Scilly naval disaster of 1707

.jpg) An 18th-century engraving of the disaster, with HMS Association in the centre | |

| Occurrence summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | 22 October 1707 |

| Summary | Navigation accident |

| Site |

Isles of Scilly, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom 49°51′56″N 6°23′50″W / 49.86556°N 6.39722°WCoordinates: 49°51′56″N 6°23′50″W / 49.86556°N 6.39722°W |

| Fatalities | 1,550 |

| Injuries (non-fatal) | 13 |

| Survivors | 13 |

| Operator | Royal Navy |

| Destination | Portsmouth, England |

The Scilly naval disaster of 1707 was the loss of four warships of a Royal Navy fleet off the Isles of Scilly in severe weather on 22 October 1707. 1550 sailors lost their lives aboard the wrecked vessels, making the incident one of the worst maritime disasters in British naval history [1]. The disaster has been attributed to the navigators' inability to accurately calculate their positions, to errors in the available charts and pilot books, to inadequate compasses, or to a combination of these factors [2].

Background

In the summer of 1707, during the War of the Spanish Succession, a combined British, Austrian and Dutch force under the command of Prince Eugene of Savoy besieged and attempted to take the French port of Toulon. During this campaign, which was fought from 29 July to 21 August, Great Britain dispatched a fleet to provide naval support. Led by the Commander-in-Chief of the British Fleets, Sir Cloudesley Shovell, the ships sailed to the Mediterranean, attacked Toulon and also managed to inflict damage on the French fleet caught in the siege. The overall campaign was nevertheless unsuccessful and the alliance was ultimately defeated by Franco-Spanish units. The British fleet was ordered to return home, and set sail from Gibraltar to Portsmouth in late September. The force under Shovell's command comprised fifteen ships of the line (Association, Royal Anne, Torbay, St George, Cruizer, Eagle, Lenox, Monmouth, Orford, Panther, Romney, Rye, Somerset, Swiftsure, Valeur) as well as four fireships (Firebrand, Griffin, Phoenix, Vulcan), the sloop Weazel and the yacht Isabella [3] [4].

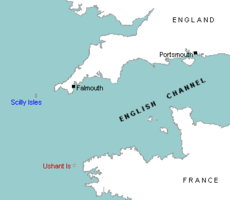

Loss of the ships

Shovell's fleet of twenty-one ships left Gibraltar on 29 September, with HMS Association serving as his own flagship, HMS Royal Anne as flagship of Vice-Admiral of the Blue Sir George Byng and HMS Torbay as flagship of Rear-Admiral of the Blue Sir John Norris.[4] The passage was marked by extremely bad weather and constant squalls and gales. As the fleet sailed out on the Atlantic, passing the Bay of Biscay on their way to England, the weather worsened and storms gradually pushed the ships off their planned course. Finally, on the night of 22 October 1707 Old Style, (2 November 1707 by the modern calendar), the squadron entered the mouth of the English Channel and Shovell's sailing masters believed that they were on the last leg of their journey.[5] The fleet was thought to be sailing safely west of Ushant, an island outpost off the coast of Brittany.[6] However, because of a combination of the bad weather and the mariners' inability to accurately calculate their longitude, the fleet was off course and closing in on the Isles of Scilly instead.[7] Before their mistake could be corrected, the fleet struck rocks and four ships were lost:

- HMS Association, a 90-gun second-rate ship of the line commanded by Captain Edmund Loades, struck the Outer Gilstone Rock (see image)[8] off Scilly's Western Rocks at 8 p.m. and sank, drowning her entire crew of about 800 men and Admiral Shovell himself.[9][10] Following behind the Association was St George,[11] whose crew saw the flagship go down in three or four minutes. St George also struck rocks and suffered damage but eventually managed to get off, as did HMS Phoenix which ran ashore between Tresco and St Martin's[11] but could be kept seaworthy.

