Migalastat

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Galafold |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth (capsules) |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 75% |

| Protein binding | None |

| Metabolites | O-glucuronides (<15%) |

| Biological half-life | 3–5 hours (single dose) |

| Excretion | Urine (77%), feces (20%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | DDIG, AT1001 |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H13NO4 |

| Molar mass | 163.17 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Migalastat (INN/USAN), or 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin, trade name Galafold (formerly known as Amigal) is a drug for the treatment of Fabry disease,[1] a rare genetic disorder. It was developed by Amicus Therapeutics. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) assigned it orphan drug status in 2004,[2] and the European Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) followed in 2006. The European Commission approved the drug in May 2016.[3]

Medical uses

Migalastat is used for the long-term treatment of Fabry disease in adults and adolescents aged 16 or older with an amenable mutation of the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (α-GalA). An "amenable" mutation is one that leads to misfolding of the enzyme, but otherwise would not significantly impair its function.[4][5]

Based on an in vitro test, Amicus Therapeutics has published a list of 269 amenable and nearly 600 non-amenable mutations. About 35 to 50% of Fabry patients have an amenable mutation.[4][5][6]

Adverse effects

No serious adverse effects have been found in small studies over the course of four years.[7] The most common side effect in clinical trials was headache (in about 10% of patients). Less common side effects (between 1 and 10% of patients) included unspecific symptoms such as dizziness, fatigue, and nausea, but also depression. Possible rare side effects could not be assessed because of the low number of patients in studies.[4][5]

Interactions

When combined with intravenous agalsidase alfa or beta, which are recombinant versions of the enzyme α-GalA, migalastat increases tissue concentrations of functional α-GalA compared to agalsidase given alone. This is an expected and desired effect.[1]

Migalastat does not inhibit or induce cytochrome P450 liver enzymes or transporter proteins and is therefore expected to have a low potential for interactions with other drugs.[4]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Fabry disease is a genetic disorder caused by various mutations of the enzyme α-GalA, which is responsible for breaking down the ganglioside globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), among other glycolipids and glycoproteins. Some of these mutations result in misfolding of α-GalA, which subsequently fails protein quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum and is decomposed. Lack of functional α-GalA leads to accumulation of Gb3 in blood vessels and other tissues, with a wide range of symptoms including kidney, heart, and skin problems. Available treatments are substitution therapies with recombinant α-GalA (agalsidase), which has to be applied intravenously.[5][7]

Migalastat is a potent, orally available inhibitor of α-GalA (IC50: 4 μM).[8] When binding to faulty α-GalA, it shifts the folding behaviour towards the proper conformation, resulting in a functional enzyme provided the mutation is amenable.[5][7] Molecules with this type of mechanism are called pharmacological chaperones.[7]

When the enzyme reaches its destination, the lysosome, migalastat dissociates because of the low pH and the relative abundance of Gb3 and other substrates, leaving α-GalA free to fulfill its function.[9] Depending on the mutation, the EC50 is between 0.8 µM and over 1 mM in cellular models.[10]

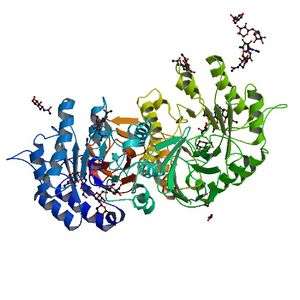

The enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (α-GalA)

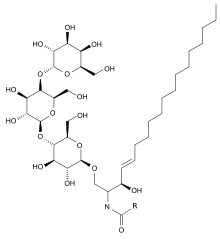

The enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (α-GalA) Globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), a substrate of α-GalA, has a terminal D-galactose structurally similar to migalastat.[1]

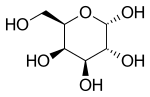

Globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), a substrate of α-GalA, has a terminal D-galactose structurally similar to migalastat.[1] Migalastat ("top" view)

Migalastat ("top" view)

Pharmacokinetics

Migalastat is almost completely absorbed from the gut, but taking the drug together with food decreases absorption by about 40%. Total bioavailability is about 75% when taken without food. The substance is not bound to blood plasma proteins.[4]

Only a small fraction of a migalastat dose is metabolized, mainly to three dehydrogenated O-glucuronides (4% of the dose) and a number of unspecified metabolites (10%). The drug is mainly eliminated via the urine (77%) and to a smaller extent via the faeces (20%). Practically all of the metabolites are excreted in the urine. Elimination half-life is three to five hours after a single dose.[4]

Chemistry

Migalastat is used in form of the hydrochloride, which is a white crystalline solid and is soluble in water (≥1 mg/mL).[11] The molecule has four asymmetric carbon atoms with the same stereochemistry as the sugar D-galactose,[1] but is missing the first hydroxyl group. It has a nitrogen atom in the ring instead of an oxygen, which makes it an iminosugar.[12]

The structure is formally derived from nojirimycin.

