17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency

| 17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

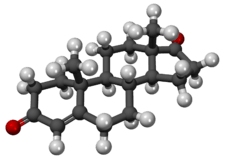

| Biochemical effects of 17β-hydroxysteroid deficiency-3 in testosterone biosynthesis. Typically levels of androstenedione are significantly increased, whilst testosterone levels are decreased, leading to male undervirilization. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | E29.1 |

| OMIM | 264300 |

| DiseasesDB | 32638 |

| Orphanet | 752 |

17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency is a rare disorder of sexual development, or intersex condition, affecting testosterone biosynthesis by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III (17β-HSD III),[1][2] which can produce impaired virilization (historically termed male pseudohermaphroditism) of genetically male infants and children and excessive virilization of female adults. It is an autosomal recessive condition and is one of the few disorders of sexual development that can affect the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of both males and females.

Signs and symptoms

17-β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency is clinically characterized by either ambiguous external genitalia or complete female external genitalia at birth; as a consequence of impaired male sexual differentiation in 46,XY individuals, as well as:[3][1][4]

- Hypothyroidism

- Cryptorchidism

- Infertility

- Abnormality of metabolism

Genetics

Genetically speaking, 17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency is caused by mutations found in the 17β-HSD III (17BHSD3) gene.17β-HSD III deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder.[5][6]

Biochemistry mechanism

A deficiency in the HSD17B3 gene is characterized biochemically by decreased levels of testosterone and increased levels of androstenedione as a result of the defect in conversion of androstenedione into testosterone, this leads to clinically important higher ratio of androstenedione to testosterone[7][5][8]

Androstenedione is produced in the testis, as well as the adrenal cortex. Androstenedione is created from dehydroepiandrosterone (or 17-hydroxyprogesterone).[9]

Diagnosis

In terms of the diagnosis of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency the following should be taken into account:[10][2]

- Delta(4)-A to T ratio (unusually increased)

- Thyroid dyshormonogenesis

- Genetic testing

Management

The 2006 Consensus statement on the management of intersex disorders states that individuals with 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency have an intermediate risk of germ cell malignancy, at 28%, recommending that gonads be monitored.[11] A 2010 review put the risk of germ cell tumors at 17%.[12]

The management of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency can consist, according to one source, of the elimination of gonads prior to puberty, in turn halting masculinization.[2]

Hewitt and Warne state that, children with 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency who are raised as girls often later identify as male, describing a "well known, spontaneous change of gender identity from female to male" that "occurs after the onset of puberty."[13] A 2005 systematic review of gender role change identified the rate of gender role change as occurring in 39–64% of individuals with 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III deficiency raised as girls.[14]

Society and culture

Modification of children's sex characteristics to meet social and medical norms is strongly contested, with numerous statements by civil society organizations and human rights institutions condemning such interventions, including describing them as "harmful practices".[15][16][17]

Re: Carla (Medical procedure)

A 2016 case before the Family Court of Australia[18] was widely reported in national,[19][20][21] and international media.[22] The judge ruled that parents were able to authorize the sterilization of their 5-year old child. The child had previously been subjected to intersex medical interventions including a clitorectomy and labiaplasty, without requiring Court oversight - these were described by the judge as having "enhanced the appearance of her female genitalia".[18] Organisation Intersex International Australia found this "disturbing", and stated that the case was reliant on gender stereotyping and failed to take account of data on cancer risks.[23]

See also

- Inborn errors of steroid metabolism

- Disorders of sexual development

- Intersex

- 17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (III)

- Sex hormone (androgen/estrogen)

References

- 1 2 Reference, Genetics Home. "17-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3 deficiency". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- 1 2 3 "OMIM Entry - # 264300 - 17-BETA HYDROXYSTEROID DEHYDROGENASE III DEFICIENCY". omim.org. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ "17-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3 deficiency | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ "46, XY disorders of sexual development | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- 1 2 Reference, Genetics Home. "HSD17B3 gene". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: 46,XY disorder of sex development due to 17 beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3 deficiency". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ↑ "HSD17B3 hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 3 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - * 605573 - 17-BETA HYDROXYSTEROID DEHYDROGENASE III; HSD17B3". omim.org. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ↑ Pubchem. "androstenedione | C19H26O2 - PubChem". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ↑ "Testosterone 17-beta-dehydrogenase deficiency - Conditions - GTR - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ↑ Lee P. A.; Houk C. P.; Ahmed S. F.; Hughes I. A. (2006). "Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders". Pediatrics. 118 (2): e488–500. PMID 16882788. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0738.

- ↑ Pleskacova, J.; Hersmus, R.; Oosterhuis, J.W.; Setyawati, B.A.; Faradz, S.M.; Cools, M.; Wolffenbuttel, K.P.; Lebl, J.; Drop, S.L.; Looijenga, L.H. (2010). "Tumor Risk in Disorders of Sex Development". Sexual Development. 4 (4-5): 259–269. ISSN 1661-5433. doi:10.1159/000314536.

- ↑ Hewitt, Jacqueline K.; Warne, Garry L. (February 2009). "Management of disorders of sex development". Pediatric Health. 3 (1): 51–65. ISSN 1745-5111. doi:10.2217/17455111.3.1.51.

- ↑ Cohen-Kettenis, Peggy T. (August 2005). "Gender Change in 46,XY Persons with 5α-Reductase-2 Deficiency and 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase-3 Deficiency". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 34 (4): 399–410. ISSN 0004-0002. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-4339-4.

- ↑ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (October 24, 2016). "Intersex Awareness Day – Wednesday 26 October. End violence and harmful medical practices on intersex children and adults, UN and regional experts urge".

- ↑ Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, February 2013.

- ↑ Council of Europe; Commissioner for Human Rights (April 2015), Human rights and intersex people, Issue Paper

- 1 2 Re: Carla (Medical procedure), FamCA 7 (Family Court of Australia January 20, 2016).

- ↑ Overington, Caroline (December 7, 2016). "Family Court backs parents on removal of gonads from intersex child". The Australian.

- ↑ Overington, Caroline (December 8, 2016). "Carla’s case ignites firestorm among intersex community on need for surgery". The Australian.

- ↑ Copland, Simon (December 15, 2016). "The medical community's approach to intersex people is still primarily focused on 'normalising' surgeries". SBS. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ↑ Dunlop, Greg (December 7, 2016). "Australian court approves intersex child's surgery". BBC News.

- ↑ Carpenter, Morgan (December 8, 2016). "The Family Court case Re: Carla (Medical procedure) [2016] FamCA 7". Organisation Intersex International Australia. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

Further reading

- Bissonnette, Bruno (2006). Syndromes: Rapid Recognition and Perioperative Implications. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 9780071354554. Retrieved 11 March 2017.