- HMS Eagle, a 70-gun third-rate ship of the line commanded by Captain Robert Hancock,[4] hit the Crim Rocks and was lost with all hands on Tearing Ledge amongst the Western Rocks. It is estimated that the HMS Eagle had at least as many crew as the HMS Association;[4] there were no survivors. Sinking a few hundred metres away from Bishop Rock, her wreck lies in a depth of 130 feet.[11]

- HMS Romney, a 50-gun fourth-rate ship of the line commanded by Captain William Coney,[4] hit Bishop Rock and went down with all save one of her 290 crew being lost.[12] The sole survivor from the three largest ships was George Lawrence, who had worked as a butcher before joining the crew of Romney as quartermaster.[13][14]

- HMS Firebrand, a fireship commanded by Captain Francis Percy, struck the Outer Gilstone Rock like Association, but unlike the flagship she was lifted off by a wave. Percy managed to steer his badly damaged ship along the southern side of the Western Rocks[11] between St Agnes and Annet, but she foundered in Smith Sound, sinking close to Menglow Rock and losing 28 of her crew of 40.[13] (It is also reported the survivors numbered 23).[4]

Of other ships in the fleet:[4]

- HMS Royal Ann was saved from foundering by her crew quickly setting her topsails, and weathering the rocks when within a ship's length of them.[4]

The exact number of officers, sailors and marines who were killed in the sinking of the four ships is unknown. Statements vary between 1,400 and over 2,000,[11] making it one of the greatest maritime disasters in British history. For days afterwards, bodies continued to wash onto the shores of the isles along with the wreckage of the warships[15] and personal effects. Many dead sailors from the wrecks were buried on the island of St Agnes.[16] Admiral Shovell's body, along with those of his two Narborough stepsons and his flag-captain, Edmund Loades, washed up on Porthellick Cove on St Mary's the following day, almost seven miles (11 km) from where the Association was wrecked. A small memorial was later erected at this site. The circumstances under which the admiral's remains were found gave rise to stories (see below). Shovell was temporarily buried on the beach on St Mary's (see image).[17] By order of Queen Anne his body was later exhumed, embalmed and taken to London where he was interred in Westminster Abbey.[11] His large marble monument in the south choir aisle was sculpted by Grinling Gibbons.[10] There is a memorial depicting the sinking of the Association in the church at the Narboroughs' home of Knowlton near Dover.

Legends of the disaster

One myth associated with the disaster alleges that a common sailor on the flagship tried to warn Shovell that the fleet was off course but the Admiral had him hanged at the yardarm for inciting mutiny. The story first appeared in the Scilly Isles in 1780, with the common sailor being a Scilly native who recognised the waters as being close to home but was punished for warning the Admiral. It was claimed that grass will never grow on the grave where Shovell was first buried at Porthellick Cove because of his tyrannical act against an islander. The myth was embellished in the 19th century when the punishment became instant execution and the sailor's knowledge of the fleet's position was attributed to superior navigational skills instead of local knowledge. While it is possible that a sailor may have debated the vessel's location and feared for its fate, such debates were common upon entering the English Channel, as noted by Samuel Pepys in 1684. Naval historians have repeatedly discredited the story, noting the lack of any evidence in contemporary documents, its fanciful stock conventions and dubious origins.[4][18][19] However, the myth was revived in 1997 when author Dava Sobel presented it as an unqualified truth in her book Longitude.[6]:11-16

Another story that is often told is that Shovell was alive, at least barely, when he reached the shore of Scilly at Porthellick Cove, but was murdered by a woman for the sake of his priceless emerald ring, which had been given to him by a close friend, Captain James Lord Dursley. At that time, the Scillies had a wild and lawless reputation.[14] According to a letter written in 1709 by Edmund Herbert, who was sent to Scilly by Shovell's family to help locate and recover items belonging to the admiral, Sir Cloudesley's body was first found by two women "stript of his shirt" and "his ring was also lost off his hand, which however left ye impression on his finger." Shovell's widow, Elizabeth, had offered a large reward for the recovery of any family property.[14] It is claimed that the murder only came to light some thirty years later when the woman, on her deathbed, produced the stolen ring and confessed to a clergyman that she had killed the admiral.[6] The clergyman supposedly sent it back to the 3rd Earl of Berkeley,[20] although several historians doubt the murder legend as there is no record of the ring's return and the story stems from a romantic and unverifiable "deathbed confession".[18][19]

