | Jefferson (3–2) | Jefferson (3–2) | Jefferson (3–2) |

| New York | Jefferson (6–4) | Jefferson (6–4) | Jefferson (6–4) |

| North Carolina | Jefferson (9–1) | Jefferson (6–4) | Jefferson (6–4) |

| Pennsylvania | Jefferson (9–4) | Jefferson (9–4) | Jefferson (9–4) |

| Tennessee | Jefferson (1–0) | Jefferson (1–0) | Jefferson (1–0) |

| Virginia | Jefferson (16–3) | Jefferson (14–5) | Jefferson (14–5) |

| Maryland | no result (4–4) | no result (4–4) | Jefferson (4–0–4) |

| Vermont | no result (1–1) | no result (1–1) | Jefferson (1–0–1) |

| Delaware | Burr (0–1) | Burr (0–1) | no result (0–0–1) |

| South Carolina(c) | Burr (0–4) | Burr (1–3) | no result (0–0–4) |

| Connecticut | Burr (0–7) | Burr (0–7) | Burr (0–7) |

| Massachusetts | Burr (3–11) | Burr (3–11) | Burr (3–11) |

| New Hampshire | Burr (0–4) | Burr (0–4) | Burr (0–4) |

| Rhode Island | Burr (0–2) | Burr (0–2) | Burr (0–2) |

(a) The votes of the representatives is typical and may have fluctuated from ballot to ballot, but the result for each state did not change.

(b) Even though Georgia had two representatives apportioned, one seat was vacant due to the death of James Jones.

(c) Even though South Carolina had six representatives apportioned, Thomas Sumter was absent due to illness, and Abraham Nott departed for South Carolina between the first and final ballots.

Electoral college selection

The Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, provided that the state legislatures should decide the manner in which their electors were chosen. Different state legislatures chose different methods:[17]

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| State is divided into electoral districts, with one Elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | Kentucky Maryland North Carolina |

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide | Rhode Island Virginia |

|

Tennessee |

| Each Elector appointed by state legislature | (all other states) |

In popular culture

The election of 1800 was the topic of the song 'The Election of 1800' from the Broadway musical Hamilton.[18] The election's story and the eventual reconciliation between Jefferson and Adams was also retold in a second season episode of Comedy Central's Drunk History, with Jerry O'Connell portraying Jefferson and Joe Lo Truglio as Adams.

See also

- First inauguration of Thomas Jefferson

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

- Stephen Simpson (writer) (editor of the Aurora, a Philadelphia newspaper Jefferson credited for his victory in 1800)

References

Primary references

- Annals of the Congress of the United States, Washington, D.C.: Gales and Seaton, 1834–1856, pp. 10:1028–1033

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved March 20, 2005.

Inline references

- ↑ "Thomas Jefferson: The Revolution of 1800". PBS. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ↑ "A Revolution of 1800 After All: The Political Culture of the Earlier Early Republic and the Origins of American Democracy". Jeffrey L. Pasley University of Missouri-Columbia. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Ferling (2004)

- ↑ Negro President: Jefferson and the Slave Power; Garry Wills; Houghton Mifflin: pp. 2, 234.

- ↑ "Thomas Jefferson, the 'Negro President' Chronicle of Founding Father's Three-Fifths Slave Vote Victory". NPR. February 16, 2004. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "The real reason we have an Electoral College: to protect slave states".

- ↑ Mintz, S. (2003). "Gilder Lehrman Document Number: GLC 581". Digital History. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ↑ Buel (1972)

- ↑ McCullough (2001)

- 1 2 3 Chernow (2004)

- 1 2 "Party Divisions of the House of Representatives* 1789–Present". Office of the Historian, House of United States House of Representatives. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Bruce Ackerman and David Fontana, "How Jefferson Counted Himself In," The Atlantic, March 2004. See also: Bruce Ackerman and David Fontana, "Thomas Jefferson Counts Himself into the Presidency," (2004), 90 Virginia Law Review 551-643.

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes".

- ↑ John Ferling, Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800 (2004) pp 175-96.