History

Migalastat was isolated as a fermentation product of the bacterium Streptomyces lydicus (strain PA-5726) in 1988 and called 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin.[12][13] In 2004, it was designated orphan drug status by the US FDA for the treatment of Fabry disease,[2] and in 2006 the European CHMP did likewise.[14] The sponsorship for the drug was transferred several times over the following years: from Amicus Therapeutics to Shire Pharmaceuticals in 2008, back to Amicus in 2010, to Glaxo in 2011, and again to Amicus in 2014.[15]

Two phase III clinical trials with a total of about 110 patients were conducted between 2009 and 2015, one double-blind comparing the drug to placebo, and one comparing it to recombinant α-GalA without blinding. Migalastat stabilised heart and kidney function over the 30-months period of these trials.[5][16][17]

In September 2015, the developer announced that they would submit a new drug application for migalastat to the FDA by the end of 2015.[18] The CHMP recommended approval in April 2016, following the results of the two phase III trials,[14] and the drug was approved in the European Union in May 2016.[3] Germany is the first country where migalastat was launched.[3]

See also

- Miglustat, a drug for the treatment of Gaucher disease, with a similar structure

- 1-Deoxynojirimycin, a stereoisomer of migalastat

References

- 1 2 3 4 Warnock, D. G.; Bichet, D. G.; Holida, M; Goker-Alpan, O; Nicholls, K; Thomas, M; Eyskens, F; Shankar, S; Adera, M; Sitaraman, S; Khanna, R; Flanagan, J. J.; Wustman, B. A.; Barth, J; Barlow, C; Valenzano, K. J.; Lockhart, D. J.; Boudes, P; Johnson, F. K. (2015). "Oral Migalastat HCl Leads to Greater Systemic Exposure and Tissue Levels of Active α-Galactosidase a in Fabry Patients when Co-Administered with Infused Agalsidase". PLoS ONE. 10 (8): e0134341. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1034341W. PMC 4529213

. PMID 26252393. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134341.

. PMID 26252393. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134341. - 1 2 "List of Orphan Products Designations". US FDA. 28 April 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Amicus Therapeutics Announces European Commission Approval for Galafold (Migalastat) in Patients with Fabry Disease in European Union". GlobeNewswire. 31 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Summary of Product Characteristics for Galafold" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 H. Spreitzer (23 April 2016). "Neue Wirkstoffe – Migalastat". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (9/2016): 12.

- ↑ "Galafold Amenability Table". Amicus Therapeutics. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Germain, Dominique P; Giugliani, Roberto; Hughes, Derralynn A; Mehta, Atul; Nicholls, Kathy; Barisoni, Laura; Jennette, Charles J; Bragat, Alexander; Castelli, Jeff; Sitaraman, Sheela; Lockhart, David J; Boudes, Pol F (2012). "Safety and pharmacodynamic effects of a pharmacological chaperone on α-galactosidase A activity and globotriaosylceramide clearance in Fabry disease: report from two phase 2 clinical studies". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 7: 91. PMC 3527132

. PMID 23176611. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-91.

. PMID 23176611. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-91. - ↑ Sánchez-Fernández, Elena M.; García Fernández, José M.; Mellet, Carmen Ortiz (2016). "Glycomimetic-based pharmacological chaperones for lysosomal storage disorders: lessons from Gaucher, GM1-gangliosidosis and Fabry diseases". Chem. Commun. 52 (32): 5497. doi:10.1039/C6CC01564F.

- ↑ Yam, G. H.; Bosshard, N; Zuber, C; Steinmann, B; Roth, J (2006). "Pharmacological chaperone corrects lysosomal storage in Fabry disease caused by trafficking-incompetent variants". AJP: Cell Physiology. 290 (4): C1076–82. PMID 16531566. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00426.2005.

- ↑ Benjamin, E. R.; Flanagan, J. J.; Schilling, A; Chang, H. H.; Agarwal, L; Katz, E; Wu, X; Pine, C; Wustman, B; Desnick, R. J.; Lockhart, D. J.; Valenzano, K. J. (2009). "The pharmacological chaperone 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin increases alpha-galactosidase A levels in Fabry patient cell lines". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 32 (3): 424–40. PMID 19387866. doi:10.1007/s10545-009-1077-0.

- ↑ Sigma-Aldrich Co., product no. D9641.

- 1 2 Asano, N (2007). "Naturally occurring iminosugars and related alkaloids: structure, activity and applications". In Compain, P; Martin, OR. Iminosugars: from synthesis to therapeutic applications. Wiley and Sons. p. 17. ISBN 0-470-03391-6.

- ↑ Miyake, Y; Ebata, M (1988). "The structures of a β-galactosidase inhibitor, Galactostatin, and its derivatives". Agric Biol Chem. 52: 661–666. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.52.661.

- 1 2 "Galafold". European Medicines Agency. 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Public summary of opinion on orphan designation". European Medicines Agency. 29 April 2014.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00925301 for "Study of the Effects of Oral AT1001 (Migalastat Hydrochloride) in Patients With Fabry Disease" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT01218659 for "Study to Compare the Efficacy and Safety of Oral AT1001 and Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Patients With Fabry Disease" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ "Amicus Therapeutics Plans to Submit NDA for Migalastat for Fabry Disease Following Positive Pre-NDA Meeting With FDA". Drugs.com. 15 September 2015.