Longitude

The disastrous wrecking of a Royal Navy fleet in home waters brought great consternation to the nation. The main cause of the catastrophe has often been portrayed as the navigators' inability to accurately calculate their longitude.[6] Clearly, something better than dead reckoning was needed to find a way through dangerous waters. As transoceanic travel grew in significance, so did the importance of reliable navigation. This eventually led to the Longitude Act in 1714, which established the Board of Longitude and offered large financial rewards for anyone who could find a method of determining longitude accurately at sea.[6] After many years, the consequence of the Act was that accurate marine chronometers were produced and the lunar distance method was developed, both of which became used throughout the world for navigation at sea.

However, it is not certain that the navigational error leading to the wrecking of Admiral Shovell's fleet was purely one of longitude, and no contemporary discussions are known that appear to have related the disaster to either navigation or longitude.[21] The Royal Navy conducted a court-martial of the officers of the Firebrand, who were acquitted, but no officers survived from the other lost ships, so no other courts-martial took place. The Navy also conducted a survey of compasses from the surviving ships and of those at Chatham and Portsmouth dockyards, following comments from Sir William Jumper, captain of the Lenox, that errors in the compasses had caused the navigational error. This showed what a poor state many were in; at Portsmouth, for example, only four of the 112 wooden cased compasses from nine of the returning vessels were found to be serviceable.[22][23]

Some have argued that the disaster was in fact caused more by an error in latitude than in longitude. According to contemporary reports, Shovell initially attempted to determine the fleet's position by astronomical observations and depth soundings before also consulting the sailing masters of his other ships. Shovell's navigation officers believed that the fleet was at a position west of Ushant (48°27′29″N 5°05′44″W / 48.45806°N 5.09556°W), except the sailing master of HMS Lenox who judged that they were nearer to the Isles of Scilly (49°56′10″N 6°19′22″W / 49.93611°N 6.32278°W).[5]

William May points out that the position of the Isles of Scilly themselves was not known accurately in either longitude or latitude. In addition, his analysis of the 40 extant logbooks from the 21 ships in the fleet do not show the error in longitude to be a significant factor compared to latitude.[24]

Discovery of the wrecks

The ships of Sir Cloudesley Shovell's fleet lay undisturbed on the seabed for over 250 years,[13] despite several salvage attempts in pursuit of the flagship's cargo of valuable coins, spoils of war from several battles, weapons, and personal effects.[25] In June 1967, the Royal Navy minesweeper HMS Puttenham, equipped with twelve divers under the command of Engineer-Lieutenant Roy Graham, sailed to the Isles of Scilly and dropped anchor off Gilstone Ledge, just to the south-east of Bishop Rock[26] and close to the Western Rocks. The year before, Graham and other specialists from the Naval Air Command Sub Aqua Club had dived in this area on a first attempt to find the Association. He recalled some years later: "The weather was so bad, all we achieved was the sight of a blur of seaweed, seals and white water as we were swept through the Gilstone Reef and fortunately out the other side."[13][27] On their second attempt in summer 1967, using the minesweeper and supported by the Royal Navy Auxiliary Service, Graham and his men finally managed to locate the remains of Admiral Shovell's flagship on the Gilstone Ledge.[27] Parts of the wreck are in 10 m (30 ft) while others can be found at between 30 m (90 ft) and 40 m (120 ft) as the sea floor falls away from the reef.[28] The divers first discovered a cannon, and on the third dive, silver and gold coins were spotted underneath that cannon.[27] The Ministry of Defence initially suppressed news of the discovery for fear of attracting treasure hunters, but word was soon out and excited huge national interest.[26] As the Isles of Scilly are traditionally administered as part of the Duchy of Cornwall, the Duke of Cornwall also has right of wreck on all ships wrecked on the Scilly archipelago. More than 2,000 coins and other artefacts were finally recovered from the wreck site and auctioned by Sotheby's in July 1969.[29] A further sale at Sotheby's in January 1970, by order of the Isles of Scilly Wrecks Receiver, made £10,175. Among the goods sold was Shovell's chamber pot for £270. A battered dining plate, which had been discovered during a dive in 1968, brought £2,100.[30] The rediscovery of the Association by naval divers and the finding of so many historical artefacts in her wreck also led to more government legislation, notably the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973, passed in an attempt to preserve British historic wreck sites as part of the maritime heritage.[16]