- ↑ Roberts (2008)

- ↑ Noel Campbell and Marcus Witcher, "Political entrepreneurship: Jefferson, Bayard, and the election of 1800." Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy 4.3 (2015): 298-312.

- ↑ "The Electoral Count for the Presidential Election of 1789". The Papers of George Washington. Retrieved May 4, 2005.

- ↑ Prokop, Andrew (November 28, 2015). "The real-life election of 1800 was even wilder than Hamilton the musical lets on". Vox. Vox Media, Inc.http://www.vox.com/2015/11/28/9801376/hamilton-election-of-1800-burr-jefferson

Bibliography

- Ben-Atar, Doron; Oberg, Barbara B., eds. (1999), Federalists Reconsidered, University of Virginia Press, ISBN 978-0-8139-1863-1

- Pasley, Jeffrey L.; et al., eds. (2004), Beyond the Founders: New Approaches to the Political History of the Early American Republic, University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 978-0-8078-5558-4

- Beard, Charles A. (1915), The Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy, ISBN 978-1-146-80267-3

- Bowling, Kenneth R.; Kennon, Donald R. (2005), Establishing Congress: The Removal to Washington, D.C., and the Election of 1800, Ohio University Press, ISBN 978-0-8214-1619-8

- Buel, Richard (1972), Securing the Revolution: Ideology in American Politics, 1789–1815

- Chambers, William Nisbet (1963), Political Parties in a New Nation: The American Experience, 1776–1809

- Chernow, Ron (2005), Alexander Hamilton, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-303475-9

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr. (1965), The Making of the American Party System 1789 to 1809

- Dunn, Susan (2004), Jefferson's second revolution: The Election Crisis of 1800 and the Triumph of Republicanism, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-618-13164-8

- Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1995), The Age of Federalism

- Ferling, John (2004), Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800

- Fischer, David Hackett (1965), The Revolution of American Conservatism: The Federalist Party in the Era of Jeffersonian Democracy

- Freeman, Joanne B. (2001), Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic

- Freeman, Joanne B. (1999), "The election of 1800: a study in the logic of political change", Yale Law Journal, 108 (8): 1959–1994, JSTOR 797378, doi:10.2307/797378

- Goodman, Paul (1967), "The First American Party System", in Chambers, William Nisbet; Burnham, Walter Dean, The American Party Systems: Stages of Political Development, pp. 56–89

- Hofstadter, Richard (1970), The Idea of a Party System

- Kennedy, Roger G. (2000), Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character, Oxford University Press

- McCullough, David (2001), John Adams

- Horn, James P. P.; Lewis, Jan Ellen; Onuf, Peter S. (2002), The Revolution of 1800: Democracy, Race, and the New Republic

- Miller, John C. (1959), Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox

- Roberts, Cokie (2008), Ladies of Liberty

- Schachner, Nathan (1961), Aaron Burr: A Biography

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier, ed. (1986), History of American Presidential Elections, 1789-1984, Vol. 1, essay and primary sources on 1800.

- Sharp, James Roger. The Deadlocked Election of 1800: Jefferson, Burr, and the Union in the Balance (University Press of Kansas; 2010) 239 pages;

- Wills, Garry (2003), "Negro President": Jefferson and the Slave Power, Houghton Mifflin Co., pp. 47–89, ISBN 0-618-34398-9 . . . also listed (in at least one source) as from Mariner Books (Boston) in 2004

External links

- Presidential Election of 1800: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Documentary Timeline 1787-1800 Lesson plans from NEH

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825

- Vote Archive: Town Map of Election Results in Rhode Island

- Vote Archive: County Map of Election Results in Virginia

- Overview at Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

- Booknotes interview with Bernard Weisberger on America Afire: Jefferson, Adams, and the First Contested Election, February 25, 2001.

- Booknotes interview with John Ferling on Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, October 3, 2004.

- Election of 1800 in Counting the Votes

%2C_2nd_president_of_the_United_States%2C_by_Asher_B._Durand_(1767-1845)-crop.jpg)