The wreck of Firebrand was discovered in 1982, and several items were recovered, including guns and anchors, a wooden nocturne (for determining the time at night), a bell and carved cherubs.[31]

Today photos of the original diving expedition are on display at the Old Wesleyan Chapel in St. Mary's, of the team leader Lt Graham and a naval doctor examining human bones from the wreck of the Association, alongside the ship's bell of the Firebrand with "1692" engraved on it, and many more artefacts.[26] In 2007, the three-hundredth anniversary of the disaster and its consequences were commemorated on the Isles of Scilly with a series of special events, organised by the Council of the Isles of Scilly in partnership with the local AONB office, English Heritage, the Isles of Scilly Museum and Natural England.[32]

Depiction in film

The disaster is featured at the start of the 2000 television drama Longitude, which is based on the book of the same name.[6]

See also

- List of disasters of the United Kingdom and preceding states

- List of shipwrecks of the Isles of Scilly

References

- ↑ The earliest reports of the disaster appeared in the Daily Courant, and were rather brief. The account for 1 November 1707 read: "an Account, that Sir Cloudsly Shovel with about 20 Sail of Men of War coming from the Streights, having made an Observation the 21st, lay the 22d from 12 to about 6 in the Afternoon; but the Weather being very hazy and rainy and Night coming on dark, the Wind being S.S.W, they Stearing E by N, supposing they had the Channel open, were some of them upon the Rocks to the Westward of Scilly before they were aware, about 8 a Clock at Night. Of the Association not a Man was sav’d ... The Captain and 24 Men of the Firebrand Fire-Shop were saved, as were also all the Crew of the Phoenix. ’Tis said the Rumney and Eagle, with their Crews, were lost with the Association." Cited in: Dunn, Richard. "Isles of Scilly Disaster - Part 2". Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ May, W.E. (1960). "The last voyage of Sir Clowdisley Shovell". Journal of Navigation. 13: 324–332. doi:10.1017/S0373463300033646.

- ↑ The list of ships, together with their captains, is given in Boyer, Abel (1708). History of the reign of Queen Anne, digested into annals. Year the sixth (1707). London: Margaret Coggan. pp. 241–245. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cooke, James Herbert (1 February 1883). "The Shipwreck of Sir Cloudesley Shovell on the Scilly Islands in 1707". London.

- 1 2 3 On 21 October, Shovell made an astronomical observation to determine his fleet's position, probably the first he had been able to take for many days. The next day, the weather worsened and another storm struck the fleet. Having obtained depth soundings at 90 fathoms, the admiral summoned the sailing masters of his ships on board HMS Association, and consulted them as to the fleet's actual position. All were of the opinion that they were in the latitude of Ushant and near the coast of France, except the sailing master of HMS Lenox, who judged they were nearer Scilly, and that three hours sail would bring them in sight of the isles. Shovell adopted the prevalent opinion and then detached Lenox, Valeur and Phoenix for Falmouth, Cornwall. These ships, following a north-easterly course, soon found themselves amongst the myriad rocks and islets to the south-west of the Isles of Scilly, where the Phoenix sustained so much damage that her captain and crew only saved the ship and themselves by running her ashore on the sands between Tresco and St Martin's. See James Herbert Cooke, The Shipwreck of Sir Cloudesley Shovell on the Scilly Islands in 1707, From Original and Contemporary Documents Hitherto Unpublished, Read at a Meeting of the Society of Antiquaries, London, 1 February 1883

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sobel, Dava (1998). Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of his Time. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 1-85702-571-7.

- ↑ "Tercentenary Commemorations of the 1707 Association Disaster". shipwrecks.uk.com.

- ↑ A photograph of the Outer Gilstone Rock, taken from www.shipwrecks.uk.com and retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ↑ For more detail on the wreck and its salvage in the 20th century, see McBride, Peter and Larn, Richard (1999) Admiral Shovell's treasure; ISBN 0-9523971-3-7 (hardback) ISBN 0-9523971-2-9 (paperback). This includes much detailed information, such as a Shovell family tree.

- 1 2 "Sir Clowdisley Shovell". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mitchell, Peter (4 July 2007). "Sir Clowdisley Shovell and The Association". Submerged.

- ↑ "HMS Romney (+1707)". wrecksite.eu.

- 1 2 3 4 "HMS Association (+1707)". wrecksite.eu.

- 1 2 3 "The legacy of Sir Cloudsley Shovel". Kent History Forum.

- ↑ Abbott, Bill (2005). "Sir Cloudesley Shovell". Britannia. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- 1 2 "HMS Association Tricentenary Leaflet". shipwrecks.uk.com.

- ↑ A photograph by Frank W.Gibson of Admiral Shovell's temporary grave in Porthellick Cove.

- 1 2 Damer Powell, J. W. (1957). "Notes: The Wreck of Sir Cloudesley Shovell". The Mariner's Mirror. 43 (4): 333–336. doi:10.1080/00253359.1957.10658366.

- 1 2 Pickwell, J. G. (1973). "Improbable Legends surrounding Sir Clowdisley Shovell". The Mariner's Mirror. 59 (2): 221–223. doi:10.1080/00253359.1973.10657899.

- ↑ Dunn, Richard (27 October 2014). "The 1707 Isles of Scilly Disaster – Part 2". Royal Museums Greenwich.

- ↑ May, W. E. (1953). "Naval Compasses in 1707". Journal of Navigation. 6 (4): 405–9. doi:10.1017/S0373463300027879.

- ↑ McBride, Peter; Larn, Richard (1999). Admiral Shovell's Treasure. pp. 50–52. ISBN 0-9523971-3-7.

- ↑ May, William Edward (1973). A History of Marine Navigation. Henley-on-Thames: G. T. Foulis. ISBN 0-85429-143-1.

- ↑ "HMS Association". ukdiving.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 Farrell, Nigel (2008). An Island Parish. A Summer on Scilly. London: Headline. pp. 205–207. ISBN 978-0-7553-1764-6.

- 1 2 3 "The Wreck of the Association - The Inside Story". Scilly News. 2 December 2005.

- ↑ "Wreck of the fleet and treasures of the deep" (PDF). The Islander (3). Autumn/Winter 2007. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "The HMS Association Treasure Wreck, Scilly Isles". Metal Detecting UK.

- ↑ Eastern Daily Press (EDP2 Feature p. 5) on Friday, 29 January 2010.

- ↑ "News". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 11 (3): 254–257. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.1982.tb00088.x.

- ↑ Council of the Scilly Isles website.

Further reading

- Roland Morris, Island Treasure: The Search for Sir Cloudesley Shovell's Flagship 'Association' , Hutchinson 1969 (ISBN 0090894006)

- Peter McBride, Richard Larn, Admiral Shovell's Treasure and Shipwreck in the Isles of Scilly, Shipwreck & Marine 1999 (ISBN 0952397129)

- Richard Larn (ed.), Poor England has Lost so Many Men, Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2007 (ISBN 0952397161)

- Mark Nicholls, Norfolk Maritime Heroes and Legends, Cromer, Norfolk: Poppyland 2008, pages 25–30 (ISBN 978-0-946148-85-1)

External links

- Scilly History – HMS Association

- El Desastre Naval de las Islas Sorlingas de 1707 (Spanish)